The U.S. Army says it wants to begin developing a replacement for the venerable Stinger short-range heat-seeking surface-to-air missile and actually begin testing at least one prototype design by the end of the 2023 Fiscal Year. The goal is then to get a finalized weapon into production no later than the 2027 Fiscal Year. This comes as the service has determined its existing Stinger to be increasingly obsolete and as its stockpile of these weapons is shrinking, in part due to transfers to the Ukrainian military to support their ongoing operations against Russian forces.

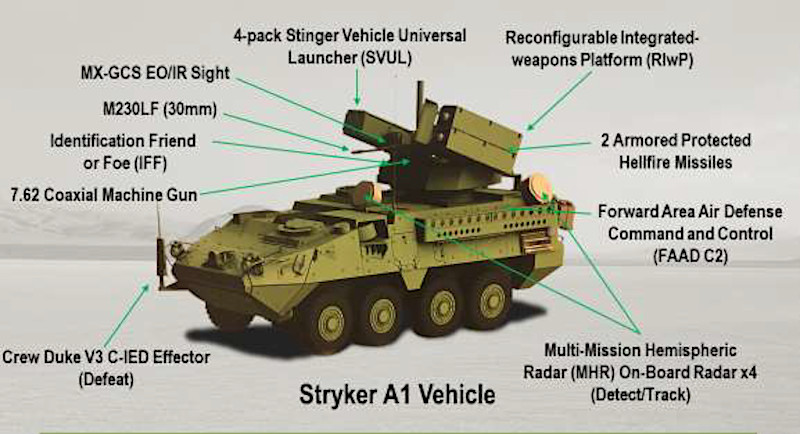

The Army’s Project Manager for Short and Intermediate Effectors for Layered Defense (SHIELD) issued a formal request for information (RFI) regarding the proposed Stinger replacement on March 28, 2022. The replacement effort is officially known as Maneuver Short Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD) Increment 3. M-SHORAD Increment 1 is a mobile short-range air defense system based on the 8×8 Stryker wheeled armored vehicle that is armed with Stinger, as well as millimeter wave radar-guided Longbow Hellfire missiles and a 30mm automatic cannon. Increment 2, also known as the Directed Energy Maneuver-Short Range Air Defense (DE M-SHORAD) system, will be Stryker-based design equipped with a directed energy weapon. The Army is already evaluating on design equipped with a 50-kilowatt class laser, but the service could still potentially consider alternatives, such as one proposed type with a high-power microwave weapon.

According to the March contracting announcement, Increment 3 is simply focused on the development of a new missile to replace Stinger, rather than a new complete vehicle. Details about exactly what the Army might be looking for in a new missile are, so far, relatively limited, but the notice did provide some useful details.

“The system must be capable of defeating Rotary Wing (RW) aircraft, Group 2-3 Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS), and Fixed Wing (FW) ground attack aircraft with capabilities equal to or greater than the current Stinger missile (with Proximity Fuse capability),” it said. “The system must provide improved target acquisition with increased lethality and ranges over current capability.”

The U.S. military defines Group 2 drones as types having maximum weights between 21 and 55 pounds, an operational ceiling of no more than 3,500 feet, and that fly at speeds of 250 knots or less. Group 3 types also cannot fly faster than 250 knots, but can have a maximum weight of up to 1,320 pounds and are able to reach altitudes of up to 18,000 feet.

“The system must be capable of integration with the Stinger Vehicle Universal Launcher (SVUL),” the contracting announcement adds. “The system must be a soldier portable All-Up-Round (AUR).”

The SVUL is a four-round launcher used on the M-SHORAD Increment 1 vehicle and the Avenger system, which can be mounted on a 4×4 Humvee or in a static position. This all strongly indicates that the Army wants any new missile to be readily compatible with existing vehicle-based Stinger launch architecture, as well as man-portable launch units.

“The Stinger Reprogrammable Microprocessor (RMP) will become obsolete in fiscal year (FY) 2023 and Stinger Block I is undergoing a service life extension to extend its end of useful life,” the notice said as part of an explanation of why a new missile is needed now. “The current Stinger inventory is in decline.”

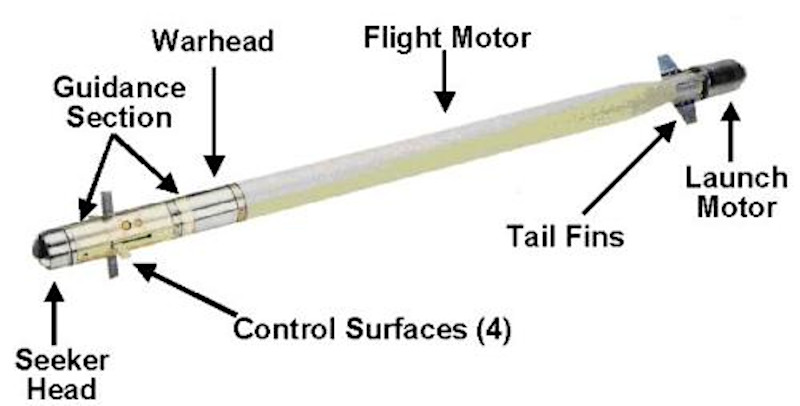

Stinger’s origins go all the way back to 1967 with an Army requirement for a successor to the FIM-43 Redeye, its first-ever shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile system, also known as a man-portable air-defense system (MANPADS). Active development of what was originally known as the Redeye II and redesignated FIM-92A began in 1971.

Various issues encountered in development meant that Army only awarded the first contract for mass production of what had been renamed the Stinger to General Dynamics in 1978. The service began fielding the weapons in 1981. Stinger, of course, famously saw its first combat use in the hands of rebels in Afghanistan, who used it to great effect against Soviet forces in the country in the 1980s.

In 1983, production of the FIM-92B, with an improved seeker, began. The following year, development started on the first Stinger RMP variant, the FIM-92C, which, as its name implies, included a reprogrammable microprocessor designed to make it easier to integrate software improvements going forward. General Dynamics stopped making FIM-92A and B missiles in 1987 when it shifted its entire production line to the much-improved FIM-92C. An upgraded FIM-92D variant designed to better resist enemy countermeasures was subsequently developed.

In 1992, General Dynamics received a contract to develop an improved RMP variant, known as the RMP Block I or FIM-92E. Shortly thereafter, General Dynamics sold its missile division to the Hughes company, which then finished work on the new Stinger version. The Army received its first FIM-92E missiles, which featured improved seekers and updated software that reportedly gave them improved capabilities against targets with smaller infrared signatures, in 1995.

The FIM-92F was a further upgrade of the FIM-92E missile, while the FIM-92G was an updated FIM-92D type. The Army ultimately brought a number of FIM-92Ds up to the full Block I standard, redesignating them as FIM-92Hs.

Since around 2014, the Army has been working to put RMP Block I missiles through a service life extension program that also includes a number of upgrades, notably the addition of a proximity fuze that improves the weapons capabilities against smaller targets, such as drones. This work was largely driven by changes in various threat assessments prompted by Russia’s seizure of the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine and its subsequent support for separatists in the eastern Donbas region, events that presaged the current conflict there.

These upgraded missiles are known as FIM-92Js. There is also a subvariant of that missile, known as the FIM-92K, which is designed for use in vehicle-mounted launch systems and that uses a built-in datalink to at least receive initial targeting information from the launch platform, rather than rely on its own seeker. This concept is widely known as lock-on after launch (LOAL).

Between 1996 and 2002, the Army had funded the development of a more significantly upgraded RMP Block II missile, with an expanded operating envelope of up to 26,000 feet, among other improvements. However, the program suffered significant delays and when it was finally canceled production of the missiles was already five years behind schedule.

So, as the Army’s contracting notice in March pointed out, all of these missiles that are still in service are based on the core RMP and RMP Block I designs from the 1980s and 1990s. The FIM-92J upgrade program does add 10 years to the shelf life of these updated Stingers, but the service hasn’t bought any new production missiles for itself in years. It’s also worth noting that the Army is the central manager for the Stinger program across the entire Department of Defense, and other branches, like the Marines, haven’t been ordering new missiles, either.

This means that the existing Stinger stockpiles have slowly been dwindling over the years just due to normal training and test and evaluation requirements. That inventory has only contracted more recently as the U.S. military has transferred thousands of these missiles to Ukraine to bolster its air defense capabilities amid the ongoing war with Russia, something that is likely to continue at least in the near term.

Sending Stingers, as well as other weapons, to Ukraine has prompted broader discussions about how much effort it might take to replenish these transferred stocks, or surge production in general for any other reason, as you can read more in this recent War Zone piece. It has also raised questions about whether this is might be a prime opportunity to move on to new systems, such as a Stinger replacement.

“There is nothing preventing the United States from helping our friends in Ukraine with Stingers and Javelins,” Donald Norcross, a Democratic Representative from New Jersey and the Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee’s Air and Land Subcommittee recently told Defense News. “What I also want to bring into the conversation is many of those weapons that we’re talking about are of a design of decades ago. Is it the best use to reengage those lines or to upgrade?”

The Army seems to be of the view that now is the time for a Stinger replacement. However, the service’s stated form factor and schedule goals do raise a possibility that another significantly improved Stinger derivative could meet its requirements.

Advances in the past decade in miniaturized multi-mode seeker systems, warhead technology, and high-grain rocket propellant could potentially combine to form a missile that has a significantly expanded engagement envelope against a broader set of targets than existing Stingers, but in a package with exactly the same dimensions. Improved networking capabilities could be used to link a future Stinger derivative, as well as any new clean-sheet missile design, or its launcher to a variety of offboard sensors to help with target acquisition, cueing, and engagement. A design with a multi-mode seeker combined with a data link, even an optional one, capable of feeding in additional targeting information could not only be more accurate and flexible, but also more resistant to enemy countermeasures.

Regardless, what is clear, as the current conflict in Ukraine has further underscored, is that advanced short-range air defense (SHORAD) capabilities will be extremely important for the U.S. Army, as well as other branches of America’s armed forces, going forward. The threat posed by small drones, which is real now and only continues to grow, has already shown the need for improved SHORAD systems, and more of them. Though improvements are being made, the U.S. military, as a whole, remains woefully behind the curve when it comes to bolstering its arsenal in this regard, as you can read more about in this past War Zone feature.

All told, it will be very interesting to see how this Stinger replacement effort evolves, especially with the Army hoping to have begun actually testing a prototype design before the end of next year.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com