Ballistic missile defense (BMD) is always a tough topic to address technically because it’s far from monolithic in nature. What makes up America’s still relatively rickety concept knows collectively as BMD are a wide ranging cocktail of capabilities, some of which are more intertwined than others. Anti-ballistic missile capabilities can largely be adapted into anti-satellite capabilities, which are at the heart of growing fears that space is becoming the high-stakes battlefield of tomorrow.

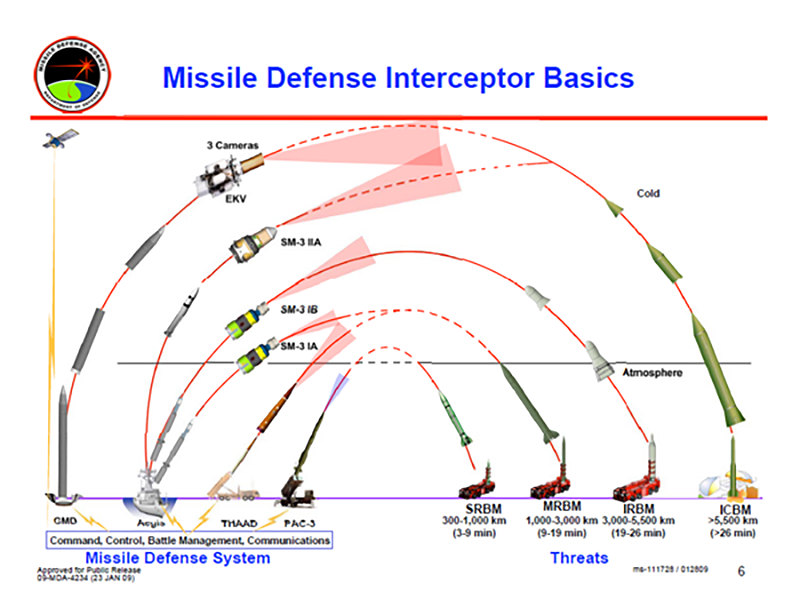

Layers of defenses, each focusing primarily on a flight profile of a certain category of ballistic missile, with some overlap in between, utilize an array of interceptors and sensors to get the job done. The MIM-104 Patriot missile battery can be used to counter short-range ballistic missiles over a localized area. THAAD is aimed at taking out medium to intermediate range ballistic missiles within a specific theatre of conflict. AEGIS at sea and ashore can swat medium to longer-range ballistic missiles out of the sky within an entire region. Finally, there’s America’s hulking ground-based long-range interceptors focused on taking out ICBMs before their warheads descend onto the US.

All these systems are supported by a massive array of remote sensors and communications nodes, ranging from a constellation of orbital infrared surveillance systems, to a shy fleet of massive radar equipped tracking ships. This short primer video made by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) goes specifically over longer-range midcourse ballistic missile defense and the challenges that go along with it:

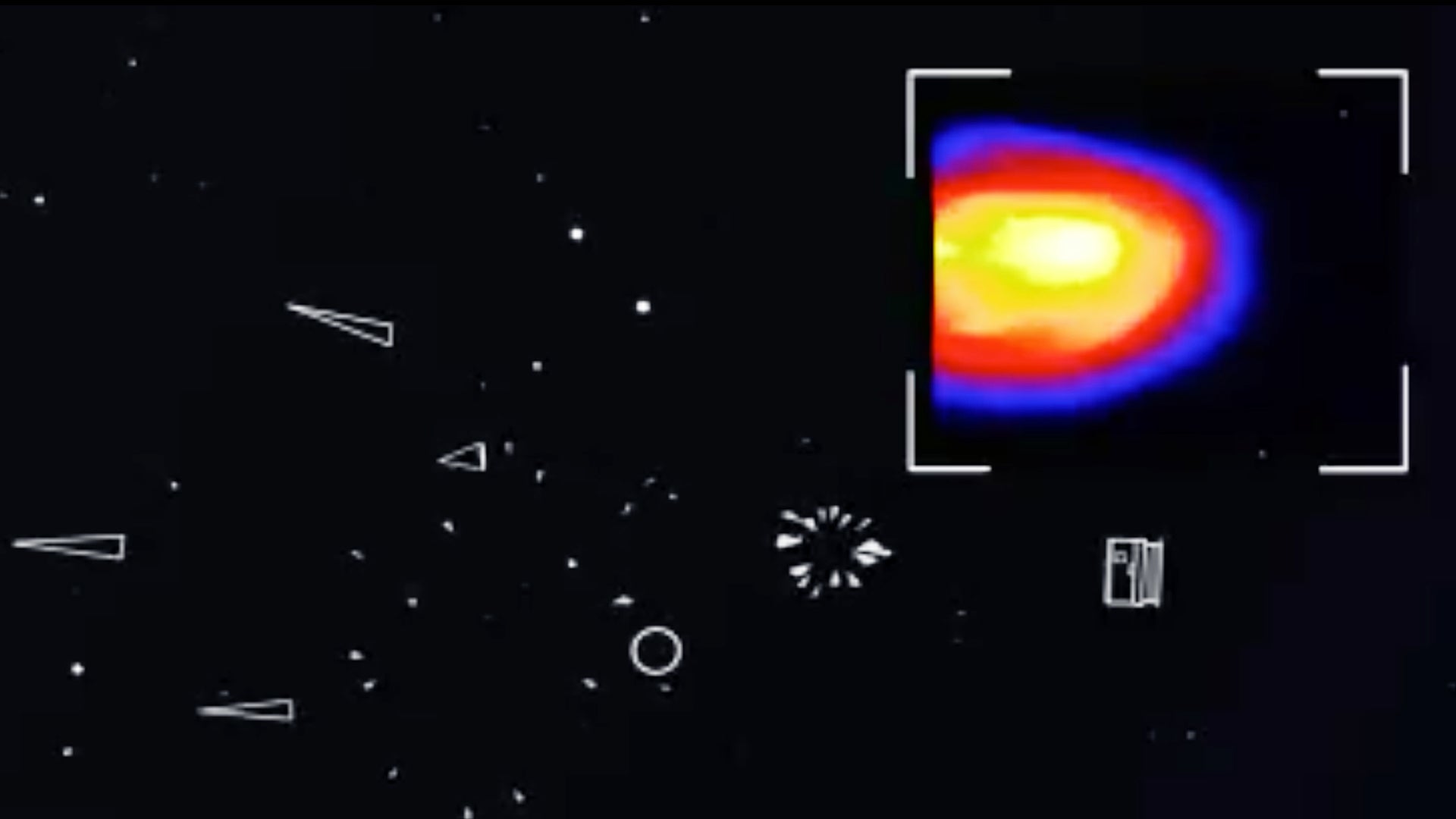

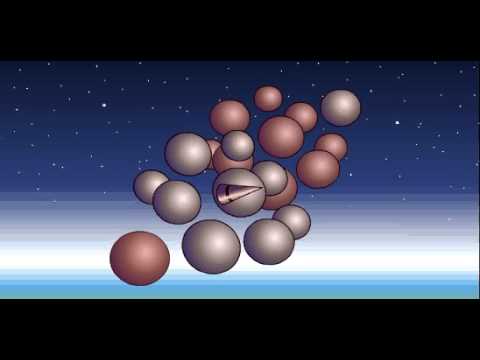

The video makes the point that the more disparate sensor data fuse together during an intercept, the better chances that that intercept will be successful. Some shadowy areas of this capability include satellites that can track “cold bodies” traveling atop earth’s atmosphere at acute viewing angles. By taking all these data sources and fusing their information together, high-speed computing and AI can predict which objects are within the “threat cloud” are an actual threat while excluding debris and multiple types of countermeasures.

Once identified, an interceptor vehicle, or vehicles, can execute a terminal attack plan on the object and even better identify it using their own sensitive onboard infrared sensors. This is similar to how long-range air-to-air missiles can be guided by data-link using “third party” telemetry towards their targets over great distances, and then use their sensitive imaging infrared or radar seekers to make an automated high-probability of kill terminal attack on the most vulnerable part of the target.

It all comes down to the need for better target discrimination, thus enhancing the probability of kill for each interceptor fired. Currently, Russia’s most advanced long-range ballistic missiles have robust capabilities to confuse and even surprise American anti-ballistic missile defenses. The truth is, America’s BMD capabilities are nowhere near advanced or numerous enough to have any chance of countering an ICBM barrage from a peer-state competitor, and especially one from Russia. So for now, even though it remains fairly immature after many billions spent, the system provides a decent defense against short to medium-range ballistic missiles in regions and theaters of combat, and a some level of plausible defense against small volume ICBM attacks on the US.

Trump will likely push to enhance America’s BMD capabilities. But with so many other pressing needs, not to mention a whole stack of other expensive promises he made during the campaign, we will have to wait and see if BMD becomes a larger investment sink for the DoD.

Contact the author Tyler@thedrive.com