The U.S. Army’s Ground Vehicle Systems Center, GVSC, has announced a successful demonstration of a new system designed to defend ground vehicles against cyber attacks. Because a large portion of the service’s vehicle fleets were designed well before the advent of modern cyberattacks, their systems remain vulnerable to these threats. According to the Army’s announcement, the demonstration proved “the need for robust cyber defensive technologies in legacy and future ground vehicle systems” in order to “ensure cyber survivability and augment force protection.”

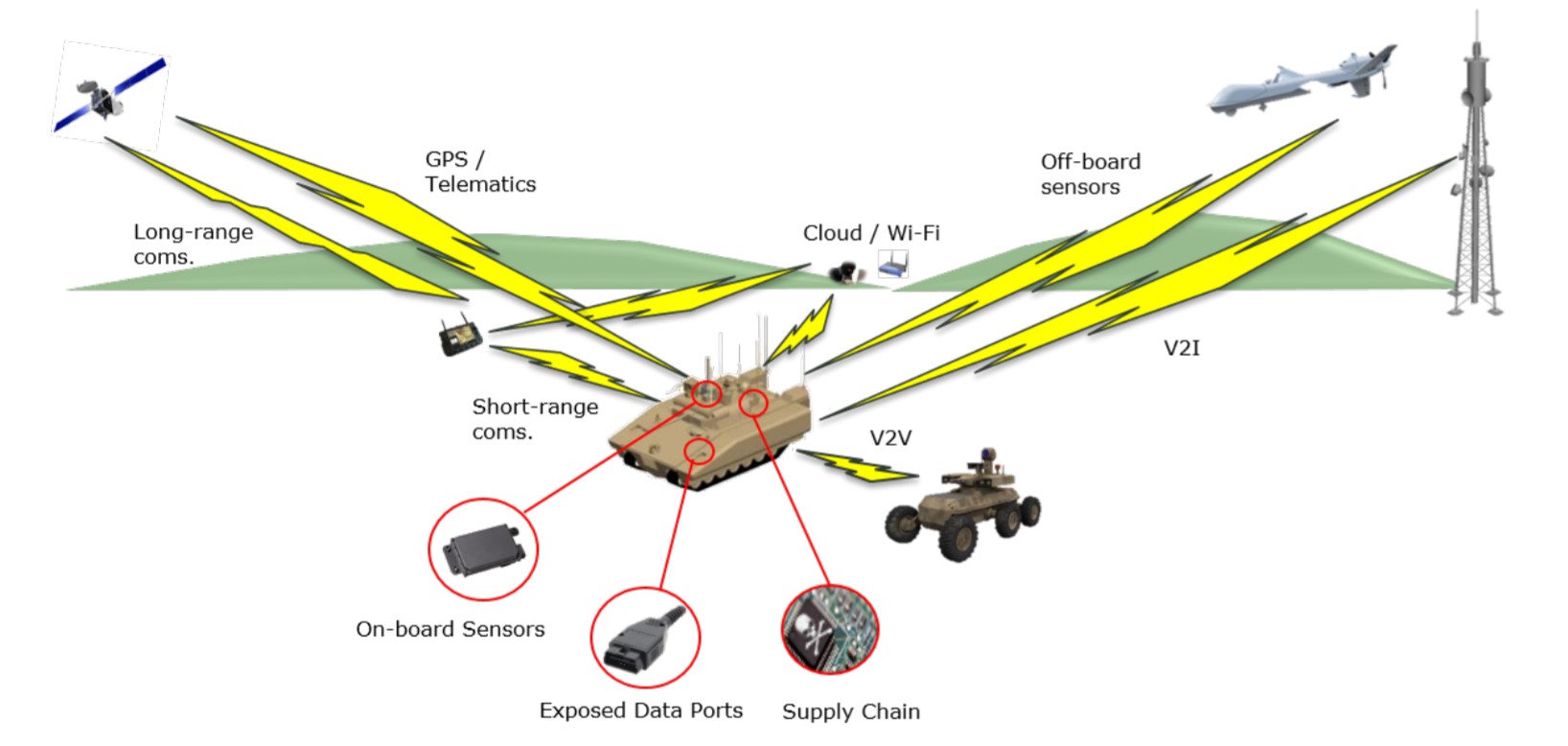

The demonstration was part of an exercise known as Cyber Cyclone, which took place at Yuma Proving Ground in September 2021 as part of the larger Project Convergence ‘21 event. The Army announced the demonstration this week in a release. In the demonstration, an M1A2 Abrams tank was fitted with a 1553 Bus Defender system made by Peraton. The Bus Defender is an intrusion detection and prevention system that can defeat cyberattacks aimed at a platform’s data bus, a hardware subsystem that handles the transfer of data both in and out of associated systems. All transmissions between other military assets including satellites, off-board sensors, communication systems, weapons, unmanned vehicles, and more are handled by the data bus. The Department of Defense and NASA use the MIL-STD-1553 data bus, first developed in 1975.

“Plain and simple: vehicles are susceptible to cyberattack,” said Jeffery Jaczkowski, associate director for GVSC’s ground systems cyber engineering, in a video released along with the announcement. “If you think about it, a vehicle today is just a bunch of computers on wheels or tracks. In recent news, there are countless instances of cyberattacks where either data or identity are stolen and similarly, attacks can occur on a vehicle.”

To test the Bus Defender, GVSC personnel executed “remotely triggered simulated cyber threats” aimed at the M1A2’s data bus. The exact nature of these attacks was not disclosed. When the Bus Defender was activated, it “successfully defended against the threats while maintaining full functionality and availability of the system,” according to the Army’s release. The system had been tested “several times in a military platform” prior to this demonstration, but the Army’s Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV) Cross Functional Team (CFT) wanted to conduct further assessments in “an operationally relevant environment.” The data from this most recent demonstration will inform further research with the system.

The Bus Defender was developed by GVSC’s Ground Systems Cyber Engineering (GSCE) Directorate under the project name “Vehicle Systems Security,” or VSS. The system is designed to ensure a vehicle’s critical systems cannot be tampered with or shut down by adversaries when operating in a near-peer cyber-contested environment.

Mustafa Hamood, Project Lead for Cyber Cyclone, said the goal of the project was to “demonstrate cyber resiliency and survivability by detecting, logging, mitigating, and defending against remotely triggered simulated cyber threats to a ground combat systems data bus from various distances, while simultaneously collecting data for forensic analysis.”

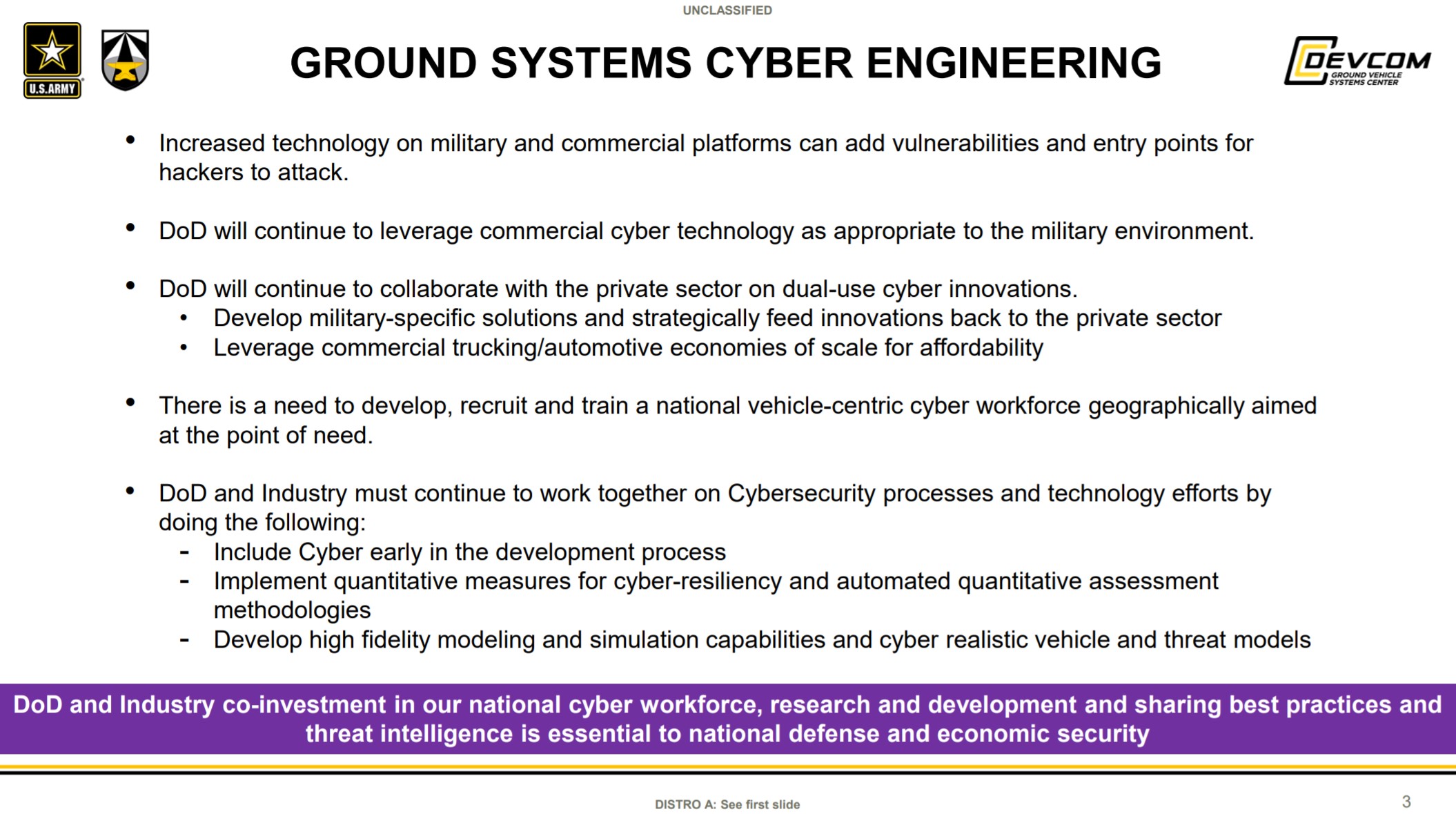

In 2019, GVSC signed a two-year cooperative research and development agreement, or CRADA, with General Motors to strengthen the Army’s automotive cybersecurity expertise. A similar CRADA was signed in 2020 with Washington, DC-based cybersecurity company Shift5. Those are unrelated to the recent Bus Defender demonstration, which was sponsored by the Defense Automotive Technologies Consortium and the U.S. Army Contracting Command – Detroit Arsenal.

The Army also hired Shift5 in 2020 to develop cybersecurity systems for the Army’s Stryker family of 8×8 wheeled armored vehicles. That came a year after it was revealed that unspecified “adversaries” had successfully launched cyberattacks on up-gunned XM1296 Stryker Dragoon, or Infantry Carrier Vehicle-Dragoon (ICV-D) variants, which The War Zone

was first to report. It remains unknown where and when the cyberattack or attacks occurred, who was behind them, what specific systems on the XM1296 were impacted, and to what degree.

The need to defend ground vehicles against cyberattacks, and more broadly all U.S. government and military networks, is becoming even more pressing as the looming crisis in Ukraine continues to worsen. When Russian forces first invaded Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region in 2014-2015, cyber warfare played a crucial role. In 2019, a Ukrainian officer explained how the country’s military’s Russian-made radios had suffered some kind of mass sabotage, apparently caused by what he described as a “virus” remotely trigging some kind of kill switch.

Russia has been known to demonstrate its cyber and electronic warfare capabilities during its own exercises, as well as those involving foreign troops. In 2017, it was reported that American forces and NATO allies stationed throughout the Baltic States and Poland were the targets of sophisticated cyber attacks in which troops’ personal cellphones and social media accounts were hacked. Russia has already been seen deploying electronic warfare systems to Ukraine over the last month that can locate and interfere with cellphone transmissions, and the U.S. federal government has already issued stern warnings that recent cyberattacks in and around Ukraine show the possibility for “widespread damage to critical infrastructure” in the United States.

Clearly, there is a need to protect networks both on and off the battlefield from the types of “hybrid warfare” that Russia is known to employ. Russia is far from the only nation that possesses such capabilities. Even non-state actors have growing cyber warfare capabilities at their disposal.

In the event of a future peer-state conflict, cyber warfare is sure to play a prominent role given the level of dependence on networked information systems and data sharing throughout the world’s militaries. It may very well be that systems like those demonstrated in the Army’s recent Cyber Cyclone become standard equipment throughout the service and are retrofitted to many of the service’s vehicles, even those based on a decades-old design, like the M1 Abrams.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com