After more than a decade, the U.S. Navy is still making slow but steady progress on its futuristic railgun. If the program can produce a functional and cost efficient weapon, it could give the service’s ships a deadly new way of attacking enemy vessels and forces ashore, as well as defending against aircraft and fast-flying missiles.

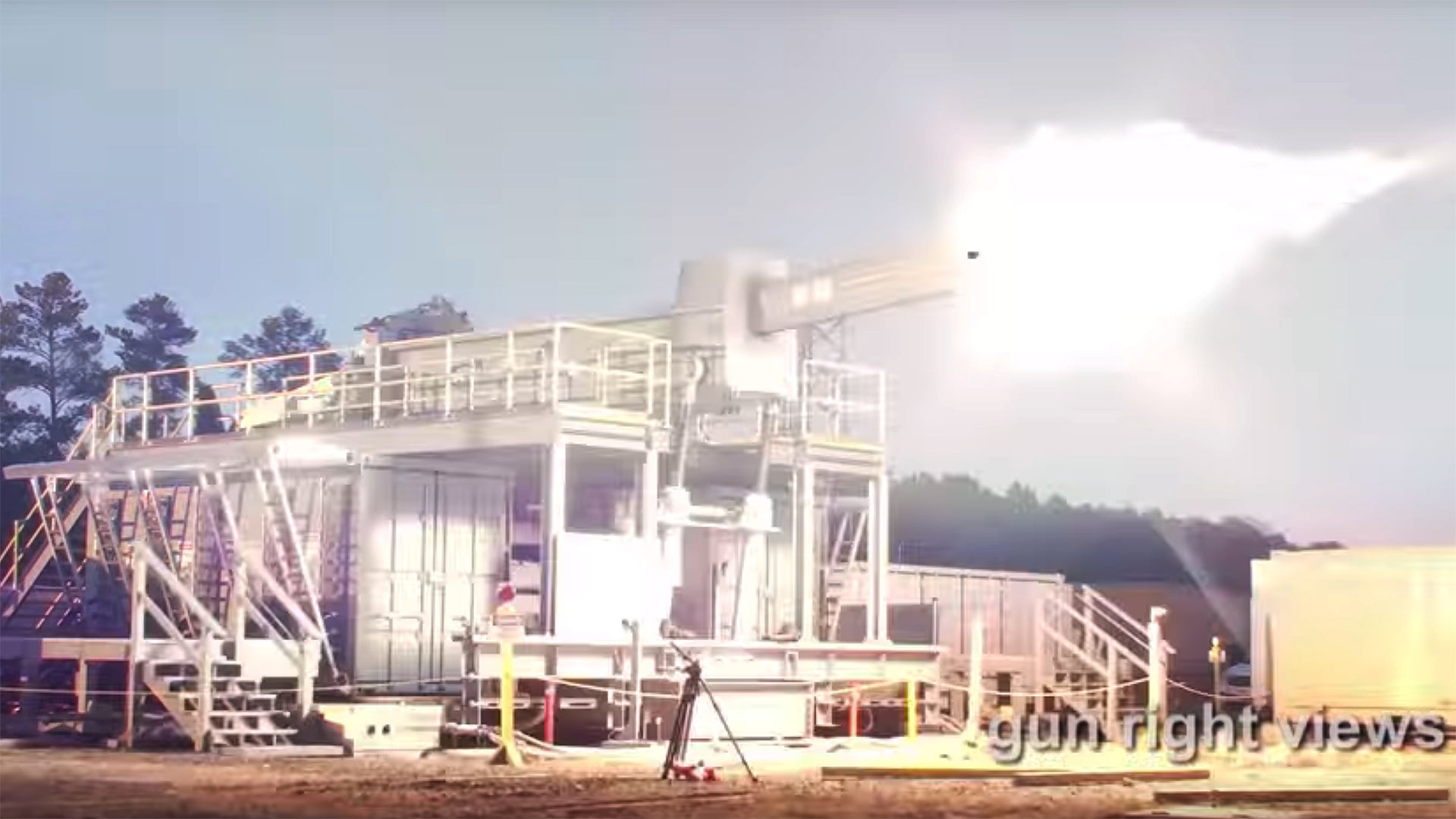

On March 21, 2017, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) posted an official video showing a test of defense contractor BAE’s electromagnetic cannon at Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahlgren Division in Virginia. The experiment had taken place a little over four months earlier. The Navy program is also working with a second model from General Atomics, better known as the company behind the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper drones.

The latest footage did not include any new details about the experimental weapon’s capabilities. According to the official fact sheet, the prototypes use high electric currents to create powerful magnetic fields, squirting out solid projectiles at speeds over 4,500 miles per hour, roughly six times the speed of sound.

“Navy planners are targeting a 100+ nautical mile initial capability,” the Office of Naval Research’s website explains. “A variety of new and existing naval platforms are being studied for integration of a future tactical railgun system.”

The Navy has been working on the project since 2005. Phase II, which would hopefully move the program from a technology demonstration closer to a plan to buy actual weapons, kicked off in 2012.

One of the consistent goals has been to fit these hyper-velocity weapons on its new Zumwalt-class destroyers. Full of electronics and equipped with a hybrid-electric propulsion system, these stealthy ships seem like a logical choice for the new weapons and their significant power requirements.

In addition, the electromagnetic guns could replace the warship’s disappointing 155 mm Advanced Gun System. In 2016, Navy officials admitted they were no longer planning to buy Long-Range Land Attack Projectiles (LRLAP) for the Zumwalt and her sister ships.

Along with these GPS-guided shells, each with a price tag of $800,000, the howitzers were supposed to be a key feature of the new ships and one of the most important components of their main armament. Without the ammunition, there have been serious questions about how useful the guns will be when the destroyers make their first patrols.

Less expensive existing guided cannon rounds, rocket artillery, or just more vertical-launch missile cells are all possible near-term substitutes for the LRLAP. If it works, the railgun could make the artillery systems obsolete entirely, since it would have the range and speed to provide fire support for friendly troops and take out incoming missiles.

The latter point is especially important as Russia and China steadily improve and expand their anti-ship and cruise-missile arsenals. Both countries are interested in selling only slightly less capable models on the international market and Iran and North Korea have been eager to develop their own comparable systems to challenge America’s maritime power.

Inert projectiles and the lack of propelling charges make the railgun a safer and more economical alternative to traditional gun systems in many ways, as well. A ship with one of these weapons doesn’t have to allot any space to explosive propellants or risk ammunition stores exploding in combat.

“Our need to carry gunpowder with us is a big vulnerability to our ships,” Robert Freeman, an ONR spokesman, told U.S. News and World Report in 2016. “A railgun could eliminate that need.”

But while the Navy and its industry partners have successfully shot the experimental versions on land, they have yet to test the weapons at sea. In 2016, the service pushed off plans to evaluate the cannon’s performance on board an Expeditionary Fast Transport, previously known as the Joint High Speed Vessel. In the past, these twin-hull catamaran ships have helped test out other systems, including drones and aerostats, in maritime environments. In 2014, one of these ships, the USNS Millinocket did bring the railgun prototypes to Naval Base San Diego for a static display. The ship was not set up to shoot the weapons.

The official reasoning for the delay was that preparations for a demonstration for the sake of demonstrating could slow down the overall project. “I would rather get an operational unit out there faster than do a demonstration that just does a demonstration,” Navy Admiral Pete Fanta, then the director of surface warfare and now the head of warfare integration, told Defense News in 2016.

However, there were reports of continuing concerns about powering the weapon, adequately cooling it down, and just finding space in any candidate ship for the complex equipment. Earlier in March 2017, General Atomics proudly announced it had built a new high-energy pulsed-power container (HEPPC) for its railgun variant, which had twice the “energy density” as the previous model. This smaller unit took up an entire 10-foot shipping container.

To try and further speed up development, the Navy had also spun off work on the actual projectile from the main program. Theoretically, engineers could make this “high-velocity projectile” (HVP) work with standard 5-inch guns on ships like the Arleigh Burke-class destroyers and in Army and Marine towed and self-propelled 155mm howitzers such as the M777 and M109A6 Paladin.

Traditional chemical explosives could still boost these projectiles up to speeds of Mach 3. Armed with these rounds, ground artillery units might be able to defend against aerial threats, smaller incoming missiles and rockets and other targets they don’t have the range or speed to hit with regular ammunition. The major limiting factor would be whether existing barrels could take the punishment of firing the super-fast projectiles and for how long.

The Army itself is interested in possibly replacing conventional tube artillery with railguns and their “unlimited magazines” at some point in the future. In April 2016, it test fired a prototype system from the back of a trailer during a demonstration at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, home of the service’s artillery school.

In spite of these developments, the Navy hasn’t changed its timeline for when the electrically-powered cannons will be operational since at least 2015, according to a March 2017 report from the Congressional Research Service. The service still reportedly expects the guns to be in action by 2025. The potential for more difficulties – old or new – has not been lost on members of Congress, many of whom are looking to expand the defense budget, but have no interest in programs that might never produce results.

“Although the Navy in recent years has made considerable progress, a number of significant development challenges remain,” CRS noted in its review. “Overcoming these challenges will likely require years of additional development work, and ultimate success in overcoming them is not guaranteed.”

For Fiscal Year 2017, the Navy asked for more than $23 million to continue work on the railgun program. It remains to be seen whether legislators will match or increase this funding in the next budget cycle.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com