On January 4th, 2017, one of a B-52H’s eight Pratt & Whitney TF33 turbofan engines detached from the jet mid-air, plunging thousands of feet into a sparsely populated area about 25 miles northeast of Minot AFB, North Dakota. The B-52 was not loaded with live ordnance at the time, and its five crew were able to make it back to Minot safely—but the idea that one of the aircraft’s engines literally fell off is bizarre and unnerving to say the least.

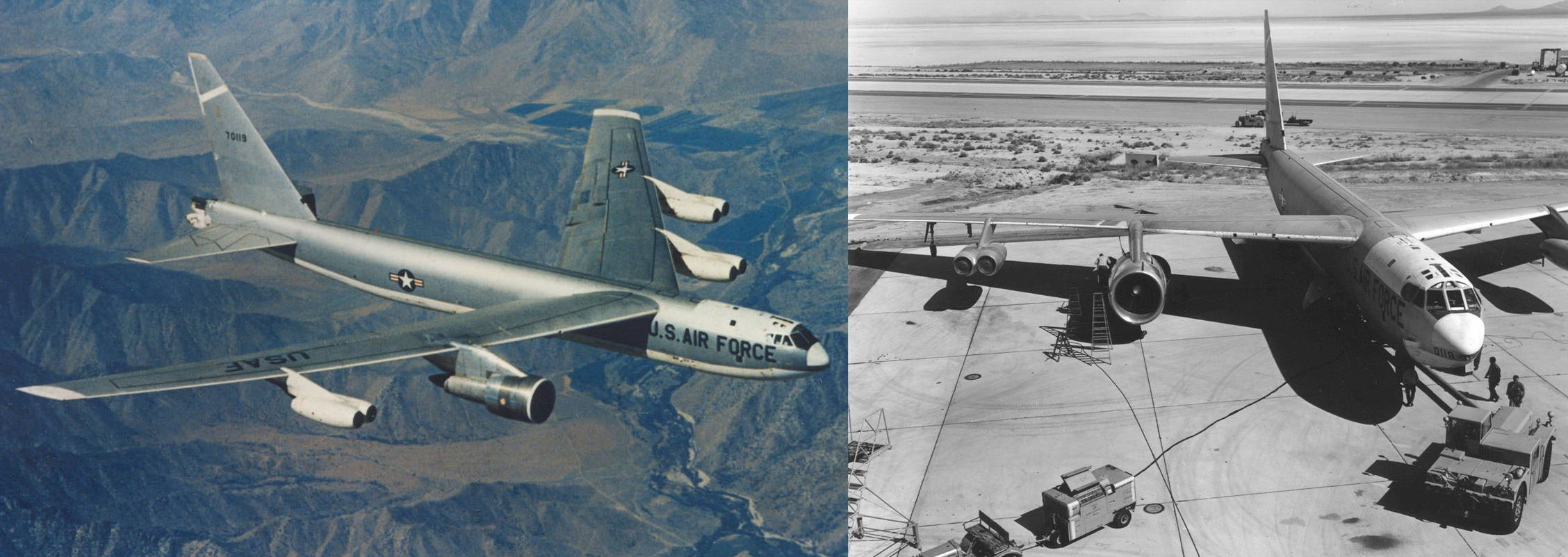

Stranger still is that the jet’s engines are paired, two go in each nacelle pod, which is attached to one of four pylons under the aircraft’s wing. It’s being reported that a single engine fell away from the aircraft—not two that make up a pod—which makes the incident more puzzling as it would indicate the engine detached from the shared mounting pylon, taking its whole nacelle housing with it. Fortunately for the B-52 crew, having an aircraft’s power spread across eight engines means that that losing one, even far towards the wing tip, does not cause massive thrust imbalances.

Regardless of whether this incident ends up being a result of human error or a faulty component, it will likely fuel calls for the B-52’s re-engine program to finally be executed. Attempts to mount new powerplants on the BUFF have been frequent over the last four decades, often with different powerplant choices and different funding schemes motivating them. We have discussed all this in great detail in the past—and the stark reality is that upgrading the B-52’s engines is long overdue—especially considering the technological upgrades and game-changing weaponry the B-52 is receiving. Not to mention the potential for what the type could morph into in the future, or that it’s slated to serve till at least 2040.

Barring the very low chance of an early B-52 retirement following a massive investment into the new B-21 Raider program, any new engine initiative for the B-52 would likely come under a complex private-public sector cooperative, where the new engines are “paid for” by theoretical fuel savings over time. What the USAF will get in the process is a much more capable bomber—one that features higher reliability, less maintenance per flight hour, dramatically longer range and loitering time, higher altitude operations, and more lifting ability while utilizing shorter runways.That improved short-field performance could come in very handy for forward deployed operations to the Pacific, and further the use of the B-52H’s new “smart” internal weapons rack. Other benefits of new engines include greater power generation abilities—useful in supporting potential future roles toting directed energy weapons or acting as a standoff jamming and electronic warfare platform.

The last time the USAF researched what it would need out of an engine program was 2014, when it concluded that new powerplants would need to save between 10-25% in fuel consumption, and would have to go 15-25 years before the first deep overhauls of the engines are required. The question of which engine would best fit this requirement remains, as well as whether four large engines or eight smaller ones (even six, under some concepts) would be best.

One area of concern is if new pylons would be needed to accommodate powerplants mounted in new locations under the BUFF’s wings. Such a requirement could result in a costly re-engineering of the B-52’s wings. With four larger engines, such as GE’s CF6 (called the F138 on the C-5M) or engines similar in size to the Pratt & Whitney PW2000 (the F117, in use aboard the C-17A) wing height and rudder authority for engine-out operations remain a question. As as result, costly flight control and avionics upgrades might be needed to accommodate their use, beyond the need for potential structural upgrades to the B-52’s wings.

With this in mind, probably the easiest option is eight compact high-bypass turbofans fitted to the aircraft’s existing pylons in re-contoured dual-nacelle pods. The Rolls Royce BR725 powering the Gulfstream 650 is one contender, as is GE’s Passport 20 found on the Global Express 7000 and 8000. If the Air Force decides to push forward with an official RFP for an engine swap on the B-52, other entrants will surely emerge.

Although there are only 76 B-52Hs in service, eight engines for each jet equals a whopping 608 in total. With spares, a B-52 re-engine initiative could equal an order for well over 650 engines. During a time when fewer types of military aircraft are being put into production, such an order—even if less lucrative up-front than a flat-out purchase—could represent a large injection of revenue to the winning manufacturer.

Meanwhile, Pratt and Whitney, the original manufacturer of the B-52’s engines, has been pushing for the USAF to adopt a package of improvements for existing TF33s flying on the B-52 Stratofortress, E-3 Sentry and E-8C JSTARS fleets. Squeezing more reliability out of the 55 year old TF33/JT3D design may be possible, but large improvements in fuel economy and drastic gains in performance are not.

A lot of this will come down to what type of priority the Trump administration will place on the B-52 fleet going forward. He has been known to slam the jet’s age in the past, although that is common among politicians uneducated in the aircraft’s unique abilities.

By leveraging a “save to pay” scheme, where both industry and the Pentagon assume some risk, such a program may fit well into the President elect’s new vision for a reformed Pentagon procurement process. Then again, Trump himself seems to have no problem operating aging aircraft that guzzle a lot of gas and cost huge sums of money to keep flying. Fuel costs have been down for years, from their high in the late 2000s, which also hurts the business case for recapitalizing the B-52’s power plants. But as we discussed, it’s not all about fuel savings, but also large increases in capability and drastic enhancements in reliability and maintainability. There is no crystal ball that can predict future fuel pricing with 100% accuracy, and you simply don’t strap new engines on an aircraft like this—it takes time. As such, the Air Force would be better off biting the bullet, beginning the process has to be better than agreeing to rely on an engine design that will be approaching a century of service when the B-52H is finally put out to pasture.

Contact the author Tyler@thedrive.com