While unmanned aircraft have become synonymous with America’s way of war since 9/11, they’ve actually been an important feature of military aviation for the better part of a century. In the early years of the Cold War, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) turned two of Avro Lancasters in unique training aircraft, able launch and control jet-powered target drones rather than bombs.

In March 2017, the San Diego Air and Space Museum posted a series of videos online showing these specialized Lancaster B Mk 10DCs in action. The museum’s archive had digitized the footage from a collection of films the Ryan Aeronautical Company donated in the 1990s.

In 1951, American plane-maker Ryan began building the portly Firebee unmanned aircraft for the U.S. Air Force, Navy and Army. Canada was among the first foreign customers.

The pilotless planes were ideal training tools. With a top speed of over 500 miles per hour and a wing span of just 11 feet, the drones were more agile and challenging for pilots and gunners than many towed targets, which were limited by the characteristics of the tug aircraft.

Since they weren’t physically attached to the controlling aircraft, the Firebees made things safer for everyone involved, too. Trainees could shoot live rounds at the drones without worrying about accidentally shooting down another plane.

Crews could recover the unmanned aircraft even if they suffered significant damage. The flying targets had a two-stage parachute system that would deploy if the engine failed or the radio signal with the control station cut out. The individual controlling the Firebee could also trigger this sequence manually.

The Firebee wasn’t without its own faults. The aircraft could only stay aloft for around 50 minutes at a time. In addition, the range of the radio link was limited, meaning the drones had to stay relatively close to the control station.

The U.S. Army launched its versions from the ground using an expendable rocket booster. This worked fine for low-altitude training exercises for anti-aircraft crews.

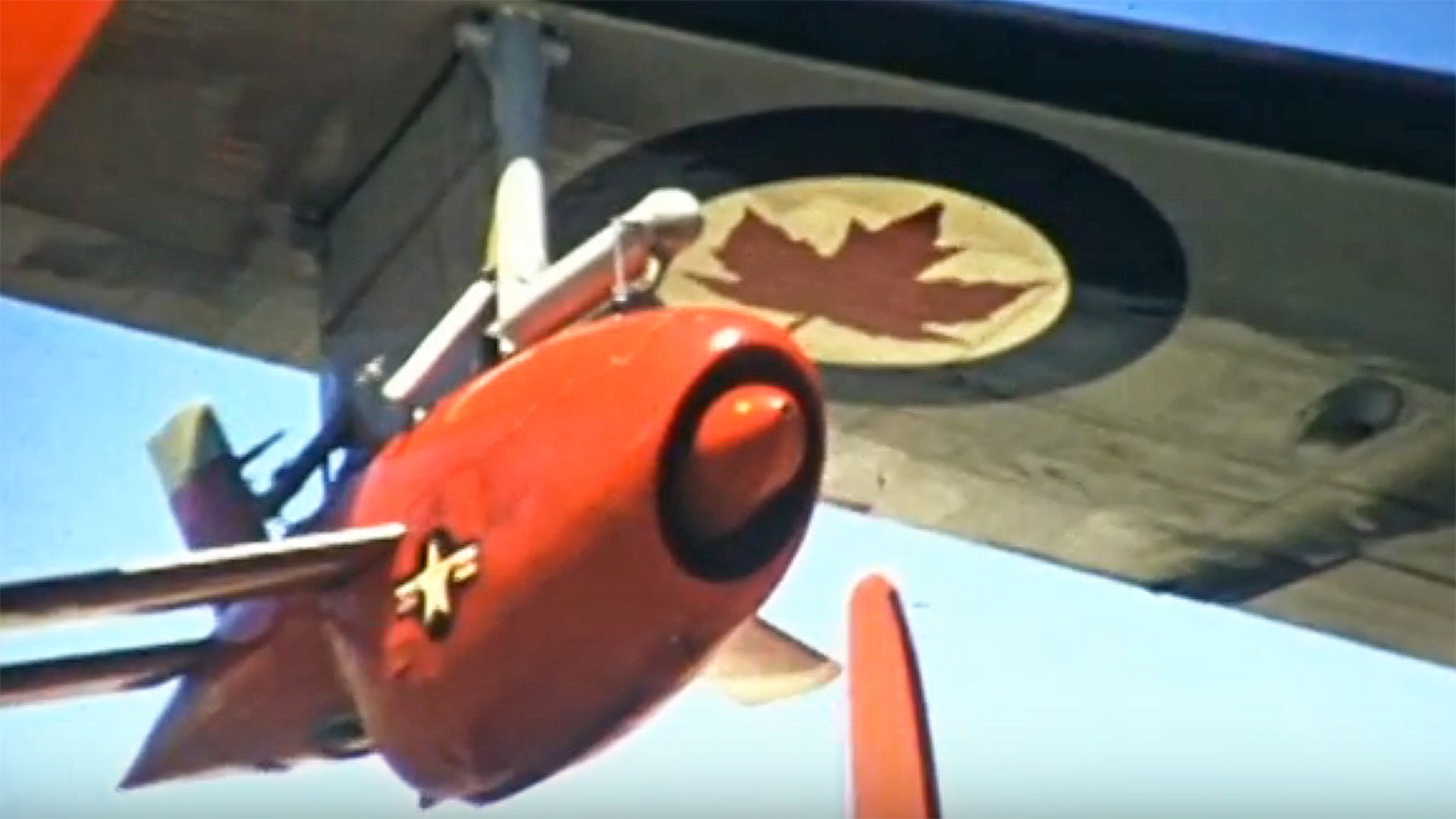

For training higher-flying fighter pilots, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy launched their variants in mid-air from modified twin-engine Douglas B-26 Invader attack planes and Lockheed P2V Neptune patrol aircraft. The RCAF took a similar approach with the modified Lancasters. The four-engine planes were each capable of carrying two drones, one under each wing.

The iconic World War II bomber would have made sense since it both had the payload to carry the Firebees and was readily available. During World War II, Canadian company Victory Aircraft Limited produced 430 B Mk 10s for service with RCAF units under the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command.

Able to carry 14,000 pounds of bombs, the Lancaster series was a key component of the RAF’s bombing campaign in Europe. Special versions could carry the 22,000 pound Grand Slam bomb, which were supposed to break through reinforced structures like submarine pens, and unique “bouncing bombs” as part of a daring, top secret plan to attack dams in Germany and cause catastrophic flooding.

After the war ended, many of these planes made their way back home and ended up in new roles, like as drone motherships. With bright orange noses, wing tips, and tails over a natural metal finish, the B Mk 10DCs soldiered on well into the 1950s.

Fighter pilots in Canadair Sabre, Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck, and McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo jet fighters could have squared off against the Firebees. Canadian forces might have also tested early surface-to-air missiles against the drones.

In the early 1960s, the RCAF retired the last of its Lancasters, still in service as maritime patrol planes and search and rescue aircraft, with its own fleet of Neptunes. Ryan continued to upgrade the Firebee family, building improved targets, unmanned spies, and experimental pilotless attackers, primarily for the U.S. military.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com