The United States lost its first nuclear weapon exactly 75 years ago when a Convair B-36 Peacemaker jettisoned a single freefall nuclear bomb before crashing in northwestern British Columbia, Canada. This was the first of at least 32 known U.S. nuclear weapon accidents, known as Broken Arrows, which are defined as the accidental launching, firing, detonating, theft, or loss of a weapon. None of these have occurred since the Cold War, but their legacy remains a stark reminder of the enormously high stakes faced by atomic warfighters in all their forms.

Just before midnight on Feb. 13, 1950, a B-36B from Strategic Air Command’s 7th Bombardment Wing-Heavy, opened its bomb bay doors at around 8,000 feet, around 55 miles northwest of Bella Bella, on the north coast of British Columbia. A single Mk 4 nuclear bomb plummeted into the Pacific Ocean; there was a bright flash on impact, followed by a sound and shockwave.

The detonation was caused by the bomb’s high-explosive material, with the fissile core having been removed and replaced with a lead practice core of the same weight. Otherwise, with a yield of up to 31 kilotons, it would have had roughly twice the destructive power of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

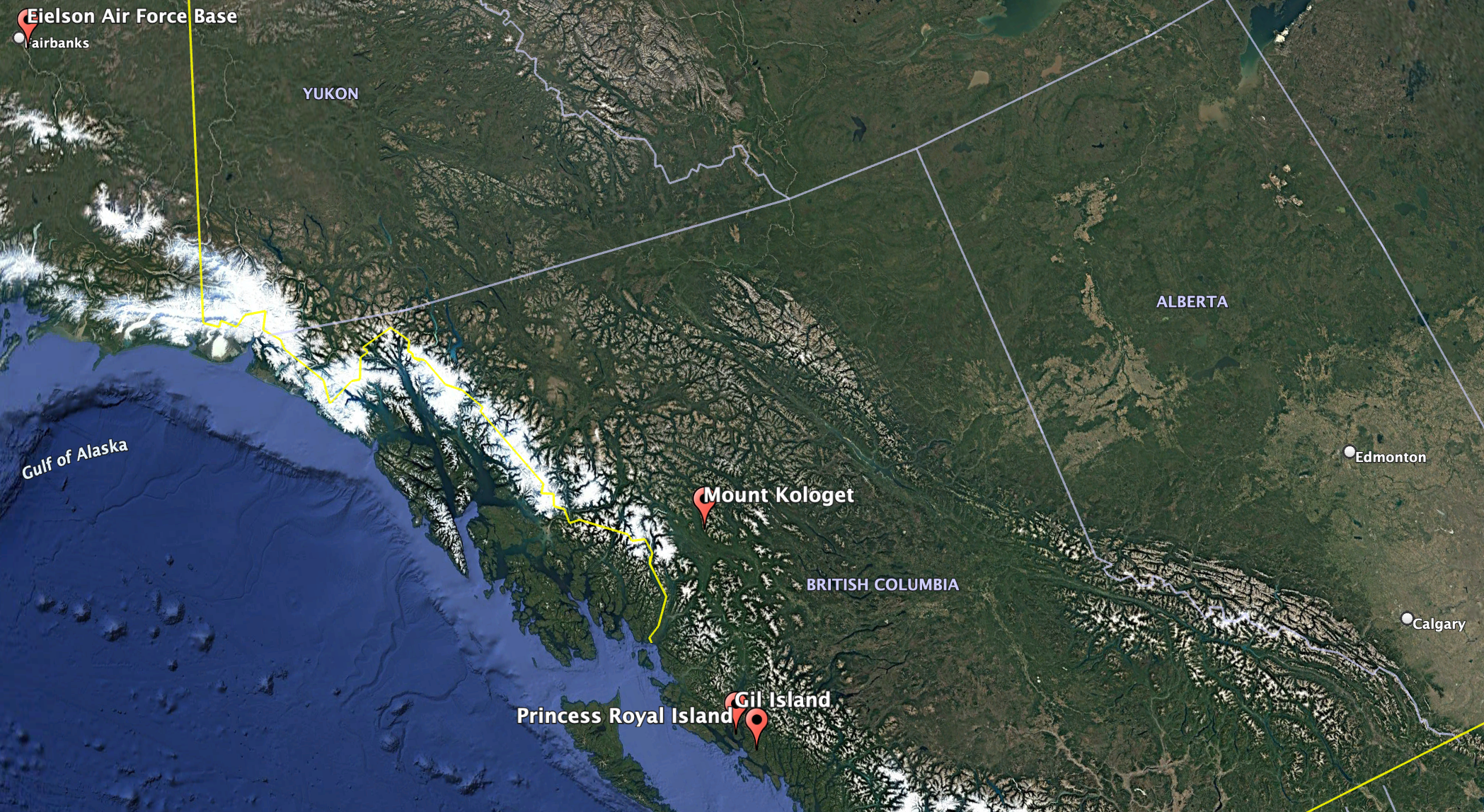

Led by pilot Capt. Harold Barry, the crew of the B-36 took the decision to drop the unarmed bomb after encountering serious mechanical problems in the course of a training mission. This had involved a simulated combat profile flown between Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska and Carswell Air Force Base in Texas (the latter was the home station of the 7th Bombardment Wing, Heavy). The simulated target would have been San Francisco, standing in for a Soviet or Chinese city of comparable size.

At the time, the B-36 was very much the cutting-edge of Strategic Air Command — the first truly intercontinental U.S. bomber, the airframe involved in the incident was also very new, with only 186 hours of flying before its loss.

Soon after taking off, the bomber had run into trouble.

After entering bad weather, ice began to form on the exterior of the aircraft. In an effort to maintain the required altitude, the crew powered up the engines. Around six hours into the training mission and at an altitude of around 12,000 feet, three of the engines caught fire and had to be shut down.

The bomber was now flying on its remaining three Pratt & Whitney Wasp Major radial engines — the B-model was yet to receive the four additional J47 turbojet engines, two each in two underwing pods, which appeared on later Peacemakers and gave a much-needed performance boost.

Despite the emergency power settings on the three engines, the aircraft was now losing altitude. When it became apparent that level flight could no longer be maintained, the decision was made to abandon the aircraft.

First, and following Air Force protocol of the time, the Mk 4 nuclear bomb had to be jettisoned, its fuze having been set to detonate at around 4,600 feet — once again, there was no nuclear material in the weapon. At this time, U.S. freefall bombs were designed to have their fissile cores inserted during flight, a safeguard that was deemed necessary for these first-generation strategic weapons. Only with a presidential decision would a bomber take off with the fissile core onboard.

Barry later told an Air Force board of inquiry, in a testimony later published by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists:

“We were losing altitude quite rapidly in excess of 500 feet a minute, and I asked the radar operator to give me a heading to take me out over water. We kept our rapid rate of descent, and we got out over the water just about 9,000 feet, and the copilot hit the salvo switch, and at first, nothing happened, so he hit it again and this time it opened. The radar operator gave me a heading to take me back over land, the engineer gave me emergency power to try to hold our altitude. We still descended quite rapidly, and by the time we got over land, we were at 5,000 feet. So, I rang the alarm bell and told them to leave.”

Barry then set the aircraft’s course to fly southwest for an ocean crash. The 17-man crew bailed out over Princess Royal Island.

There was a huge rescue effort to try and recover the crew and sensitive equipment from the aircraft. In all, more than 40 U.S. and Canadian aircraft were involved.

A search southwest of the bailout point found no sign of the bomber, which was, at this point, thought to have come down in the sea.

Of the crew, five were never recovered. It’s presumed they came down in the water between Gil and Princess Royal islands. In freezing conditions, and without exposure suits, they wouldn’t have survived long; furthermore, not all the crew had inflatable life jackets.

As for the B-36, the wreckage was eventually found in 1953, on the side of Mount Kologet on Vancouver Island, around 220 miles north of where the crew had bailed out. The bomber had been uncovered during a separate Royal Canadian Air Force search for a missing oil prospector.

With concerns that sensitive equipment from the bomber might find its way into the Soviets’ hands, the U.S. Air Force sent a recovery team, but they were initially unable to access the mountainous crash site. Two follow-up missions were sent and, finally, in 1954, a small demolition team managed to get to the crash site and secure or destroy classified parts of the bomber.

One of the missing crewmembers was the atomic weaponeer, Capt. Theodore Schreier. With no confirmation that he bailed out, this led to some speculation that he may have decided to stay onboard the stricken aircraft. This, in turn, raised questions about whether the bomb had also remained on board, with Schreier attempting to nurse the aircraft back to Alaska.

However, all evidence points to the crew having successfully fuzed the bomb to explode, dropping it out of the bomb bay, and watching it detonate above the water. A more recent investigation of the crash site suggests the same, with the bomb shackle showing no evidence that the plane crashed with a weapon onboard.

As the site of the first Broken Arrow, the location of the crash has been visited periodically by investigators in the years since the accident. Also, trophy hunters have stripped much of what was left of the bomber for artifacts. Now, with the availability of helicopters, and with less snow on the ground, it has become much easier to reach the crash site.

During a 2003 visit, an investigation team found the aft crew compartment, the rear bomb bay, and one section of the outer wing, as the only significant intact parts, with the wreckage otherwise mostly consisting of the tiny pieces left after the demolition team did their work.

When the B-36 and its nuclear cargo were lost on Feb. 13, 1950, the United States and the Soviet Union were only just embarking on the Cold War and the tense nuclear standoff that would follow for decades beyond. Indeed, at the time of this incident, the United States still enjoyed a huge advantage over its adversary in terms of nuclear capability, with around 235 fully functional atomic bombs compared to perhaps two in the Soviet Union.

As the Soviets matched that gap, and the nuclear stockpiles in East and West continued to grow, the demands of maintaining and operating weapons safely became ever greater. Broken Arrow incidents have led to the confirmed loss of six nuclear weapons that were never recovered, but each incident has also served as a stark learning process, leading to revisions in how U.S. nuclear weapons are stored and operated.

In the Canadian context, another Mk 4 nuclear bomb was jettisoned over Quebec later in 1950, after a Strategic Air Command B-50 suffered engine trouble, but subsequently landed safely. In that incident, the high explosive detonated, and around 100 pounds of uranium — used for the bomb’s tamper, the dense metal used to hold the core together, rather than the core itself — were scattered over the nearby area.

As for the U.S. Air Force, the service’s nuclear-armed bombers would soon be airborne at all times, in an alert posture known as Operation Chrome Dome, which ran from 1960 to 1968. Several high-profile nuclear accidents, including the accidental release of nuclear weapons on foreign territory, saw Chrome Dome replaced.

Between 1969 and 1991, the Air Force instead kept B-52 bombers armed with nuclear weapons on alert at all times to try to ensure that they could rapidly get airborne and escape any potential first strike on their operating bases and then be available to retaliate. You can read more about this doctrine in this past War Zone piece.

A Broken Arrow event of the kind that happened in February 1950 might seem unthinkable today, but there have been some concerning nuclear incidents, even in more recent years.

Notably, in 2007, Air Force personnel mistakenly loaded six AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missiles, each with a W80-1 variable-yield nuclear warhead, with a maximum yield estimated at 150 kilotons, onto a B-52 at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota.

The Stratofortress then flew with these weapons on board, unknown to the crew, to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. In the end, the aircraft was armed with live nuclear weapons for a total of 36 hours before personnel uncovered the error and instituted appropriate security and safety precautions at Barksdale.

Ultimately, human beings are fallible, as are the systems they have designed to control nuclear weapons. While the Air Force may not have been involved in a Broken Arrow incident since 1980 — and the last one involved an ICBM, rather than a crewed bomber — the potential hazards of the deadly business of nuclear warfighting remain just as relevant today.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com