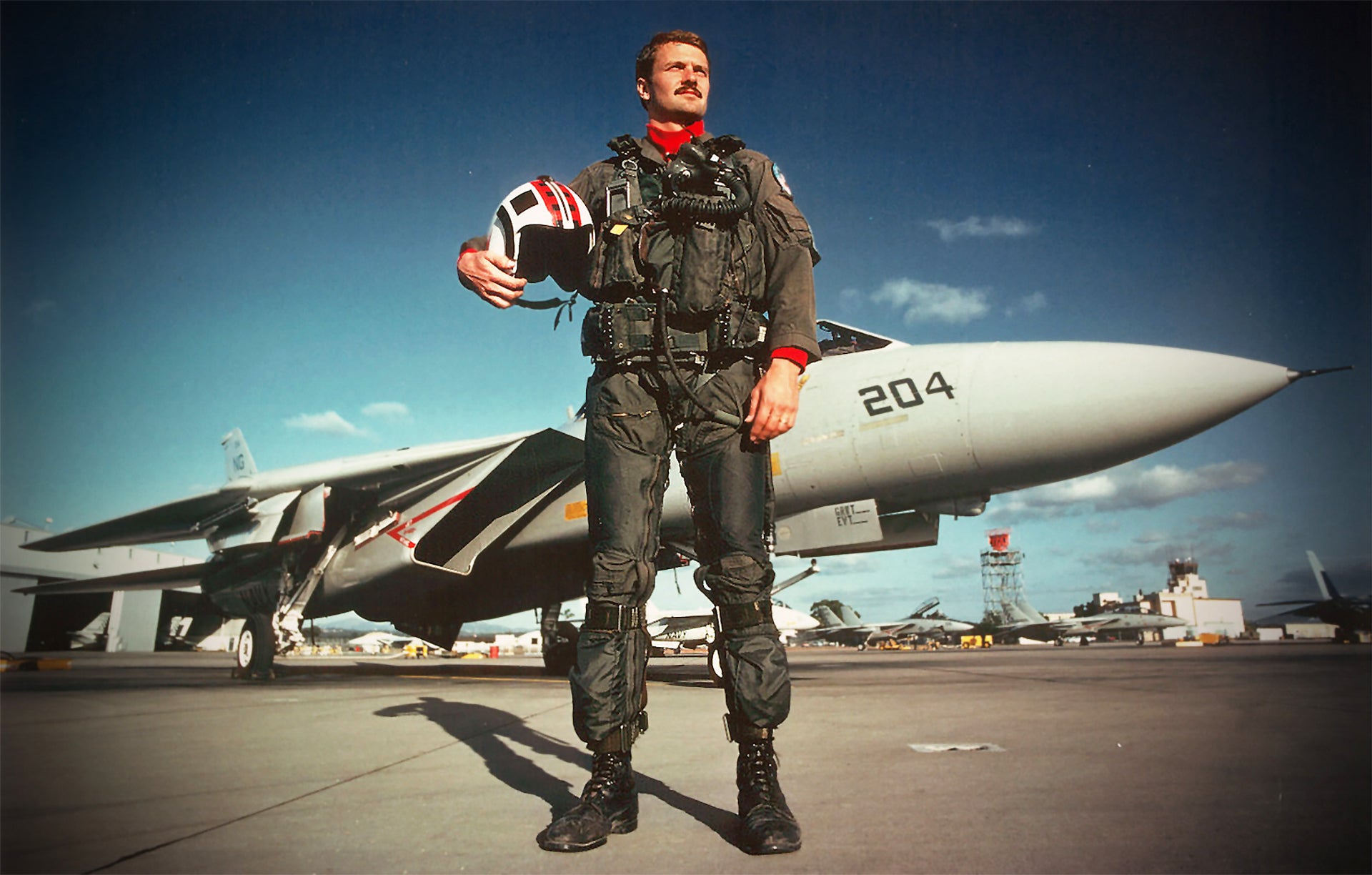

In 1982, Paul Nickell was a “nugget” Naval Aviator heading to his first fleet assignment with VF-24 “Renegades” at the now fabled Naval Air Station Miramar near San Diego—also known as Fighter Town USA. His mount was the still somewhat unpredictable but fiercely powerful Grumman F-14A Tomcat. Not long after arriving he would set sail aboard the USS Ranger for his first cruise. In this the third chapter of our multi-part series about Paul’s adventures flying Navy fighters in the 1980s—from chasing SR-71 Blackbirds to having an engine explode beneath him—he gives us an incredibly intimate view of what it was like for a pilot taking the still adolescent Tomcat to sea for their very first time.

Perfect timing

I arrived at VF-24 in the fall of 1982. The Renegades had recently completed a Westpac cruise aboard the USS Constellation (CV-64) and were starting workups for their next deployment aboard USS Ranger (CV-61) which would begin in the summer of 1983. It was perfect timing for myself and a RIO from my Replacement Air Group (RAG) class. Arriving at the beginning of the turnaround meant that we would have the benefit of all of the workup training and “at sea” periods before we actually deployed. I was immediately impressed by the professionalism of the squadron, and at the same time the great spirit that the aircrews displayed.

Squadron life was unlike anything that I had experienced up to this point in my aviation career. I was no longer a student. Oh I had a tremendous amount to learn, but for the first time since I started flying, no one was filling out a grade sheet on me and debriefing my performance. That’s not to say that we didn’t debrief and learn from our training, but we focussed on what went well and what we could improve on, and to a large extent it was self critique. It was both refreshing and liberating!

Another new thing was that I now had a job within the squadron, as opposed to being just a student pilot. I was in charge of the “First Lieutenant Work Group.” I never knew where that name came from, but it was the group that kept our squadron spaces clean and well maintained. Additionally, since the squadron would be making it’s next deployment onboard Ranger, all of the spaces that we would inhabit when we went aboard had to be prepared for our arrival. The job definitely kept me busy, and during that time I worked closely with the squadron Executive Officer (XO) and got to know him very well. He was a Vietnam veteran, where he had flown the F-4 Phantom. He loved life, and lived it to the fullest. Unknown at the time, our paths would stay close together for the remainder of our time in the Navy.

Chasing Blackbirds and evading SAMs

Initially, the flight schedule was pretty slow for me, but it still provided more flights than the slow pace that the RAG had. The pace increased fairly quickly though as the squadron progressed through its turnaround. Our Operations Department, otherwise known as “Ops,” did a great job scheduling me on all sorts of varied training flights. On one mission with two Tomcats, we flew into the restricted areas northwest of Los Angeles and ran intercepts against SR-71 Blackbirds. It was great training for the Radar Intercept Officers (RIO) flying intercepts against very high and fast targets.

The speeds and altitude differences made the intercepts very challenging, arriving in valid missile launch parameters only for fleeting seconds. From a pilot’s perspective, I remember it being a very stressful flight because as wingman I spent a lot of time flying in close formation at night in the clouds (commonly referred to as ”in the goo”) as we transited back and forth to the restricted area.

One mission that I really enjoyed was flying low level routes. It was generally an exercise in navigation and timing, and the Tomcat had a reasonably reliable navigation system to help out. However, we always had topographic charts with routes and timing drawn out on them as a backup. The great part was the sense of speed that you experienced at very low altitude, and also the sight seeing. The bad part was that there was very little margin for error, and very little time to recover if anything went wrong.

We also did low level intercept missions. I remember one in particular where we were in a restricted area in the Sierra Nevada Mountains with two Tomcats and we were running intercepts down through narrow gorges. It was like some of the video games that are available today, except the rocks were very real and the scenery was absolutely breathtaking. Other flights included going up to the Death Valley and Panamint Valley areas and practicing evading the surface to air missile (SAM) threats. It was fun for the pilots, but miserable for the RIO’s. Typically it involved all sorts of octoflugeron maneuvers in which only the pilot knew what was coming and the RIO was just along for the ride. In an actual SAM situation the RIOs would have been completely looking outside for missiles, but in this environment there were no real missiles, only electronic indications of missiles airborne.

Finicky cats

Probably the bulk of our training flights were air combat maneuvering (ACM) missions. We would fight about any other type of aircraft available. Typical ACM flights were against A-4s and F-5s and were usually flown in the Socal area west of San Diego or just east of Yuma, Arizona. At other times we had the opportunity to fight Navy and Marine F-4s, and also hosted Air Force F-15s.

The one thing that we didn’t do was fight 1 versus 1 with other F-14s (1 V 1 similar). Shortly before my arrival at VF-24, the squadron had lost a Tomcat flying 1 V 1 similar. The problem with 1 V 1 similar is that since you were fighting aircraft of equal capabilities, it all boiled down to aircrew capabilities. Usually they would limit engagements to rear quarter missiles and guns, so the fights would often quickly degrade into groveling for a shot, and because of engine problems, that was not a good place for the F-14A.

At slow speed and high angle of attack, with the engines in full burner, the F-14A’s TF30 turbofan engines were prone to compressor stalls. Any air disturbance into the intakes, possibly caused by jet wash or yaw, could cause a compressor stall, and a compressor stall on one engine in this situation could lead to a flat spin due to thrust asymmetry. That’s what happened in the movie Top Gun, and that’s what happened to the Renegade F-14.

The Renegade crew actually recovered the aircraft from the spin, which may have been a first, but the motors had cooked themselves from being stalled for so long, and they would not restart. Eventually the crew had to eject. The end result was that in VF-24, we did not do 1 V 1 similar until several years after I joined the squadron, and after a very scripted 1 V 1 similar program was put into place.

Not long after I arrived at VF-24, one pilot and one RIO were selected to attend the Topgun Power Projection course. They were both in their first tour with VF-24, and both had completed the previous cruise aboard Constellation. They were chosen to attend the course by the squadron CO, based upon their performance in the squadron up to that time.

Depending upon available slots, most fighter squadrons got to send two crews through the course during a normal turnaround period between cruises. At the time, I knew very little about Topgun, other than that they provided adversary support. As the crew progressed through the course, I would see them passing through the squadron on their way to and from Topgun training missions. It quickly became obvious to me that the instruction they were receiving was far above anything I had ever been exposed to. Also they would soon become the leaders in VF-24 with respect to fighter tactics based upon their six weeks of exposure to the navy fighter tactics authorities (the Topgun staff). Although I wasn’t in any position to attend Topgun at the time, I set my sights on attending during the next squadron turnaround.

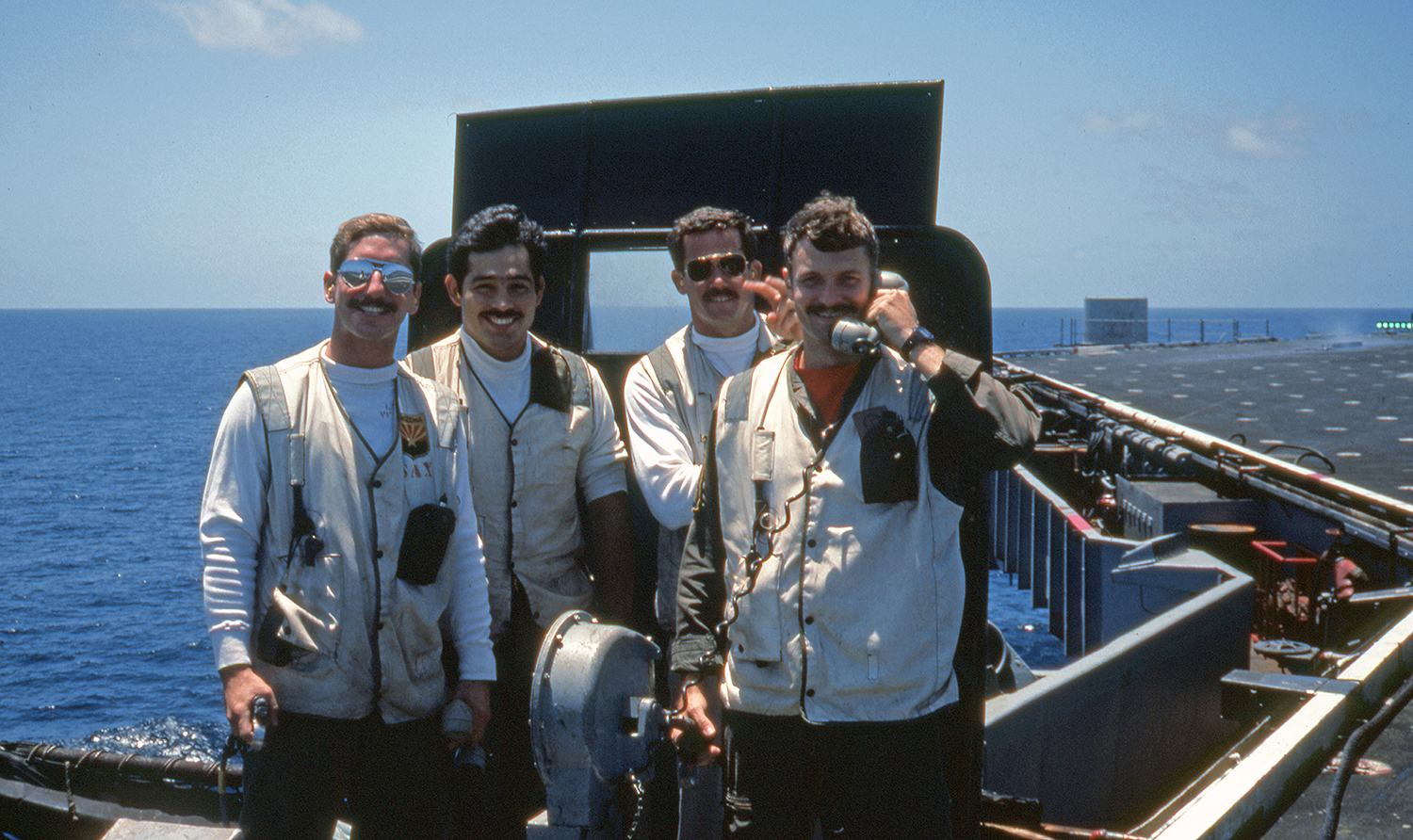

Spinning up for deployment

As our turnaround progressed, preparation for our next cruise intensified. We did a “Gun Det” at Miramar. “Det” was short for detachment, and detachments normally meant that you deployed to someplace other than your home base. Dets were always fun because they brought the squadron together and built great camaraderie. Unfortunately, because money was tight at the time, we were not able to deploy to another base, so we did all of our gunnery out over the Pacific, while operating from Miramar. If you couldn’t leave your home base, I’ll have to say that San Diego was a pretty good place to be stuck!

For the det, the squadron was divided up into four teams, which competed for the most target hits. We shot at towed airborne targets, and without going into all the details, we were able to get an accurate count on the hits for each pilot. At the end of each day, we would watch all of the day’s gun camera film and debrief from it. Although gunnery was to a large extent done by the pilots, the RIOs played an important role in monitoring the pattern being flown and locking up the target on each firing run.

Shooting the M-61 cannon in the F-14 was a kick in the pants. We were limited to 50 round bursts, and that only took half a second to complete. We were definitely slinging some lead! At the end of the det we had a kangaroo court with awards, both serious and humorous, and all in all, it was a great week of work. I had done a lot of rifle shooting in high school, and air to air gunnery in the F-14 came pretty naturally to me. I did well with it, and that would influence my future role in the navy.

Other dets included a two week Red Flag exercise at Nellis Air Force Base, and an air wing det to NAS Fallon, in Nevada. Unlike today, there was very little integration between the Air Force and Navy in the early ’80s. Red Flag was my first exposure to working with the Air Force, and it was definitely different. Red Flag was much bigger picture and larger scale training than I had ever experienced. It involved helos putting people on the ground, B-52s airborne, and everything in between. It seemed the biggest threat while we were there was getting sent home by the Air Force for flying into the wrong piece of airspace. We were constantly skirting around the Tonopah Test Range and Area 51, using only topographic maps and landmarks. We constantly made light of all of the Air Force’s areas to avoid and all of their rules, but they were really serious about them. We were threatened a few times, but fortunately none of our aircrew were ever sent home.

Soon after Red Flag, we went to NAS Fallon for two weeks with all of the squadrons in our air wing, Carrier Air Group 9 (CAG-9). CAG-9 was composed of one helo squadron, an E-2 squadron, an S-3 squadron, an A-6 squadron, an EA-6 squadron, two A-7 squadrons, and two F-14 squadrons. All of these squadrons would deploy together on our Ranger cruise. Fallon was a great place to fly out of, located in the high desert with high and rugged terrain to the east where the ranges were located. It also didn’t have all of the Air Force rules that Nellis did. The ranges were fully instrumented so that missions could be recorded for debriefing purposes and also simulated missile shots could be taken and recorded. It also had simulated surface to air missile threats available. Early on we did a lot of part task training, but as we progressed through the det, the scale of our exercises got larger until the end where we were conducting large scale coordinated strike missions.

“Paddles” in training

Intermixed with these detachments, we were starting to conduct at sea periods as an air wing aboard Ranger. Initially it simply involved going out to update our carrier qualification currency. Each pilot got several day and night traps, but other than the Landing Signal Officers (LSOs, but also sometimes referred to as “paddles”), none of the aircrew stayed aboard the ship. Following that we did a ten day at sea period, a five week at sea period, and then our final Operational Readiness Evaluation (ORE) for the carrier and air wing which lasted about a week. All of this was done in the waters off the coast of southern California.

When I checked into VF-24, I told the Operations Officer and the current squadron LSO that I was interested in becoming an LSO. I felt that seeing carrier type landings from the opposite perspective, on the ground watching the aircraft approach and land, had really helped me survive Tomcat carrier qualifications in the RAG. Becoming an LSO was a big undertaking, but I felt it would help me be the best carrier pilot that I could be, and also the squadrons were always looking for pilots interested in taking on that responsibility. Initially it involved working with the squadron LSO during field carrier landing practice (FCLP) periods, attending a two week LSO school, and then working with all of the air wing LSOs aboard the ship.

Ultimately, once I was qualified as a squadron LSO, the performance of the entire squadron coming aboard the boat would be my responsibility, and it was a big one. During these workup at sea periods I began to get experience waving aircraft coming aboard. In CAG 9 the LSOs were divided into four teams, so we had LSO duty every fourth day. On our LSO days, we would be on the LSO platform for anywhere from five to seven aircraft recoveries of 15 to 20 aircraft each, and as a rule we did not fly on those days. The other 3 days we would fly and the schedulers were pretty good about keeping us up with everyone else for flights since we missed every fourth day.

There was always one of the two air wing (CAG) LSOs plus five to six LSOs from the different squadrons for each recovery. We would take turns waving the recoveries, under the eye of the CAG LSO. Also one of us would be the writer, and record the aircraft number, wire caught, grade, and LSO comments for every landing. Following each recovery, we would journey to all of the squadron ready rooms and debrief the pilots who had just come aboard on their landing.

I loved being on the LSO platform! Just standing out in the raw elements, on beautifully sunny days or pitch black star filled nights, watching those awesome machines maneuver their way aboard was absolutely amazing. Unlike landing the Tomcat, being an LSO seemed to come very naturally to me. I quickly developed an eye for what the proper airspeed and glideslope looked like for the different aircraft of the air wing, and progressed rapidly as an LSO during our workups. It didn’t hurt to be training under our squadron LSO, who was one of the best in the air wing. One of the biggest benefits of my LSO training was the impact it was having on my own landing performance. I wasn’t close to ace of the air wing, but my own landing performance was definitely improving.

Putting on the final touches

A great deal of the flying off of the ship during workups involved simulated defense of the battle group, and in particular the carrier. We had prepared for this back at Miramar while completing Fleet Air Superiority Training (FAST), which was run by Topgun. It involved a series of classroom lectures and then a number of simulator sessions. This was the height of the Cold War and the training focused on defending the battle group against Soviet Bear, Badger, and Backfire bombers and all of the air to surface missiles (ASM’s) that they could carry. It also involved a great deal of electronic warfare and electronic countermeasures.

The simulator was the perfect place to practice these missions. Once we were on workups, we would practice the command and control while aircraft from the beach would fly out and simulate attacks on the battle group assets. As part of the the training for the smaller ships, we were at times tasked with flying missile profiles against them. One of these missions was particularly memorable for me.

We were flying directly at the ship from about 50 miles away, starting at about 45,000 feet and mach 1.4. Passing through about 35,000 feet, all of a sudden I was slammed to the right side of the cockpit and it sounded as if someone was beating on the canopy with a sledge hammer, a couple of times per second. It was pretty intense for about five to ten seconds and I slowly started reducing the throttles back out of afterburner. It turned out to be a compressor stall in the left engine, and once I got it out of burner, the stall cleared and everything returned to normal. We were able to continue the profile and make a low supersonic pass at the fantail of the target ship, to the delight of a large group of sailors jumping up and down and waving.

One other thing that I got to do prior to my first cruise was a live missile shoot. On virtually all of our training missions we would carry AIM-9 Sidewinder missile simulators. The Sidewinder was a close in heat seeking missile. The simulator was a Sidewinder, but it had no warhead and no rocket motor. Unlike shooting the gun, we did not go out and shoot air to air missiles on a regular basis because of their expense. However, new missiles were shot at times evaluating different areas of their envelopes, and old missiles were shot for aircrew training as they approached the end of their shelf life. That was the case for my shoot.

It was over water northwest of LA, and it was a shot at a drone. Fortunately we were able to locate the drone with the radar, lock it up, get a good missile tone, and take the shot. I never saw the target. It was very small and from about a mile and a quarter straight behind it, I would have needed binoculars to acquire it. Once I had the tone, I squeezed the trigger and instantly the missile departed the right pylon with an audible whoosh, and a trail of white smoke. It actually rolled the aircraft to the left momentarily. It was a non-warhead shot, so there was no explosion. We returned to Miramar and were told that the shot was a success, with the Sidewinder passing very close to the drone. The shoot wasn’t overly exciting, but it was good to know what to expect if I ever had to fire a missile in combat.

With workups complete, we were ready to depart on cruise. Our cruise schedule was like a seven and a half month vacation. On a regular piece of typing paper, double spaced, the ports of call filled the page. We would be in Pearl Harbor in just over a week. After that we would go to the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand before spending some time in the North Arabian Sea south of Iran. Since the Iran hostage crisis had begun, there had always been a US carrier in the North Arabian Sea. But the crisis had ended several years before our cruise, and the decision had been made that there would no longer be a US carrier continuously on station there.

We were to arrive there and relieve Midway, spend a couple of weeks on station, and then bolt for ports in Perth, Australia, Hobart, Tasmania, and Sydney, Australia. After that we would make our way back to the Philippines for a long Christmas stay, then on to Hong Kong, Korea, Hawaii and back to San Diego. It almost sounded like a luxury cruise! However, in the final few days before we departed, rumors were starting to spread about unrest in Nicaragua.

A sudden turn south

Ranger departed the pier at North Island early in the morning in mid July. All of the families at the pier waving goodbye knew something was up, but no one including those of us onboard knew exactly what it was. As soon as we got out to sea, things rapidly went south, literally and figuratively. The battle group turned left and headed for the coast of Nicaragua. On the second day out, a sailor on the flight deck was blown overboard, and his body was never recovered.

The next morning, we were awakened by the call of “General Quarters, General Quarters, all hands man your battle stations…this is not a drill.” It turned out that Ranger had been underway replenishing (UNREPing) with a supply ship, and had gotten too close to the supply ship. Once that happened, the venturi effect of the water passing between the hulls pulled the ships together, and the ships collided side to side. It was not a major collision, but did damage an aircraft elevator and do other damage to the starboard side of the ship, none of which would be repaired until we reached in the Philippines.

We proceeded on south to the coast of Nicaragua, and assumed a station. For about the next month, we remained there on station, primarily bringing dignitaries out from all of the Central America countries and putting on airshows to demonstrate the power of a carrier air wing. It was a miserable time onboard Ranger.

The ship was supposed to be in the shipyard undergoing rework. However, the decision had been made to delay the rework and send it on another cruise. Ranger couldn’t make enough fresh water, so water was continuously being rationed. Just about the time you got all soaped up in the shower, the water, perfumed with a hint of jet fuel, would cut off. As a result, I always filled a five gallon bucket with water before I started soaping up, so I would have water for rinsing. Also, in the warm coastal Pacific waters, the engineering department couldn’t keep the ship cooled down. Our squadron had a 110 man bunk room for a large portion of the enlisted men. By 0100 to 0200 every morning, when the majority were trying to sleep, the room would be over 100 degrees. Most got very little sleep. As the First Lieutenant Officer I did everything I could do to make the situation bearable, but it was a losing battle.

Finally, President Reagan’s “Gunboat Diplomacy,” as Newsweek called it, was over and we headed west for Pearl Harbor. Soon we reached the cooler waters of the Pacific and the ship began to cool down. We arrived at Pearl a day or two short of our first “Beer Day” (45 days at sea without a port). It was a beautiful morning, just after sunrise, and manning the rails in summer whites was a sobering experience as we silently glided past the USS Arizona Memorial to our pier.

Pushing west

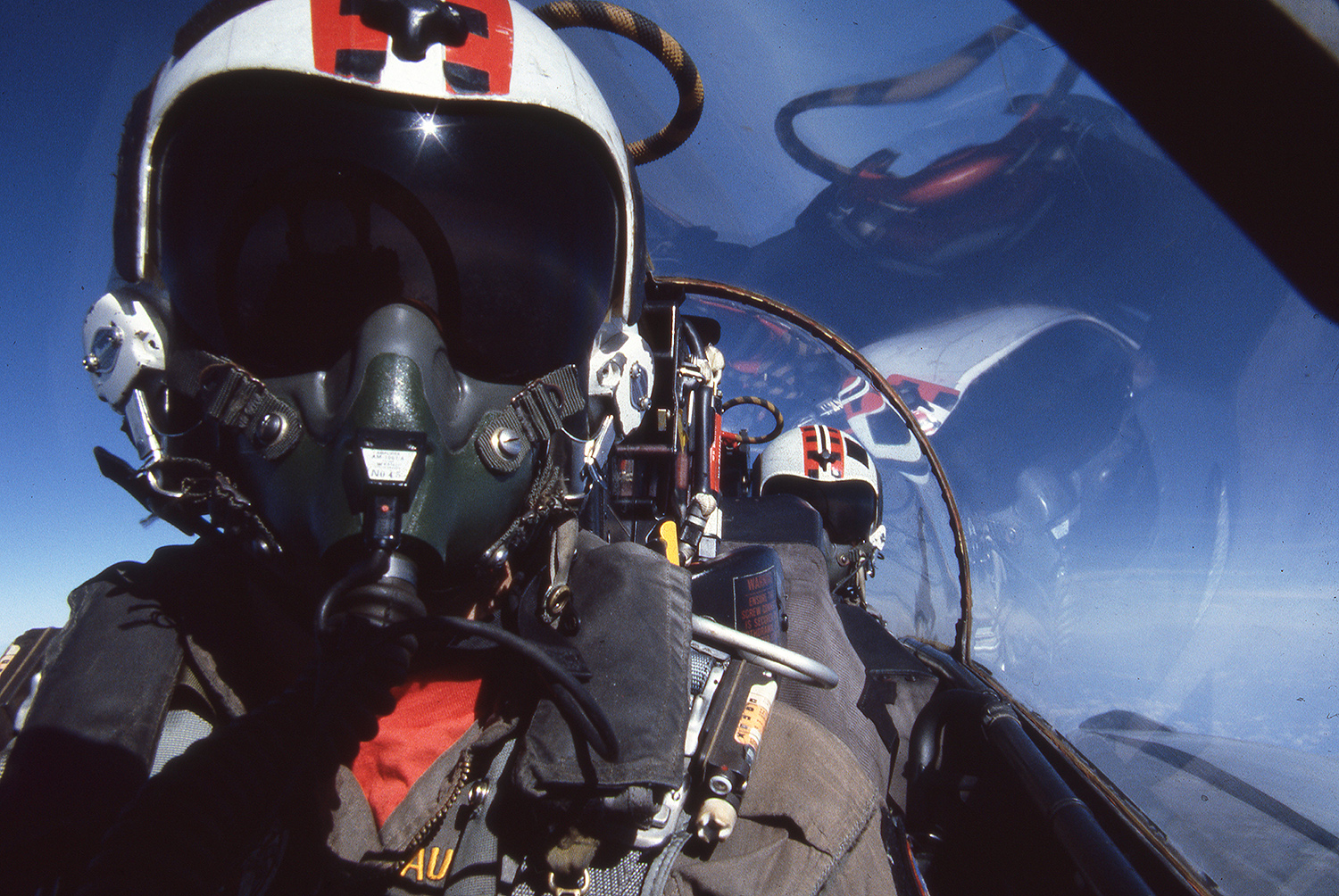

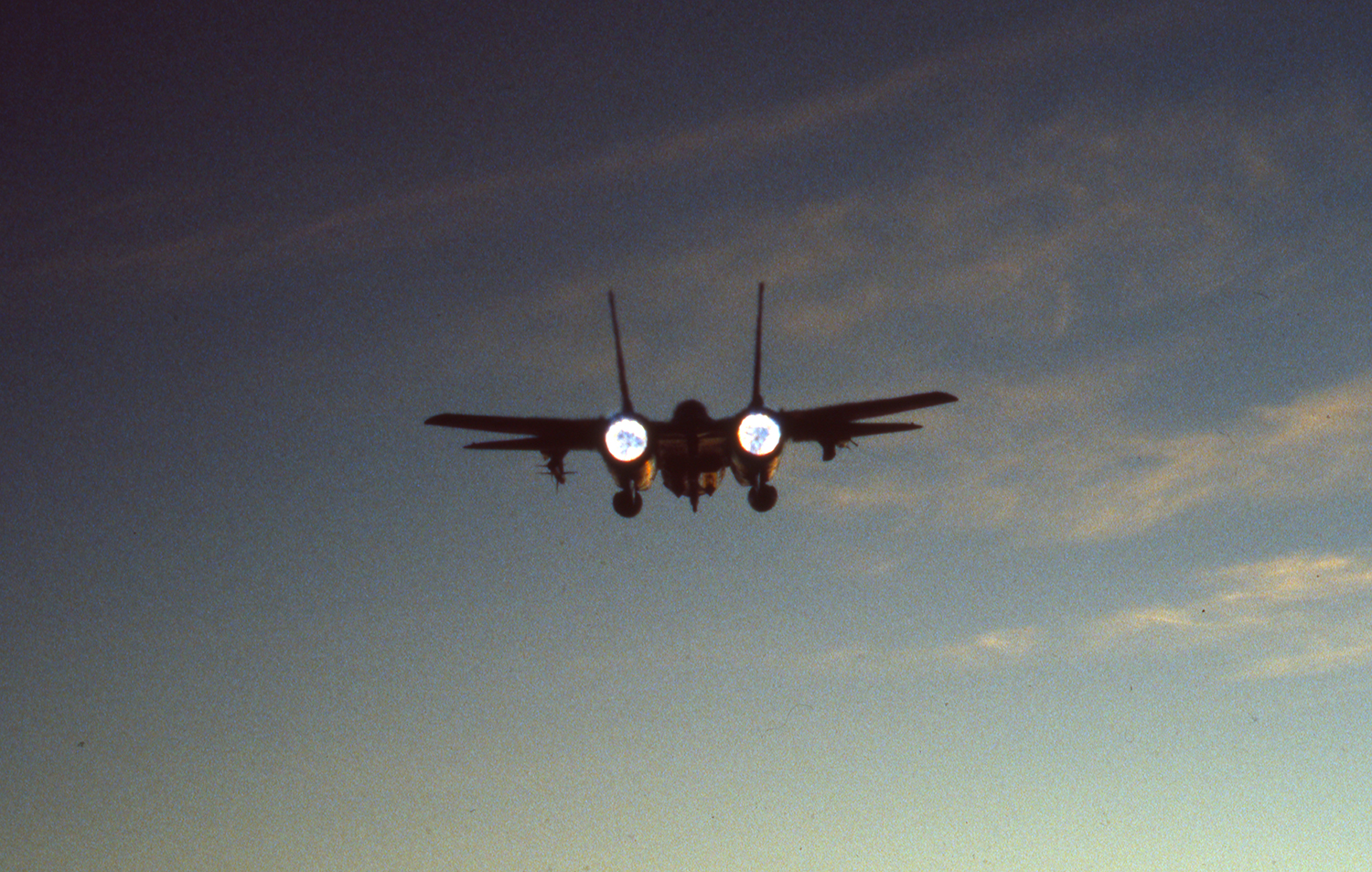

After a quick liberty in Honolulu, we were westbound in the Pacific, and well behind schedule. Flight ops on a carrier require the ship to turn into the wind, which may require the ship to turn 180 degrees and go opposite the direction it’s trying progress. As a result, while we headed for the Philippine Islands (PI), flight operations were limited. However, once west of Hawaii, the Tomcat squadrons began manning alerts any time flight operations were not being conducted.

Normal alert duty lasted for four hours. Initially you would suit up in flight gear and remain in the ready room or wardroom for the first two hours on Alert 15, meaning you had 15 minutes to be airborne. After the first two hours, you would man up the Alert 5 aircraft and sit in it for the next two hours. The Alert 5 aircraft would be parked near a catapult and was required to be airborne within five minutes after the launch was called. It was very easy to doze off while sitting in the alert aircraft with your helmet on and visor down. All of a sudden the plane captain would start beating on the side of the aircraft to signal that they were launching the alert. The race was on between your aircraft and the other Tomcat squadron’s aircraft.

Lowering the canopy, starting engines, getting a final inertial navigation position, breaking down the chains and chocks and taxiing to the catapult were all done within three to four minutes. Five minutes after the first startling bang on the jet, you were hurling off the the catapult and accelerating on a hot vector for an unknown target. Talking about a rush, dreams to a cat shot in five minutes, it can’t get any better than that! Usually you had no idea why you were being launched. Sometimes it was to ID a ship, but often it was to intercept aircraft including Soviet Bear and Badger bombers. Usually they would be intercepted hundreds of miles from the battle group and escorted continuously until far from the carrier and departing the area.

We slipped into port at Subic Bay, Philippines during the night. Probably before I had awaken, the Filipino workers had boarded and started attacking the mangled metal from our collision on the starboard side of the ship. We spent two weeks there, operating from Cubi Point Naval Air Station. The flying included work with the Air Force from Clark Air Force Base, and also doing night FCLP at Cubi Point to maintain landing currency.

Leaving the PI we were still well behind schedule, so our ports in Singapore and Thailand were cancelled, and we proceeded directly to the North Arabian Sea. The Midway was not allowed south of a certain latitude until we were north of it.

On station in the Middle East

We were now the on duty carrier in the North Arabian Sea. We spent the next several weeks flying a very full flight schedule. Because of all of the time we would have in ports in the latter part of the fourth quarter of the year, we had a lot of fuel money to burn now. Most of the flying involved escorting Iranian aircraft and checking out/photographing all of the ships transiting the area. Occasionally the Soviets would come out and checks us out, providing some higher profile escort missions.

We also did several days of overland work with the Omani Air Force, flying Hawker Hunters and Jaguars. The pilots were British, they knew the country like the back of their hand, and they loved to fly low. No matter how low you flew, they were always below you, regardless of whether you were on level terrain, or in the canyons. It was a blast working with them.

On about October 21st, 1983 we said goodbye to the North Arabian sea, and started steaming southeast for Perth, Australia. October 23rd was a no fly day. We were in an All Officers Meeting (AOM) in the ready room when all of a sudden the ship started healing heavily, which meant we were turning hard. Immediately heads started turning, all of us looking at each other and shaking our heads. Everyone knew that something was up. Within 5 minutes, the captain came on the 1MC (ships PA system) and informed the crew that the Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon had just been bombed, and we had been ordered back to the North Arabian Sea—this time indefinitely.

It’s worth mentioning that communications in the early ’80s was nothing compared to what it is today. There were no internet, no email, no cell phones, and no personal computers. The turnaround on normal mail back to the states was about a month. If you asked a question of family back home, a month or so later you might have a reply. In port, you were able to make international long distance calls, but they were very expensive. In the PI, there was a small building full of phone booths that you would go into. You would give the clerk the phone number and then be sent to a booth. Eventually the phone would ring, and when you picked it up, you would be connected. Also there was no CNN and very limited news from back home. Consequently, we had very little idea of what was actually going on in the world. As soon as we left on cruise, we started doing contingency strike planning for the different areas of the world that we would be near. So over time, with the lack of outside information coming in, and the constant preparation for combat, you pretty much felt like you were on the brink of war. And at that point during the Cold War, any war could rapidly lead to World War III.

We quickly returned to the North Arabian Sea. Since it was generally believed that the barracks bombing had been instigated by Iran, contingency planning for strikes into Iran began in earnest. We started to fly rehearsals of entire strike missions, but all done over water as opposed to over land. On November 1st, we had another general quarters which was not a drill. A fire had broken out in the number four main machine room, and fire fighting went on for hours. Finally the fire was extinguished, but six sailors died and 35 were injured in the battle. This seven and a half month “vacation cruise” had very rapidly becoming a pretty dismal affair.

Eventually things settled back down to the normal North Arabian Sea ops. However, there was no end in sight. Soon the remainder of out port schedule began to fall apart. There was no relief carrier in sight, and after the barracks bombing, there was no way that the North Arabian Sea would be left without a carrier for the foreseeable future. Because our schedule had provided so many days in port, we had used up most of our fuel allocation early in the quarter. Now that the ports were rapidly going away, we were short on fuel money to fly, as were all of the squadrons in the air wing. The end result was that there were more no-fly days, and on the fly days the majority of the schedule was night flying so that pilots could maintain their night carrier landing currency of one night landing every seven days.

One bright spot was “beer day!” Normally there was no alcohol on the ship, however if you went 45 days without a port, the ship had a beer day. Obviously it was a no-fly day! Everyone on the ship could have two beers, provided by the supply department. Another bright spot for the aircrew was flying. At least we got to leave the ship for a couple of hours when we flew. The poor non-aircrew never got away from it.

The second “Beer Day” wasn’t as bright, as we had now been at sea for 90 days with no ports. In fact it was getting pretty depressing. Finally sometime after Christmas, rumors started circulating that the Midway was coming back to relieve us, and eventually those rumors came true. If we had been allowed to depart the North Arabian Sea a few days earlier, we would have been able to stop in Thailand or Singapore for a port call, but the powers that be would not let us transit south of that magic line of latitude until the Midway was north of it.

Homeward bound

Standing on the flight deck as we passed Singapore for the second time this cruise without stopping, we at least could see the city and waved. The next morning we made a short detour south to cross the equator and then headed back to the north. With an all morning ceremony, those of us who had remained disgusting pollywogs for the entire cruise, were finally initiated into the ranks of the trusty shellbacks.

We made a brief stop in the PI, and then headed east for Pearl Harbor. We flew enough to remain night current, but kept the ship moving east as quickly as possible. Approaching Hawaii, we were finally able to stand down the alert 5/15 watches. In Hawaii we picked up the Tigers, family members who were allowed to ride the ship back to San Diego, based upon available space.

I was fortunate enough to have my dad along for the week. He was a Navy veteran of World War II, as a B-24 Liberator radioman in the Pacific theater. In his 4 years in the Navy, he had been on a ship once, transiting from San Diego to Hawaii. This Tiger Cruise allowed him to finally complete his round trip back to San Diego.

There was plenty to keep the Tigers busy during the week of sailing to San Diego. The air wing conducted an airshow just like the ones that had been conducted off the coast of Nicaragua early in the cruise. Also there were tours of all of the different parts of the ship. The day before Ranger arrived in San Diego, the air wing squadrons flew off to their respective Naval Air Stations. After a full squadron flyby at Miramar, we came back into the break in sections and got our first non arrested landing in a long time. What a tremendous feeling it was to finally be back home.

The next morning we were at the pier at NAS North Island as Ranger docked, and the ships company and Tigers came ashore. Concerning that full page port schedule we had received before we departed on cruise, two things happened as planned. We departed on cruise as scheduled, and seven and a half months later we returned as scheduled. Nothing else between those dates happened as scheduled, and most of the ports didn’t happen at all. But cruise was over—I had survived!

Fighter Derby

The turn around began. Veteran crews began to leave the squadron for shore duty, and newly trained crews began to arrive from the RAG. Shortly after our return, I was informed that two crews had been selected by the CO and Ops Officer to attend the Topgun Power Projection Course, and I would be one of the pilots. I had seen the difference that the course had made in the previous turn around’s Topgun graduates, and now that I was very comfortable in the Tomcat, I was up for the challenge. It was a dream come true!

After graduating from Topgun early in the turnaround, the remainder of the 15 month period went very much like my first VF-24 turnaround. Another Red Flag, another gun det (this time to NAF El Centro), another NAS Fallon det, and a det to MCAS Yuma for Fighter Air Readiness Program (FARP) and the Fighter Derby were all a part of it.

Fighter Derby was a competition between all west coast F-14 squadrons for a year period of time. Each squadron would deploy to Yuma at some time during the year and fly their missions on the instrumented range east of Yuma. All of the missions were two F-14’s against four Topgun adversary aircraft plus a wildcard aircraft attempting to sneak in from behind during the intercept.

VF-24 had prepared extensively for Fighter Derby and developed tactics based upon the airspace, the threat, and their expected tactics. I was the section lead for one of our first sections to compete. We started the intercept accelerating to about Mach 1.1. The RIOs did a great job with the intercept, detecting the pincer tactic and spotting the wildcard attempting to sneak in from behind. With forward quarter shots, we took out the two lead bogies, blew through the trailers and flew to the southeast corner of the range. Decelerating, we cross turned back into the remaining bogies chasing us, and tried to reacquire them with radar and visually. Naturally the tiny bogies had no problem visually keeping track of the F-14s, known by adversary pilots as the “aluminum overcast” due to their size.

We immediately began to accelerate, and when we did reacquire the bogies, one was rolling in on our aircraft, and one on our wingman. We both started to turn defensively, but the way the geometry worked out, I was able to shoot the bogie off of my wingman, and shortly after that, he was able to kill the bogie that was attacking me. We immediately bugged out to the west and moments later, a “knock it off” was called.

Shortly after that my RIO asked, “what happened?” I was never quite sure if he didn’t understand why the knock it off had been called, or if I had put him to sleep with the Gs somewhere along the way and he was just waking up. I laughed for a long time over that.

We proceeded back to Yuma, landed, and downed both aircraft for over-stress inspections. Our section got a perfect score for our engagement; four bogie kills, no fighter kills, and detecting the wildcard. A number of other Renegade sections did the same, and all did well. Our tactical game plan had worked. Eventually we learned that the Fighting Renegades were the 1984 Fighter Derby champs!

More engine surprises

In October of 1984 we manned up for an afternoon flight in the warning area off of San Diego. I don’t remember exactly what our mission was, but we were the flight lead for a section of Tomcats.

We were taking off from the shorter Runway 24 Left at Miramar. In VF-24 we did not do section takeoffs, where both aircraft rolled down the runway together in a tight formation. The wingman normally waited about 10 seconds after the lead started rolling, before commencing his roll. I was centered halfway between the left edge of the runway and the centerline, and my wingman was on the right half. I was in minimum burner, and as I hit about 135 knots and was starting to ease back on the stick, there was a huge boom from my right side, and the aircraft immediately started to pull right. I countered with left rudder and kept it on my half of the runway as I slowly continued to rotate the aircraft.

Slowly lifting off, I added more burner and carefully monitored the angle of attack gauge, keeping it below 14 units. Early in the life of the F-14, aircraft had been lost because of getting to a higher angle of attack with the large thrust asymmetry associated with an engine failure. Another problem in the early F-14 days was an uncontained catastrophic engine failure where the aircraft was damaged so badly by the engine coming apart, that the crews had to eject. Fortunately for us, each engine was now were encased in a 1,000 pound titanium sleeve to contain engine failures.

The one other thing that had been added to the aircraft to try to prevent flat spins was an engine stall warning system. It consisted of flashing amber lights up on the sides of the windscreen, and an aural annunciation of something to the effect of “right engine stall” repeatedly. The aural annunciation began immediately after the boom, and would not stop! Intercom communication between myself and my RIO, and radio communications with air traffic control (ATC) were almost impossible for me to hear.

Our wingman joined up as I flew the departure and limped the jet out over the water. Eventually we got our volumes up and were able to hear each other and also ATC over the stall warnings. We circled back to the east and flew a single engine approach to Miramar. After taxiing back to our ramp and shutting the remaining engine down, we got out and looked into the right engine burner can. It was full of mangled turbine blades. My biggest regret was that I didn’t grab a few blades as souvenirs. After our wingman returned to land, we debriefed our short flight. They informed us that when the engine blew, there was a huge cloud of smoke that temporarily obscured our jet on the takeoff roll. I had survived another close call but not the closest.

Distractions

We were now approaching our next cruise on USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63). The ops tempo was picking up rapidly with workup at sea periods. I had just been given good news/bad news by my CO. My three year sea tour in VF-24 was just about over, and the detailer had notified my skipper that I could have orders to Topgun as an instructor having completed the course as a student just months prior. Unfortunately, my CO had informed the detailer that he needed to extend my time in VF-24 for the duration of the Kitty Hawk cruise, because our other squadron landing signal officer was leaving the Navy for the airlines. They call it “needs of the Navy.”

There was no guarantee that I would still get orders to Topgun when the cruise was over. I was disappointed, but if I wasn’t going to be at Topgun, there was no place better to be than VF-24. I was now in a leadership position there as the Pilot Training Officer and Squadron LSO, and life was very good. There was one significant distraction as we prepared for deployment.

Shortly after we returned from the Ranger cruise, we had used money from our coffee mess to completely rework our squadron ready room in the hangar. When Hollywood decided to film a movie about Topgun, they started scouting out shoot locations, and they chose our ready room to film the opening classroom scene. So in the midst of working long days and then doing FCLP at night, Hollywood invaded our squadron spaces for about a week. With huge spotlights shining in the windows from outside, and a smoky haze being pumped from machines into the room, Tom Cruise, Anthony Edwards, Val Kilmer, and the rest of the cast repeatedly filmed their scenes, and between shoots, wandered around our spaces. It was definitely interesting to witness, but unfortunately we were almost too busy to take it all in.

Final hurrah with the Fighting Renegades

We departed on cruise on schedule, and Kitty Hawk was a much better ship from which to operate. It was significantly larger, and the flight deck arrangement made operations much easier than on Ranger. Besides Hawaii and the PI, we had two additional ports on this cruise; Mombasa, Kenya and Columbo, Shri Lanka. Neither was high on our list of places that we wanted to go, but both were better than nothing, and we made the best of them!

Fortunately this cruise had no beer days. As we transited back through the PI on our way home, we had our final Foc’sle Follies where carrier landing awards were passed out. The VF-24 Fighting Renegades won the Top Hook award as a squadron for the best landing grades of the cruise. One of our department heads took the individual Top Hook award for the entire cruise. I was awarded three Top 10 patches for being in the top 10 pilots in the air wing for two of three line periods, and for the entire cruise. Finally, I felt vindicated for my landing struggles in the RAG. It had been a long and painful process, but I had learned lessons that I would use and pass to others for the rest of my aviation career. I also received word that I would be receiving orders to Topgun upon my return to Miramar.

Leaving VF-24 was bittersweet. It was probably the most exciting and fun time of my life. Being a young junior officer (JO) flying a Tomcat around Miramar, the USA, and on and off of an aircraft carrier was just about unbeatable. The morale of the squadron itself was without a doubt the best. We had a tremendous group of mostly bachelor JOs, and the few wives that we had could hang with them. Our senior officers were JOs at heart. No matter the situation, we found the humor. The activities that we planned, the skits that we came up with, the videos that we made, all were absolutely hilarious. You know that you’re in the right place, when the JOs from your sister squadron want to come to your squadron activities and parties.

VF-24 had been the time of my life, but it was now time to move on.

Make sure to read part one of the Paul Nickell series where we follow Paul as a Topgun instructor flying the legendary F-16N and part two where Paul details his time as a student at Topgun battling A-4s and F-5s.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com