Lockheed Martin will convert Airbus A330s into LMXT aerial refueling tankers inside a facility that it previously used to do modernization work on C-5 Galaxy transport planes if it wins a forthcoming U.S. Air Force contract. The company revealed this and other aspects of its proposed plans for actually assembling and converting LMXTs, as well as additional details about the aircraft’s U.S.-specific configuration, earlier today.

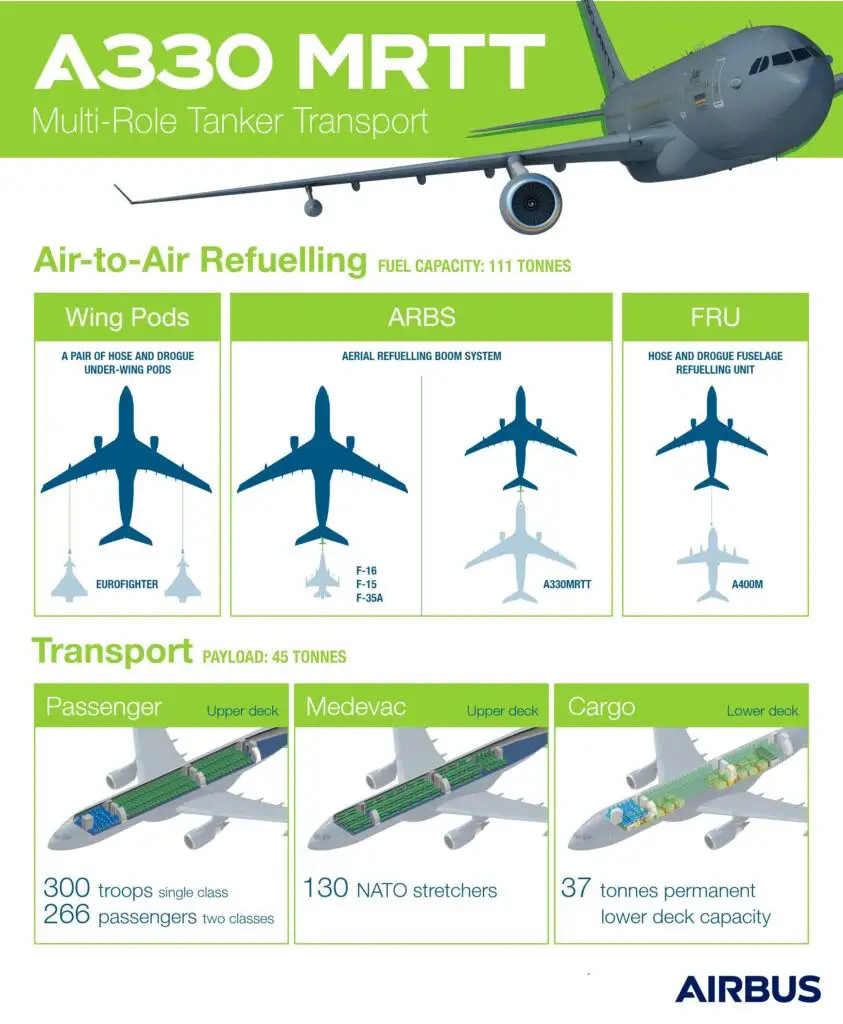

Larry Gallogly, the Director of the LMXT Program at Lockheed Martin, laid out the company’s current plans for the LMXT for The War Zone and reporters from other outlets during a call this morning. The company formally announced last September that it would submit this aircraft, a U.S.-specific derivative of the Airbus A330 Multi Role Tanker Transport, or MRTT, in response to the U.S. Air Force’s requirement for additional tankers to “bridge the gap” between the end of its planned purchases of Boeing KC-46A Pegasuses and the acquisition of a still largely undefined advance future aerial refueling aircraft. This interim tanker program is commonly referred to as both the Bridge Tanker and KC-Y.

The Air Force presently plans to purchase 179 KC-46As across 13 production lots, with the last of those aircraft being delivered in 2029. The service wants to immediately begin receiving KC-Ys after that, and it expects to buy between 140 and 160 examples of whatever design it chooses. The existing fleet of KC-46As and these new aerial refueling aircraft are expected to eventually replace at least the vast majority of the Air Force’s existing KC-135 and KC-10 tankers.

“This is going to be built in America by Americans for Americans,” Gallogy said of the LMXT. “We’re trying to source as much of the supply chain in the United States as we possibly can.”

As key parts of that plan, Lockheed Martin’s proposed LMXTs will start life as A330 aircraft assembled at Airbus’ plant in Mobile, Alabama. Those planes will then head to Lockheed Martin’s facility in Marietta, Georgia for conversion into tankers. Gallogy said that it would take between three and four years to produce each one of these planes, with it taking around two years to produce a ‘green’ A330 and another 18 to 24 months to convert it into an LMXT. That timeline could shrink as production increases.

At present, Airbus primarily assembles certain models of the A320 airliner in Mobile, but the company already plans to transition work related to older models of the A330 to that site in the future separate from the Bridge Tanker deal. Lockheed Martin’s Marietta plant is currently home to the final production line for the C-130J Hercules cargo plane and assembly line that makes center wing assemblies for all three F-35 Joint Strike Fighter variants.

Interestingly, the Airbus plant in Mobile had originally been proposed as a site to assemble A330s and convert them to MRTTs for the U.S. Air Force as part of an earlier partnership between that company and Northrop Grumman. Northrop Grumman and Airbus’ proposed Americanized MRTT variant, known as the KC-45A, lost out to Boeing’s 767-based KC-46A in 2011. That competition had followed the Air Force’s awarding and subsequent canceling of a contract with Northrop Grumman and what was then known as EADS for an earlier version of the A330-based tanker in 2008. You can read more about that entire saga here.

Currently, Airbus transforms A330s built in France into MRTTs at a facility in Spain. Though the specifics are still being finalized, the Mobile assembly line will need to be expanded to accommodate the increase in workload to meet the bridge tanker requirements, while the L10 building at Marietta will need to be reconfigured to support the LMXT conversions.

Lockheed Martin did choose the L10 building specifically because it offers an immense amount of physical space to begin, having been the site of the recently concluded C-5 modernization effort for the U.S. Air Force. This structure is big enough to accommodate four Galaxy transport planes at once, providing more than enough room to establish a tanker conversion line.

Gallogly said that Lockheed Martin estimates that the company would add 1,300 new jobs to its existing workforce to support the LMXT program, not including those that might be created elsewhere in the supply chain, if the company wins the KC-Y contract and these plans come to fruition. He also highlighted the company’s existing economic impact across Alabama and Georgia, which is valued at $8.3 billion.

At the same time, the LMXT program would proceed “recognizing and respecting that there’s a very successful existing supply chain that supports the MRTT right now,” Gallogly added. “We don’t want to do anything that is going to increase the overall cost of the aircraft or induce any risk into our producing and performing with this aircraft.”

Gallogy pointed out that this is all made easier in no small part because of the existing Airbus assembly line in Mobile and that A330s are already being made with a significant number of U.S.-sourced components. He further noted that while Lockheed Martin has not settled on what engine might power the LMXT, the two options that are under consideration, one from Rolls-Royce and another from General Electric, are both made in the United States.

“This aircraft has to work on day one,” he stressed. “So, we’re very cognizant of keeping the risk to a minimum.”

Altogether, Lockheed Martin is clearly looking to avoid any unnecessary changes to the core MRTT design or its components, while at the same time looking for all possible ways to maximize the use of American-made components. In addition, the company only plans to establish the facilities in the United States to support the LMXT program if its receives the Bridge Tanker contract. As such, at least some number of prototype aircraft will initially come from Airbus’ European production and conversion lines. Airbus will also help train Lockheed Martin’s U.S. workforce on key aspects of the MRTT conversion process and will support engineering work on the initial LMXT design, as well as any future upgrades or other modifications.

It is important to remember that this is all contingent on a contract award from the U.S. Air Force. Boeing plans to pitch the KC-46A again for the Bridge Tanker contract. While it remains to be seen if any other companies attempt to enter the fray, it is most likely that the KC-Y competition will be the third head-to-head fight between the KC-46A and a variant of the MRTT in the last 15 years or so.

At the same time, Lockheed Martin is positioning the LMXT as having both distinct advantages over the KC-46A and existing MRTT variants. The LMXT configuration heavily emphasizes fuel capacity, something that Lockheed Martin says it expects to be a key factor in what design the Air Force picks for the Bridge Tanker deal, even though the service has not yet finalized its requirements.

“Regardless of whether we’re talking to Air Mobility Command, or Transportation Command, or the acquisition folks at the Pentagon, or theater commanders, the number one priority has always been fuel offload at range,” Lockheed Martin’s Gallogy explained. “That’s the gap that needs to be filled, and obviously, as you’re all aware with all the focus on China and the tyranny of distance that exists in that theater, we’ve got a lot of fuel that has to be moved. So, that is the number one priority and that is what we have based our proposed configuration on.”

As it stands now, the LMXT has two additional fuel tanks in the lower fuselage that can together hold around 13 tons of fuel. This gives the LMXT a total fuel capacity of 135 tons, both for its own use and for offloading into receiver aircraft, as well an unrefueled range of 10,000 nautical miles. This means the aircraft can carry more gas than a typical MRTT and fly further without needing to top up its own tanks, but at the cost of cargo space. Lockheed Martin says the planes will still have a useful capacity to move cargo, as well as personnel, and be permanently fitted with an aeromedical evacuation suite. Airlift and aeromedical evacuation are important, if often overlooked secondary mission sets for U.S. Air Force tankers.

Gallogy also highlighted the maturity of the underlying MRTT design, particularly the refueling boom that Airbus has designed for it and the remote vision system that boom operators in the main cabin use to guide it into receiving aircraft. The entire system as it exists now is highly automated, as you can see in the video below.

The boom and vision system on Boeing’s KC-46A have been among the most serious of a number of persistent problems that have plagued the aircraft over the years. The Air Force and Boeing are still years from resolving these issues, which have significantly limited the utility of those aircraft. There are now concerns that the plans for how to fix the Pegasus’ boom and remote vision system could risk causing new problems and subsequent delays in getting the aircraft to a fully operational state, as you can read more about here.

This all could have an impact on how many of these planes the Air Force buys in the end, as well as increase the service’s interest in an alternative design of the Bridge Tanker program. Boeing is only on contract, so far, to deliver 91 of the expected 179 KC-46As. It just recently delivered the 55th example to the Air Force.

“I was asked by an extremely senior U.S. Air Force official that will remain unnamed what we were going to change on the aircraft and we went through those changes,” Gallogy said, underscoring the service’s obvious desire to avoid the issues that the KC-46A is experiencing when it comes to the future KC-Y. “He specifically said ‘are you going to change the boom?’ And I said ‘no, we have no plans to change the boom or vision system.’ He said, ‘good, don’t mess up the boom.'”

The LMXT will also feature a variety of other systems, including communications and other networking capabilities, as well as self-protection features, that will differ from other MRTTs in order to meet U.S. Air Force-specific requirements. Gallogy highlighted how the aircraft’s configuration will provide significant space to support communications and data-sharing mission sets, and even potentially a limited battle management role. The Air Force has already been exploring the possibility of using tankers as a component of its future networking plans as part of the service’s Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) initiative and the Pentagon-wide Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) effort.

“Beyond the fuel, the aircraft has to be a node in the system and we are planning a full JADC2 suite, Gallogy said. “When we talk to them [the Air Force], their description of a node is not just a relay station, it’s not just hanging a pod on the wing … it’s a far more robust communications node, because these aircraft are going to be persistent in that combat environment. The tankers are going to be out there all of the time.”

Exactly what the final LMXT configuration might look like remains to be seen. Lockheed Martin expects the Air Force to have its Bridge Tanker requirements finalized by next year, with the possibility of a contract award in 2024.

There is a question about whether the LMXT might still become a reality even if Lockheed Martin loses its bid to supply tankers as part of this acquisition program. Right now, the company insists that this aircraft would be exclusively for the U.S. government market, but that leaves open the possibility of selling or leasing planes to the Air Force or some other branch of the U.S. military. U.S. Transportation Command, in cooperation with the Air Force, has been looking into how private contractors, flying their own planes or government-owned aircraft, could provide additional aerial refueling capacity for non-combat missions, such as training and test and evaluation work. The U.S. Navy already uses contractors for this purpose. Back in 2018, Lockheed Martin had itself announced an aerial refueling-related partnership with Airbus that included discussions about offering contractor-owned and operated MRTTs.

It is equally unclear if Lockheed Martin, in cooperation with Airbus, might eventually be willing or able to try to market the LMXT or a derivative thereof for export. A version of the MRTT that U.S. allies and partners can purchase through American military assistance mechanisms, such as the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program, could potentially be a very attractive offering. Right now, MRTT variants are in service with 14 different operators, including a multi-national fleet under the control of the NATO alliance, giving it a well-established user base.

No matter what, Lockheed Martin’s plans to assemble and convert LMXTs in the United States, and focus on establishing U.S.-based supply chains, underscore how fierce the competition will be for the Air Force’s Bridge Tanker deal.

Update 2/1/2022:

After yesterday’s press call regarding the LMXT, The War Zone reached out to Lockheed Martin for more information about the potential to offer the aircraft to the U.S. government on a contractor-operated basis or for export through programs like FMS. A spokesperson for the company has now provided the following responses to those questions:

The LMXT is only offered to the U.S. Air Force. The MRTT will remain a global option and managed by Airbus. Any potential interest in the LMXT through the FMS process would be managed jointly by Lockheed Martin and Airbus.

Lockheed Martin is not currently considering a commercial air refueling operation. However, we will evaluate all opportunities once the Air Force determines the size and scope of such operations.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com