The U.S. Air Force’s fleet of Sikorsky HH-60W Jolly Green II combat search and rescue (CSAR) helicopters will not be “particularly helpful in the Chinese area of operations,” one of the service’s top procurement officers has asserted. With planned HH-60W procurement already trimmed back, the Air Force is instead looking at “several” nontraditional options that would be able to recover downed aircrew from deep within contested environments, such as those that would be expected in any kind of major military confrontation with China.

This is a glaring and complex issue that The War Zone has been highlighting for years now, but this official admission, paired with recent procurement choices by the USAF, makes it clear that it is now becoming an undeniable truth within the DoD.

The latest details about the HH-60W and future plans for CSAR came to light yesterday, during a hearing on Air Force modernization by the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services’ Subcommittee on Air-Land. The key question on the status of the HH-60W and future CSAR plans was raised by Richard Blumenthal, a Democratic Senator from Connecticut. This is the same state in which the Jolly Green II is built by Sikorsky. That historic firm is now part of the Lockheed Martin Corporation.

Sikorsky was awarded a contract to build a new CSAR helicopter fleet to replace the aging HH-60G Pave Hawk in 2014. The award was initially for 113 Jolly Green IIs, but changing Air Force requirements, competing priorities, and budget constraints reduced that to 108 and then to even smaller sizes. At the time of writing, the Air Force only has 65 of these helicopters on order. As of September last year, 23 of the 65 purchased Jolly Green IIs had been delivered to the Air Force, as part of a program expected to be worth $4.1 billion in total.

Blumenthal stated that he was “very concerned about the Combat Rescue Helicopter,” the program that is providing the Air Force with the HH-60W, which conducted its first operational deployment earlier this year, to an undisclosed location in East Africa.

Blumenthal’s particular concern related to the Air Force’s plan to “terminate” the program, a reference to plans to shelve the purchase of 10 HH-60Ws in the 2024 Fiscal Year — effectively reversing a decision from the previous year’s budget, which you can read about here.

Even with those extra 10 helicopters, Blumenthal remarked, the Air Force will ultimately “only have 75 out of the 108 [HH-60Ws] that are thought to be necessary.”

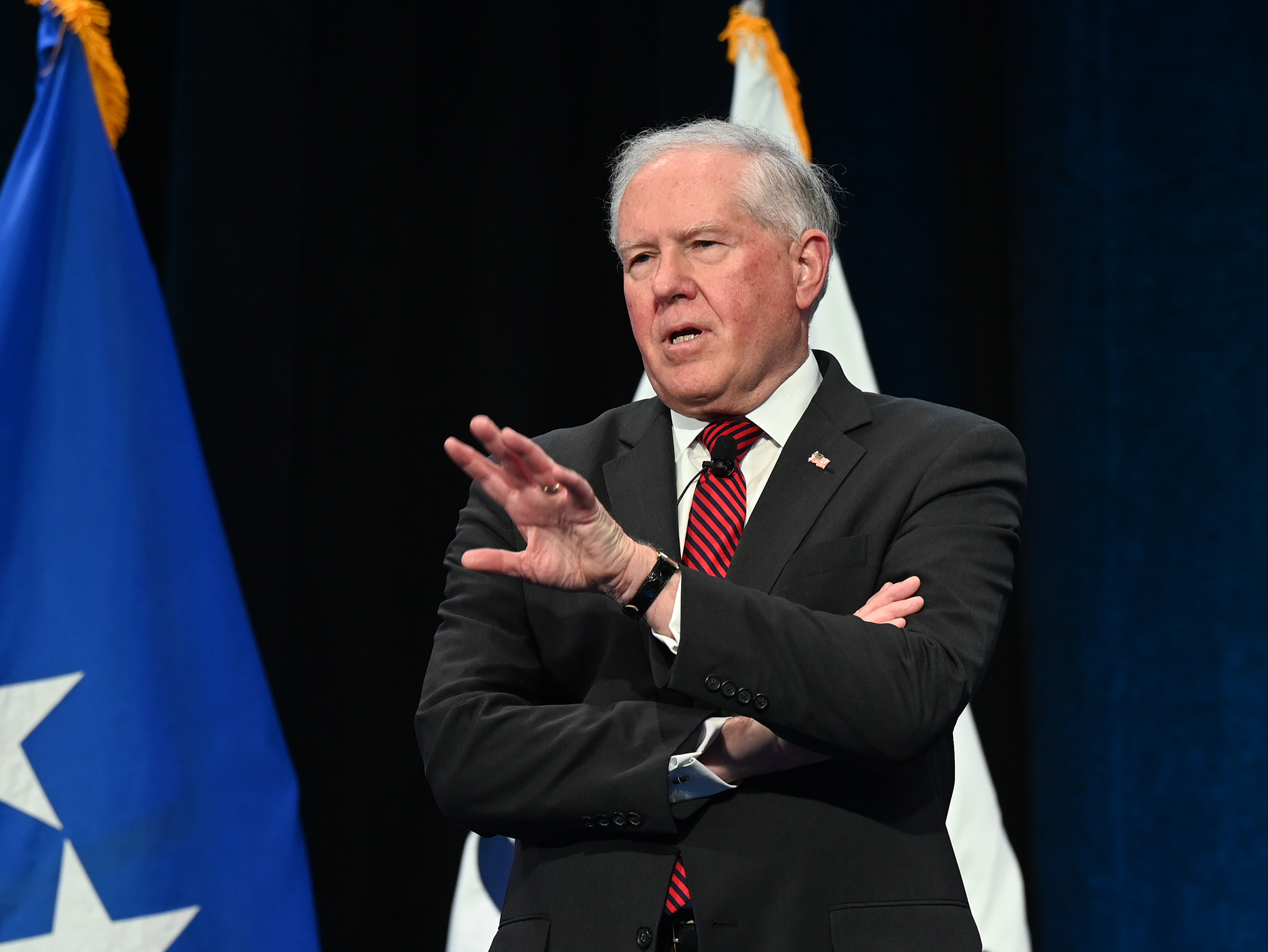

Andrew Hunter, the assistant secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics, refuted the claim that production of the HH-60W was being “terminated” and confirmed that the service “still has resources for 20 aircraft not yet on contract.” He added that the Air Force was currently “working through getting those 20 [helicopters] that have been appropriated on contract with Sikorsky,” with a decision on that possible in the next few days.

Once that happens, Hunter confirmed, the Air Force will be headed toward a total fleet of 85 HH-60Ws.

This is still significantly below the original plans to buy 113 HH-60Ws to replace the service’s increasingly rickety HH-60G Pave Hawks, which have been worn down after two decades of supporting the Global War On Terror.

Nevertheless, the Air Force seems to think that the reduced fleet will be enough for the time being, before new CSAR capabilities are added. Effectively, the Jolly Green II was developed and procured for a kind of lower-intensity warfare, or now a dated higher threat environment, that is fast becoming less relevant for the Pentagon as a whole, forcing a rethink of the entire CSAR mission. It’s worth noting, too, that the process of getting the HH-60W in the first place was notably protracted, leading to the helicopter prompting an immediate requirement for a series of major upgrades as a byproduct.

“This [HH-60W] fleet is for something very specific, it was purchased for Iraq and Afghanistan,” explained Lt. Gen. Richard Moore, Jr., the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Programs. “It is not particularly helpful in the Chinese AOR [area of operations].”

Lt. Gen. Moore added that there was a big distinction between CSAR — the mission flown by the HH-60W, which involves plucking endangered isolated personnel to safety in highly contested environments — and the broader mission spectrum of personnel recovery. The Pentagon defines the latter mission set as “the sum of military, diplomatic, and civil efforts to prepare for and execute the recovery and reintegration of isolated personnel.”

“There are literally thousands of platforms in the Department of Defense that can do personnel recovery,” Lt. Gen. Moore added.

With a continuing commitment to what officials termed the “moral imperative” of the CSAR mission, and of “not leaving anybody behind,” the Air Force is now having to address new challenges, specifically those introduced by the prospect of a confrontation or even full-scale conflict involving China in the Asia Pacific theater.

After all, there is a huge difference between a CSAR posture in an environment like Afghanistan, with established bases nearby and a strictly limited anti-aircraft threat. In comparison, a campaign in the Pacific would very likely see the Air Force — CSAR assets included — operating from distributed locations very far away from each other, under constant threat of attack both in the air and on the ground, and with an overarching requirement to penetrate deep inside denied territory. Clearly, while the HH-60W could still offer some useful support capabilities in the Pacific, a relatively short-legged standard helicopter is very limited in this kind of context.

The USAF’s migration to a combat aircraft inventory dominated by low-observable (stealthy) aircraft that are built to fly into heavily contested areas, fighting their way in and out if necessary, has also changed the CSAR equation. How can an HH-60W be expected to survive, even with low-flying tactics and electronic warfare and self-protection capabilities, in an area where a top-of-the-line, far faster, stealth combat aircraft could not?

For an aircraft like the B-21 Raider stealth bomber or the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) manned platform, which feature greater combat ranges than current stealthy tactical jets and can survive very deep inside enemy territory for long periods of time, the very idea of CSAR becomes even more bewildering.

Regardless, integrated air defense systems, which are becoming far more intertwined, complex, and capable, have made the prospects of a standard helicopter making it through such a mission much less probable, and the problem is only getting worse. Combining many assets to enable the survival of the CSAR helicopter force, assuming it could even reach a downed crew operating over such vast distances, is also very risky in such a deadly environment. It can turn a bad event into an outright major disaster.

Recalling the infamous BAT 21 rescue effort during the Vietnam War, Lt. Gen. James C. Slife, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for Operations, also stated at the hearing yesterday that, “No matter how dedicated you are, if you’re not in a platform that’s survivable to the threat environment, you end up losing more people trying to recover somebody than the person you lost, to begin with.”

The bigger question then is just what kind of platform, as well as tactics and strategies, could supplement the HH-60W for contested CSAR in the future.

“We’re actively looking at nontraditional ways in order to fulfill that moral imperative of leaving nobody behind,” Lt. Gen. Slife confirmed, without providing more details of what kind of platforms were being considered.

Lt. Gen. Slife did, however, state that both crewed and uncrewed CSAR solutions were on the table, among “several options.”

What seems clear is that the next generation of Air Force CSAR platforms will not look much like the familiar HH-60G and HH-60W.

Lt. Gen. Slife continued: “I think the one thing we can say is that helicopters — and I have 3,000 hours as a helicopter pilot — that fly at 115 knots refueled by C-130s with pararescue men that ride a hoist up and down is probably not the answer in our most stressing scenarios.”

This is not the first time in recent weeks that the issue of trimming back HH-60W orders in light of the increasingly hazardous nature of the CSAR mission has come up.

At a Pentagon briefing in March ahead of the Fiscal Year 2024 budget rollout, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall added more details on the earlier decision to truncate purchases of the new rescue helicopters.

“There are a lot of other assets around that, if somebody goes down at sea, for example, we could use to pick them up,” Kendall said. “We’re going to do it [the CSAR mission] with existing assets, either our own or provided by other military departments.”

“The scenarios that we’re most worried about are not the same as they once were,” Kendall continued. “When we were doing counterinsurgencies, and we were losing pilots in those kinds of situations, the needs were different. The acts of aggression like we’re seeing in Europe, or we might see [in] the Pacific … put us in a very different scenario.”

But Kendall also said there was nothing else new in the service’s latest budget proposal regarding other concepts for CSAR.

Clearly, however, these discussions are already going on, albeit apparently still at a very early stage. Otherwise, there could be capabilities, even in a very small capacity, in the classified realm, but that would not provide the mass needed to impact CSAR on a broad level in a major conflict, where multiple aircrews will likely be shot down over a broad area.

It’s hard to know what kind of platform options might be being considered, but it seems likely they extend far beyond traditional helicopters and even tiltrotors, the latter of which offer greater speed and range, but which will increasingly fall short of the requirements for operating in the most contested airspace. Still, in CSAR, speed is key. For every minute a crew is on the ground, their chances of survival plummet. There are also survivability advantages with that speed. The V-22 Osprey has shone in the aircrew recovery mission operationally and the Air Force already has an aircraft fully kitted out for penetrating into hostile airspace in the CV-22 variant. This prompts questions about why these advantages were not considered when recapitalizing the Pave Hawk fleet. Cost clearly was an issue, but saving money just to result in a far less applicable available mission set doesn’t make much sense.

The USAF could look to additional CV-22s and piggyback on the Army’s Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft program that now will be leveraging a variant of the tilt-rotor V-280 Valor. This seems outright logical if not inevitable at this point, but these aircraft would still have trouble penetrating deep into enemy airspace, but at least they have the range and enhanced speed to have a better shot at getting there at all.

We have examined in great depth decades of work to produce exotic aircraft capable of penetrating deep into enemy airspace for special operations and aircrew retrieval applications. This shadowy history, which you can read all about in this two-part series here and here, remains a question mark in the CSAR equation — both then and now.

But we do know that stealthy transport aircraft have gone from obscure niche concepts to center stage in the USAF’s collective consciousness in recent years as current transport aircraft are also vulnerable, even far from a core enemy target area, to modern air defenses.

The possibility of aircraft that combine jet speeds, some low-observable features, and vertical takeoff and landing capabilities is also being more widely considered. Still, this is many years away — likely decades — from becoming a reality.

There is also the glaring question of stealth helicopters, examples of which were used successfully in the raid to kill or capture Bin Laden. If this technology exists, why has it not been applied to the critical CSAR mission? Even basing stealthy helicopters forward aboard more survivable ships could help with some of the range and survivability concerns.

There have been previous proposals involving autonomous “air taxi” type recovery systems, which could be included among the uncrewed CSAR options the Air Force is now looking at.

Connected to this is the Air Force’s ongoing Agility Prime program, working with commercial industry to explore the concept of flying cars and what it would take to get designs like this rapidly into the air. In Air Force parlance, these flying cars are normally known as eVTOLs, or electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles.

Meanwhile, back in 2019, the Air Force Research Laboratory issued a call for proposals for a potential air taxi system that could be airdropped from a cargo plane or helicopter to downed aircrew, and that would then fly them to safety, carrying up to four at a time. A small, ultra-quiet autonomous air vehicle with short or vertical take-off and landing capabilities could be one way of getting imperiled personnel out of combat zones discretely, although the issue of safely delivering the air taxi to them in the first place remains.

There are also major questions about whether these kinds of vehicles would be able to operate over the kinds of ranges likely in an Asia Pacific scenario, even if this means just getting to a safer area for a traditional platform to retrieve the crew. Just how survivable they could be in the first place in such a hostile environment is another major question that needs to be answered. Regardless, they could be a useful capability, even if just for a limited set of circumstances.

These kinds of concepts often have Cold War precedents, including the U.S. Marines Corps’ efforts to develop small single-person helicopters and even ultra-light fixed-wing aircraft that could be inflated like a balloon. None of these proved to be practical, but the technological advances that have been made since then could make such propositions more practical today. There is even a possibility that even more novel concepts, such as jetpacks or rocket belts could be due for a comeback in this specific context, but they have, at present, very limited range.

The Cold War-era XROE-1 Rotorcycle, an ultra-light, compact, easily portable, and foldable one-person helicopter:

Other similarly exotic concepts for CSAR have been explored in the past, including the Rapid Aerial Extraction System (RAES), proposed by U.S. defense contractor Modern Technology Solutions, Inc. (MTSI).

Simply put, RAES involves dropping a line to a downed pilot before yanking them off the ground and towing them to safety. This is not an altogether new idea, with similar systems having emerged during the Cold War. As we discussed in the past, a new take on the concept could offer significant advantages in reliability and safety, as well as being something that could be fairly easily installed on a wide range of aircraft.

In one computer-generated video presentation, MTSI showed the RAES installed in a pod-mounted form on an Air Force A-10 attack jet. In a contested warfare scenario, other options could potentially involve RAES being integrated on a stealthier crewed or even uncrewed aircraft.

When it comes to the vast Pacific, where ‘tanker bridges’ that span thousands of miles will be needed to get tactical jets and other combat aircraft into any position to impact a conflict, something with great range beyond anything with vertical landing capability may be needed for SAR/CSAR. This is where flying boats and seaplanes may come in.

U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) is still working on putting its MC-130 Commando IIs on floats. These aircraft are designed to penetrate at low levels into enemy airspace and could survive on the outer edges of contested areas. They could land on water in some conditions and provide air-dropped gear to downed crews where they can not land. Operating from forward bases basically anywhere — no runway needed — also helps speed reaction time.

Far less optimized for contested operations, Japan’s US-2 flying boat, is also a potential solution that is available ‘off the shelf’ but totally lacks the MC-130’s deep and pricey sensor, communications, and survivability upgrades. Still, it is better suited than a notional MC-130 on floats for rescue operations across a broad maritime area with a better ability to land at sea in rougher conditions.

Then there are the various possibilities for extracting aircrew from hostile environments using altogether less orthodox tactics. In the past, for example, the Air Force has even encouraged the idea of stealing enemy aircraft as a means to escape, while the possibility of using networks of partisans or sympathizers in denied areas might also come back into vogue if the prospects of physically racing to the rescue simply become too problematic.

All in all, there appears to finally be a realization as to the real challenges the CSAR mission represents in this new era of aerial combat within the USAF. At least they are now openly discussing what will come after today’s traditional CSAR platforms that are unlikely to be able to perform all of their missions in future large-scale conflicts. And once again, the challenge to meeting this “moral imperative” is further driven by the fact that, in these kinds of scenarios, stealthy aircraft are likely to be flying much deeper into denied areas that are far riskier than any experienced in the past.

This, in a nutshell, is the paradox of fielding such aircraft in the first place: If stealth aircraft are designed especially to fly into denied areas, there’s always going to be the risk that they come down in those same areas, leaving aircrew requiring rescue from some of the most hazardous environments imaginable.

This is a hugely important but very ‘unsexy’ topic to tackle, but it’s a byproduct of a much larger USAF strategy that needs to be addressed, and soon.

Hopefully, that will happen and it will be interesting to see what kinds of CSAR concepts ultimately emerge from what is becoming an increasingly demanding set of requirements.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com