In 2017, video and pictures of Islamic State fighters dropping modified and homemade grenades from quad-and hex-copter type drones highlighted the group’s ability to craft surprisingly advanced weapons. While novel, this particular combination is hardly the first time militants—and even established militaries—have turned to improvised aerial bombs in combat.

In September 1966, the U.S. Army’s top headquarters in South Vietnam told aviation units they were formally allowed to turn UH-1 helicopters into impromptu bombers. Yet for months already, Huey crews had been dropping modified mortar bombs on enemy positions.

The crews dubbed their creation the Mortar Aerial Delivery System (MADS), and some gave the choppers with the new gear installed the nickname “Mad Bombers.”

“Its simplicity of installation and operation provides a new dimension of fire support when difficult targets in mountainous areas are discovered,” one 1967 report from the 1st Cavalry Division declared.

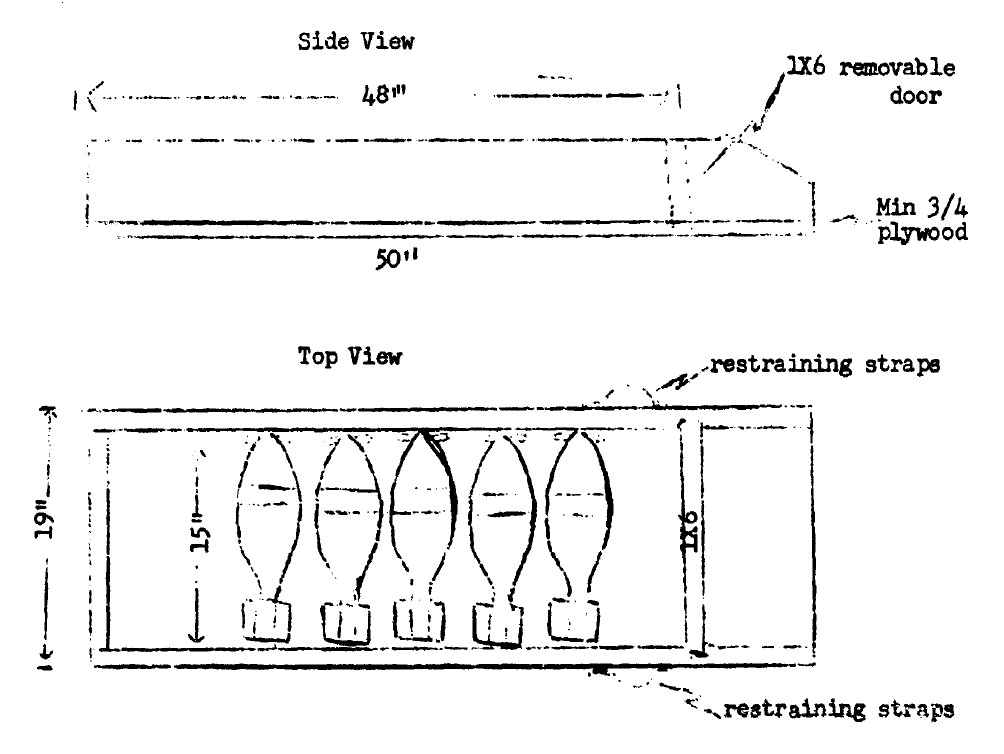

To say the system was simple would be generous. The original setup devised by troops from the 173rd Airborne Brigade and 145th Aviation Battalion was little more than an open-topped wooden chute mounted in the main cabin of either short-fuselage UH-1B/C gunships or the longer UH-1D/H transports. The entire assembly held 20 modified 81mm high explosive mortar rounds.

The procedure to turn them into small air-dropped bombs was relatively easy. Ground crews would first remove the projectile’s nose and base fuzes, as well as the propellant charges. Then they would install a World War II-era M158 bomb fuze, which would detonate the mortar-bomb’s explosive charge on impact. These fuzes had been available during World War II and Korea for use on a variety of larger weapons, including the 115-pound M70 and M70A1 mustard gas bombs.

Delivering the bombs was a similarly uncomplicated procedure. At one end of the chute, technicians had cut a slot and slipped in a removable plywood board. At the right moment, a member of the crew would manually pull this stopper out and the mortar bombs would just roll out.

How would you know how when that moment had arrived? The pilot would point the chopper at the target while flying at approximately 2,500 feet high. Then he would wait until the target lined up with a part of his foot pedal through the small windows underneath the Huey’s nose.

“Sensing the mortar rounds as they detonate, adjustments for target sight picture and wind conditions can be made and greater accuracy will result,” a standard operating procedure the 145th drafted in April 1966 explained. In short, there was a lot of personal skill involved in putting the small bombs in the right place.

The weapon was perfect for scattering potential ambushers from landing zones, attacking enemy forces on the ground during aerial assaults, or simply blasting targets of opportunity, including reinforced bunkers the Viet Cong built in remote areas, according to the MADS procedures.

But wary of complaints from the U.S. Air Force about stealing its roles and missions, the Army aviators were quick to point out that “the ‘MAD’ system in no way duplicates or parallels the prestrike, or landing zone preparation and close air support mission of the USAF Tactical Air.”

After the Pentagon created the independent Air Force in 1947, it repeatedly sparred with the Army over which service would get to fly which missions and how. During Vietnam War, with the Air Force continued to complain about Army fixed-and rotary-wing encroaching on its turf.

So to read the reports, the “Mad Bomber” was just another piece of artillery. The gear simply allowed ground commanders to put more mortar rounds on target faster and more accurately.

Still, “a variety of targets may be engaged with accuracy and the tactical employment of this weapons system is unlimited,” the 145th’s guide declared. “Excellent results have been obtained when this weapons system is employed against targets located in dense jungle areas where secondary forest canopies are prevalent.”

And barred by agreement with the Air Force from flying fixed-wing attack aircraft, the Army was very interested in the potential of the new armament, no matter how crude. After learning about the weapon, and with the approval of the Army’s top officers in South Vietnam, the 1st and 25th Infantry Division and 1st Cavalry began to test out the MADS.

The units’ experiences over the course in nearly three years of operations differed wildly. The 1st Cavalry Division, operating from bases in South Vietnam’s central highlands, found the setup effective in the rugged terrain.

In July 1967, the division went so far as to produce a study of MADS operations, which included “means of overcoming the factors which decrease the accuracy of the system, e.g., airspeed, altitude, moving targets, etc,” according to another report. The 2nd Battalion, 20th Artillery Regiment, an aerial rocket artillery unit equipped with UH-1 gunships toting 2.75-inch rockets, had developed their own version of the system, though it’s unclear what improvements the troops made to the initial design.

The next month, the Army added sections on dropping mortar and cluster bombs from helicopters to official field manuals. The official doctrine specifically described rotary-wing bombers—not mentioning of the Huey specifically, as CH-47 units were flying similar missions—as a substitute for mortars in challenging environments.

“The responsiveness of this support is reduced when the mortar and its ammunition must be transported over difficult terrain by foot-mobile units,” the amended manual explained. “The use of armed helicopters for delivery of droppable munitions, to include modified mortar projectiles, and cluster bomb units (CBU) can be integrated into the ground unit’s plan action.”

But elsewhere, Army Major Gen. Fillmore Mearns, head of the 25th Infantry Division situated northwest of the country’s capital Saigon near the Cambodian border, decided the system wasn’t really all that useful. More than a year later, however, his successor Army Major Gen. Ellis Williamson apparently came to a different conclusion.

“This system has been found to be useful…to deliver ordinance that otherwise cannot be effectively placed due to heavy jungle canopy,” the division’s staff explained in January 1969 review of recent operations. “MADS is, in some situations…an effective substitute for infantry high angle of fire weapons that cannot be employed due to triple overhead canopy jungle.”

However, “the system is not recommended for use by other aviation units as in other types of terrain, the stand off

capability of armed helicopters employing rockets is considered an adequate fire support means,” the report added.

Shortly afterwards, the 1st Infantry Division, situated nearby, also arrived at the conclusion that the mortar bombs were in no way a substitute for artillery. Instead, the division’s 1st Aviation Battalion used the chutes to drop sensors to try and catch insurgents moving around in the jungle below. The aviators also dropped white phosphorus rounds to mark targets and even built a version that could handle larger 4.2-inch mortar rounds.

The improvised flare launcher that did make it into the 1971 report.

, US Army via Ray WilhiteNeedless to say, units’ opinions of the “Mad Bomber” were decidedly mixed. A 1971 Army compendium of field expedient helicopter modifications in South Vietnam doesn’t mention the system at all, though a locally-made flare dispenser did get a mention. Despite the reported combat use, there are no readily available pictures of the MADS in action.

After the fighting in Southeast Asia ended, the Army made no effort to refine the MADS concept. Today, the weapon is just one footnote in the history of aviation operations during the Vietnam War.

However, the basic idea of a small, low cost aerial weapon never went away. In 2012, General Dynamics and the Army announced successful work on a kit to turn regular 81 mm mortar rounds into small guided bombs for small drones. It’s possible the U.S. military dropped one of these Roll Control Guided Mortars (RCGM), or a similar, improved weapon, on Al Qaeda deputy leader Abu Khayr al Masri in Syria in February 2017. Of course, the RCGM’s GPS-guidance is decided more advanced than rolling bombs out the door of Huey.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com