There is a multitude of videos of military jets flying low and fast or employing ordnance. No doubt, they are exciting to watch. Even after a full career of flying U.S. Navy fighters, I still look up in the sky every time I hear a jet — the louder the better. But military jets are not designed to just go out and fly for show. They were built to accomplish a mission that ultimately involves employing ordnance to destroy a target. The footage seen in these videos is only a snippet of the life of an aviator. It does not represent the amount of preparation required for most flights. Time spent on the ground is not the glamourous part of the profession, but it is a vital part of what is required to be ready when called.

There are generally two types of training flights: part-task training and full mission flights. Part-task training is a flight when aircrew practices a specific skill multiple times on the same flight to focus on muscle memory and develop system familiarity. A common example is employing air-to-surface ordnance like a laser-guided bomb. Aircrew set up a racetrack pattern in a target area and execute multiple run-ins to practice checklists and proper switch movement required to properly drop the bomb, drilling the basics over and over.

Part-task training is a great way to dial in a specific skill, a ‘reps and sets’ mindset while minimizing the amount of planning required. But even a simple bombing flight would require aircrew to check for correct aircraft weapons loadout, valid (i.e. safe) employment parameters such as altitude and airspeed, check range manuals for proper weapons employment procedures, create a kneeboard card, etc.

The kneeboard card is a key piece of mission planning that is created for every flight. It is exactly what it sounds like, a folded-up piece of paper that goes on the aircrew’s knee for reference during the flight. It contains all the information needed during each flight: callsigns, communication frequencies, etc. For simple flights, the kneeboard may just be a folded-up handwritten piece of paper, also known as the ‘Farva Special.’ Most often though, it is a standard Microsoft Excel file that is edited for each event.

The kneeboard card should look the same for every flight so the aircrew knows exactly where to locate key information quickly. Do you remember the scene in Top Gun where Maverick and Iceman argue over the best macros to use for their standard kneeboard cards? Neither do I! Or I would have paid more attention to using Excel in kindergarten.

Full mission flights have many levels of complexity as well. To maximize resources, squadrons try to use every training flight to advance aircrew to their next qualification level. As a new aviator gains experience, they will qualify to lead a two-ship of aircraft (a section in Navy parlance), then a four-ship (division), and finally as a large force mission commander. The process for preparing, flying, and debriefing is roughly the same for every flight, even if it is not a qualification flight.

All missions begin with the mission objective. Examples could be to destroy a target or establish air superiority. The next step is to gather intelligence. What the target area looks like, what ordnance is needed for the target, threat systems, and expected responses. Using their intelligence findings, aircrew then develop mission planning factors they will use to accomplish the mission objective and counter or mitigate the threats.

Mission planning factors allow a flight lead to develop their brief for each event. Aviation depends heavily on standard operating procedures (SOP), and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). However, mission planning factors are never ‘standard.’ Thus, the goal of a good brief is to discuss what is different for that particular flight and then leverage off all the other standard procedures. The experience of the other aircrew also heavily dictates which portions of the event need to be covered in more detail to ensure everyone clearly understands every portion of the flight from takeoff to landing.

Two hours prior to takeoff is a pretty standard time to start the brief with the goal of around 45 minutes of actual briefing time. This time allows for a couple of minutes to grab a bite to eat and/or adjust gross weight (i.e. go to the bathroom) since we are not machines. After the personal program is complete, aircrew read the maintenance paperwork, get dressed out in flight gear, and preflight the aircraft so butts are in ejection seats 30 minutes prior to takeoff. I do not have personal experience, but apparently you need to add hours or even days to the preflight if you fly bigger aircraft.

Finally, the moment you have been training for! Slipping the surly bonds and going to fight the good fight. But in actuality, prior to getting on mission, there are other airborne tasks that must be accomplished first. These include administrative tasks such as joining up with your wingman, getting gas from a tanker, talking to air traffic control agencies or range control prior to the action. There is also tactical administration, or Tacadmin, which is getting your aircraft (turning on flight systems) and body (pulling Gs) ready to fight, as well as setting the training environment.

Additionally, there is usually a transit to get to the fight. And once the fight is done, all the Tacadmin (minus the G’s unless you have some gas to burn) and administrative tasks must be accomplished on the way back. For an hour and a half flight, the actual time of tactical flying is 20-30 minutes tops.

The debrief of the flight is always hard scheduled (keeps hyperactive O-5’s on track) for a time after landing, usually on average within two hours. Before that aircrew must complete post-flight paperwork including any maintenance issues with the aircraft and logging the flight time (that 3,000-hour patch is not going to sew itself!) Once complete, aircrew gather vital data required for the flight debrief primarily involving a review of flight tapes for validation of ordnance delivery.

Validation of weapons delivery was a major takeaway from the Ault Report, the same report that resulted in the creation of Topgun in 1969. In the review of hundreds of missiles fired during the Vietnam War, it was found, not only did aircrew often employ the weapons outside of an envelope that would allow for it to guide and fuze on a threat aircraft, but they were also unaware of what the proper envelope even was. The validation program has forced aircrew to become intimately familiar with these requirements to give their weapons the best chance of consummating an intercept or hitting a target. If a shot is not ‘valid,’ it does not count in the debrief. This is the equivalent of saying “bang I got you” when you were a kid and your friend replying “no you didn’t, you missed!”

Once the post-flight paperwork is complete, it is time for the debrief, by far, the most important part of any flight. If we do not go over our mistakes and learn from them, we have wasted all the time and effort everyone has put into launching multiple high-performance aircraft.

There are two acronyms aircrew use for the order of the debrief. The first is for basic flight data that gets everyone in the debrief on the same page. BATTSEA stands for brief, admin, Tacadmin, training rule violations, safety of flight, environmentals (i.e. weather), and alibis (i.e. aircraft systems that did not work). BATTSEA is a quick, big picture overview of the issues that affected the flight that will be covered in greater detail during the full debrief.

The second acronym is FATT (facts, analysis, tapes, teaching). This is the most efficient way to get the most out of the debrief without going off on too many tangents.

The facts portion of the debrief involves all members of the event, including the bandit or adversary lead. It is usually a fairly scripted event that prevents individuals from derailing the debrief by discussing non-pertinent information. In fact, the individual running the debrief needs to be a benevolent dictator; permit learning, but keep the trains running on time.

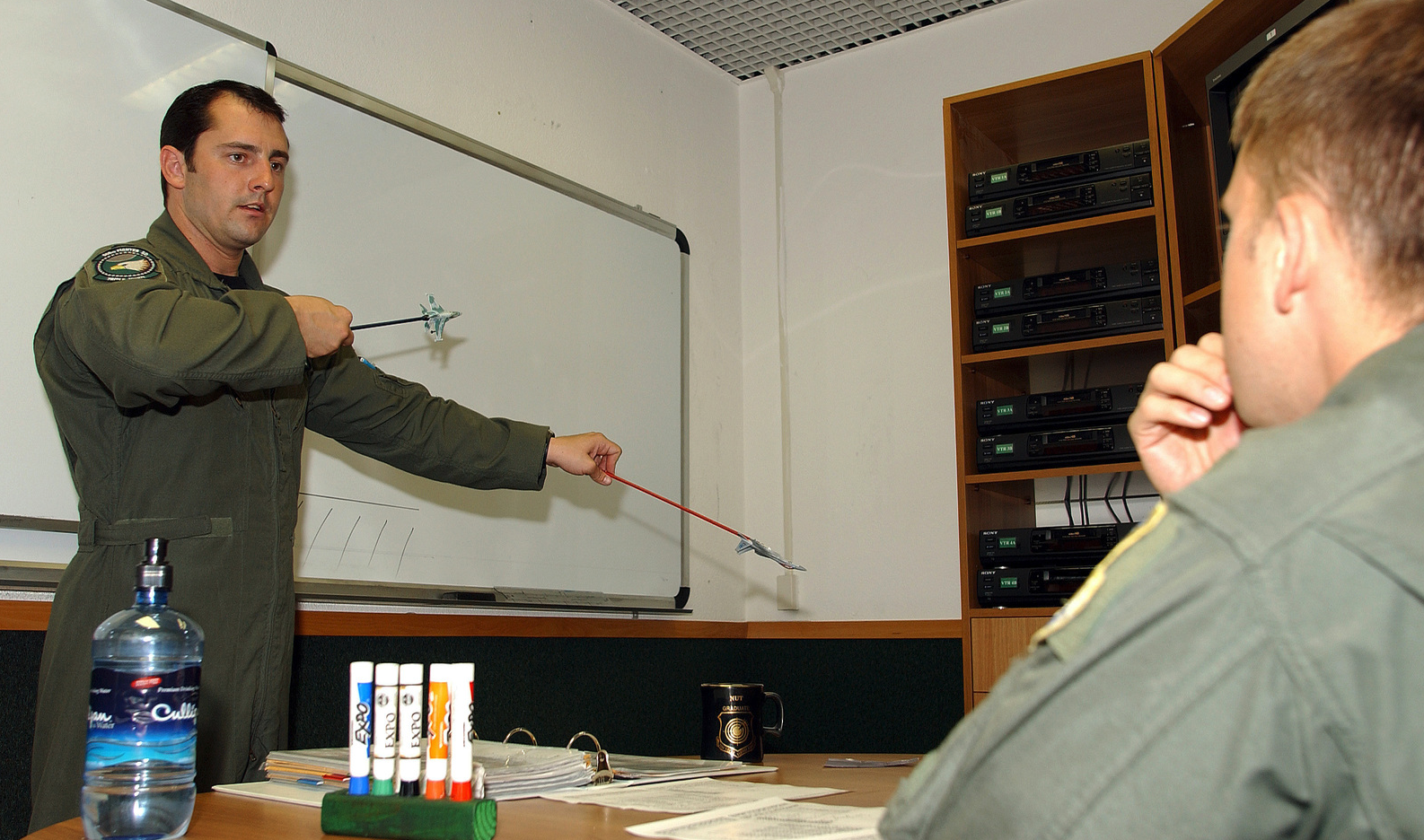

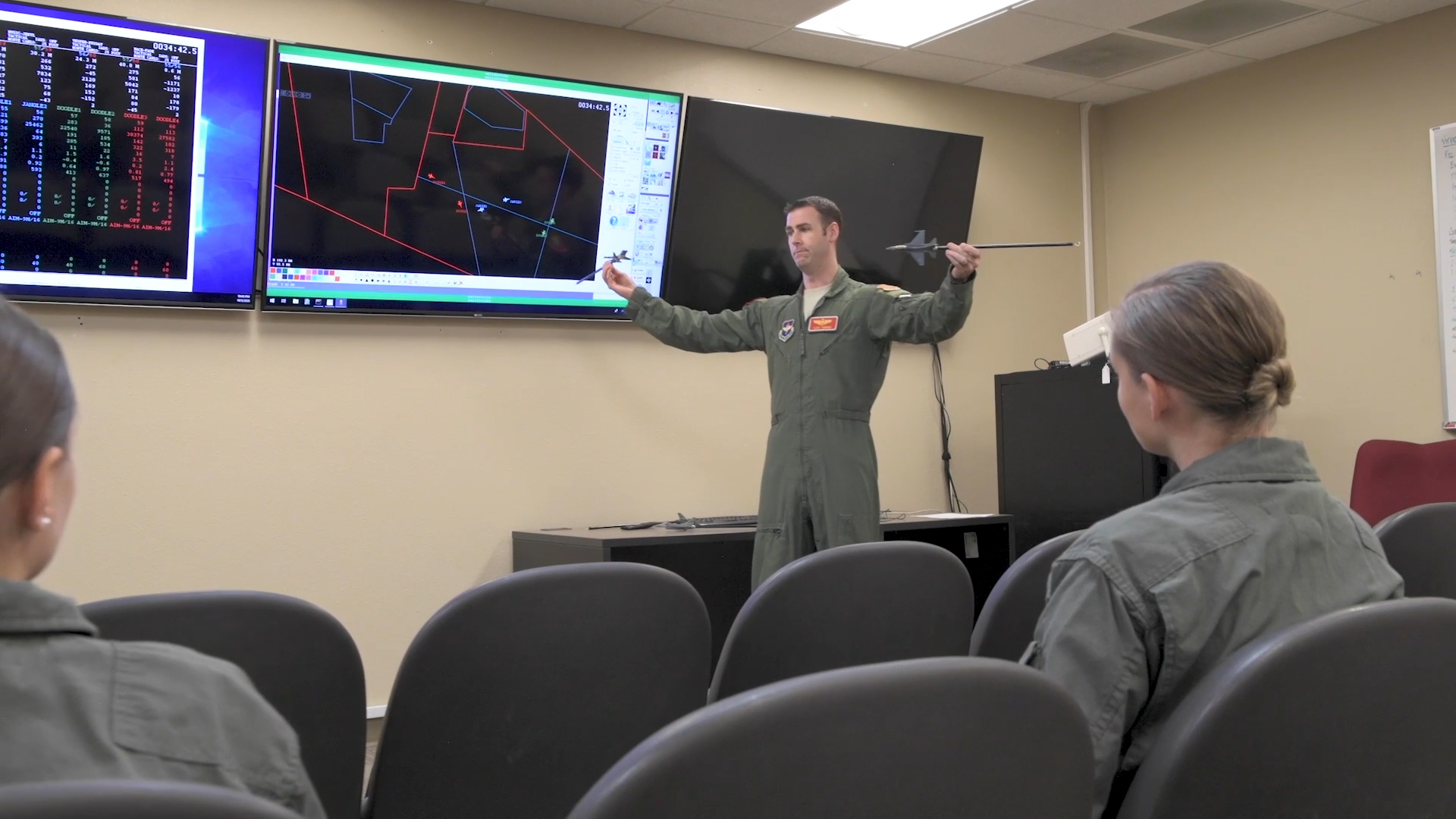

This part of the debrief can be done on a whiteboard by drawing chronological arrows of all aircraft positions during the flight. Or it can be done as a Tactical Combat Training System (TCTS) debrief, which is a digital replay of aircraft position played on a screen. TCTS is the preferred method, my first ever whiteboard debrief that I ran resulted in dry erase marker all over my face and three Topgun instructors shaking their heads in disappointment. True story.

The primary goal of the facts portion of a debrief is to ensure the aircrew’s memory matches the reality of what actually happened and to identify learning points. So it serves two purposes. First, flight recall is an important skill for aircrew to develop because it allows them to recognize mistakes in real-time in flight. Also, in larger flights, aircrew also may just not be aware of what actually occurred in a different part of the battlespace. Aircrew each note learning points or timestamps during the fight that warrant a more focused look later in the debrief. The facts part of the debrief is the chance to clear up any and all confusion that occurred during the flight, including who was killed and who survived.

After the first run-through of the event, a communication review is conducted of the flight by listening to the communications in real-time by all aircrew. Again, this clears up any confusion that occurred during the flight because communication calls that were incorrect or missed due to aircrew being too focused on another task. The communication review is also an opportunity for aircrew to correct the improper use of an Air, Land, and Sea Application (ALSA) brevity term or other incorrect calls.

Once the facts have been hammered out, it is time to move into the analysis portion for the debrief. This is the time to talk and discuss every single good and other (nicer way of saying bad) thing that occurred. Flight lead decision-making is a big part of the analysis. Oftentimes, a failed mission objective can be traced back to a decision made minutes earlier by the lead. This portion of the flight is usually a more free-flowing back and forth discussion.

The analysis of the flight continues in the tape debrief. The tapes for each aircraft are reviewed by the aircrew looking at systems such as the radar or forward-looking infrared (FLIR) displays that were recorded during the flight. Aircrew check to ensure the systems were set up in accordance with the brief and standard operating procedures. They also review their mechanics of how they manipulated each system to ensure they performed in accordance with procedures and if they missed or misinterpreted any data presented to them.

During the tape review, all shots and employment of ordnance are validated again in a methodical manner. This again reinforces and builds the scan aircrew use for their displays so they are able to recognize a valid (or more importantly, invalid) shot envelope as quickly as possible.

Finally, it is time for the teaching. A good debrief involves no rank. A junior officer will teach a commanding officer and vice versa. Nobody has a perfect flight, and all aircrew need to leave ego at the door and accept feedback to improve their skills and knowledge for the next flight. This is the part of a debrief where tactics, techniques, and procedures are discussed and reviewed. Tactics can change quickly and we want to ensure all aircrew are familiar and up to date on the most current way to employ their aircraft.

Actually, we are not probably finished yet. If there is an aircrew who is under instruction leading the flight, the actual instructor, who is usually a wingman, will debrief the debrief, and the brief, and the flight. Almost every flight follows the same general flow of the debrief with slight variations between different missions.

So as mentioned, the event length of a flight from start to finish can vary greatly with the complexity of the flight, and as aircrew get more experienced, they will get more efficient at the process.

Here are a couple of examples of average times for training events:

A basic fighter maneuvers (BFM, aka dogfighting) part-task training flight will take one hour of planning, one hour for the brief, one hour to walk/start/taxi, half an hour for post-flight paperwork, one-hour drawing arrows on the whiteboard, one-hour validating shots, one hour for the rest of the tape debrief, all for a half-hour of total flight time. It’s an eight-hour day for a half-hour flight.

The Strike Fighter Advanced Readiness Program (SFARP), is a blocking and tackling training detachment for Navy F/A-18’s focusing primarily on 4-ship (Division) tactics. An SFARP event would take about five hours of mission planning, an hour and a half for the brief, one hour to walk/start/taxi, half an hour for post-flight paperwork, half an hour for shot validation, hour and a half for TCTS debrief/communication review/analysis, and an hour and a half for tape review/teaching. SFARP flights are airborne for an hour and 15 minutes, of which 25 minutes is the actual fight time. A 12-hour day for just over an hour of flight time.

Air Wing Fallon is a five-week detachment where the Navy trains large force mission commanders. The student mission commanders are given six hours and an entire team of aviators to accomplish their mission planning. More often than not, the mission planning team needed the entire time to prepare for the flight.

So, an Air Wing Fallon mission is six hours of mission planning (which doesn’t include the planning done on previous days), two-hour brief, one hour to walk/start/taxi, half an hour for post-flight paperwork, half an hour for shot validation, hour and a half for TCTS debrief/communication review/analysis. Air Wing Fallon flights are airborne for around an hour, of which 25-30 minutes is the event. Just like SFARP, it’s a 12-hour day for around an hour of flying.

If it sounds like a lot, well it is. Briefing and debriefing flights can be quite overwhelming for new aviators. But it just takes practice and repetition and eventually, everyone finds a rhythm and process that works for them.

Military aviation is a profession, which means it requires continual training. We, as military aviators, owe it to the troops on the ground, our Sailors that maintain the aircraft, and of course, the taxpayers, to ensure we are the most capable aircrew in the world. Time in the air is essential, but the time on the ground is equally important.

The ability to brief and debrief is just as vital as stick and rudder skills. The stick and rudder sells videos, but the brief and debrief accomplishes the mission.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com