On May 2, 2011, a group of special operators from the top secret Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) descended on an unassuming compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. In an ensuing fire-fight, members of SEAL Team Six shot and killed infamous Al Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden. Due to an accident during the operation, the elite troops had to leave behind evidence of previously unknown stealthy transport helicopter, likely related at least in part to the ubiquitous UH-60 Black Hawk.

The incident offered a rare window into the activities of the U.S. military’s most secret aviators and a look at their unique aircraft. Although the secretive 160th Special Operations Air Regiment, otherwise known as the “Nightstalkers,” may get all the attention, layers of clandestine units far more obscure exist. Some of them are silently blazing the path for special operations aviation’s future.

Though they often involve various military units and personnel from intelligence agencies, these sort of “black ops” are most commonly associated with the nebulous JSOC. When planning America’s most demanding military operations, which officials in Washington might never admit even occurred, these elements sometimes need very specialized aerial support.

So, with help primarily from the U.S. Army and Air Force, the Pentagon has steadily formed a permanent and secretive infrastructure to provide aircraft and helicopters for these missions. As of January 2017, this included at least four different units across the services and within JSOC itself: the joint Aviation Tactics Evaluation Group (AVTEG), the Army’s Flight Concepts Division and the Air Force’s 66th Air Operations Squadron and 427th Special Operations Squadron.

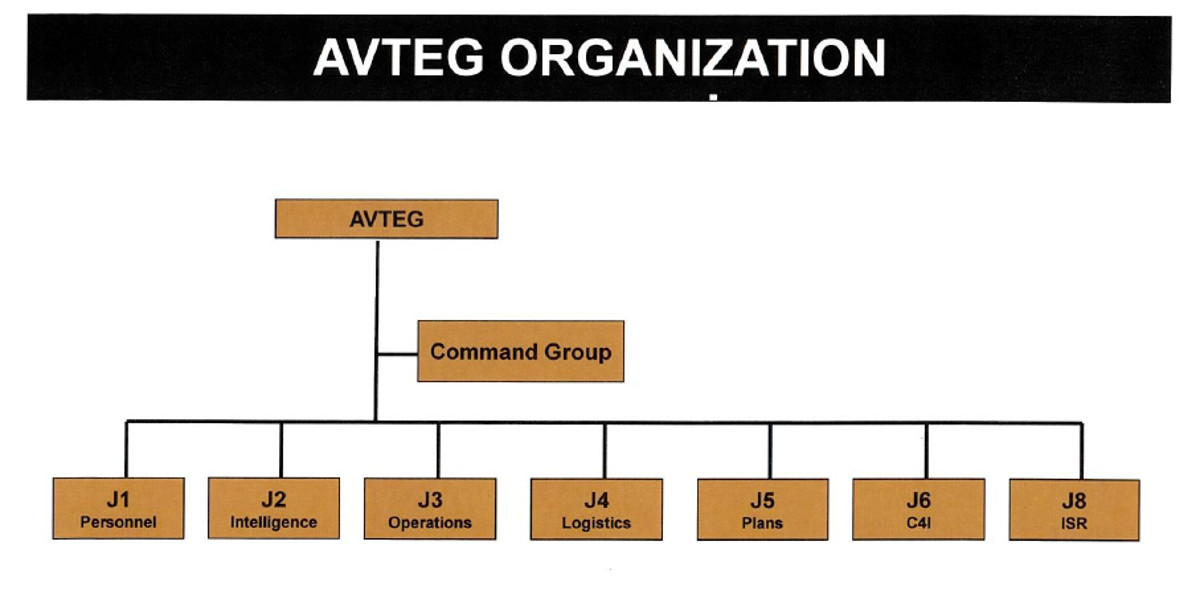

The bland-sounding AVTEG is situated at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the home of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command and JSOC. While little is known about this organization, thanks to the Freedom of Information Act, we can now present its official organization. The U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) provided the following chart in response to a request for information about the group’s organizational structure.

The breakdown is almost completely standard. A unit made up of individuals from across the services, AVTEG has a command group and seven “joint” offices, including typical administrative, operational and supporting elements.

The numbering scheme is standard across the Pentagon and the absence of a “J7” – usually set aside for a group in charge of creating joint operational plans, doctrine, training materials and exercises – is not necessarily notable. The sections specifically for Command, Control, Communications, Computers, and Intelligence (C4I) and Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) – distinct from the common operational and intelligence components – are more unusual.

With no description of the functions of these offices or details about their size and associated equipment, the chart provokes more questions than it answers. We have no idea whether or not it is even complete. Of course, none of that is surprising.

Details about the other units are similarly scant. The Air Force Historical Research Agency, which had official records on every unit in the service, has nothing in its file for the 427th after 1972. It does not list the 66th among active squadrons on its website, either.

It is possible that these are unofficial or cover designations rather than the formal nomenclature. However, the 427th resides at Pope Airfield in North Carolina and “provides U.S. Army [special operations forces] personnel opportunities to train on various types of aircraft for infiltration and exfiltration that they may encounter in lesser-developed training,” according to an official mission description that aviation researcher Andreas Parsch obtained through his own Freedom of Information Act request.

The only readily available public mention of the 66th is from an Air Force manual on forward-area refueling point (FARP) operations, which also name drops AVTEG. Both units are exempted from over-arching rules regarding pre-site surveys and “for short-notice exercises and contingencies, AVTEG and 66 AOS may authorize the use of temporary FARP sites” based on the service’s approved parameters, according to the handbook. Oh, and there’s also its awesome patch.

Researchers and journalists have found evidence that these Air Force squadrons fly a mix of traditional military type aircraft like the C-130 and less common types, including Cessna C-208 Grand Caravans, Pilatus PC-6s, and CASA 212s and C-295s, over the years. The service went so far as to assign the official designations U-27A and C-41A to the Caravan and 212, respectively.

There is even less information about the Flight Concepts Division or what aircraft it has in its inventory. But it would be reasonable to expect its fleet includes a diverse collection of American and foreign aircraft.

In his 2015 book Relentless Strike, Sean Naylor said this unit had quietly transformed into the E Squadron of the Army’s equally secret 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment D, more commonly known Delta Force. However, on July 8, 2015, Army Colonel Paul Olsen briefed Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Norfolk District’s work, in which he described work on the Flight Concepts Division’s hangar as something “you will soon see.” Again, its possible that one or more cover names is in use to refer to these units.

The obscure building itself sits secluded at Fort Eustis, Virginia behind multiple layers of fencing. The base’s fire chief isn’t even allowed in to check things out for emergency planning purposes. “Research activities are also conducted by the Flight Concepts Division that is highly secret and access for pre-planning purpose is non-existent,” an undated job posting explains. “Nature of their work is known to be hazardous.”

The exact relationship between these units, as well as AVTEG, remains unclear. There is, understandably, little official information available. A cursory Google search of .mil websites mainly turns up biographies of officers who list one of the elements among their previous positions, as well as vague job postings. Titles like “operations officer,” “troop commander,” and “fire support officer” are just standard military positions that offer no obvious clues as to the specific nature of the missions – no doubt by design.

Of course, the U.S. military has had these types of units for decades. However, by and large, they had historically been ad hoc formations that lasted only as long as specific conflicts. During World War II, in Europe, what was then the Army Air Forces used modified attack planes and medium and heavy bombers to drop intelligence agents behind enemy lines, insert Office of Strategic Services (OSS) teams – a precursor to both the Central Intelligence Agency and Army Special Forces – and resupply those efforts and friendly partisan troops.

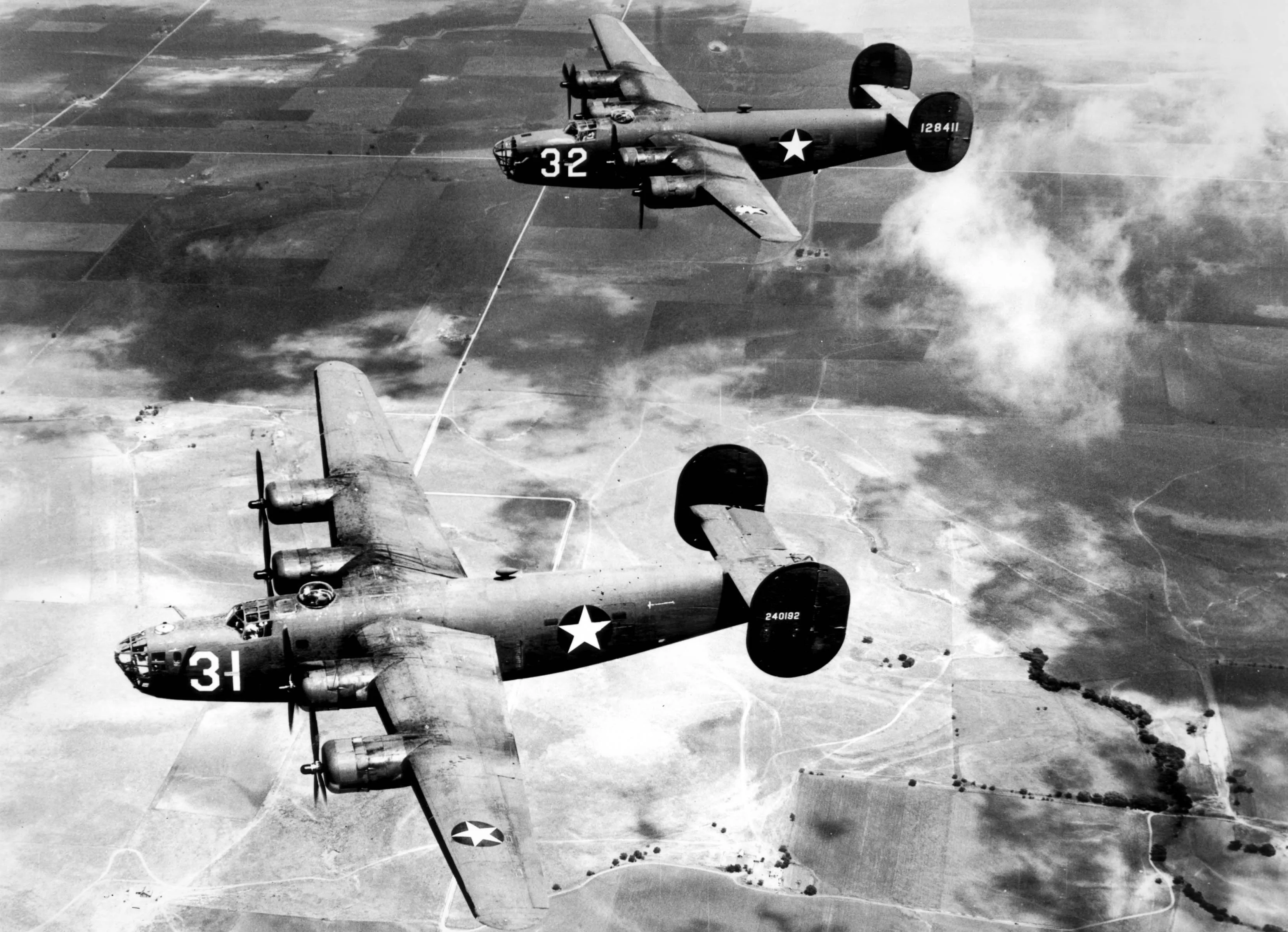

From the United Kingdom, the Eighth Air Force’s used the nicknamed “Carpetbagger” for its component of these operations. The 801st Bomb Group (Provisional) and then the 492nd Bomb Group flew the actual missions with a mix fleet of B-24 Liberators, C-47 Skytrains, A-26C Invaders and British Mosquitoes.

Another unit, which ultimately became the 885th Bomb Squadron (Heavy) (Special), conducted its own sorties first from sites in North Africa and then from bases in Italy. Similar “air commandos” supported operations in China, India and Southeast Asia, including providing dedicated air support for allied guerrilla units such as Merrill’s Marauders – the predecessors of the 75th Ranger Regiment – and the British Chindits.

When the war ended, the Pentagon shut them down, only to have to bring them back for the Korean War. This procedure continued for covert and clandestine missions around the world for much of the Cold War. The CIA created its own network of cover companies, including the famous Air America, for similar duties.

By the time America’s war in Southeast Asia was in full swing, things had not changed dramatically. To support an explosion of so-called “special activities” – covert and clandestine missions requiring the United States to be able to plausible deny involvement – in South Vietnam, Laos and then Cambodia, the Pentagon rushed to stand up new secretive aviation units.

In 1964, the top U.S. military headquarters in Vietnam created a single entity to handle these top-secret operations, blandly titled the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observation Group (MACV-SOG). Though regular and special operations units worked with MACV-SOG, the Airborne Studies Group (OPS-36) was responsible for dropping agents and propaganda leaflets into North Vietnam and Laos, as well as parachuting supplies to teamsalready on the ground.

The group’s First Flight Detachment at Nha Trang had six specially modified twin-engine C-123 Provider transports sporting a special dark-colored camouflage paint job and equipped with special navigational and communications gear. To help conceal American involvement in this operation, nicknamed Heavy Hook, American personnel trained Taiwanese and Vietnamese crews to fly the actual missions. Special brackets on the sides allowed personnel on the ground to swap out American and South Vietnamese Air Force insignia as necessary.

The C-123s were not particularly popular for the demanding missions. “The C-123 load capacity, operating range, and inability to fly in adverse weather greatly hampered airborne operations,” one 1964 review explained, according to a subsequent Air Force study of special missions. After initially resorting to shorter range helicopters, in 1965, the Pentagon approved plans to convert a number of four-engine C-130Es for specialized missions in Vietnam and elsewhere. These aircraft were the forerunners of the MC-130E Combat Talon and arrived at Nha Trang in 1966, where they joined the 15th Special Operations Squadron.

For a time, both the 15th and First Flight Detachment flew together. MACV-SOG used the codename “Heavy Chain” for missions involving C-130s. Air Force and Army UH-1, CH-3, and CH-53 helicopters, along with Air America and other private companies working for the CIA also provided support to MACV-SOG and other clandestine units in the region.

But “throughout the Vietnam conflict, [unconventional warfare] operations were tainted with the constant infusion of conventional military thinking,” the Air Force complained in its post-war review of special activities. “‘Dedicated air assets’ was a concept antithetical to the Air Force concept of the Single Manager – centralized control.”

So, despite these activities, when the Pentagon decided to launch Operation Ivory Coast in 1970, the daring raid on the Son Tay prison camp in North Vietnam, officials had to craft yet another temporary task force. This process repeated itself nearly a decade later for Operation Eagle Claw, the attempt to rescue American hostages in Iran who had been swept up in the country’s revolution.

That embarrassing debacle, which left eight Americans dead at a remote site named Desert One, provoked a significant amount of soul searching in Washington and increased support for developing a standing set of special operations units to respond to various crises. International terrorism, the War on Drugs, and continued Soviet-backed insurgencies had already contributed to the Army’s decision to create Delta Force in 1979 and the U.S. Navy forming SEAL Team Six the following year. This in turn led the U.S. military to ultimately create new secretive aviation elements to support those forces.

The most notable of these was a shared CIA and Army special operations element codenamed Seaspray, which reportedly had a mixed fleet of Hughes 500D helicopters and Cessna Grand Caravan and Beechcraft King Air fixed-wing aircraft. The Agency already had significant experience with flying specialized helicopters on top-secret missions, having crafted a pair of ultra-quiet, long-range, night-flying Hughes 500Ps as part of a project to tap phone lines in North Vietnam.

Based at Fort Eustis, the group flew covert and clandestine missions from the Middle East to Latin America, routinely working with Delta Force, SEAL Team Six and the Army’s Intelligence Support Activity. Authorities in Washington ultimately decided to clearly delineate the responsibilities of intelligence agencies from the military and gave the Army full control of the unit, who renamed it the Flight Concepts Division. The force has continued to operate since then, shielding its operations for at least for a time under the codename Quasar Talent, according to Michael Smith’s Killer Elite.

Though there is no official public record, it is likely the Air Force established the 427th and the 66th after Seaspray came under full military control as part of the Pentagon expanding these aviation capabilities. But there is little doubt these special operations aviators have been busy since the 1990s, though it may take decades for any formal information about their latest operations to come out into the light.

In December 2001, Russian authorities arrested a group of contractors working for the Army – reportedly for the Flight Concepts Division – and the CIA in the far-eastern city of Petropavlovsk. The group was trying to surreptitiously buy Mi-17 transport helicopters for operations in Afghanistan.

Nearly a decade later, there was the Bin Laden raid in Pakistan. Though members of the Army’s elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment reportedly flew the stealthy chopper, this was precisely the sort of product one could expect to see come out AVTEG or the Flight Concepts Division.

There’s also the matter of these shadowy Sikorsky S-92 helicopters operating in northern Syria surfaced on social media. For more than a year, these mysterious choppers had made appearances first at a major U.S. military base in Djibouti, then in Erbil in northern Iraq, and finally near the city of Kobani in Syria.

No one seems to know who owns these rotorcraft, which have been devoid of any national markings, but they could belong to various U.S. government outfits or another regional actor. Officially the Pentagon does not operate the S-92, but it is exactly the kind of “non-standard” or “off-the-books” aircraft AVTEG or another of the secret aviation elements might provide for discreet operations.

The fact that we don’t know for sure is the entire point of having these groups in the first place. We may just have to wait for another tidbit to turn up through FOIA – and hopefully not another accident during an actual operation – for the next set of new details to emerge.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com