By 2050, the U.S. Air Force will face the challenge of missiles that can target its aircraft at ranges as great as 1,000 miles — a huge advance in anti-access capabilities compared to the distances air defense missiles can reach today. This is one of the standout predictions from a new report to Congress by the Department of the Air Force, which aims to present a vision of what the Air Force and Space Force should look like by the middle of the century.

The understanding that air defense missiles will, by 2050, be able to hit their targets at such long ranges is presented in the report’s assessment of how wars in the air will likely look very different at that point.

“Control of the air will still be critical to military success, but how, when, and where it will be achieved are all subject to change,” the report notes. “Two fundamental developments make this necessary. The first is the vulnerability of forward-located fixed bases (and, to some extent, even remote air bases) to attack by precision missiles. The second is the extension of counter-air weapons engagement zones to unprecedented, almost unlimited, ranges.”

Specifically, by 2050, Air Force operations will be expected to be challenged by counter-air weapons “with ranges out to over 1,000 miles and supported by space-based sensors.” In particular, such long-reaching weapons will threaten “aircraft, such as tankers, that have traditionally operated with impunity.”

For some time now, the Air Force has been looking to make its future aerial refueling tankers, specifically, more survivable than they are today, but longer-ranged counter-air missiles would threaten to push them even further away from where the aircraft they support need them to be.

As well as these kinds of missile threats — which might be launched from platforms on the ground or at sea, or from other aircraft, or most likely a combination — it’s worth noting the other key vulnerability identified in this part of the report. This is the fact that today’s air forces “depend on a small number of easily targeted, forward-based airfields,” something that “will not be viable in 2050, and may not be viable today.” The susceptibility of these kinds of installations to attack, especially in the context of a future conflict in the Pacific, is something TWZ has repeatedly addressed.

Returning to the long-range counter-air weapons, the Department of the Air Force doesn’t mention any particular related programs, nor does it highlight any particular threat countries, although China is noted in the report as “the pacing challenge to the United States” out to at least 2050.

Indeed, it’s abundantly clear from the report that China’s rapid military developments are the primary reason why U.S. air dominance will be so threatened by 2050, although other countries, notably Russia, will likely have similar kinds of counter-air capabilities within reach.

“Against a pacing challenge, the current Joint Warfighting Concept already assumes that, in heavily contested airspace, air superiority can be achieved only episodically through pulsed operations,” the report states, reflecting the degree to which the U.S. military’s freedom of air operations is being eroded.

The result of this is the expectation of an entirely different kind of air war by 2050, one in which the United States is far less able to establish control of the air, whether defensively (in its own airspace) or offensively (in an adversary’s airspace).

The realities of these new conditions, the report contends, include the removal of the U.S. Air Force’s previously almost assured ability to have crewed fighters and bombers “operating from relatively secure air bases and able to survive multiple sorties once air superiority was established” and then to fly “extended strike ranges efficiently against the full range of land and sea targets.”

Not only will this new reality affect the Air Force’s “ability to deliver munitions at scale through bombing campaigns with acceptable loss rates,” but no longer having control of the air — other than temporarily — will affect how the U.S. military and its allies are able to conduct operations in all domains: air, land, sea, and space.

Returning to the very long-range counter-air missiles that will help bring about this change in air warfare, it should be noted that, while the report introduces these in terms of a new threat to the U.S. Air Force, there’s no reason to presume that the U.S. military won’t also be fielding weapons in this class by 2050 — or even before.

Concept art of the Long Range Engagement Weapon, or LREW. U.S. Department of Defense

In the realm of air-to-air missiles, the United States is already busy working on new types of weapons that will out-range the furthest-reaching missiles that it currently has in service.

As well as air-to-air missiles that are larger overall than those in use today, other ways of achieving longer range could include designs based around multi-stage rocket motors, as well as air-breathing engines, such as ramjets. In the past, we have also tracked U.S. interest in, among other things, throttleable “multi-pulse solid rocket motors” and novel “propellants, grain configurations, cases, and liners,” all of which would also be able to deliver greater range — as well as higher speed — compared to existing weapons.

By way of comparison, the standard U.S. Air Force medium-range air-to-air missile, the AIM-120 AMRAAM, in its longer-range D-model form, is generally assumed to be able to hit targets at a distance of around 100 miles. The official performance figures are classified and, in practical applications, a whole range of factors impact a missile’s reach, above all the energy and altitude state, as well as the direction of travel, of the launching aircraft and the target.

The U.S. Navy has fielded, at least on a limited level, an air-launched version of the Standard Missile-6 (SM-6), designated the AIM-174B, the range of which is also classified but should be far in excess of the AIM-120D, likely at least double and possibly triple the range. The Navy and Air Force are also jointly developing the AIM-260, another new air-to-air missile that will offer far greater range than current generation AMRAAMs, as well as other new and improved capabilities, but in a similarly sized package.

When it comes to air-to-air missiles, the requirement for carriage by a fighter means that it will still be a big challenge to have an air-launched weapon able to achieve a range of 1,000 miles — roughly 10 times the reach offered by the latest AMRAAM — by 2050. It should be noted, however, that size would not be such an issue for the B-21 Raider, the Air Force’s new stealth bomber that may well also find itself in some kind of air dominance role, or the soon to be modernized B-52. The F-15EX can also carry outsized weapons other fighters in the inventory cannot.

On the other hand, developing a surface-to-air missile with this kind of prodigious range is less of challenge, although still a tall order. With far fewer restrictions on weight and dimensions, such a weapon could be conceivably built today, although limiting it to taking on larger, lumbering targets, like tankers, transports, and support aircraft would likely be necessary.

When it comes to current threat capabilities, Russia claims its existing S-400 surface-to-air missile system can engage targets up to 250 miles away, although even then, this would be under absolutely ideal conditions against very particular target types. Its larger S-500, which is designed to provide theater ballistic missiles and other long-range air defense capabilities, has a purported maximum range of 370 miles. China has its own expanding array of similarly capable longer-ranged surface-to-air missile systems like the HQ-18 and HQ-19.

Whatever the launch platform, a counter-air missile with a 1,000-mile reach won’t be of any use at all unless it’s paired with and tied into a highly advanced and deeply networked ‘kill web’ of the kind the U.S. military is rapidly developing. Ultimately, it’s envisaged that advanced kill webs will play a critical role in rapidly identifying and selecting targets, before bringing effects to bear on them over very long distances. These kill webs are already increasingly meshing together multiple sensors, effectors, and support elements across air, land, space, surface, subsurface, and cyber domains and across the different military services.

The space domain is going to be absolutely vital for engaging aerial targets at extreme ranges. In the future, an airborne early warning aircraft will not be able to survive within its radar’s range of threat aircraft. Nor can it track targets a thousands miles away due to radar range limitations and, in many cases, the curvature of the earth. This is where space comes in.

The U.S. military is already working toward fielding new distributed satellite constellations that will be able to provide a global and persistent ‘air picture’ and generate targeting-grade tracks on threats anywhere, all networked in real-time. This, in turn, will mean missiles, air or surface launched, will not have to rely on the launch platform or existing intermediate nodes, especially increasingly vulnerable airborne early warning and control aircraft, to provide mid-course targeting and telemetry support. The weapons will be guided to their targets via the space-based tracking layer made up of hundreds or even thousands of satellites criss-crossing the globe. TWZ has explored in detail in the past how these kinds of space-based capabilities will be a major boon for American forces.

At the same time, China, especially, has been dramatically expanding its own space-based sensor architecture, including for long-range targeting purposes.

“The ability of the entire [U.S.] joint force to project power depends upon our success in space,” Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall said today during a talk that the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) think tank hosted. “If we do not deny China, in particular, its targeting capabilities … if we don’t deny that precise and real-time targeting capability, the whole joint force is at grave risk.”

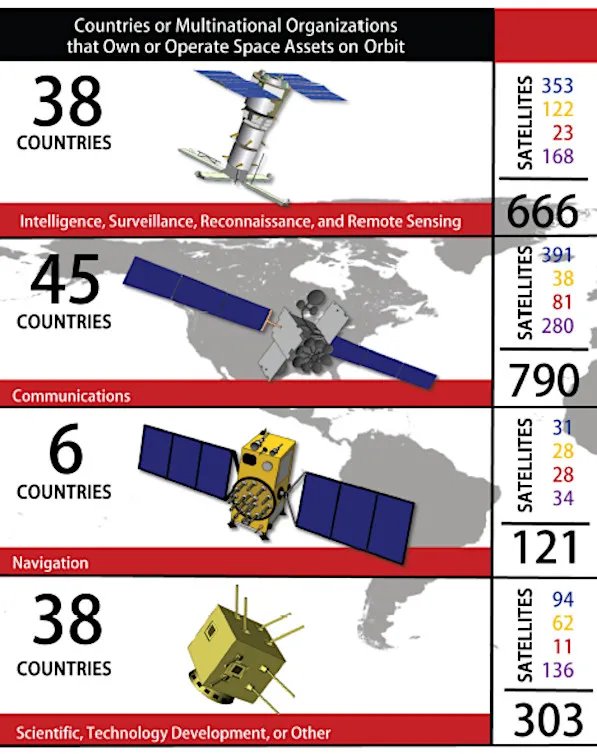

The Pentagon has been increasingly voicing its concerns about the fast-expanding network of Chinese intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) satellites that “could support monitoring, tracking, and targeting of U.S. and allied forces worldwide, especially throughout the Indo-Pacific region.”

In its 2024 report on Chinese military capabilities, the U.S. Department of Defense also discussed space-based targeting in the context of long-range precision strikes, noting that China “emphasizes the importance of space-based surveillance capabilities in supporting precision strikes and, in 2022, continued to develop its constellation of military reconnaissance satellites that could support monitoring, tracking, and targeting of U.S. and allied forces.” While this has, so far, been understood mainly in terms of the threat posed to targets on land and at sea, expanding the same satellite capabilities should also ensure that China is better able to ensure over-the-horizon targeting information in the air domain.

However the United States and its adversaries go about realizing their next generation of very long-range counter-air missiles, and whatever platforms end up using them, it’s already highly significant that the Department of the Air Force considers that the 1,000-mile-range will be broken in the next 25 years, and with the help of space-based sensors. This prospect promises to help usher in an entirely new air warfare reality — for better or worse.

Contact the author: thomas@thewarzone.com