On April 12, 2017, one of the U.S. Air Force’s WC-135 Constant Phoenix aircraft, which scoops up air to search for tell-tale signs of nuclear activity, landed at Kadena Air Base on the Japanese island of Okinawa. The plane’s arrival wasn’t surprising given widespread concern North Korea was prepping a sixth nuclear test coupled with reports of a potential American military response.

“U.S. intelligence is always on alert for a possible North Korean weapons test,” an unnamed individual from the U.S. Intelligence Community told VOA on April 13, 2017. North Korean leader “Kim Jong Un wants his country to be validated as a nuclear power and a test would further that goal.” This new nuclear test could coincide with the annual Day of the Sun, a massive, annual national holiday commemorating the birth of the country’s founder and Kim Jong Un’s grandfather, Kim Il Sung. It would be North Korea’s sixth reported detonation of a nuclear weapon.

But the WC-135W Constant Phoenix’s arrival just added one more aircraft to an existing armada of spy planes and drones on and around the Korean Peninsula. Whenever a U.S. official says the American government is closely monitoring the situation in North Korea, aerial snooping is undoubtedly an important source of that information.

The reclusive Communist regime has long been a major point of interest for America’s military. The United States and North Korea technically remain at war, bound only by a long-standing ceasefire agreement. Still, the Pentagon, as well as other U.S. intelligence agencies, has become more and more focused on the country’s activities in recent years.

On Oct. 9, 2006, the isolated dictatorship conducted its first reported nuclear test at the remote Punggye-ri site, which experts believed failed function properly. In the next decade, the country’s government set off four more devices. On top of that, the expanding and improving North Korean missile arsenal, which might be able to carry those devastating weapons, has become increasingly a matter of concern for the United States and its allies.

“Pyongyang’s evolving ballistic missile and nuclear weapons program underscore the growing threat,” Air Force General John Hyten, head of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) told Senators during a hearing on April 4, 2017. “It continues to defy international norms and resolutions, as demonstrated by a number of provocative actions this past year, including their fourth and fifth nuclear tests.”

Getting imagery and other details about those experiments and associated tests sites would be essential to understanding the true state of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. America’s array of powerful spy satellites would be one option. Unfortunately, satellites have regular orbits and it generally takes time to adjust them into new positions. This generally makes them best suited for long-term surveillance of static points.

The Pentagon’s Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS) employs multiple types of satellites and sensors to address some of these issues and provide greater coverage. According to defense contracter Lockheed Martin, the constellation can watch for the heat signature of enemy missile launches and track them in flight, gather details about those weapons and their capabilities, and simply provide a broad picture of activities down below. The system may even be sensitive enough to track smaller objects like aircraft and artillery rockets and can reportedly watched the shoot down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2017.

Closer to earth, spy planes and drones are almost constantly zipping around North Korea. The Air Force and the Army have spy planes and unmanned reconnaissance aircraft permanently deployed in the region specifically to keep watch on the country and its bellicose government.

On the Air Force side there is the 5th Reconnaissance Squadron, the 82nd Reconnaissance Squadron, and the Detachment 1, 69th Reconnaissance Group. The 5th’s U-2S Dragon Ladies are situated at Osan Air Base in South Korea, which sits less than 20 miles from the capital Seoul and about 50 miles from the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating the country from North Korea. The 69th keeps a small number of RQ-4A Global Hawks at Andersen Air Force Base on Guam and often sends them on temporary duty to bases in Japan.

The U-2s don’t fly directly over North Korea, as they would likely be too vulnerable to the country’s air defenses to do so even in a combat situation. However, with its long endurance, the aircraft can still patrol around the edges of international air space for hours on end, and peer deeply into the secluded country.

This would put them more than close enough for various sensors packages to potentially pick up useful intelligence. Though best known historically for its ability to take pictures while directly over a particular place of interest, the Dragon lady can carry the Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar System-2 (ASARS-2) and the Senior Glass electronic intelligence suite.

ASARS-2 would allow pilots to fly up and down the Yellow and East Seas, grabbing radar imagery well inland of the North Korean coastline. The exact range of Senior Glass’ components is classified, but it is reasonable to assume it could detect and intercept North Korean radio chatter and other electronic emissions far enough away to keep the Dragon Ladies out of any imminent danger.

Able to fly at high altitudes, the U-2 could conceivably use a slanted flight pattern to point the long-range, hyperspectral cameras in the Senior Year Electro-optical Reconnaissance System 2 (SYERS-2) or even the wide-angle Optical Bar Camera at targets along the border, as well. Customary international law would let the planes fly within 12 miles of the country’s coastline.

For some time prior to June 2008, the Air Force nicknamed these so-called “multi-intelligence” U-2 missions focusing on North Korea as Sable Game. Then for unknown reasons, the 9th Reconnaissance Wing, which controls the 5th in Osan, began referring to the flights as Ginger Game sorties. It is possible this name has changed again since then.

Satellite data links, known as Senior Span and Senior Spur, mean the spy planes can send back some of this information back to base while still in flight so analyst can begin picking it apart. The Air Force has the 694th Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Group at Osan in part to help “exploit” this kind of data.

Intended as an unmanned replacement for the U-2, the RQ-4A can carry many of the same sensors and perform many of the same functions. Having to fly from Guam would reduce how much time the Global Hawks could spend near North Korea, but dispatching them from Japan greatly increases their utility over the Peninsula.

Every summer, from May to October, the 69th sends its aircraft to Japan ostensibly to get the drones out of the way of typhoons. This year, no less than five RQ-4s will be sent to Japan. On April 10, 2017, the Global Hawks arrived at Yokota Air Base for their 2017 deployment. In the past, smaller detachments, usually just a pair of the large unmanned aircraft, have gone to Misawa Air Base.

The RC-135V/W Rivet Joints from the 82nd Reconnaissance Squadron focus on listening in on other country’s military units and fly throughout the Pacific from Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Japan. Unlike the U-2s with their single pilot, the Rivet Joints can carry more linguists and analysts on board to begin looking into information immediately. Data links let the crews pass both raw information and any analysis back to base.

Since 2006, Rivet Joint missions have occurred under the nicknames Sable Wind and Ginger Wind. If it’s not already becoming clear, the words “sable” and “ginger” have and may still refer to Air Force spying around North Korea, while the second word indicates the actual aerial intelligence platform.

In addition to these Air Force assets, the Army’s 3rd Military Intelligence Battalion has a whole fleet of smaller, shorter range intelligence gathering aircraft based at Camp Humphreys, less than 100 miles south of Seoul. As of June 2015, this included eight RC-12X Guardrail Common Sensors (GRCS), three EO-5C Airborne Reconnaissance Low-Multisensors (ARL-M), and three so-called “Saturn Arch” aircraft, according a table the service released as part of a contract announcement.

The RC-12X is a militarized twin-engine Beechcraft King Air light utility aircraft with a signals intelligence (SIGINT) setup that can find and listen in on enemy communications. The four-engine EO-5C, which uses the de Havilland Canada DHC-7 airframe, has similar capabilities, along with synthetic aperture radar and powerful day and night-capable video cameras. You can regularly spot the ARL-Ms flying along the DMZ, scanning for any activity on the other side of heavily guarded border.

We don’t know the exact sensor suite in the Saturn Arch aircraft, which the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA) first fielded in 2010 to help find improvised explosive devices in Afghanistan. Contractor-operated Bombardier Dash-8 aircraft carried the gear, which likely included some combination hyper-spectral cameras, laser-imaging systems, and airborne ground penetrating radars. These systems would be able to pick out changes in the terrain indicating someone had been digging or even spot suspicious objects buried close to the surface.

In 2013, the Army’s Intelligence and Security Command, which had already assisted NGA with the project in Afghanistan, took over the Saturn Arch program completely. Two years later, three of the four of the aircraft had moved to South Korea. Though there is little concern about IEDs in South Korea, North Korea does have a long history of trying to dig tunnels under the DMZ for secret agents and commando teams. The sensors on the Dash-8s could potentially hept spot this kind of covert activity as well as keep an eye on physical changes across the DMZ.

In March 2017, the Army also announced it was sending a company of MQ-1C Gray Eagle drones to join the 2nd Infantry Division, which has elements throughout South Korea. The pilotless planes can perform attack and reconnaissance duties already, thanks to a electo-optical system that can see during the day and at night. The service plans to eventually buy a detachable SIGINT pod for the Gray Eagle that could expand the aircraft’s intelligence gathering capabilities as necessary.

And then there’s the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 72, the unit overseeing the U.S. Seventh Fleet’s aerial patrol and reconnaissance forces. P-3C Orion and P-8A Poseidon patrol aircraft and EP-3E Aries II spy planes rotate through deployments to the unit’s bases at Naval Air Stations Atsugi and Misawa Air Base in Japan. From there, they make routine trips to South Korea proper for training exercises. The EP-3E Aries IIs are dedicated intelligence gathers, but all three types could help monitor North Korean developments.

The P-3s and P-8s are multi-purpose aircraft that can hunt submarines and surface ships. As such, they have full-motion cameras that work during the day or at night, as well as powerful radars. These systems can easily do double duty as surveillance equipment scoping out targets along the coastline. There is also a good possibility the Navy might decide to ultimately replace the EP-3Es with an intelligence-focused variant of the P-8.

The Poseidon already has strong electronic intelligence gathering capabilities and In 2014, the service tested a version of the P-3’s shadowy Littoral Surveillance Radar System, dubbed the Advanced Airborne Sensor on the P-8. This cumbersome but incredibly capable system will be coming online in an operational form soon. Also, the P-8 has been tested with what appears to be an elaborate communications podthat could make it a major player in the signals intelligence gathering game, and may allow the 737 derivative to take over some of the EP-3’s missions.

The Air Force also routinely rotates other aircraft from its fleet of airliner-sized RC-135s to bases in Japan. From there, they conduct both scheduled patrols and contingency missions in response to potential crises.

The RC-135S Cobra Ball and RC-135U Combat Sent have very different missions. The Air Force’s three Cobra Balls have specialized gear to track ballistic missile launches, which is especially important when it comes to North Korea. The two Combat Sents have equipment to detect and analyze electronic emissions from sites on the ground. Among other things, this means they can find and determine the relative capabilities of radar installations, a key component in figuring out the actual strength of an air defense network. This information could be an important part of planning any strikes against well-protected North Korean targets such as missile test facilities, regime targets or nuclear sites.

The Combat Sents have flown Ginger Sent sorties, suggesting a specific focus on North Korea. The two Cobra Balls operate as part of unified, world-wide STRATCOM-led effort to track long-range missile activity – even in friendly countries like India and Israel – called Olympic Titan. The Air Force’s pair of Constant Phoenixes are similarly part of STRATCOM’s larger nuke monitoring mission, Glass Titan.

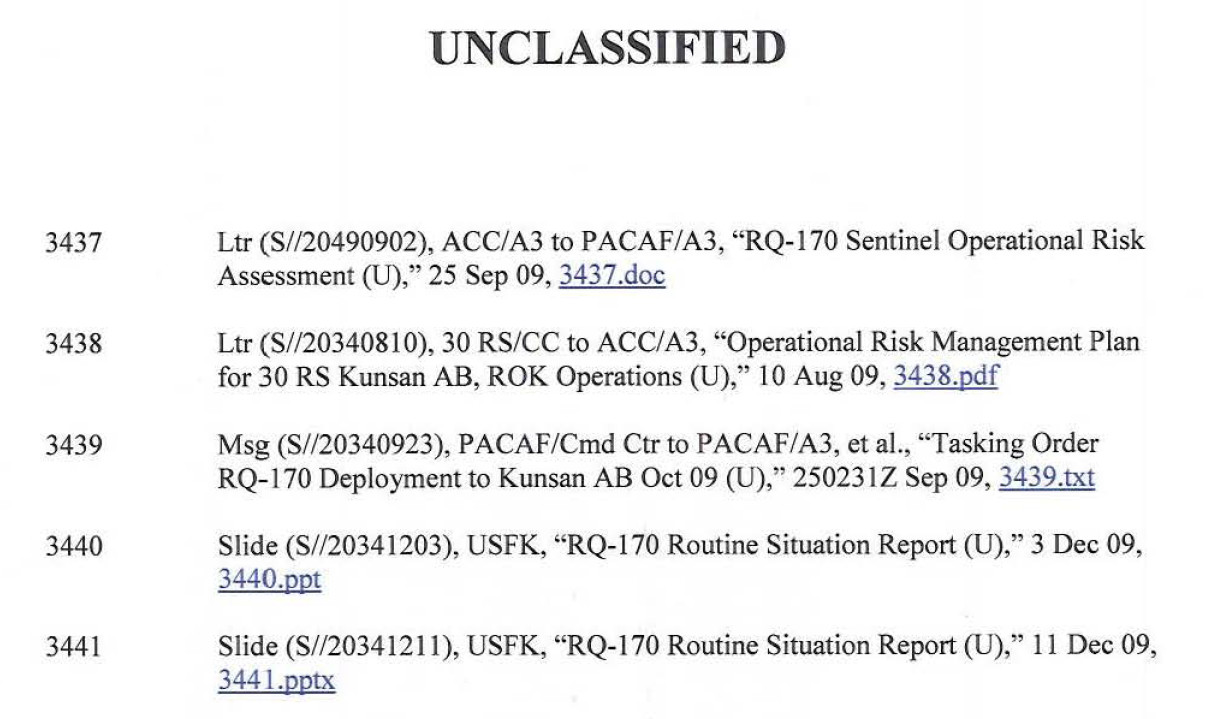

There is also the strong possibility the Air Force may be flying one of its more shadowy spy planes or drones deep into North Korea. In September 2009, the secretive 30th Reconnaissance Squadron sent stealthy RQ-170 Sentinels to Kunsan Air Base in South Korea. While we don’t know exactly what their missions from Kunsan entailed, the deployment came less than five months after North Korean authorities conducted their second nuclear test at Punggye-ri, which appeared to be successful.

What we do know is that the Sentinels are exactly the kind of asset the Pentagon would use to sneak deep into a denied territory like North Korea to spy on sensitive locations. With the apparent preparation for a sixth nuclear test, the RQ-170 could very well be flying highly classified missions over North Korea, examining its nuclear and rocket facilities and patterns of life around regime targets. The so called RQ-180, supposedly a high-flying penetrating strategic reconnaissance top secret aircraftthat is known to exist even by the USAF’s own admission, might well be flying new missions over the country as well.

And then there’s a slew of other aircraft that could perform varying levels of surveillance if necessary. Land bases in the region host E-3 and E-8 radar planes, E-8 maritime patrol aircraft, F-16 and F/A-18 fighter jets with advanced radar warning receivers and camera-equipped targeting pods, and advanced F-35 Joint Strike Fighters with their integrated electro-optical sensor and electronic support measures suites.

In January 2017, the U.S. Marine Corps sent an operational contingent of F-35Bs to the Marine base at Iwakuni in Japan for the first time, making them available for various missions in the event of a crisis. They are currently operating in South Korea right now. The Air Force’s F-22 Raptor’s have also made surprise visits to the Peninsula and surely they put their uncanny ability to sniff-out radar and other electronic emissions to use.

F/A-18s and F-35s could operate from carriers – like the USS Carl Vinson, which started heading for the Korean Peninsula this week – or amphibious ships. A supercarrier’s air wing is equipped with a cadre of E-2 Hawkeyes that can monitor aerial movements deep into North Korean airspace. Marine Corps aircraft, including helicopter and fast jets, can strap on highly capable electronic surveillance and jamming pods, like the Intrepid Tiger II, to keep tabs on enemy electronic emissions and communications along the DMZ.

With various radars and other surveillance gear, American cruisers, destroyers, and most importantly submarines all have the ability to snoop around North Korea’s coastlines, too. President Donald Trump specifically mentioned the presence of subs in the area during an interview with Fox Business Network’s Maria Bartiromo on April 12, 2017.

In all, North Korea may be one of the most heavily monitored places on earth. And we have only mentioned America’s surveillance assets. South Korea and Japan have their own fleets of spy aircraft with varying capabilities.

Whether Pyongyang decides to set off another nuclear bomb or not, it’s safe to say the Pentagon has the ability to keep a close watch what’s going on inside the reclusive country.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com