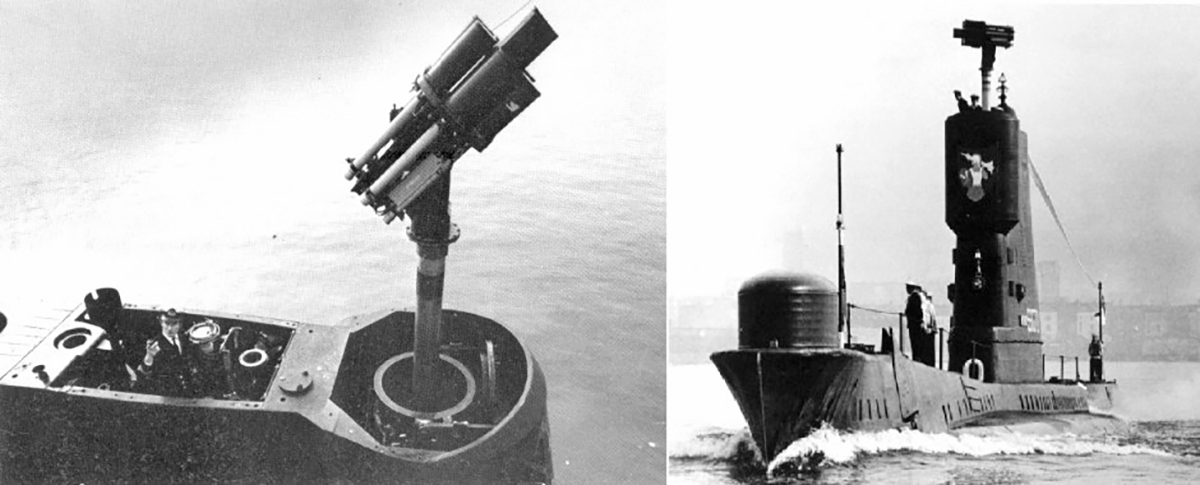

The concept dates back to the dawn of aerial anti-submarine warfare, when anti-aircraft guns were mounted on the decks of submarines to defend themselves against aerial attack while surfaced. During the Cold War, man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) were tested by the Soviets on submarine periscopes. Nothing much came of it as targeting was a troublesome affair. NATO countries also played around with the idea. The UK went maybe the farthest, with a submarine-launched version of the Blowpipe missile.

The concept featured four remotely controlled missiles clustered around a TV camera, mounted atop a telescoping mast on the sub’s sail. The seaborn Blowfish never saw widespread operational use, but there are rumors that the Israelis did purchase the system. Now, decades later, submarine-launched air missiles (SLAMs) are back on the table, but are they necessary—or even tactically viable?

Not a one-size-fits-all capability

Emerging SLAM capabilities come in a few flavors of complexity, and some still remain more theoretical than operational. The simplest of these new systems is similar to the UK’s Blowpipe concept, as it encloses an existing MANPADS air-to-air missile design in a pod attached to a turret mounted atop a submarine’s telescoping mast. The idea is that, if the submarine was cornered by an aerial anti-submarine asset, it could pop up to a very shallow depth, extend the anti-aircraft missile system, lock up the target and kill it. Hopefully doing so would give the submarine time to slip away, assuming no other anti-submarine assets were nearby.

The French A3SM submarine-launched MICA missile system is based on this same concept, and the Russians supposedly have developed a similar system for use on their Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines. It remains unclear if this capability has been deployed, either domestically or to one of the Kilo class’s many export customers.

A more advanced SLAM concept offers better survivability and maneuvering flexibility for the launching submarine, but it’s far more complex than the basic mast-mounted A3SM. This concept utilizes a torpedo-like underwater vehicle fired from the submarine that makes its way to the surface. Once there, it releases its missile—or missiles. Alternatively, no canister or vehicle may be needed at all, and the missile may be able to make its way to the surface and fly out without any assistance at all.

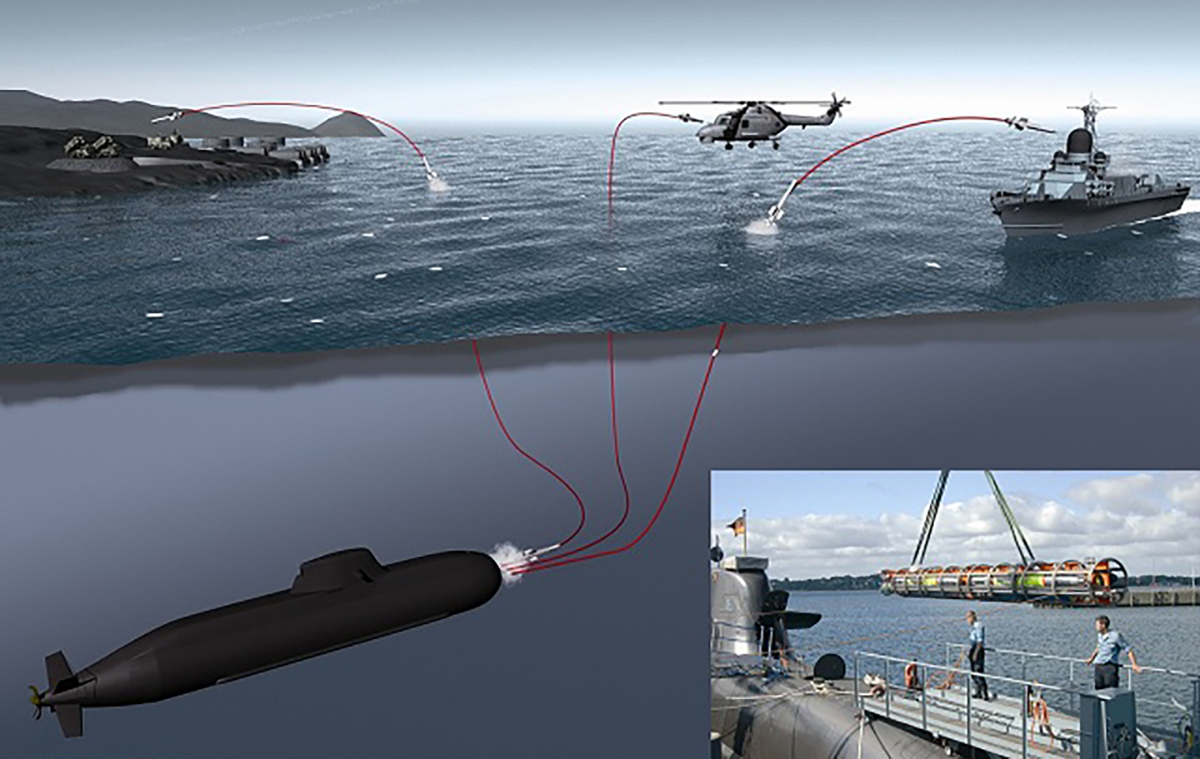

One such system test fired by both German and Norwegian diesel-electric submarines is the Interactive Defense and Attack System (IDAS) built primarily by Diehl Defense.

Initially designed for Germany’s popular Type 212 family of submarines, the missile itself is based loosely on the IRIS-T short-to-intermediate range air-to-air missile, but it travels at a subsonic speed and trails a fiber-optic cable. Like the French MICA, the IDAS primarily uses infrared homing to engage its target; but other seekers can be fitted, and the system is envisioned to even be used against small surface and shore targets in the future. Because a wired link between the submarine and the missile is kept at all times, target ID and even damage assessment can be made by the submarine crew during the engagement.

Here is Defense Update’s description of IDAS:

“Four missiles will be stored in a magazine that fits into a standard 21″ torpedo tube. The missiles are ejected from the magazine into the water, extract their wings and separate quietly from the submarine, where they ignite the rocket and transition to airborne flight, propelled by the weapon’s rocket motor.

One of the development challenges was the propulsion system. The same rocket was required to provide thrust for both underwater and airborne flight. The rocket was designed to sustain the missiles at optimal velocity in submerged flight, and accelerate to subsonic flight while airborne, reaching effective range of 20 km. Another concern was sustaining the optical-fiber through the transit below and above water. Diehl’s engineers were concerned how the fiberoptic bobbins will behave in the different environments (below and above water) the test provided clear evidence this will not be an issue.

Diehl initially considered using the IRST seeker for IDAS, however, this high performance and all aspect seeker may not be the only option, and other seekers might be considered to pick up the target, provided with passive cuing from by the submarine sonar. The submarine can acquire ASW helicopter when submerged, by localizing the ripple effect created by the rotor downwash. According to Diehl, the accuracy of such cuing system is adequate to provide bearing and range, bringing the missile seeker to autonomously acquire the target with high level of confidence. The fiber optical link would then be used by the crew to verify the target, confirm the intercept and perform battle damage assessment.”

The French also have a system under development that uses the Mistral short-range MANPADS missile twin-packed into a torpedo-like vehicle that brings the missiles to the surface before launching on their own power into the air.

The US Navy also played with a similar concept that has blurred into the developmental shadows in recent years. During the late 2000s, the US Navy, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman worked to migrate the highly flexible AIM-9X short-range air-to-air missile to the undersea world under the Littoral Warfare Weapon program. The AIM-9X would be vertically launched in a canister from a submarine, then the missile would climb into the sky when the canister broke the surface, locking onto its target after launch.

Tests during the mid 2000s had the AIM-9X fired from a vertical launcher as a proof of concept demonstration. A few years later, an AIM-9X was launched from an actual submarine as part of a series of integration tests. Since then the program seems to have disappeared from public view, but it’s likely development has continued on in the classified world—especially considering that submarine-launched unmanned aircraft have been an operational reality within America’s nuclear submarine fleet for some time.

Other more elaborate concepts exist where short-range air-to-air missiles are mounted inside existing cruise missile designs. The submarine launches the missile which then performers a pre-selected low-level patrol pattern in the area of the submarine, giving it a form of top cover. If its radar or electronic sensor suite picks up an aerial contact, it pursues it and launches missiles at it.

Although this type of concept is highly intriguing, it is also very expensive, complex and calls into question the ethical issues of unmanned weapon system autonomy that the DoD is struggling with today. Not just that but the presence of the missile is a great sign that an enemy submarine is nearby. There are no clear indications that this type of submarine-launched counter-air capability is actively being developed at this time, but that could change considering how the marketplace is evolving.

Pros and cons

There’s clearly development and investment within the global defense industry for SLAM systems, so there has to be a strengthening demand for them right? Well, don’t consider the case for them to be overwhelming. Think of these systems as a last line of defense for submarines that have been located, and are facing imminent death from an aerial asset above. Using them as an offensive weapon is highly unlikely and tactically bankrupt in almost all circumstances.

This is especially true for systems like the A3SM, which require the sub to come very near the surface for a shot on a helicopter operating low, slow, and relatively close by. This leaves the submarine vulnerable, and likely results in a showdown between the ASW aircraft and submarine itself—one in which the first to fire might be pulling the trigger on a major conflict as well.

Then again, a submarine downing one ASW helicopter at near-point-blank range doesn’t necessarily mean the nationality of the sub that fired the deadly shot would have been known prior. Popular submarines designs can be used by multiple countries in a single region, some of them being potential foes of one-another. Pair this with the murky world that these weapons currently reside in today and you begin to deduct that plausible deniability of such an act could be a real possibility.

Most modern ASW helicopters and low-flying maritime patrol aircraft have advanced and highly automated infrared countermeasures suites. While a submarine may be able to get a SLAM launch off, it doesn’t mean they’ll kill their target. Worse for the sub, initiating such an attack will also clearly give away their presence and their intent. If they don’t eliminate nearby aerial threats in the process of their attack, they’ve pretty much guaranteed their own destruction.

There’s also the question of targeting: On lower-end systems, a small, high-frequency radar extended on one of the boat’s masts can cue the turret for targeting, or an infrared camera system could be used, albeit less effectively. Combining a radar and infrared camera would offer both target discrimination and quick detection and engagement capabilities. This is a lot of gear to install on the limited real-estate of a submarine’s conning tower/sail.

For more advanced SLAM concepts where a canister or the missile itself is launched to surface, getting the missiles in the right area and hunting in the right direction quickly is key. The boat’s passive sonar could be used for initial, albeit lower fidelity, targeting. Then the missile’s gimbaled, high-off bore-sight seeker head can quickly scan for its target in a section of predesignated sky as it lifts off from the surface. All this sounds good on paper—and probably looks cool in a powerpoint presentation—but getting it to work reliably, quickly, and in a broad range of environmental conditions may not be an easy proposition. In the end the system has to be reliable, as a missed shot is likely worse than no shot at all.

There is a deterrence factor that must also be credited to a weapon system like this. For anti-submarine warfare helicopter and maritime patrol aircraft crews, knowing that your prey can bite back could change the game substantially. Then again, it’s a double-edged sword. If the submarine fires at an ASW aircraft, air crews will know where that submarine is and can immediately prosecute their own attack—and rules of engagement would probably dictate doing so.

ASW tactics can also be modified to deal with the threat of SLAM equipped submarines. Hunting in larger groups of diversified aerial assets, or at least in pairs, would give sub-killers and advantage, and are already a well honed and widely used ASW strategy. Additionally, modern anti-submarine weaponry is featuring more standoff capability than ever before, keeping potential targets outside a submarine’s SLAM reach.

Knowing an enemy’s submarines were armed with anti-aircraft capabilities may actually work against that submarine, as it could make the sub hunting aircraft’s tactics, and their assigned rules of engagement, far more aggressive than they would be otherwise.

There is also the question of if naval commanders would want this type of weapon on their submarines at all, as it gives a submarine commander a possible out once detected. The whole idea of submarine warfare centers around not being detected in the first place—such a weapon system may have a hard time fitting into that proven concept of operations.

Who needs it most, if anyone?

So are submarine-launched air missiles really a capability we’ll find widespread on submarines in the future? Maybe: But there will be a clear delineation in the motives of the countries that deploy them.

These systems might prove most valuable on diesel-electric submarines, especially those that are not air-independent propulsion (AIP) equipped, and have to surface far more often to recharge their batteries. With the window for undersea operations narrowed, a SLAM at least gives air-breathing subs a shot at defending themselves from an imminent attack.

These boats spend much of their operational careers close to shore in littoral combat environments where hiding places are prevalent, but once detected, escape options may be limited. But even then, SLAMs would be a weapon of last resort—used under extreme circumstances due to its massive implications.

Another hindrance is that diesel electric subs have less space for weaponry and sensor masts than their larger and more complex nuclear counterparts. Taking up valuable real estate with a questionable last line of defense weapon may prove unpalatable. IDAS, with its potential land and surface attack capability, would at least exchange multi-role flexibility for the space it takes up and the cost of integration and training.

Considering China’s large fleet of diesel-electric submarines, shallow operating areas in the South China Sea, and the prevalence of American, Japanese and other navies in the region operating high-quality anti-submarine warfare capabilities, a Chinese SLAM may become a reality in the near future. In fact, the PLAN has worked on various submarine-based anti-aircraft weapons concepts in the past.

Israel’s Dolphin class diesel-electric boats are used as second-strike nuclear deterrents when outfitted with nuclear-tipped Popeye Turbo cruise missiles. During these patrols, it’s the boat’s job to go hide for long periods of time. Leveraging AIP technology, they can do this for days or even weeks at a time. Considering they could be called upon to enact nuclear revenge at any moment, adding a counter-air missile to their quiver may be just a logical step in ensuring that their mission will succeed, no matter the circumstances.

Nuclear submarine-equipped countries like the UK, France and especially the US may end up fielding SLAMs—or they may already have—because it’s just another integrated capability to have at the submarine commander’s fingertips. These boats cost billions of dollars each. Spending a comparatively small amount on additional capabilities, even capabilities with very narrow use, is not out of the question, especially since we already spend billions on other capabilities that have a low probability of use. Also keeping in mind where these big stealth vessels go, having a new tool to get away alive from a prowling ASW helicopter may be a better solution for a boat filled with a nation’s most guarded military technology secrets than getting sunk deep in enemy territory. Finally, there’s more room on these boats to deploy new capabilities compared to their relatively tiny diesel-electric cousins. Giving up one vertical launch tube—if even that—for a submarine derringer pistol of sorts is not such a huge sacrifice.

So yes, there may be a place for SLAMs after all—and the marketplace for such a capability will likely grow in the coming decade.

Is it a necessary capability? That depends on how you look at it, and how navies plan to employ the weapon. But generally, no. The systems conflict with the traditional tactics of subsurface warfare. If the cost isn’t horrendous, and the integration challenges aren’t severe, the question shifts to one of why not? If the cost is significant and the integration issues are intense, even wealthy navies would be better off spending their money keeping their boats from being detected in the first place.

No matter what, robust training programs featuring various engagement scenarios will have to be funded and fielded in order to leverage a SLAM system reliably once a boat is equipped with it. If a Navy is unwilling to come to terms with this additional cost—one that will remain persistent as long as the system is deployed—then they should save their money.

In the end, should submarine-launched air missiles become widely proliferated, they will be countered with increasingly effective countermeasures suites on ASW aircraft, as well as changes in standard operating procedures and applied tactics by ASW forces. Like all things subsurface warfare, the game of measure and countermeasure will take off running, with no end in sight.

Contact the author Tyler@thedrive.com