U.S. Air Force security forces, as well as other military personnel and federal law enforcement agencies, may soon be getting a new tool to take down small commercial drones: shotgun shells with a net. The special cartridge is just one system the Pentagon has been looking at to manage the growing threat from small and readily available quad-and hex-copter-type unmanned aircraft.

On Jan. 31, 2017, the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) announced plans to buy and evaluate 600 12 gauge SkyNet Mi-5 shells from AMTEC Less Lethal Systems (ALS). If the Air Force was happy with the tests’ results, the service would have the option of buying another 6,400 rounds.

According to a so-called ”justification and approval” document, the Pentagon’s Joint Rapid Acquisition Cell (JRAC) put the urgent request together in response to the potential danger the certain small flying machines posed “vital national security assets,” a phrase that commonly refers to nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. Government censors removed mention of the specific command that asked for the gear and its area of responsibility.

Any federal agency has to submit one of these formal justifications for any contract it wishes to award “sole source” to a specific company without a long and drawn out competition. AFLCMC subsequently took over the actual purchase process.

“The current technology set of net projectiles is a very immature market,” the contract review explained. “The Skynet Net Gun system has been demonstrated at several locations in varying conditions during testing as part of the 2016 Air Force Research Laboratory Commander’s Challenge.”

Groups from around the Air Force and private contractors demonstrated various prototype and production systems during this event, which had the Latin motto in caleo exitium para – roughly translating to “prepare for hot destruction.” A team from Lackland Air Force Base went so far as to use a small wheeled drone to try and snag a quadcopter on the ground with a large net.

“The most recent testing of the Skynet round occurred at Department of Energy Range 25 in Las Vegas, [New Mexico] in December 2016,” the justification report added.

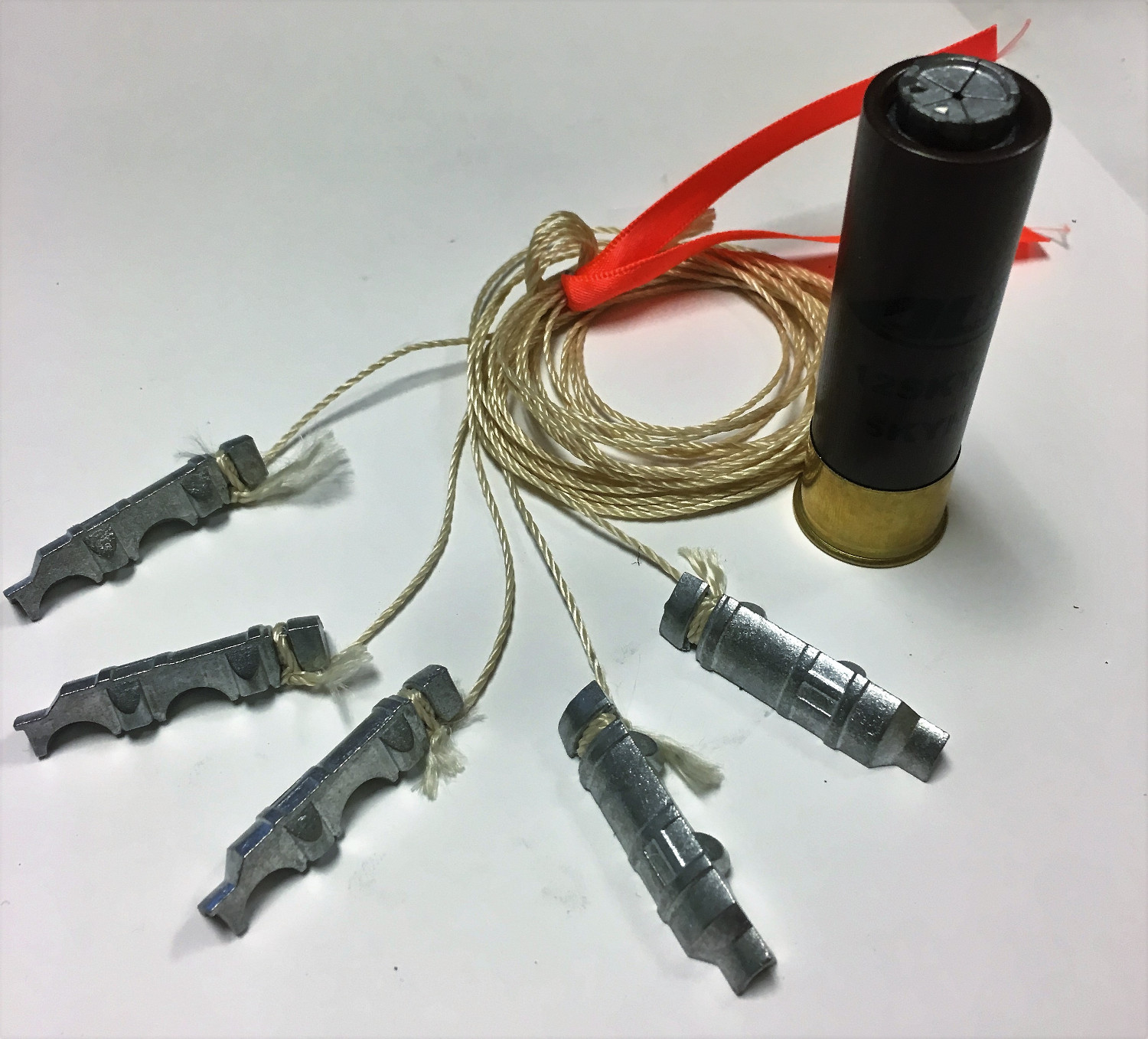

Compared to other dedicated anti-drone weapons, the SkyNet Mi-5 is relatively simple. Each shell contains five metal segments, each connected by a high-strength cord to a central point. “The five tethered segments separate with centrifugal force and create a five foot wide ‘capture net’ to effectively trap the drone’s propellers causing it to fail,” ALS says on its website.

The Air Force said it will fire the projectiles from its standard Remington Model 870 shotguns. For the cartridge to work properly, Airmen will need to install “choke tube” with rifling to the gun’s muzzle to get SkyNet spinning. The contract options also included a possibility of purchasing 100 of these add-on devices.

The Pentagon only wants the weapons to be able to handle remote-controlled aircraft in what it describes as Categories 1 and 2. The first group covers unmanned airplanes weighing less than 20 pounds and able to fly no more than 1,200 feet high. The second level includes drones between 20 and 55 pounds with the ability to reach altitudes of up to 3,500 feet. Drones in both categories generally wouldn’t be able to fly faster than 300 miles per hour.

In addition to SkyNet, there has been steady work across the Pentagon on other equipment to battle the tiny unmanned aircraft, ranging from hand-held and vehicle-mounted jammers to fast-firing chain guns to lasers. Unfortunately, the Pentagon appears to be generally relying on ad hoc urgent contracts to purchase these systems in lieu of a more comprehensive, long-term approach.

The Air Force posted the actual justification document on FedBizOps, the federal government’s main contracting website, just one day after Air Force Gen. John Hyten, head of U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), told members of Congress that the Pentagon was still dragging its feet in setting up defenses against small unmanned aircraft broadly. “We’re going too slow,” Hyten declared on March 8, 2017.

“We have to get the right policies and authorities out there so our defenders know exactly what to do, and then we have to give them material solutions to allow them to react when they see a threat and identify that there is a threat so they do they right things,” the officer in charge of America’s nuclear deterrent continued. “It’s not enough for me to tell our guys to take a shotgun and shoot down something.”

There may also be concerns that projectiles might miss a drone and come down somewhere else, causing inadvertent damage or even casualties. This would be an especially serious concern for troops at sites situated near civilian communities. He went on to explain that his forces needed clear legal guidelines to go along with any new equipment, something civil aviation authorities have also struggled to develop in the face of rapidly improving technology.

Quadcopters and other tiny pilotless aircraft pose real dangers to both first responders and military personnel at home and abroad right now. In June 2016, firefighting helicopters battling a wild blaze in California had to briefly halt operations after a private drone entered the airspace. Four months earlier, U.S. Navy security personnel had spotted a small drone over the Kitsap-Bangor base, which is home to a number of nuclear-armed Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines.

More recently, Islamic State modified commercial unmanned systems so they could drop small bombs on government troops and civilians in Iraq and Syria. In January 2017, the terrorists released a video of them using the improvised arrangement to attack an Iraqi M1 Abrams tank. Potentially even more worrisome, the brutal group has used the drones to spy on their opponents, help artillery units adjust their fire and even film slick propaganda videos of suicide attacks.

In July 2016, the U.S. Army included an entire section on the threat and how to respond to it on the battlefield in a new training manual called Techniques for Combined Arms for Air Defense. Category 1 and 2 drones were among “the greatest challenges for Army forces,” the handbook explained.

If they prove successful, the net-filled shells will likely only be one component of a suite of future weapons for the rapidly expanding mission of counter-small unmanned aerial systems (C-UAS). Since 2016, multiple pictures have appeared on social media of American troops actually fielding rifle-like jamming sets in Iraq and Syria. For a wider layer and more automative form of defense, the Air Force itself has reportedly bought limited numbers of an Israeli “Drone Guard” system and Liteye’s Anti-UAV Defense System (AUDS). On a higher-end of the spectrum, directed energy weapons and other counter-rocket, artillery and missile (C-RAM) like systems theoretically could make up the upper layer of area drone defense, but the Pentagon still has not fielded such a capability in a substantial and focused manner.

The SkyNet, and other systems in development, would definitely give Hyten’s security teams and other troops a safer option to take out tiny drones. However, it looks like the Pentagon’s overall strategy still have to catch up with the times.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com