CBS’s iconic news magazine seems to be launching a major investigation into America’s changing strategic place in the world. A few weeks ago, 60 Minutes offered a fascinating look inside Strategic Command and some of its most shy assets. Two weeks ago, the second part of that series explored America’s nuclear posture and how Russia may not see the use of nuclear weapons in the same light as the US. Then this week, Leslie Stall ventured up to Arctic to report on ICEX 2016, where she talked the changing geopolitical winds blowing in the far north, the looming specter of climate change, and took a ride on nuclear fast attack sub.

The second part of David Martin’s New Cold War expose (see the first part here) highlights something that I have long posited—the reality that limited peer state warfare, and even the selective use of tactical nuclear weapons during such a conflict, is not unthinkable. In fact, “escalating to deescalate” is a very real tactic, one that seems to fit (albeit in an extreme manner) with Russia’s strategic playbook lately.

Even a tactical nuclear weapon used in an unpopulated area, or on an isolated military target, draws a high stakes line in the sand. This is a point of departure towards either deescalation or armageddon. It tosses the metaphorical ball into the other guy’s court, at which point he will have to decide whether the risk of a major nuclear exchange is worth trying to retake the limited territory the enemy has already seized.

Watch this second part of David Martin’s New Cold War expose here.

In the segment, Martin sat down with Philip Breedlove, former Commander, U.S. European Command, as well as the 17th Supreme Allied Commander of NATO until last May. The discussion was characteristically frank:

Breedlove: They see nuclear weapons as a normal extension of a conventional conflict.

Martin: So to them nuclear war is not unthinkable?

Breedlove: I think to them the use of nuclear weapons is not unthinkable.

Later, Martin talks with Admiral Steve Parode, the director of intelligence for US Strategic Command:

Parode: I think that they feel that fundamentally the West is sociologically weaker, and if they were to use a nuclear weapon in the course of a conflict between, say, NATO and Russia, they might be able to shock the Western powers into de-escalating, freezing the conflict, into calling a cease-fire.

Martin: So they have a belief that they’re just tougher than us?

Parode: Oh, that’s definitely true.

Martin: And if they have to use nuclear weapons, we can’t, we can’t take it?

Parode: I think that some people might think that.

Martin: So, how would they shock us into surrender?

Parode: They could strike a European target with a nuclear weapon, maybe an airfield they thought was vital to conflict between NATO and Russia.

The reality is that massive retaliation is not America’s nuclear policy. Flexible (or scaled) response is really the policy that is in place today and has been for decades. Under such a policy the President can chose to respond to the use of nuclear weapons in a tit-for-tat manner, including the use of non-nuclear means for retaliation. Or the President has the ability to execute an overwhelming response, where one nuclear weapon used by the enemy could see many more used against them in a rapidly escalating conflict model. It is all up to the Commander In Chief, and they would likely have very little time to make such a decision.

Underlying this strategy is America’s second-strike deterrent and the idea of mutually assured destruction, which could be the end game in any nuclear exchange between Russia and the US. So it is not as if say Russia were to use a tactical nuclear weapon to plug a gap on the battlefield, and in doing so attempt to freeze a limited conflict by calling America’s bluff when it comes to nuclear escalation, that the US would have to retaliate with all or even a sizable amount of its nuclear stockpile. Although such a strong response remains an option, it has limited utility unless it is put in place as a clear policy by the Commander In Chief before such a conflict were to even begin.

Under this type of “massive retaliation” policy the stakes are immediately much higher for both the adversary and the US, as there are less options on the table for dealing with small-scale use of nuclear weapons by the enemy. Yet at the same time the deterrence factor is considerably higher, which could keep an enemy from trying to use a nuke at all.

Massive retaliation was America’s nuclear policy through Eisenhower’s term in office. JFK changed to the less absolute flexible response model, and although this has kept the mankind from extinction for half a century, there are calls to change this policy in an attempt to adapt to the strategic realities of the new millennium.

In some ways, Russia has already tested NATO’s threshold for military response by invading Crimea. Although Ukraine is not a NATO country, much can be gauged by how the military action was perceived and what measures NATO has put in place following the territorial grab. Although there has been a large increase in US-NATO military drills, especially in eastern European NATO countries, and some assets have been shuffled into the region, they would have a very hard time actually staying off an onslaught from the reawoken Russian bear.

When it comes to the Baltic States, which are NATO members, estimates regarding how long it would take Russia to fully seize Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are not promising, with most numbering just a matter of a few days. If such an event were to occur, Russia could very well threaten nuclear war if NATO attempted to respond conventionally in a major way. They could even initiate a first use of a tactical nuclear weapon in an attempt to freeze the conflict and maintain their territorial gains, just as Admiral Parode described. In fact, Russia has tactical ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons placed in the heart of Europe already.

All this nuclear weapons talk is especially relevant during a Presidential election year, one where the candidates have had some interesting things to say on the issue. Trump in particular has talked a lot about nuclear weapons, and raised a lot of eyebrows in the process. From not knowing what the nuclear triad is to his first debate with Hillary Clinton where he said that he is against first use while at the same time saying that he won’t take anything off the table.

The hard truth is that the next President of the United States will have to decide how to move forward with modernizing America’s rapidly aging nuclear arsenal, a highly complex initiative that will cost hundreds of billions of dollars. Hillary already has some opinions about this, including being against a new nuclear-tipped cruise missile, while trump has mentioned how old the arsenal is (and has slammed the B-52 incorrectly in the process) but has not offered any details as to how he would modernize it.

Meanwhile, Russia is modernizing its nuclear delivery systems and has shown signs that it wants to retain the ability to expand its arsenal quickly in the future by withdrawing from a key nuclear material disposal pact just yesterday. Putin’s reasoning for doing so? “The emergence of a threat to strategic stability and as a result of unfriendly actions by the United States of America towards the Russian Federation.” The agreement, which was executed in 2000 and renewed in 2009, dealt with disposing of enough nuclear material to create 17,000 nuclear weapons.

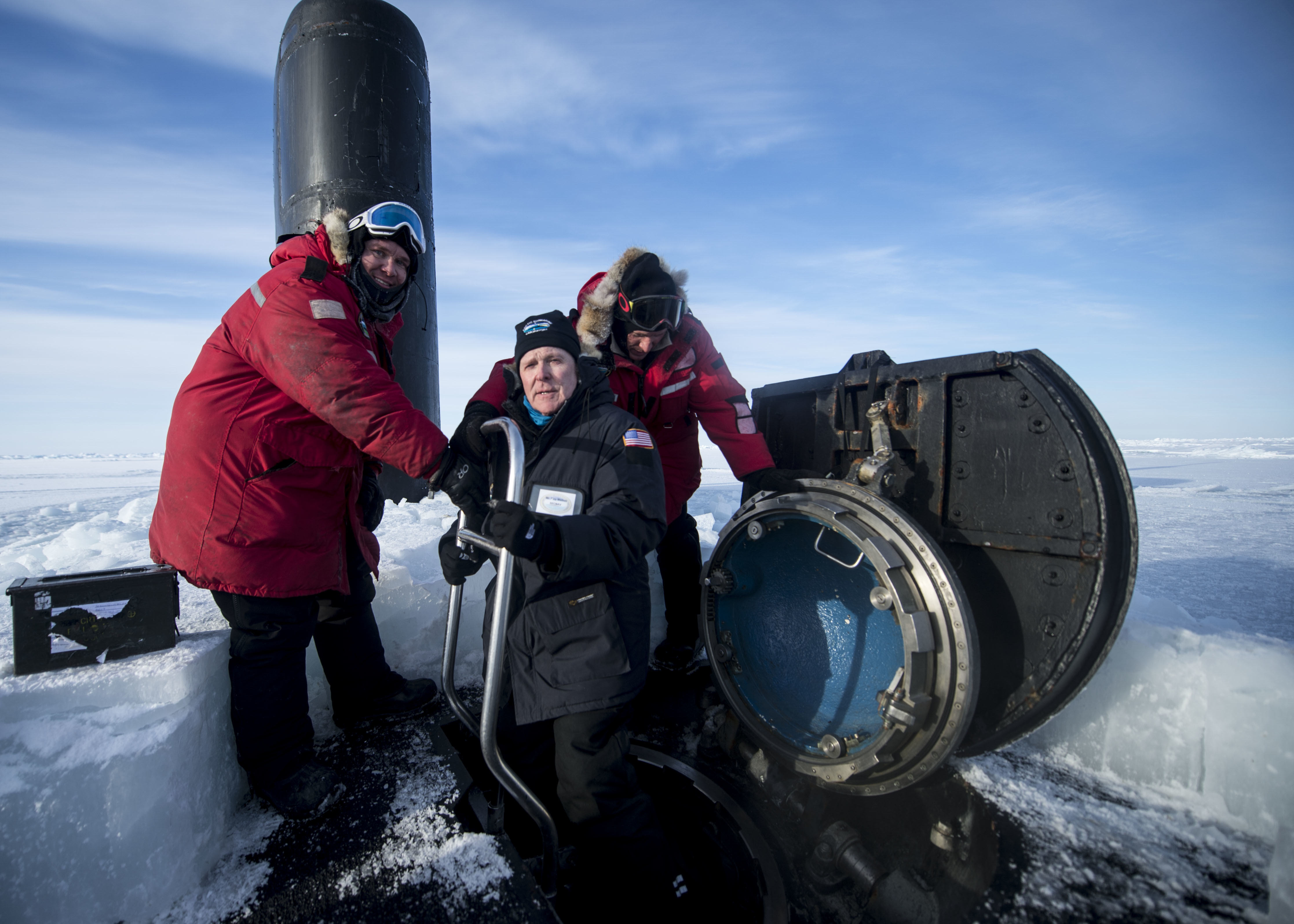

In another segment that aired just this week, Leslie Stahl ventured to the arctic during ICEX 2016. The Navy-led exercise dealt with a whole host of issues, from testing new ways to detect submarines under ice-caps to climate change, but it was really set against a looming possibility that the arctic may be a future battleground.

Watch Leslie Stahl’s segment on ICEX 2016 here.

Russia has been preparing to fight in the far north for years now, and the US is just catching up. As the ice melts new strategic waterways will emerge, ones that can cut down shipping times dramatically compared to some key existing routes.

Stahl also talked with ex-NATO commander Philip Breedlove about the strategic significance of these routes:

Breedlove: I have heard as much as 28 days decrease in some of the transit from the northern European markets to the Asian markets. That is an incredible economic opportunity. And it could be a very boon— big boon to business around the world.

Stahl: What would it mean if the Russians did gain control over the Northern Sea route?

Breedlove: If the Russians had the ability to militarily hold that at ransom, that is a big lever over the world economy.

Stahl: So tell us in a nutshell what’s happening.

Breedlove: Along that route what we see is Russia upgrading over 50 airfields and ports, 14 of them to be done this year, increasing the number of ground troops, putting in surface-to-air missiles, putting in sensors. That could be used to guide weapons. That could be used to deny access… I think it’s important to understand what the deputy prime minister said, that the Arctic is a part of Russia, that they will provide the defense for the Arctic and that they will make money in the Arctic and that the Western world may, therefore, bring sanctions on them, but that’s OK because tanks don’t need visas. I think it sends a pretty clear message.

Large energy reserves could also place new importance on the region. Yet operating up there is not easy, cheap or predictable, as you will see at the end of the segment. Yet the Navy will find itself in ever more demand in this inhospitable region, something that Secretary of Navy Ray Mabus, who also ventured to the ICEX 2016, knows all too well:

“Our responsibilities are increasing as the Arctic ice melts, as the climate changes. And so the Navy has got to be here, we’ve got to provide that presence and I hope that my presence emphasizes what we do.”

Contact the author: tyler@thedrive.com