The U.S. Army has released a new strategy for how to adjust its operations in response to climate change while still executing its core mission to “deploy, fight and win our nation’s wars by providing ready, prompt and sustained land dominance.” As part of that strategy, the service released a report outlining how the Army can adapt its installations, acquisitions, supply chains, and training in order to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. However, questions remain about how these plans will be funded in both the long- and short-term.

The 20-page “Climate Strategy” report, published this week by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Installations, Energy and Environment, can be found online. The document is organized according to three “Lines of Effort” the Army has identified: Installations, Acquisition and Logistics, and Training. Under each of these, the report lists specific objectives and timelines for how to achieve its “End State and Goals” for the new Climate Strategy.

The end goals of the Army’s climate strategy include:

– Achieving 50% reduction in Army net greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to 2005 levels

– Attaining net-zero Army greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

– Proactively considering the security implications of climate change in strategy, planning, acquisition, supply chain, and programming documents and processes

In a foreword to the report, Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth says climate change is already impacting supply chains, infrastructure, and posing increased health risks to soldiers and their families in the form of extreme weather and natural disasters. To mitigate these effects, Wormuth writes, the service must “purposefully pursue greenhouse gas mitigation strategies to reduce climate risks” throughout the entire Army enterprise. “If we do not take action now,” Wormuth adds, “our options to mitigate these risks will become more constrained with each passing year.”

However, while the Army’s new climate strategy document offers meaningful changes that could have global impacts, there are already questions being raised about how the service will pay for the wide-ranging initiatives outlined in the report. “We’re working through the funding,” Paul Farnan, the acting assistant secretary for Army installations, energy, and environment told reporters this week, according to Defense One. “The funding is going to be a moving target. This is a strategy that lays out steps…a lot in the coming decade, and even some beyond the next decade. We’re going to be creative,” Farnan added. “We’re going to look at every way to stretch the dollar.”

The Army’s document lists a variety of primary and secondary impacts on the service’s operations that climate change is causing or will likely cause in the future based on current trends. These include increased water scarcity, flooding, or land degradation at Army installations; impacts to soldiers’ health caused by exposure to smoke, dust, disease vectors, or temperature extremes; and “an increased risk of armed conflict in places where established social orders and populations are disrupted,” among others.

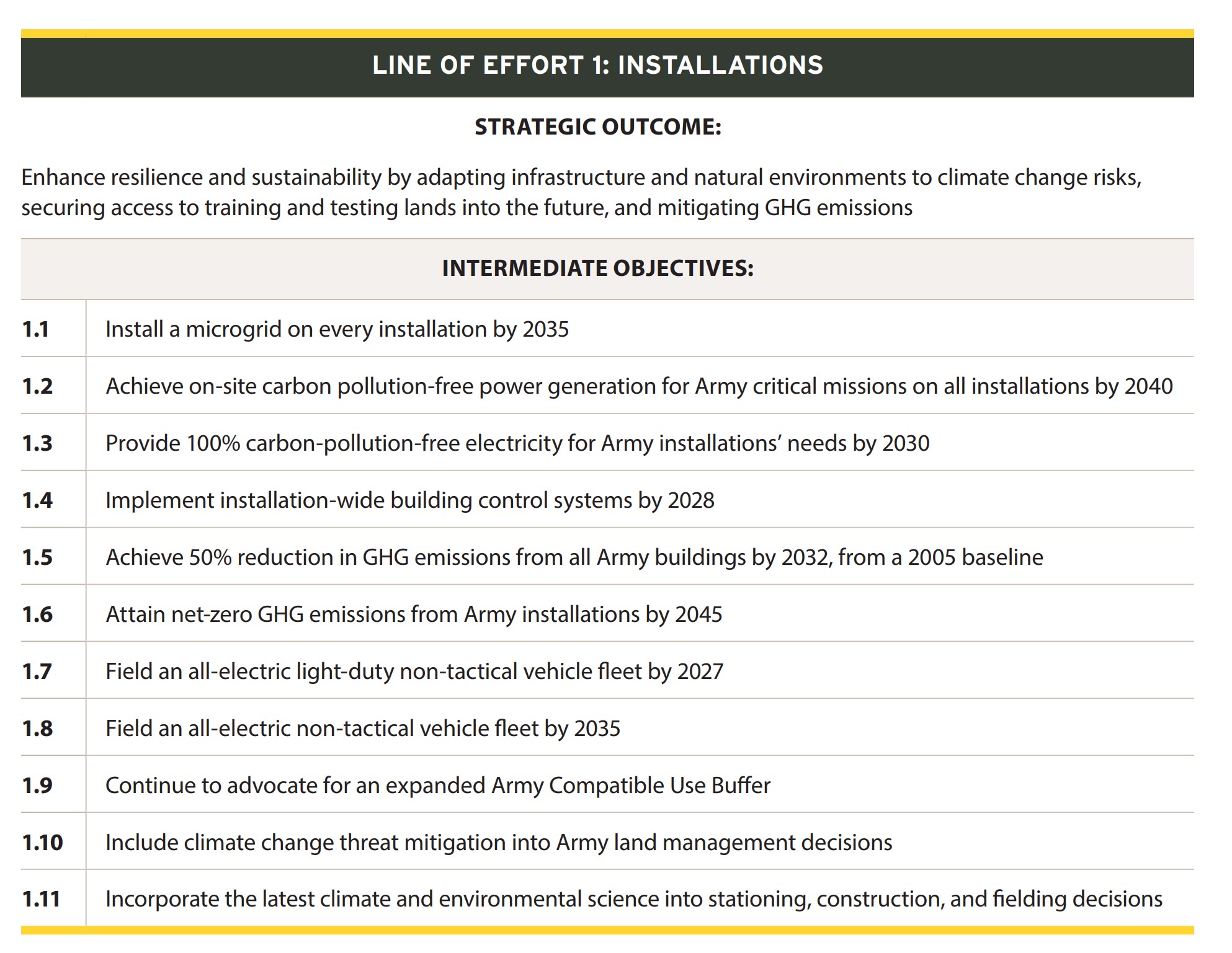

The report states the Army operates over 130 installations worldwide, and the first line of effort in the service’s new strategy is aimed at enhancing the resilience and sustainability of these facilities. While the document points out that the Army has reduced its overall greenhouse gas emissions from its installations by 20% since 2008, the service has now committed to the ambitious goal of powering these facilities with 100% carbon-pollution-free electricity by 2030.

Carbon dioxide accounts for the vast majority of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the Environmental Protection Agency reports that burning fossil fuels for electricity, heat, or transportation is the largest contributor to these emissions. According to numerous studies, the U.S. military consumes more fossil fuels and emits more carbon dioxide than many entire countries.

The Army’s specific goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from its installations include developing more resilient energy and water supplies, moving towards carbon-pollution-free methods of producing electricity, improving the energy efficiency of Army structures, electrifying the service’s non-tactical fleet of commercially available vehicles, and improving land management and planning. A key part of this strategy is the installation of a “microgrid” at every one of its installations by 2035 in order to minimize base fuel demands.

The objectives and timelines for this line of effort can be seen in the table below:

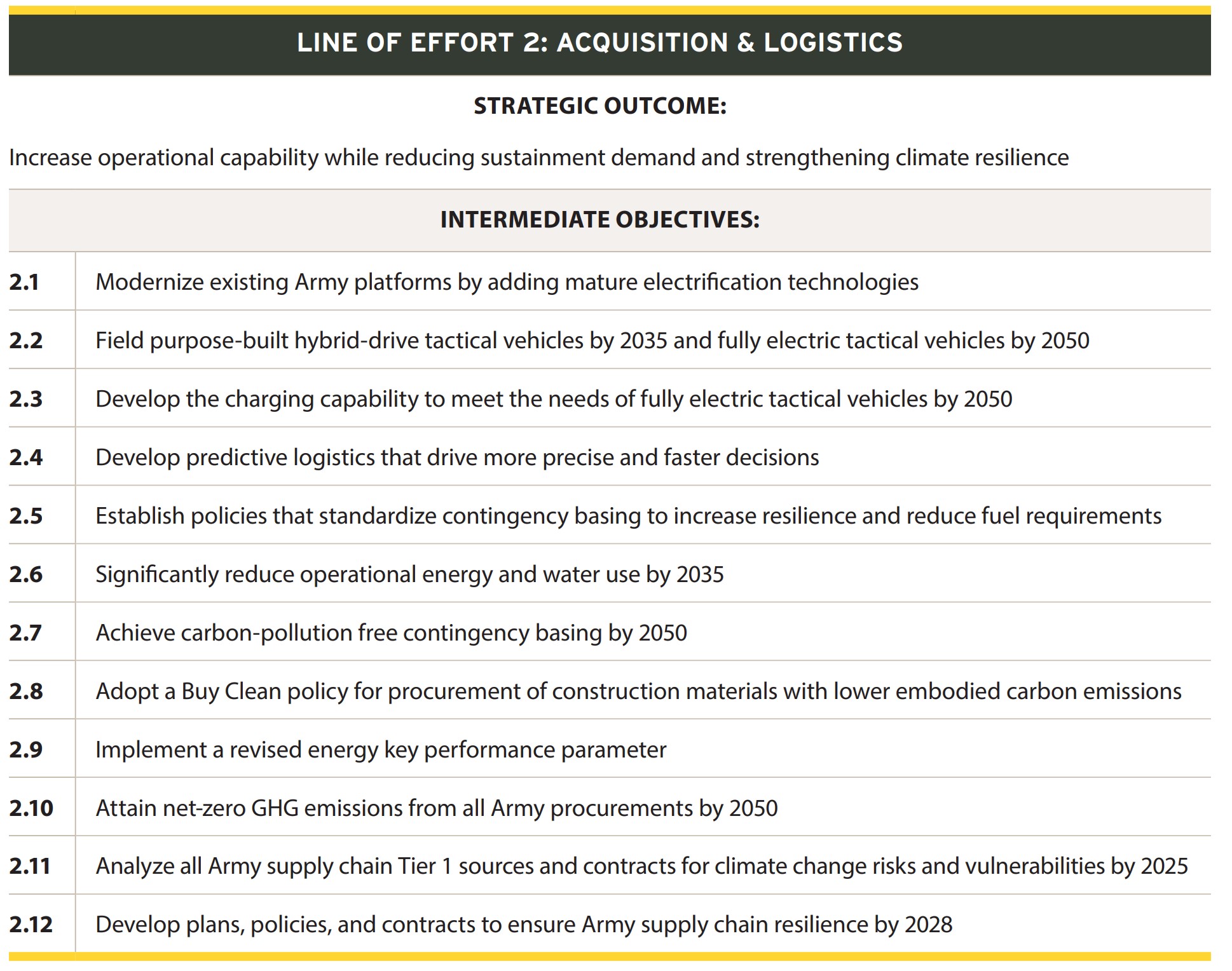

The Army’s second line of effort, Acquisition & Logistics will attempt to “increase operational capability while reducing sustainment demand and strengthening climate resilience.” To achieve this, the service plans to invest in new advanced technologies and optimize the efficiency of its supply chains and distribution networks. According to the climate strategy document, the Army “sees great promise for sustainment demand reduction through advanced technology, future contingency basing, clean procurement, and resilient supply chains.”

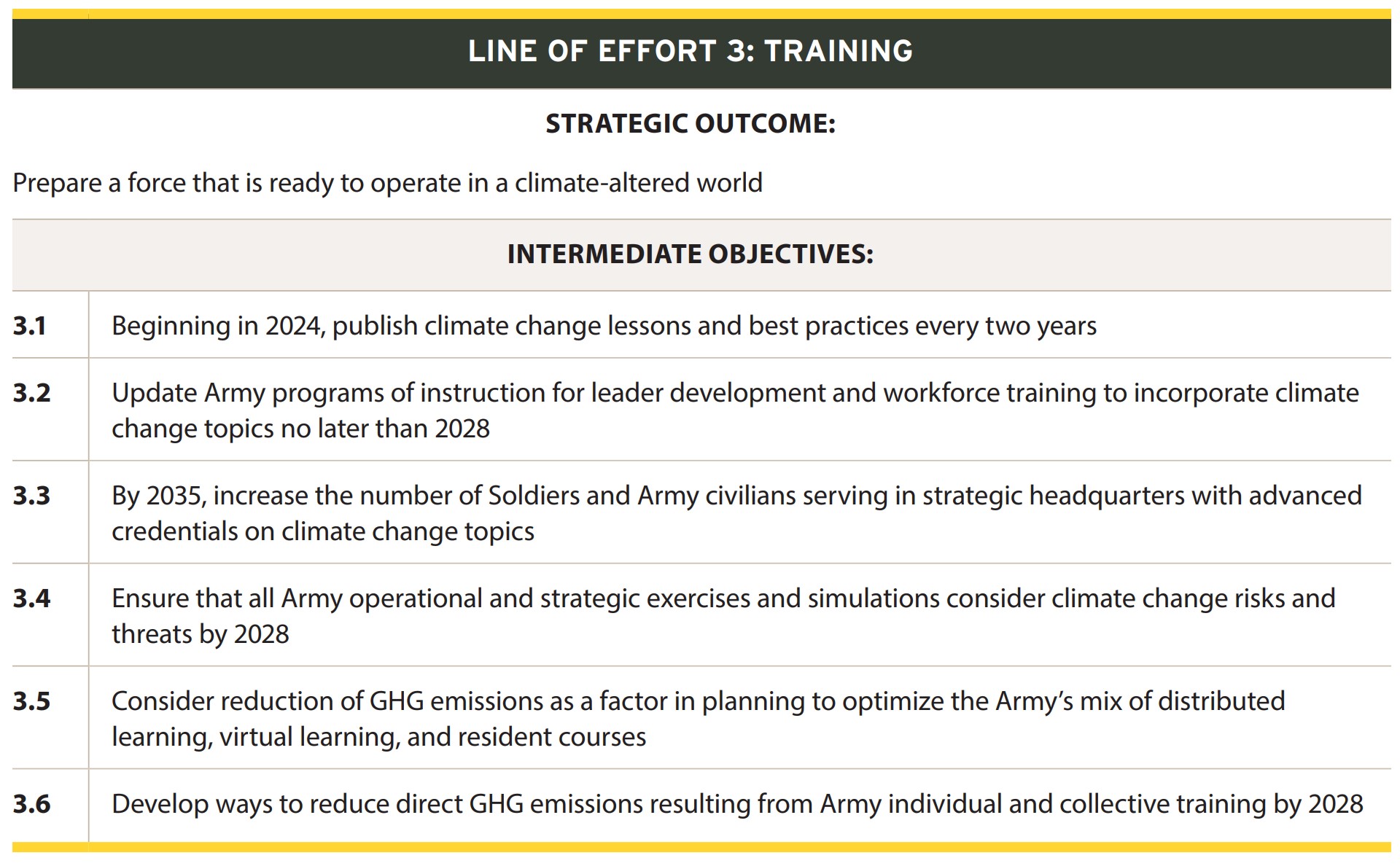

Finally, the Army plans to adapt its training so that it can better prepare soldiers to operate in a climate-altered world while simultaneously maintaining its combat effectiveness. “Such preparation requires shifts in what and how the Army trains its people, units, and headquarters,” the climate strategy document states.

To make these shifts, the report says the Army will publish “climate change lessons learned and best practices” every two years beginning in 2024. By 2028, the Army will implement “climate-informed” programs of instruction, and by 2035 will increase the number of service members and civilians serving in strategic positions with “advanced credentials on climate change topics.”

Some of the specific climate-oriented training directives include prioritizing distributed or virtual learning when possible and developing ways to reduce GHG emissions directly resulting from Army training events. The report makes it clear that the service “will not simply cancel training or other readiness-generating activities to mitigate climate change.”

We have already seen prototypes and incremental developments related to some of the report’s recommendations in recent years. Several leading Army contractors have already pitched the service on cleaner vehicle technologies such as GM’s hydrogen-powered 4×4 platform or a new hybrid electric version of the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle shown off earlier this year. While none of those has yet to enter service, the Department of Defense (DOD) is also looking into a number of ways to make its existing fleets of vehicles more fuel-efficient.

The Pentagon is even looking into more exotic, long-term solutions such as beaming solar energy from space and funding research and development into nuclear microreactors that might one day help offset the DOD’s massive fuel usage.

To underscore the importance of the Army’s new climate strategy, the document cites concrete examples of how climate change is already changing the strategic landscapes, both literal and figurative, in which the service operates:

For example, the Arctic is warming twice as fast on average as the rest of the world, and disappearing sea ice is opening new trade routes and access to new natural resources, inviting greater strategic competition. In regions across the globe, these changes foreshadow the demanding environmental conditions in which Army forces must be prepared to operate.

We have already seen this shift occurring in the Arctic, where Russia is expanding its presence and infrastructure as receding polar ice has allowed Russian forces to operate more regularly throughout the region. Aside from altering the global landscape, climate change is forecasted to lead to an increase in extreme weather events, the likes of which have caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to the headquarters of U.S. Strategic Command and devastated Tyndall Air Force Base in recent years.

Wildfires in the western United States in recent years have also prompted the U.S. military to divert personnel and resources away from missions or even forced the evacuation of bases or cancellation of training events. These fires were in many cases exacerbated by droughts, which have put more than 100 U.S. military bases at risk of water scarcity, according to a 2019 study by the Government Accountability Office. U.S. Navy facilities are also facing increased complications stemming from sea level rise and an increased prevalence of extreme storms, both of which are caused or exacerbated by climate change.

Meanwhile, a 2021 study published by Office of the Director of National Intelligence stated that while climate change is rarely the primary driver of instability and conflict, “certain socio-political and economic contexts are more vulnerable to climate sparks that ignite conflict.” It’s possible that if steps aren’t taken worldwide to mitigate climate change, conflicts could become more prevalent in areas hit hardest by the effects of climate change.

The Army’s new climate strategy comes after the White House signed an executive order in January 2021, “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad,” which called on federal agencies including the DOD to make climate change a key priority in all strategy and planning documents. Nine months later, the Department of Defense published its “Climate Adaptation Plan” which, similar to the Army report published this week, stated that climate change will “continue to amplify operational demands on the force” and “increase health risks to our service members.”

While the Army’s climate strategy document lays out an ambitious plan for how the service can help mitigate its impact on greenhouse gas emissions, the document does not prescribe specific policies or actions. It will be up to the wider service to find ways — and funding — to enact the strategy moving forward while maintaining its core mission.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com