A report on the controversial close air support-focused flyoff between the A-10C Warthog and F-35A Joint Strike Fighter that took place between 2018 and 2019 has finally emerged. The declassified review, which was only completed last year and has been essentially buried until now, is heavily redacted and raises more questions than it provides answers in many areas. However, it does still offer valuable details that have not previously been made public even as the U.S. Air Force looks to retire the last of the Warthogs no later than the end of the decade.

Project on Government Oversight (POGO), an independent nonprofit, obtained a declassified copy of the report via the Freedom of Information Act and litigation against the U.S. government and published it this week, along with its own analysis. The document, which was produced by the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Test and Evaluation, or DOT&E, is dated February 2022. The comparative testing ran from April 2018 to March 2019. The flyoff was only conducted to meet a demand from Congress that had been included in the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for the 2017 Fiscal Year.

One of the things that is immediately unclear from this report is why it took nearly three years to produce this final product in the first place or why its core findings were never announced publicly or even distributed to stakeholder communities in the military. It is The War Zone‘s understanding that very few people had previously seen any portion of this document, or details from it, and that it was not provided to members of the A-10 community or F-35 communities. In essence, it has been effectively ‘buried.’

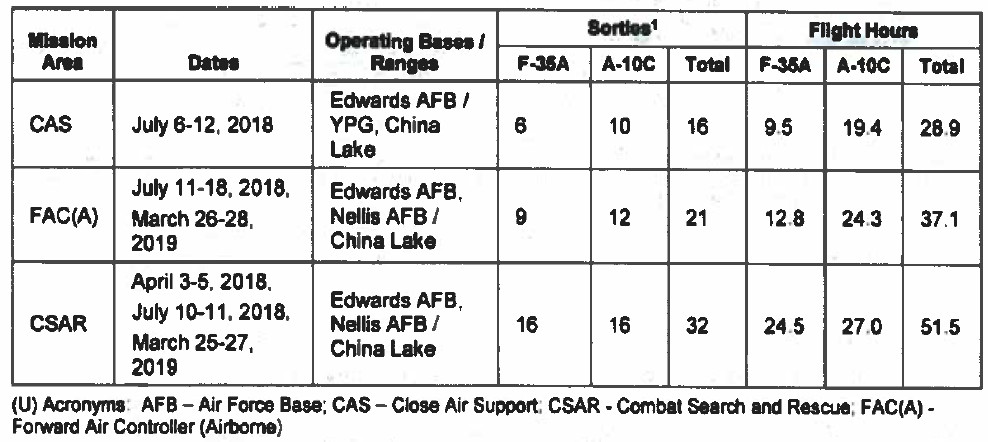

The unredacted portions do contain a useful overview of how the flyoff was planned and ultimately conducted. The Joint Strike Fight Operational Test Team, or JOTT, led the comparative testing, which was conducted as part of the larger F-35 Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E) process. All test sorties were staged from Edwards Air Force Base in California and consisted of mock missions conducted over ranges at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, also in California, as well as Yuma Proving Ground, an Army facility in neighboring Arizona.

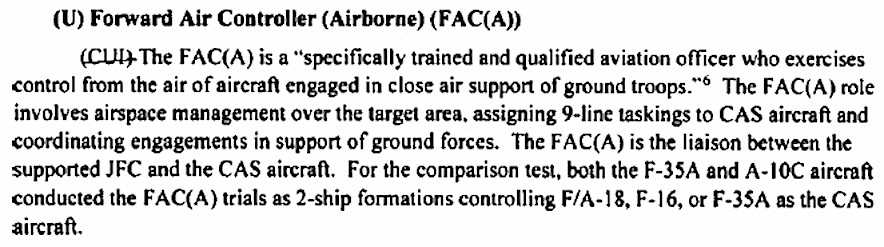

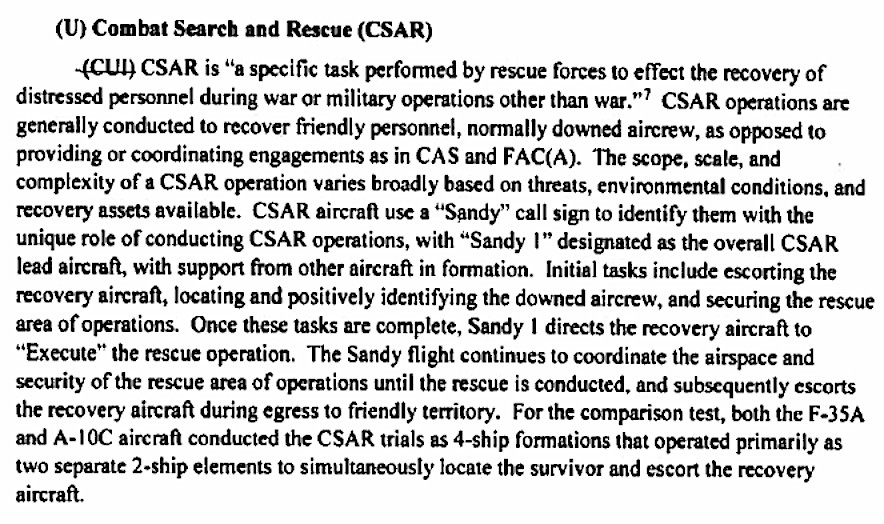

The flyoff focused on the relative abilities of the A-10C and the F-35A to perform three distinct mission sets: close air support (CAS), airborne forward air control (FAC[A]), and combat search and rescue (CSAR). Unclassified official definitions of those mission sets from the reports are reproduced below.

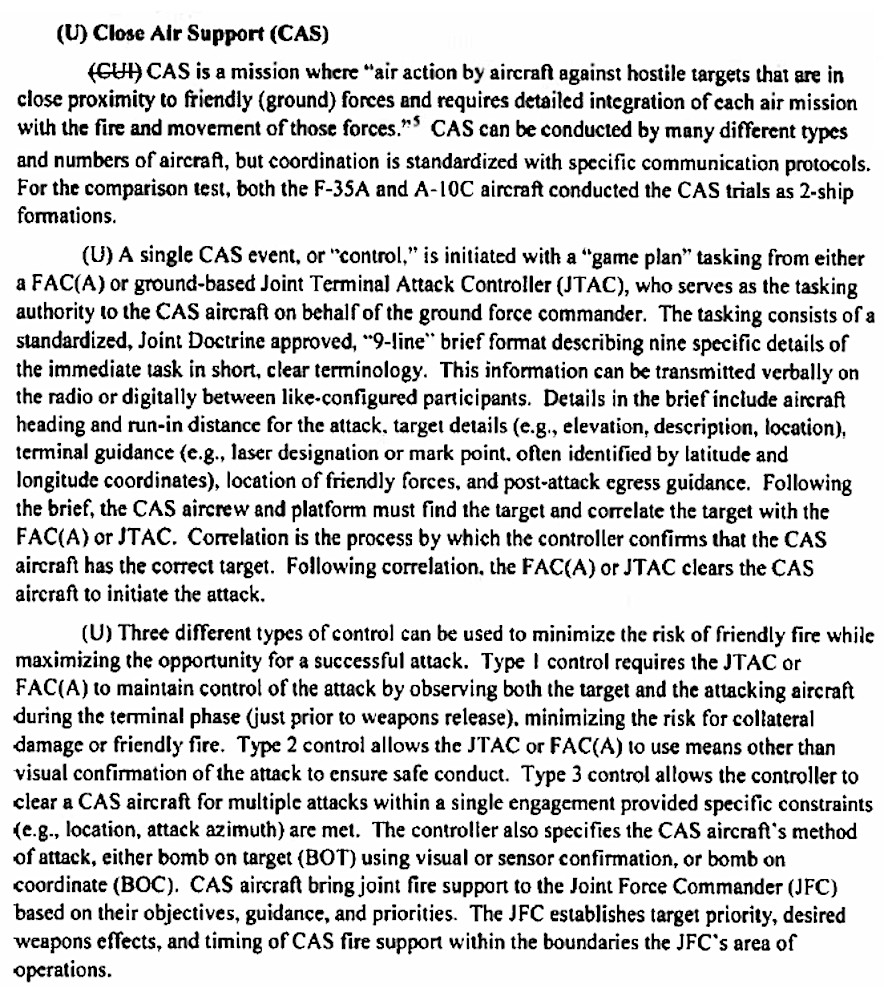

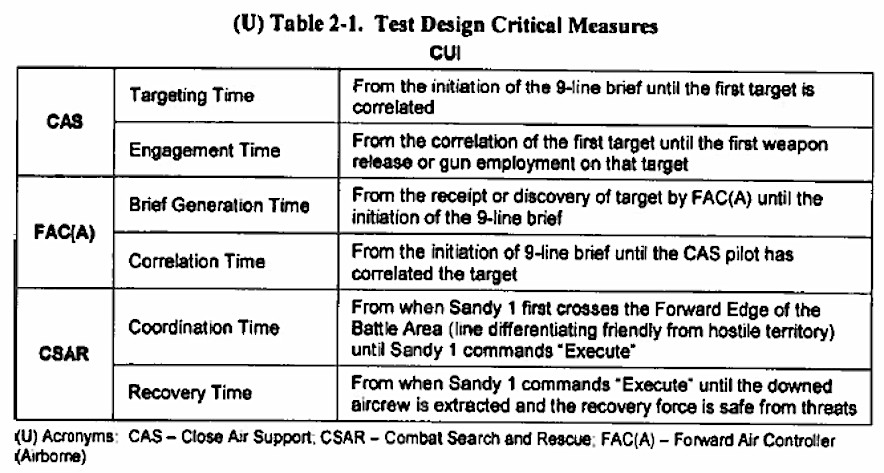

The ability of the A-10 and the F-35 to perform each of the three mission sets was judged on a variety of factors, but the report lists two critical metrics for each one. For CAS this was targeting time and engagement time. When it came to FAC(A) the focus was on brief generation time and correlation time. Lastly, coordination time and recovery time were the primary measures of performance with regard to CSAR. Unclassified definitions of these timing metrics are shown below.

Test sorties were conducted under conditions meant to simulate “low-threat ‘permissive’ and medium-threat ‘contested’ environments,” according to the report. “High-threat missions were not included in this comparison test because the F-35A, along with the F-35B and F-35C, is being thoroughly evaluated during F-35 IOT&E in high threat scenarios versus modern, dense SAM [surface-to-air missile] and fighter aircraft, missions for which the A-10C was not designed.”

Specific details about what types of threats were presented during the low or medium-threat test sorties in the flyoff, or how they were represented, are limited in the unredacted sections of the report. It does say that the “contested environment scenarios included a limited set (in numbers and capabilities) of surface-to-air missile (SAM) threats, and no airborne threat[s].” There is also a mention of simulated shoulder-fired surface-to-air missiles, also known as man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS). No mention at all is made in the unredacted portions of the report about electronic warfare threats, which are another major source of concern for the U.S. military, especially in future higher-end conflicts.

The U.S. military has multiple ways of simulating a diverse array of mock air defenses for testing and training purposes, including real examples of threat systems obtained through various means, high-fidelity mock-ups, and emitters designed to mimic various types of radiofrequency emissions.

A-10s and F-35s involved in the flyoff flew a combined total of 117 and a half flight hours across 69 sorties. A full breakdown of sorties and flight hours, as well as when and where those test runs occurred, across the three mission sets is seen below.

Nowhere in the unredacted portions of the report is any definitive statement about whether the A-10 or the F-35 was deemed to be superior for conducting any of the three missions in either permissive or contested environments. The first bullet point in the executive summary, which might offer a broad general conclusion about the results of the flyoff, is entirely redacted.

“The F-35A was able to conduct all three missions in both low- and medium-threat environments,” according to the report. In addition, the Joint Strike Fighters “often conducted suppression/destruction of threat air defense systems in contested environment to proceed in the assigned mission.”

There is no similar unredacted statement about the A-10’s overall adequacy to perform CAS, FAC(A), or CSAR missions.

A partially redacted section strongly indicates the flyoff concluded that more F-35 sorties than A-10 sorties would be needed to prosecute the same number of targets in permissive environments. This makes sense given the Warthog’s substantially larger payload capacity. However, this portion of the report also notes that “the number of sorties necessary to complete the same mission objectives in contested environments would depend on air defense suppression plans.”

The unredacted portions of the report also acknowledge significant limitations in the comparative testing that was conducted, and more can be inferred from other information provided.

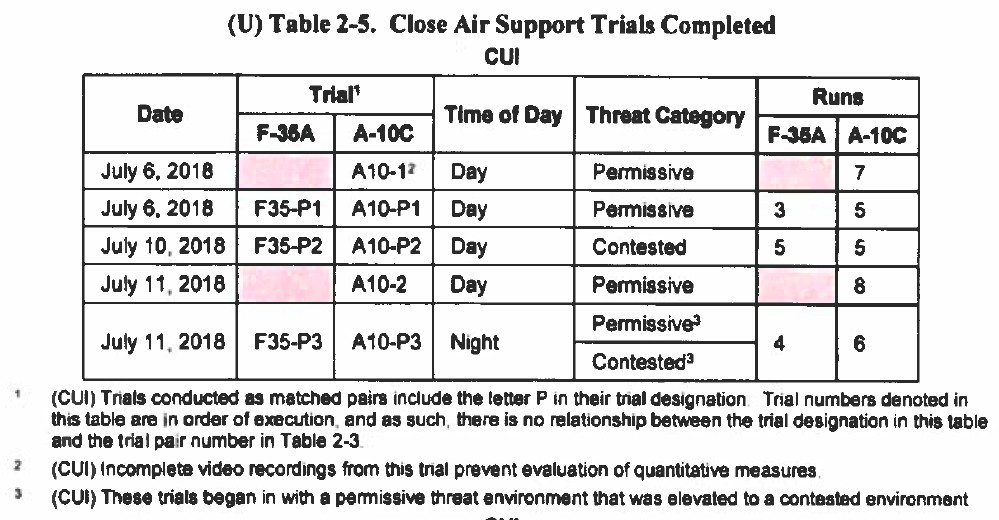

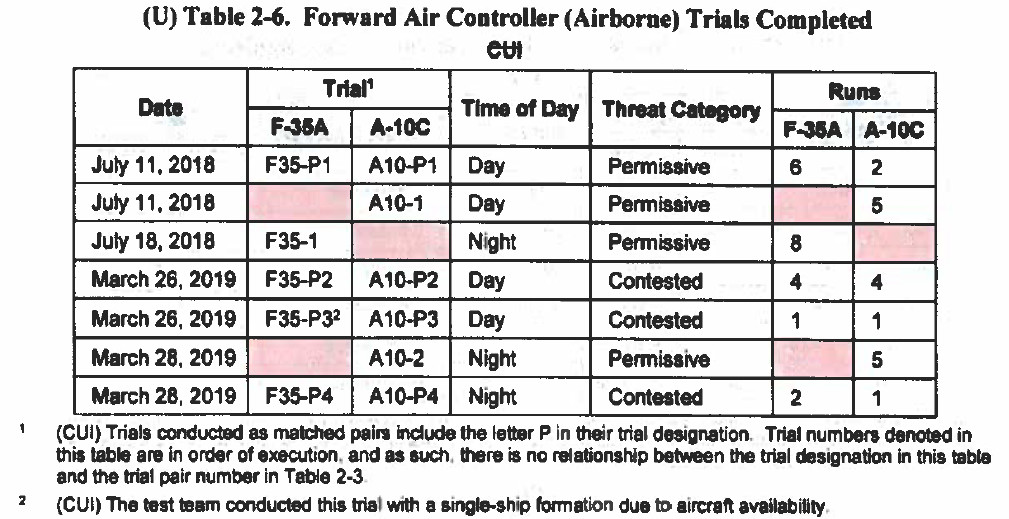

For one, the flyoff team did not follow the approved test plan, did not fly all of the originally planned sorties, and did not ensure there were matching sorties for all test events that were conducted. All of the test sorties were supposed to be in matched pairs (one A-10 sortie and one F-35 sortie with as close to the same parameters and conditions as possible), the point of which was to provide equivalent data sets for analysis. As can be seen in the breakdown earlier in this piece, A-10s flew more CAS and FAC(A) sorties than F-35s did, and Warthogs had more total flying time during testing relating to those mission sets, as well as CSAR.

More details breakdowns of the test sorties across the three mission areas are provided below.

“The comparison test was adequate to compare the mission effectiveness of each aircraft in a limited set of operationally-representative conditions, even though the test team did not conduct the test completely in accordance with the DOT&E-approved test plan,” the report insists. “The data collected are sufficient to inform the conclusions in this report and fulfill the requirements of the NDAA.”

“The sample sizes available for analysis provide sufficient data to draw the conclusions in this report,” it adds. “The gaps do not detract from the value of the data for the measures used to compare the two aircraft.”

No further justification for this is provided in the unredacted portions of the report.

In addition, the report acknowledges a lack of relevant specialized training requirements for F-35 pilots relating CAS, FAC(A), and CSAR mission sets at the time of the flyoff.

“To minimize the impact of this training shortfall on the comparison test, F-35A pilots previously qualified for FAC(A) and CSAR in the A-10 or other aircraft were used when possible, which was the ‘majority of the trials,” according to the report. “Much of the F-35A pilot light hours were in aircraft other than the F-35A (primarily F-16 or A-10), while A-10C pilot light hours were primarily in the A-10.”

It is worth noting here that making use of F-35 pilots with previous A-10 experience would seem to be a logical course of action that could also help preserve the specialized skill sets and knowledge base found in the A-10 community as those aircraft are retired. However, there are serious potential pitfalls in such a strategy, especially given the steps the Air Force is (or isn’t) taking now.

“The common misconception between USAF leadership and we, the A-10C community, is that we are ready to die on the hill to keep the A-10 alive forever. The reality is quite the opposite,” Patrick “BURT” Brown, an A-10 pilot and Air Force weapons officer, wrote in a piece earlier this year for The War Zone. “What we care about most is keeping the corporate knowledge of counter-land tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) alive regardless of the airframe. Presently, the threat of that knowledge dying off is very real given that the A-10C is being divested with no plan for follow on aircraft.“

“Within the USAF, the A-10C community is the only one that still produces Forward Air Controllers (Airborne), known as FAC(A)s,” Brown added. “This is a troubling data point not because FAC(A) missions have been on any recent Air Tasking Orders (ATOs), but because it signals that the USAF is willing to let that skill set die with the A-10C.”

“The skills learned and honed by practicing the FAC(A) mission set are invaluable in any counter-land operation. The F-35 could do this mission, but they don’t. The F-16 has done this mission, but they don’t today,” he continued. “Between all the other high-end missions they must maintain proficiency in, CAS and other counter-land competencies are now relegated to ‘just-in-time’ training for the USAF’s multi-role fighter communities.”

POGO’s Dan Grazier has echoed many of these points, as well.

“The fight to save the A-10 has always been about preserving the institutional knowledge of the community rather than keeping one aircraft program flying,” Grazier also told The War Zone. “That being said, the problem with making sure most of the F-35 pilots were A-10 veterans was that most F-35 pilots don’t train for the attack role now.”

“This was supposed to be an operational test,” he added. “Operational testing is supposed to be done using the typical operator rather than specialized test pilots so you see how the aircraft being tested works in the hands of the people who will actually fly it in combat. That didn’t happen in this case.”

The unredacted portions of the test report highlights a number of other areas where just how operationally representative the flyoff appears limited.

“The overall environment chosen by the test team for the comparison test was a simplified representation of typical combat environments,” the report says. The use of relatively basic mock targets positioned in largely flat and open locales, even those meant to simulate enemies in built-up urban areas, is something that had already come up back in 2017 when the first details of the flyoff emerged, also through POGO. Concerns were raised even then about whether this could give F-35 pilots an unfair advantage given that the targets would be easier to spot, even from higher altitudes.

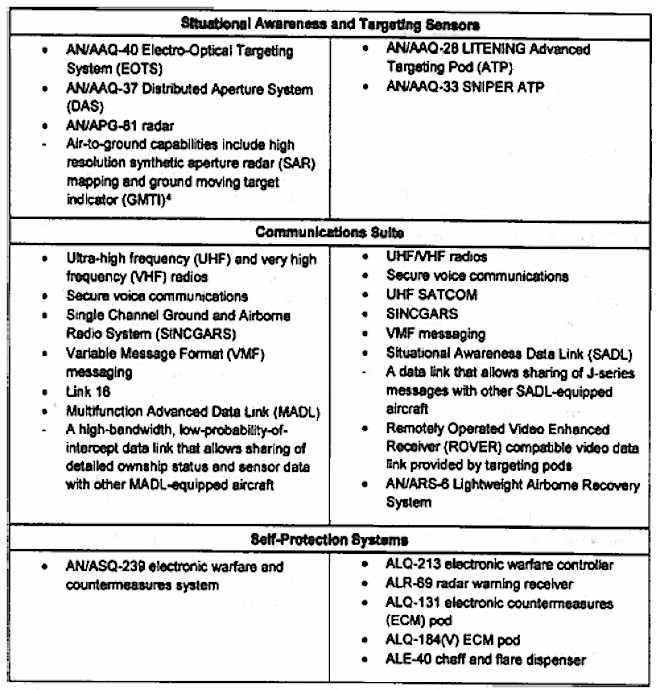

All Joint Strike Fighters have a built-in, but increasingly Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS) that is based on technology now approaching two decades old. An Advanced EOTS is expected to be added to F-35s that receive the Block 4 upgrade package, but A-10Cs are flying now with more capable podded targeting systems. This means the level of detail in the targeting system video is inferior on the F-35 compared to the A-10C with updated targeting pods.

A-10s typically fly a very low altitudes, and are much slower than F-35s, both of which can be beneficial for finding and engaging threats that might be more concealed. A partially unredacted section also indicates that there might be added value in the Warthog’s tactics when it comes to the employment of GPS-assisted precision-guided munitions.

“The test team did not record the slant range to the target with the generated coordinates, so ts effect cannot be directly assessed. Even so, tactics typically caused A-10C pilots to fly closer to the target than F-35A plots, which could explain some of the difference in the measured location errors,” the report says, though the context is not entirely clear. “Target location error only affects the use of GPS-aided weapons. In any case, the location error is sufficient to cue another CAS aircraft’s targeting pod.”

The report also says “time-on-station can be a key contributor to the overall success of each of these mission areas [CAS, FAC(A), and CSAR],” another area in which the A-10 excels, at least in lower-threat environments.

Furthermore, despite being an evaluation of performance in missions directly related to personnel on the ground, “there were no live ground forces maneuvering or operating in conflict against each other on any mission, primarily due safety to range restrictions,” according to the report. Only one day of testing, part of the CAS portion of the flyoff, involved the use of real, but inert ordnance, as well. In all other instances, the ordnance the A-10s and F-35s employed was entirely simulated.

The A-10 can be loaded with a much more diverse array of munitions and other stores, including multiple types of precision-guided missiles, rockets, and bombs, than any F-35 variant, on top of the Warthog’s aforementioned greater payload capacity. A-10s can carry far more ammunition (up to 1,174 rounds) for their iconic 30mm GAU-8/A Avenger cannons. F-35As have a built-in 25mm GAU-22/A cannon feeding from a magazine with a maximum capacity of just 182 rounds. F-35B and C variants have no internal guns, but can be armed with a podded GAU-22/A with a smaller magazine.

An unrelated section of the flyoff report also notes that F-35s cannot carry different ordnance on their underwing pylons and their internal weapon bays at the same time for unclear reasons. The use of those underwing stations also negates the Joint Strike Fighter’s stealthy characteristics. The A-10 is well known for its ability to carry mixed ordnance loads on individual sorties, which offers more flexibility for engaging different kinds of targets.

The report also highlights the limited ability of the F-35A, at least at that time, to communicate directly with personnel on the ground. Ostensibly to create an even playing field, voice communication was therefore utilized almost exclusively during the comparative testing.

This, in turn, appears to have put A-10C drivers at a disadvantage in some situations since they were not allowed to use their very capable digital communications capabilities while also lacking modern enhancements found on the Joint Strike Fighter that are designed to help reduce pilot workload.

“This limitation likely slowed down A-10C performance timelines in CAS and FAC(A) roles in comparison to the F-35A,” the report notes.

Back in 2017, when reporting on the initial details about the flyoff from POGO, The War Zone had specifically highlighted the A-10C’s extensive ground-support-focused communications capabilities, particularly the Remotely Operated Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER) system. ROVER, which has been continuously improved upon since it was first introduced in the early 2000s, allows equipped aircraft to pump sensor feeds straight to JTACs and other personnel down below in near real-time, significantly improving coordination.

The F-35 Joint Program Office has since taken steps to integrate a ROVER-like video data link onto the Joint Strike Fighter. However, it is not immediately clear how far that work progressed in recent years and how many, if any, F-35s now have this capability.

Inversely, “A-10C pilots reported a significantly lower workload than F-35A pilots in the task-intensive FAC(A) mission.” The reasons for this are not clear from the unredacted sections of the report.

Regardless, an unredacted portion of the executive summary included a recommendation to “improve digital communications, video data link capability and interoperability with 4th generation aircraft,” as well as “fix the F-35A gun” and “develop training programs to further improve F-35A effectiveness in these missions.”

Accuracy issues with the F-35A’s 25mm cannon, which persisted at least into 2020, are well known. That same year, it emerged that certain jets were experiencing worrisome cracking as a result of using the gun at all. The full extent to which this issue may have been mitigated since then is not immediately clear.

POGO says separate documents it has reviewed show that the Air Force still does not have CAS-focused or related specialized training requirements for its F-35A pilots and is not expected to put them in place in the coming year, either.

Altogether, “you can’t really consider this [flyoff] as a close air support test because there weren’t really any friendly troops. If the tests had been done at [U.S. Marine Corps Base] Twentynine Palms or the [U.S. Army’s] NTC [National Training Center], the JOTT could have incorporated real maneuver units performing realistic combined arms scenarios,” POGO’s Grazier told The War Zone. “That would have greatly increased the rigor of the entire endeavor by making the pilots distinguish between friendly and enemy troops. At NTC, they could have incorporated Soviet-era equipment. The JOTT could have crafted scenarios where the role players on the ground worked to camouflage their positions.”

In addition, “rather than observing actual hits or misses, officials judged the results based on cockpit video and self-reported outcomes by the pilots and participants on the ground,” Grazier separately noted in his own separate analysis of the report. “This created an opportunity for officials to manipulate the results based on desired outcomes and operator bias.”

Grazier further raises the point that it is very curious that unspecified “range safety restrictions” are repeatedly cited in the report as the reason why the scale and scope of the comparative testing were curtailed in many regards despite inert training munitions only being used in one day’s worth of testing.

It is worth pointing out here that the U.S. military’s current definitions of CAS include missions wherein aircraft are directed to targets by controllers who do not have direct visual confirmation of them. In many ways, this seems to have been the primary type of CAS reflected in the flyoff.

This kind of ‘remote’ CAS often blurs the line between that mission set and interdiction, a technically different mission type that is more focused on engaging enemy forces before they reach friendly units. This is also a reality that predates the flyoff.

“It is sometimes the case that sorties tasked for [close air support] may wind up supporting strikes that look more like interdiction, or vice versa,” a spokesperson for the U.S. Air Force’s top command in the Middle East told this author back in 2015 specifically about A-10 strikes against ISIS in Syria.

This all may well speak to how the Air Force envisions providing CAS in a future conflict, especially to forces on the ground in high-threat environments. There are also potential pitfalls to relying on this kind of air support, as has been shown on multiple occasions, even with platforms more specifically suited to these kinds of missions.

In 2014, an Air Force B-1B bomber infamously killed five Army soldiers and an interpreter in a botched CAS strike during a firefight in Afghanistan. The incident was blamed in part on degraded communications and the inability of the bomber’s targeting pod to see infrared strobe lights marking friendly positions.

The following year, also in Afghanistan, one of the Air Force’s AC-130U Spooky special operations gunships mistakenly destroyed a hospital operated by international nongovernmental organization Doctors Without Borders. That incident also stemmed in large part from a breakdown in communications between the gunship and controllers on the ground, the latter of whom were not in a position to see the actual intended target. A near real-time video link on the AC-130U was also notably non-functional at the time, preventing the crew from directly sharing imagery of what they were looking at before the strike was authorized.

“As someone who has a great deal of experience in combined arms training, I much prefer to have aviation support destroy targets before I can see them. That helps ground forces generate tempo in a running fight,” POGO’s Grazier, a retired Marine officer who served tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, told The War Zone. “I have had aircraft drop close enough to my position to feel the effects of the blast. I’ve even had brass fall into my tank from a helicopter firing on a target as they flew overhead. I was glad they had trained to the most difficult and delicate scenario.”

Without being able to see the full flyoff report it is hard to truly assess the results and the justifications for those conclusions. At the same time, it has long been hard to give the Air Force the benefit of the doubt when it comes to the A-10, an aircraft the service has been actively trying to rid itself of since it first entered service in the 1970s.

The War Zone has detailed the many known instances in the past of the Air Force deliberately hamstringing the A-10 fleet and manipulating data to present it in an especially poor light. It is also known the service buried a set of requirements it had drafted regarding a dedicated A-10 replacement.

It is no secret that the Air Force did not want to conduct the flyoff at all, with then-Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh publicly describing it as a “silly exercise.” The Congressional mandate for comparative testing had come after a scandal in which another Air Force general had suggested to his subordinates that defending the A-10 to members of legislators was tantamount to treason. Before that, the Air Force had also suppressed a short official documentary that presented a very positive picture of the A-10.

At the same time, it is increasingly hard to argue that the utility of the A-10, especially in higher-end conflicts, is steadily diminishing, despite the substantial upgrades it is still receiving. There are already growing questions about exactly how the U.S. military will conduct CSAR at all in high-threat environments where stealthy aircraft like the F-35 are expected to operate. The Air Force has notably truncated its purchase of HH-60W rescue helicopters for this reason and is now exploring various alternatives to traditional CSAR.

The comparative test report notes that A-10 and F-35 pilots involved in the flyoff repeatedly raised the idea of using F-35As to escort A-10Cs on CSAR missions. CSAR force packages have included fighter cover since before the Warthog entered service and this particular pairing could make good sense. Stealthy F-35As would be capable for neutralizing aerial threats and hostile air defenses in support of the mission, as well as just providing critical situation awareness, all thanks in no small part to their extensive sensor fusion and electronic warfare capabilities. Still, whether this would all be enough to adequately execute CSAR missions in a high-threat scenario is questionable and give the A-10s a decent chance of surviving is variably debatable, depending on the scenario.

The A-10 community is otherwise very actively looking for additional ways it can contribute in higher-end conflicts, including as launch platforms for decoys to help clear the way through enemy air defenses.

All of this is becoming increasingly moot as the Air Force is now pushing ahead with plans to retire the entire A-10 fleet by 2030, if not before then. After years of pushback from Congress, lawmakers now look to be more inclined to finally let the Warthog go. Whether the contents of this report, which should be available to legislators in full, have any impact on their views remains to be seen.

In addition, U.S. Special Operations Command is now moving forward with its own plans to acquire dozens of dedicated light attack aircraft specifically to perform close air support, armed overwatch, and other related missions in permissive environments. Though the total number of OA-1K Sky Warden aircraft that are expected to eventually enter service will be much smaller than the size of the A-10 fleet currently, this could help make up for some of the resulting capability shortfalls.

A big question that remains is what the Air Force will or won’t do in the end to preserve the institutional knowledge that the A-10 community has built up over the years.

“If the services are going to be stuck relying on the F-35 to fill the attack role, the best solution would be to assign an adequate number of squadrons to specialize entirely on the mission,” POGO’s Grazier told The War Zone. “HQ Air Force should transfer all transitioning A-10 pilots to those squadrons to concentrate their knowledge that they then pass on to the newly assigned attack pilots and issue appropriate Ready Aircrew Tasking Memorandums.”

“That is not happening,” he continued. “The Air Force isn’t even pretending to train F-35 pilots for the role now so accumulated attack pilot knowledge will very rapidly evaporate.”

We will have to wait and see whether or not more details about this flyoff might now begin to emerge with the final release of at least a portion of the final test report. Regardless, the A-10’s career with the Air Force looks to be ever more firmly coming to an end.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com