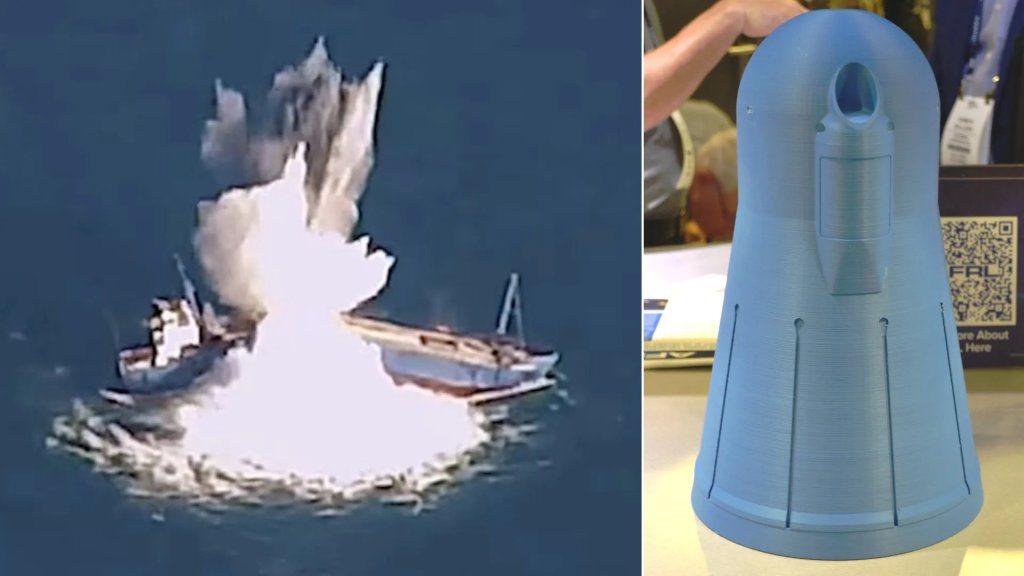

A relatively low-cost cruise missile that the U.S. Air Force is now developing could transform into an air-launched counter-drone weapon. The service previously disclosed that it is also eyeing an anti-ship version of the ostensibly air-to-ground Extended Range Attack Munition (ERAM), work on which first started primarily to meet the needs of the Ukrainian armed forces.

The Air Force has confirmed to TWZ that a “capability” called the Fixed Wing, Air Launched, Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Systems Ordnance (FALCO) is among multiple subsystems that could be added to future versions of ERAM. Earlier this month, the Stand-In Strike Division of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center’s Armament Directorate, based at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida, had put out a contracting notice regarding ERAM that named FALCO by acronym only and provided no further details. That same notice mentioned the seeker developed under the separate Quicksink anti-ship munition program, as well as two additional capabilities called Marshall Deck of Cards (Marshall DoC) and Shepherd, which we have now also been told are classified.

“As for ERAM, the current state of the program is we are in Phase 1 of a 3 Phased approach to weapon development, test, production, and employment,” an Air Force spokesperson at Eglin told TWZ. “The RFI [request for information contracting notice] was released as a mechanism to produce market research to procure sub-systems and ornaments from BAE [Systems] for follow-on ERAM variants, in addition to being useful for other weapons.”

“FALCO is a counter-UAS capability,” the spokesperson added. “The RFI market research should allow the program office to purchase test assets and or production variants in support of program objectives.”

What FALCO consists of in its current form and what it might take to adapt it to ERAM is unknown. For use in the anti-air role, active and/or passive seekers, or some form of command guidance, would be required. TWZ previously reached out to BAE Systems for more information about FALCO and the other subsystems named in the RFI, and we have now done so again.

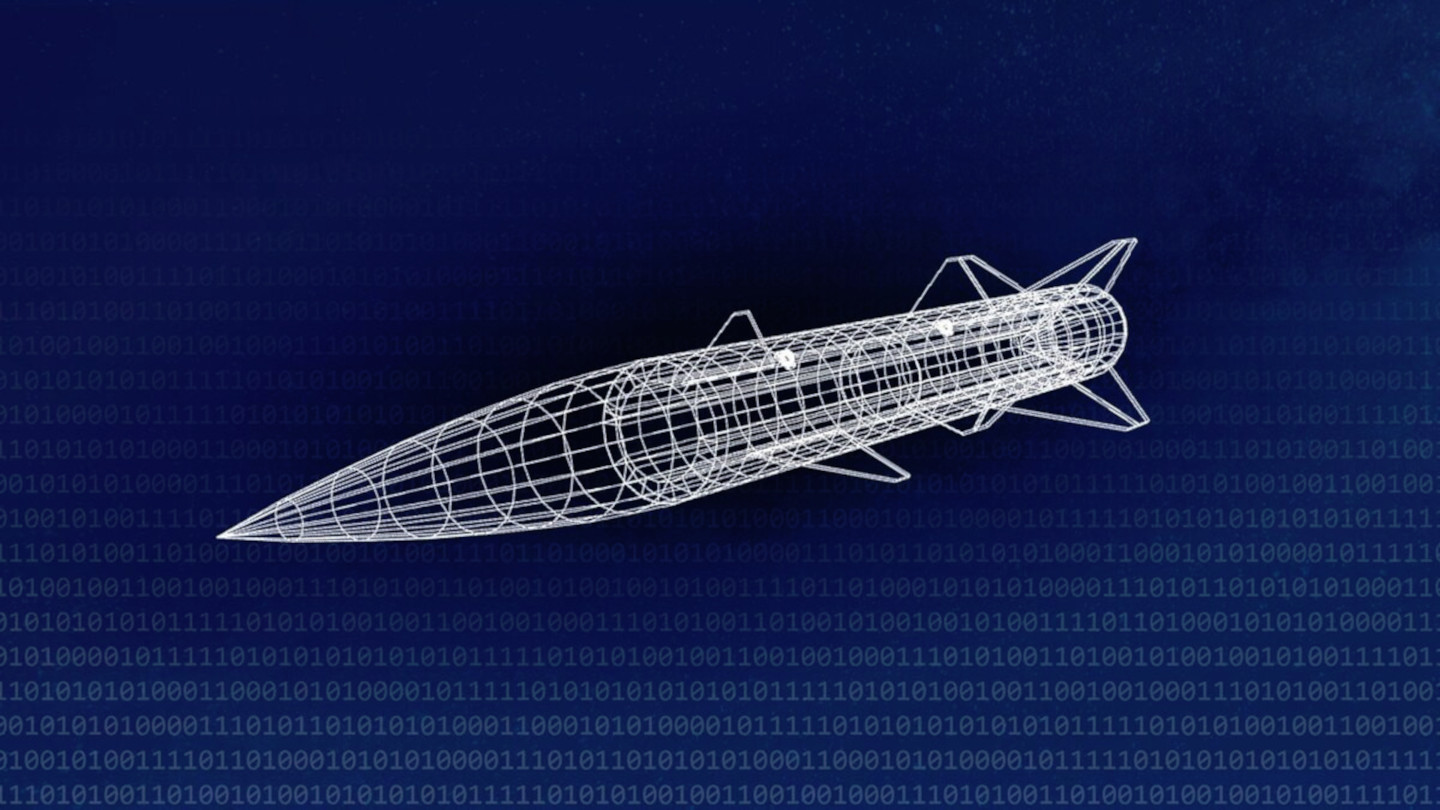

Details about the core ERAM design also remain limited. As we wrote previously:

“In a previous contracting notice, the Air Force laid out requirements for a 500-pound-class precision munition with a range of up to 250 miles while flying at a speed of at least Mach 0.6. The weapon also has to use an INS-based guidance package ‘capable of operating in a GPS degraded environment’ and that offers ‘terminal Accuracy’ of ‘CEP 50 w/in 10m’ (the ability to impact within 10 meters, or around 33 feet, of a specified point at least 50 percent of the time) in ‘both in non-EMI (Electromagnetic Interference) and high EMI environments (includes GPS degraded).'”

The Air Force has a clear interest in new and lower-cost air-to-air capabilities, especially for use against drones and subsonic cruise missiles. TWZ exclusively confirmed just this week that the service’s F-16 Viper fighters have been shooting down drones launched by Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen using laser-guided 70mm Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II) rockets. APKWS II was originally developed as a cheaper air-to-ground precision munition. In 2019, the Air Force announced it had successfully demonstrated the ability to use rockets in the air-to-air role.

Using APKWS II as an air-to-air weapon “is a lower-cost option compared to the AIM-9X. That lower cost is one of the benefits of using it,” a U.S. military official told TWZ.

A current generation Block II subvariant of the AIM-9X Sidewinder has a unit price of just under $420,000, according to Pentagon budget documents. The price of a single AIM-120 Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM), which U.S. forces have also been employing in operations against the Houthis, is more than $1 million. In contrast, an APKWS II rocket’s unit cost, depending on how it is configured, is in the low tens of thousands of dollars.

While we don’t know what unit cost the Air Force is targeting for ERAM, other broadly similar efforts in progress elsewhere within the U.S. military and private industry have been eyeing price points around $300,000.

Given what is known about the baseline ERAM design, an air-to-air version would likely be limited to employment against lower-performance and less reactive targets flying along steady flight paths, as is also the case with APKWS II in this role. At the same time, with a range of 250 miles, an air-to-air interceptor version of the ERAM would have dramatically greater reach than the laser-guided rockets, or even traditional medium-range air-to-air missiles like the AIM-120. Networked kill webs feeding in targeting data from offboard sources would be essential for prosecuting engagements at these ranges.

A 250-mile range would also translate to endurance for an ERAM interceptor to potentially function as a loitering air-to-air weapon. Such a munition could be fired into forward areas where drones and other slower and less maneuverable targets are known to be or expected to pass through. Depending on its guidance package, it might be able to then spot and attempt to intercept those threats automatically. This, in turn, would present complications for enemy forces, as well as an additional stand-off layer of defense against incoming threats.

The U.S. military already has surface-to-air interceptors with degrees of loitering capability in service in the form of Raytheon’s Coyote Block 2 and Anduril’s Roadrunner-M, the latter of which is also fully reusable if it is not expended. Their performance differs substantially from what an air-to-air version of ERAM could offer. Loitering air defense interceptors are emerging elsewhere globally, as well.

Whatever its exact capabilities, an air-to-air version of ERAM could still be a valuable addition to a mix of future air-to-air capabilities, which might also be adaptable for launch from launchers on ground-based or maritime platforms. As the Eglin spokesperson highlighted, FALCO, or technologies used in it, could find their way onto other weapon systems, as well. All of this aligns with broader U.S. military-wide efforts to find ways to accelerate not just the development of new munitions and other capabilities, but also their production at useful scales.

Having additional lower-cost munition options in the mix, in general, could also help alleviate strains on stockpiles of more exquisite munitions. Operations against, the Houthis, as well as in the defense of Israel, since October 2023, together with recent obligations to allies and partners, especially Ukraine, have prompted serious criticisms and concerns about the adequacy of key U.S. munitions inventories and the ability to replenish them, especially in a future high-fight, such as one in the Pacific against China.

The Air Force is hardly alone in facing these realities and using a highly modular ERAM design to develop a diverse family of munitions capable of engaging targets on land, at sea, and in the air, could easily be of interest elsewhere within the U.S. military, as well as outside of the United States. As noted, the ERAM program has been primarily focused from the start on delivering a valuable new precision air-to-ground munition capability to Ukraine’s military, which also regularly faces down waves of incoming Russian kamikaze drones and cruise missiles.

Overall, the details that continue to emerge about ERAM, including now the possibility of using FALCO to turn it into an air-to-air weapon, steadily point to a program with the potential to have broad ramifications for U.S. military ‘weaponeering’ efforts going forward.

Contact the author: joe@twz.com