After giving us an amazing inside look at flying the F-15E Strike Eagle and how its presence in Saudi Arabia has evolved, Richard Crandall is back. This time he paints an awesomely in-depth picture of what it was like strapping into the cockpit of the legendary F-111 Aardvark during the tumultuous final decade of the Cold War.

Joining the F-111 family

I asked for F-15s, F-16s, F-4s, F-111s, or A-10s on my dream sheet. I then called to change the order to put A-10s over F-111s. The assignment guy at Randolph told me not to worry about it, as a classmate had put F-111s first. In fact, his father had died flying the F-111 in Vietnam. Took off and was never heard from again.

He got the F-111. Well, we both got F-111s and I got the second.

I was not thrilled but I sucked it up and got to it. I went to Holloman AFB for Lead-In Fighter Training (LIFT) in the T-38B Talon. I loved the training! I loved the air-to-air sorties and did okay at it. Sadly, the F-111 was lousy at air-to-air. It had way too high a wing loading, poor visibility, and huge energy bleed-off when turning. It was almost impossible to get above 5 g’s in it, and when you did you had just lost about 200-plus knots in the break turn. Oh well.

From Holloman I went to Cannon AFB to fly the F-111D model. The F-111A model first went to Vietnam in 1968 but was withdrawn quickly after three crashes. It returned in 1972 and was very successful. It was named “Whispering Death” by the North Vietnamese. Most of the U.S. pilots called it the “Vark,” short for its name, “Aardvark.” The Aussies called it “Pig,” which was fitting, as its air-to-air maneuverability was that of a fat pig.

The A model had an all-analog cockpit. The Weapon System Officer (WSO) had to twist dials to change the latitude and longitude to the next coordinate. The pilot would turn to the next heading and hack a watch (or use a running time) while the WSO would change the inertial navigation system (INS) coordinates and then make sure the computed heading/time agreed with the dead reckoning time. All F-111 pilots lived by their stopwatch. You could not fly without it, as the INS died young.

The F-111B model for the Navy was cancelled. Too big, too heavy, and not maneuverable. They got the Tomcat instead. Face it: Tom Cruise in an F-111 just wouldn’t have hacked it for a movie. The Tomcat was a good choice on their part.

The F-111C was for the Aussies. It was an F-111A with three-foot longer wings on each side for better range. Strategic Air Command used the same long wings in the FB-111. It had slightly less allowed g loading, but that wasn’t a big deal as we didn’t pull a lot of g’s very often.

The F-111D model was radical. It had a glass cockpit. This included a multi-function monochrome TV for the pilot and a much bigger one for the WSO. It also had digital computers with a tape to pre-load a planned route. It was a paper tape with holes in it, on a reel—no kidding—but it worked, eventually.

The D model had two terrain following radars (TFRs) built by Texas Instruments, just like all the other F-111’s, but it could use the transmitter/receiver from one TFR to power the attack radar up to a range of 20nm. We used that feature a lot and it was a great benefit, as the attack radar often failed. It also had a great Doppler navigation system tied into the INS. This was awesome for overwater flight to keep the INS on track. This was a very difficult system to maintain, and eventually it was canned. It also had a moving map, which was great, but of course that, too, was difficult to maintain, and eventually canned in the ’80s.

The truth is that the D model didn’t work. They parked every single one of them in Fort Worth for several years as they worked to fix the bugs. Meanwhile, they built the F-111E, which was basically an F-111A with bigger air inlets. It was all analog, just like the A model, but It worked.

They then built the F model, which was the Cadillac of the F-111 force. It had huge engines and could even go slightly better than one-to-one thrust-to-weight ratio when almost dry and without stores. It was fast and digital, but not as integrated and as fancy as the D model. No multi-function displays, but it did have digital computers. Eventually, they put the Pave Tack laser targeting system into the F-111F and it carried it internally, which was much better and had less drag than on the F-4, where it was called “Pave Drag.” The F model was most famous for the raid on Gaddafi.

Really low and really fast

The F-111 worked in Vietnam because it flew really low and was really fast. It could fly down to 200 feet AGL (above ground level) using terrain following radar in all but the heaviest rain. As long as the TFR could see the difference between the weather and the ground, it could fly safely.

The Vietnamese would barely hear it coming as it was pushing the mach and was really low, hence the nickname. That tactic, low and fast, became THE doctrine until the third night of Desert Storm. The phrases “speed is life,” “one pass, haul ass,” and “you do more than one pass in a target area you die” all came from Vietnam.

The radar was the best in the fighter world at the time. An F-111 WSO would use the great real beam map from the radar to update the INS and navigate, but also clear the terrain ahead of the jet. If an aircraft is below a mountain peak the shadow behind the peak diverges; if an airplane is above a peak the shadow converges. Thus, the WSO would clear out to much farther range than the pilot could see on his display.

The pilot had a logarithmic presentation of the ground that was weird: level ground would start high on the far right at the greatest range displayed, and then curve down and left in a sort of parabolic curve. The first half of the scope, from left to the center, was one mile. The next half of the scope, from the center to three quarters, was another mile. Then, from three quarters to seven eighths of the display was another mile, from seven eighths to fifteen sixteenths was another mile, until finally hitting ten miles at the far right edge of the display. Thus, the pilot could see terrain fairly clearly from the nose to about three miles or so. After that it all tended to blend in.

The terrain following radar was tied into the autopilot, or you could get a manual steering bar and hand-fly it. We used the auto pilot most often, as when chasing the needles (steering cues) we would tend to get focused only on the needles and would not be cross-checking our other instruments as well as when we monitored the system with the autopilot flying it. It was just safer to use the autopilot, as I was able to have a lot more situational awareness of what was going on.

I learned to do manual TFR without the TFR computer working, which is called raw data TFR. I was comfortable going down to around 500 feet doing that, although I only practiced the technique during the day in Visual Flight Rules conditions, as it was truly a no-kidding, combat-emergency-only technique

During normal operations the WSO would call the terrain down until the pilot called he had the terrain and then the WSO would listen as the pilot would verbalize the climb for the terrain, when they were clear of it, and then “painting out to xxxx miles.” The WSO would then call the next terrain in. So you always had two people cross-checking terrain using two independent systems. It was pretty safe, actually.

The lights in the cockpit were pretty bright. We had no forward-looking infrared picture at all. The F model did have the Pave Tack pod for the WSO to target with, but that wasn’t used to see the terrain normally. The pilot had no way to see the Pave Tack video in the F model. Sometimes we would be flying low through the mountains of New Mexico or southwest Texas and the jet’s external rotating beacon would flash off the terrain that we were flying by and it would seem to be right next to the wingtip. Some aircrew would turn it off as it unnerved them.

In the D model, the pilot could get distracted and see the radar, since it was a flat screen with no hood around it. That was not good to do though. The pilot needed to stay focused on the TFR and not sight-see on the radar scope. A quick story about distractions in the cockpit, especially in the two-man side-by-side cockpit of the F-111:

When I went through training at Cannon AFB my instructor pilot was Fernando Ribas, the pilot who died during Operation Eldorado Canyon (the raid on Libya) along with Paul Lawrence, a great WSO I flew with several times at RAF Lakenheath in the F model.

On one instruction flight, our aircraft had a failure on the multi-Function Display. Fernando—remember, he was a pilot, so think dog-watching-TV here—had to press four buttons and hold them in to get a radar sweep in Narrow Sector Expand. This was the best mode to use for air-to-ground targeting. He had to use both hands to do this. We were at 1,000 feet and were cleared hot at the Melrose Bomb Range located about 25 miles West of Cannon AFB as the crow flies.

When he tried to move the cursor using the goat turd (the cursor control looked like a goat turd and worked on pressure) there was no physical motion and he would lose the radar picture. He wasn’t going to give up. It was fascinating to watch: he would get a picture holding the buttons in, then release it and move the cursor, then push the buttons again. Amazingly, he found the target and had it nailed! Time ran down and we get a “no spot” call from the Range Control Officer. Yep, I forgot to pickle (hit the trigger to release the weapon)—I was having so much fun watching him that I didn’t do my job.

Fernando was from Puerto Rico and had a strong accent. I had taken Spanish in high school and I grew up in a town that was at least 30 percent Mexican-American and had lots of friends and coworkers who spoke Spanish. That night I heard words that I never before heard in my life. If we would not have been on auto pilot we would have died as I shrunk down to about two inches high in shame.

This taught me a lesson, though. Keep your mind on the job and don’t sight-see.

Bombs, bombs, and more bombs.

The WSO was far more important for mission accomplishment in the F-111 than in any other aircraft. We were the night fighter for the USAF. When everyone else was grounded for weather, we flew. No illumination flares needed, just get the radar working and away we go. TFR breaks? Who cares. We had minimum en route altitudes planned for each leg and routinely flew nighttime low levels in the mountains, using them as our TFRs broke a lot. As long as the Attack Radar had a picture, we would find the target.

Our inertial navigation system was nice, but we trained to use dead reckoning and basic radar scope interpretation to get to the target even without the INS. We had backups to the backups to the backup. INS dead? Build a wind model and use the computers without the INS. That doesn’t work? Use a radar timed release based on a fixed angle offset. We practiced them all and got good at them all.

We also carried a ton of bombs. My favorite was laser guided bombs (LGBs), of course, but those were only in the F model. The D model could do them and I practiced a couple of times with an F-4 buddy-lasing the target, and did a bunch with troops using ground-based lasers. Still, my favorite was really the ballutes.

The MK-82 snake eyes used in Vietnam tended to fail if released above 450 knots. We didn’t like to be below 480 knots. Remember, speed is life. I preferred 540 knots. Slick bombs have a huge blast radius and we had to climb pretty aggressively to avoid fragging ourselves when releasing them down low. The solution was the BSU-49 and BSU-50. They basically had a parachute-like balloon that would inflate even at supersonic speeds and retard (slow via drag) the bomb safely behind us. Of course, if they didn’t inflate you had problems. If I remember right, we would still do a safe escape maneuver in case they went “slick” and failed to open.

If you watch the footage of the aircrew that hit the IL-76s on the ground in Libya, only one crew out of six succeeded. You will see two of the bombs flash through the targeting video slick. Thankfully, the crew made it back fine and destroyed two and damaged two of the transports.

Fast forward to 4:52 to see the Pave Tack footage of the strike:

During daytime I had backups, too. For dropping LGBs, if the INS failed, I would use dead reckoning to get to the target, climb to 2,000 feet or so, and have the WSO put the Pave Tack Pod to “snow plow” (looking straight ahead). I would pickle on the target and the WSO would then track the target, designate it and guide the bomb in.

For a loft attack I would have visual timer reference points to the pull-up and then to a manual release. Some of the more elaborate toss and loft release profiles wouldn’t work that well during wartime, unless you were releasing a nuke. Even with 24,500 pounds of bombs you are not likely to hit a target, but for an exercise by golly I would get my bombs off the airplane and at least scare the gophers somewhere near the target area!

The F-111 was a very good bombing platform. It was extremely stable. We had a pilot that was a year ahead of me who became a Weapons School grad, he won the Gunsmoke gunnery and bombing competition and beat out the new F-16s using manual bombing in an F-111E.

I was not that good. However, I got really good at killing the drift and calculating the offset. We would then be releasing a string of bombs, a minimum of four and often up to 20 or 24 (20 let us sweep the wings back farther than 24 did). I could almost always put the string right through the target. Maybe not the middle bomb, but the target would be hit.

Some of the F-111 guys I flew with had been F-100 pilots in Vietnam. They would get down into the weeds dropping Mk-82 snake eyes, pickling them off while in a ten degree dive while really, really low. They said they could pick the window they wanted the bomb to fly through.

When I was at RAF Lakenheath we deployed to Incirlik Air Base in Turkey for a Weapons and Tactics training. It was great flying and a fun time. On the flightline were tons of F-100s. When I walked down it with our Ops Officer he would say “flew than one, and that one, and….”

One of our guys went to Konya Range on the ground as a range control officer and got to know the Turkish F-100 pilots there. One of them showed him his Martin Baker coin that he got for successfully ejecting from an F-100. The F-111 pilot said “wow, that’s really unique!” The Turkish pilot turned to the bar and shouted out “hey guys, show him your coins!” Almost every single one of them had one. Ouch!

Nukes and the one-way plane ticket to Armageddon

F-111 and nukes. We all trained for it. We all were willing and ready for it. I feel—personal opinion, not based on a poll—that most of us expected it to occur in our lifetime. We all got good at it and there was always a group of F-111s loaded out and in the alert facility in the middle of RAF Lakenheath ready to do the deed if called upon.

We knew we had about 15 minutes, max, to get airborne—and possibly less, as that was the flight time for Russian submarine-launched nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles that would target the base. All of the families living near the airfields in East Anglia would be toast.

To get airborne we had to respond fast. When I first got to RAF Lakenheath as a young Lieutenant we had four door Dodge pickups with the HUGE V8s. Massive horsepower and four-wheel-drive as well as lights and sirens. When the klaxon sounded, that thing would scream. We would go flying down the taxiway using fingers as the password. If the number of the day was seven and the military police held up three fingers you would respond with four and keep flying by. Once at the aircraft you would jump out, climb in, and fire the cart.

The cart was basically a solid-rocket fuel motor that put out a ton of smoke and pressure and was used to spin up the number one engine. You then cross bled the air to the number two engine and fired it up. This all happened very fast.

By this point in the process the WSO had the INS on a fast alignment and we would copy the message. If it was valid, then out onto the taxiway, high speed up to the end of the runway, and then off in full afterburner to end the world.

We all practiced this over and over and over again. Every alert you would at least scramble once, but we would never taxi out of the alert area. Once the wall fell it all came to a stop. Even with terrorism, the world is a far safe place today than it was during the Cold War.

One of the stories told to us by a visiting general was of a volatile time in the Cold War when it was so tense at one of the bases, I think in Spain, that they weren’t supposed to run any exercises. This might have been Torrejon Air Base, which had B-47s in the early ‘60s. They made a mistake and launched to an airborne hold (where jets are armed and waiting in the air for the order to execute nuclear strikes). Evidently, every single pilot thought it was the real thing. They knew they wouldn’t launch unless it was real. They got to the hold point and found out it was an exercise.

The point the general made was that every single aircrew executed—not one balked. They launched while convinced their families were dead, as every base was targeted, but they launched nonetheless.

I was absolutely convinced I would have to nuke a Warsaw Pact nation, as that was about all we could hit with the F-111. We had a couple of targets in Russia where we would have had to recover with emergency fuel at one of the far northern bases in Norway. But really, we all knew the base would be gone and we would have to punch out. We also knew that we would not be the first nuke on the target. Every single target I ever saw had ICBMs and then SLBMs and then us on it, and then hours and hours later, the stateside B-52s and B-1s.

We always practiced World War III as starting conventional, usually with the Russians punching through the Fulda Gap. I remember looking at the plans and seeing that we had a handful of tanks to stop them, compared to thousands of Russian and East German tanks lined up just waiting to punch through. We would fall back, and back, and then stand down, load up the nukes, and then sortie. Exercise over.

The Russians, however, planned to fight through the nuclear war and win. I don’t know how it would have really turned out. Every single one of us was absolutely shocked when the wall suddenly fell and the USSR was no more. In hindsight, it was inevitable.

You go back and read the stories, though, and I don’t think anyone saw it coming. What a relief it was when Germany reunited and we found out Ivan wasn’t ten feet tall after all. Yeah, we knew our stuff was better, but face it—they had a gazillion of their stuff.

Aardvark’s effectiveness

Most of my fellow F-111 aircrews and I were good, and we really felt we would take the target out. But let’s look at the raid on Libya: 24 aircraft launch, several break and return, one crashes. Out of the three targets targeted by the aircraft that made it to the target area, only three aircraft hit the target—one on each target. All the others missed.

It was terrible when I look back on it, but hats off to the crew who flew it! This was even with the Pave Tack pod on the aircraft and with two of the targets being attacked with LGBs, the airport used MK-82s but had the Pave Tack pod to find and designate the target.

The aircrew that hit the airport, hats off to them! I knew the WSO extremely well, a good friend and fellow instructor for several years. In watching his tape, he nailed the radar offset for the airport. The radar was not good at burning out flat concrete but did much better on targets with more radar reflectivity. He went to narrow sector expand mode on the offset and then switched back to the Pave Tack infrared video, and nothing appeared. He went back and checked the offset again, and still dead on. The he switched back to the Pave Tack. Every other aircraft let the bombs fly using the radar offset. Their bombs hit the airfield between the taxiway and the runway. The coordinates on the offset were evidently bad.

My friend went from narrow sector to wide sector in the Pave Tack and in the right side edge of the field of view he caught sight of the IL-76s. You hear him shout “come right come right” to the Pilot who is seeing nothing except tons of anti-aircraft artillery exploding and his TFR screen. The pilot made a hard turn. As he rolls out, his WSO has fired the lasers and the bombs immediately flew off. You see in the video the Pave Tack’s video rotate to upside down due to the mechanics of the pod rotating to see the target behind the aircraft. The WSOs had to learn how to track upside down when guiding LGBs. You then see a huge explosion rip through the airplanes. That was incredible teamwork in the cockpit. Good on the WSO to switch to wide field of view—it went from a really narrow straw to a slightly fatter straw to look through, but got him onto the target.

Mission success.

Fast forward to Desert Storm five years later. Most aircraft on the first night hit their targets successfully. In fact, I think all but the few who turned back due to bad Mode 4 IFF or other maintenance issues hit their targets.

Keeping skills sharp in the F-111 community

I trained for five and a half years in the F-111. I had a little over 900 hours. We just didn’t fly as much as other aircraft did. Our short missions were two and a half hours long. I was getting around 200 hours a year and I had moves, deployments, vacation etc. that cut that down some. Some of our missions would be three and a half-plus hours long, all on internal fuel, no bags (external fuel tanks). The plane had legs, and boy was it fast.

It all worked out to about 90 flights a year. How about that F-16 guy, a bunch of .9 hour or less air-to-air hops, I’m guessing. Let’s be generous and say every sortie was 1.3 hours on average. If they flew the same 200 hours, then they flew many more flights, as the F-16 just didn’t break the way the Vark did. If you do the math, that would equal over 150 sorties a year for the F-16 guy. Guess what? They dropped the same number of bombs, on average, every mission—six from the trusty old SUU-20 practice bomb rack.

In the F-111, we would use two of these practice bombs per mission to keep our radar laydown and toss tactics up to snuff, and the remaining four for visual dive bombing. The F-16 driver, even counting their air-to-air training flights, got way more bombs per year than us. The A-10 guys, it was no comparison. All they did was bomb and strafe, bomb and strafe. Love the A-10.

The F-111’s infamous “dump and burn” maneuver

We had an F-111D from Cannon AFB head out to Canada for Maple Flag in the ‘80s. Everybody did an unofficial “arrival show.” Upon arrival in the overhead pattern the F-16s would pull 9 gs, the F-15s would pull 9 gs, the F-4s would pull 7 gs, the A-10s would pull however many they could. Then again, for the Warthog it didn’t really matter how many gs, as it could turn on a dime. And then there was the F-111.

If really light and pushing .95 mach or so while over-speeding the wings (if wings were swept forward, the jet was mach-limited) you might get 5 gs for a nano-second or so, and then you would be doing about .001 mach. Your awesome break turn would have taken half the state of Texas, too.

The pilot at the center of this story was a great guy. He was a high-time flyer with many thousands of hours under his belt. What was he to do? Sneak in and go hide in the corner of the bar while everyone else bragged? Nope. He came around and leveled off about ten feet above the runway and hit the dump switch, paused, then stroked the burners.

Momentary pause for style points.

Dumping and Torching needed to be in that order. If you torched first and then dumped you ended up with more fizzle and far less flame. For Olympic-class style points, even from the Russian judge, you needed to let the fuel fully aerosolize and then light the cans. The result? A massive stream of fire double the length of the jet pouring out of its tail.

There was Dick, streaking all the way down the runway trailing a wall of flame behind him. Best thing ever next to Napalm! The crowd went wild, but no buying beers for him and his WSO that night. When he pulled up in a closed pattern to land and threw the gear down, he looked at the runway. It was still burning. His fire had lit up all the rubber from the skid marks from aircraft landing!

He really thought he was going to get in trouble but the Canadians loved it. They said it was the best show they had ever seen!

The Vark’s weaknesses and strengths in retrospect

The F-111 was great at low altitude. It did good in Desert Storm, too. Great legs, lots of bombs, and really, really fast! It couldn’t turn worth a darn. That’s okay, and for most of Desert Storm it was fine. It was rightly retired because it was nine percent of Tactical Air Command’s fleet but ate up a whopping 25 percent of the maintenance budget.

Too often I would lose the radar because its mean-time between failure (MTBF) was less than 20 hours or so. Other systems like INS had a MTBF that was far less than 20 hours. When the TFR went out I would end up with a twin engine F-100 and would have to bomb using “iron sights.” Still, it could haul lots of bombs and was stable as all get out.

Weakness? They took the gun out. General Creech, a TAC commander during the F-111 development, was quoted saying he wasn’t going to have a $20 million dollar airplane strafing $20,000 trucks. We could only carry the AIM-9P Sidewinder with no radar cueing, and that was the mid ‘80s before it became routine to have the Aim-9 loaded up at all. The AIM-9P is only going to hit if launched from the rear against someone running hot, and we had no maneuverability to get to the rear of the bad guy. At least the smoke trail coming off my wing after launching the thing might make the other guy flinch, so I could get low and run like a scalded ape.

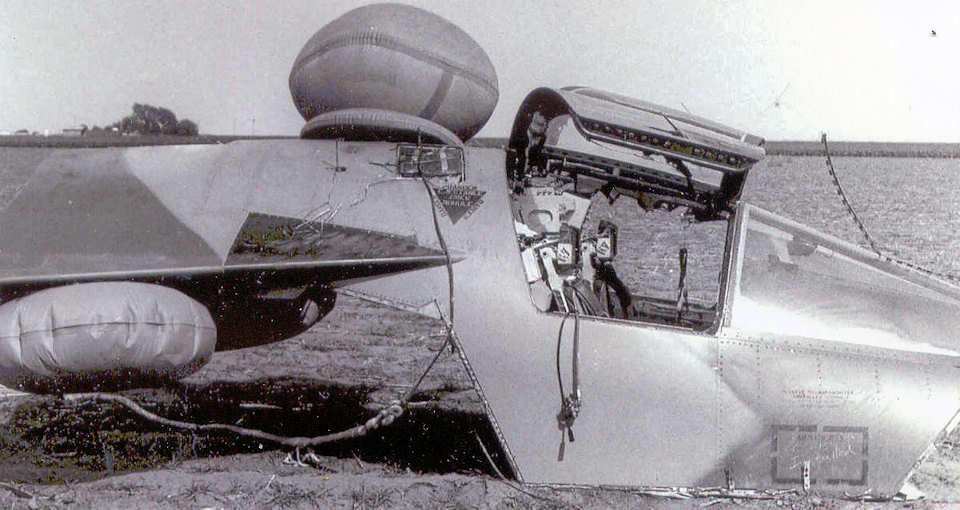

The capsule ejection system was both a weakness and a strength. We had a lot of guys mess up their backs with ejections. A squadron commander at Mountain Home was a paraplegic after ejecting, when the air bag failed to work. We never had anyone die from wind-blast, though. We had several supersonic ejections, no big deal. Plus, when ejecting into the cold ocean, you don’t get wet until they show up to rescue you.

It did take too long to get the chute deployment during ejection, though. It was something like 10 seconds from pulling the handle to the chute deploying. I had an instructor pilot who was my cadet squadron commander when I was a sophomore at the Academy who ejected at Mountain Home when he had a compressor stall doing a break turn at 500 feet above the field. The A model did not have the mod at that time to keep it from departing in yaw when exceeding the max angle of attack. With the loss of thrust he had less than a second to go full forward on the stick to avoid a high speed stall/departure. They punched out too low and both crew died.

The amount of bombs the F-111 could carry was definitely a strength. I have a picture of the F-111C dropping 48 Mk-82s. I think he had to be in full burner to barely get to 10,000 feet. They used fixed pylons on the outboard stations to carry six 500-pounders on each pylon. You can’t sweep the wings unless you punch the pylons off. Totally impractical, but also really cool!

Range was a huge plus for the F-111. I did a four-hour low-level using internal fuel and two weapons bay tanks with no wing tanks. Try to do that in a Strike Eagle or a Viper. Of course, who on Earth in their right mind wants to sit in an ejection seat for 4 hours while flying continuously at low-level?

The Vark’s big strength was that it was fast as hell. I routinely cruised at .95 mach in military power (full throttle with no afterburner augmentation) while on the deck. The F model was nearly super cruise-capable. I saw 1.1 mach on the deck in a D model, and I knew guys who had the F model up to 1.4 mach on the deck! It held enough gas to do it for a while, too. Not many planes could keep up.

Living the swing-wing dream

My favorite memory while flying the Vark remains as vivid in my mind today as the day after it happened. I was flying right at sunset, dropping bombs in the North Sea off of Eastern Scotland. We had a Pave Tack pod but no way to really measure miss distance, but at least we could see the smoke from the practice bombs and if it was close to the target, we could tell. It was kind of like plinking cans with a .22—not really doing much damage but fun nonetheless.

It was completely overcast and very dark under the clouds with marginal visibility. In other words, standard English weather! We were grounded from night flying on the TFR at the time due to maintenance problems. We had several instances, including a fatal crash at night, where the TFR failed in ways the engineers had no idea it could, even though the system was nearly 20 years old by then.

Since we had to knock off at sunset I was watching my clock. By then it was getting really dark under the clouds, especially since we were out over the ocean with no lights anywhere. I waited until the last second and then lit both burners. 54,000 pounds of thrust awoke behind us and I pulled back on the stick to punch up through the clouds.

We weren’t allowed to do any over-the-top maneuvers. No loops, Cuban 8s, Immelmanns, etc. To be legal, I therefore went to 89 degrees of pull instead of 90 degrees. We hit the clouds on our back and punched through very quickly as the layer wasn’t very thick. It surprised me when I saw, upside down, the most beautiful sight I had seen yet while flying: The sun was suspended, half-buried in a field of solid white with a fiery display in the cirrus high altitude clouds still above me. I froze the climb while inverted, still with my nose 45 degrees above the horizon, still in full afterburner, and said to my WSO:

“And we get paid for doing this?!”

A huge thanks to Richard Crandall for sharing his incredible experiences in the F-111 with us.

Contact the editor Tyler@thedrive.com