The War Zone recently reported updates on our ongoing investigation into a strange series of incidents in the summer of 2019 that involved swarms of unidentified aircraft shadowing U.S. Navy vessels in the waters off Southern California. In our last update, we reviewed new documents released to us via the Freedom of Information Act. These documents show that the mysterious incursions continued throughout the month of July, far longer than originally understood. Amid the ongoing swarm activities, the Navy appears to have implemented and conducted exercises using a variety of counter-drone measures. These exercises included the use of a 5-inch naval gun in a live-fire drill, as well as apparently deploying a new “ghostbuster” team that we suspected was utilizing portable counter-unmanned aerial system (CUAS) electronic warfare devices. A newly found reference buried in the documents cements this suspicion.

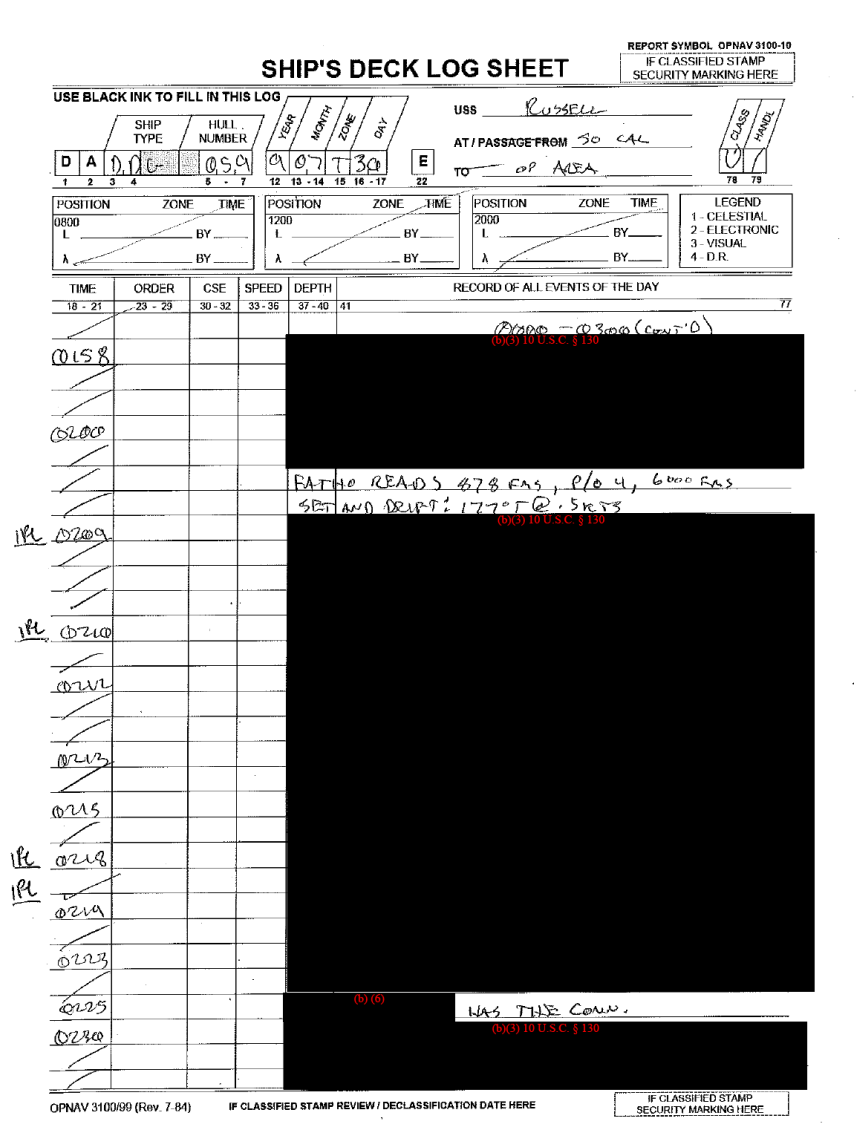

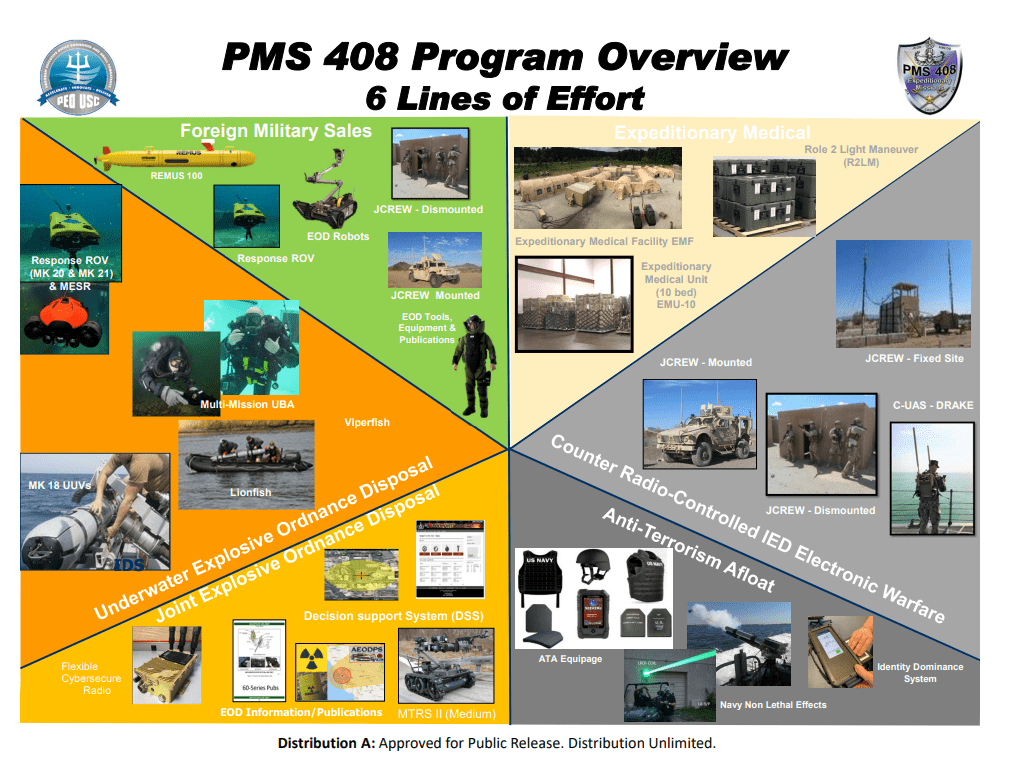

After further review of the logs released to us, we have found a reference to Northrop Grumman’s Drone Restricted Access Using Known EW (DRAKE) system. This backpack system, pictured above, has now become one of the Navy’s frontline tools for deterring drone threats. The reference to DRAKE is scrawled in a deck log entry from the USS Russell that came shortly after one of the more significant incidents.

Navy records show that multiple unidentified aircraft were spotted by several ships in the early hours of July 30, 2019, approximately two weeks after the initial swarming events. Uncharacteristically for the records we’ve reviewed, the logs of the Russell are nearly completely redacted in connection with this particular incident.

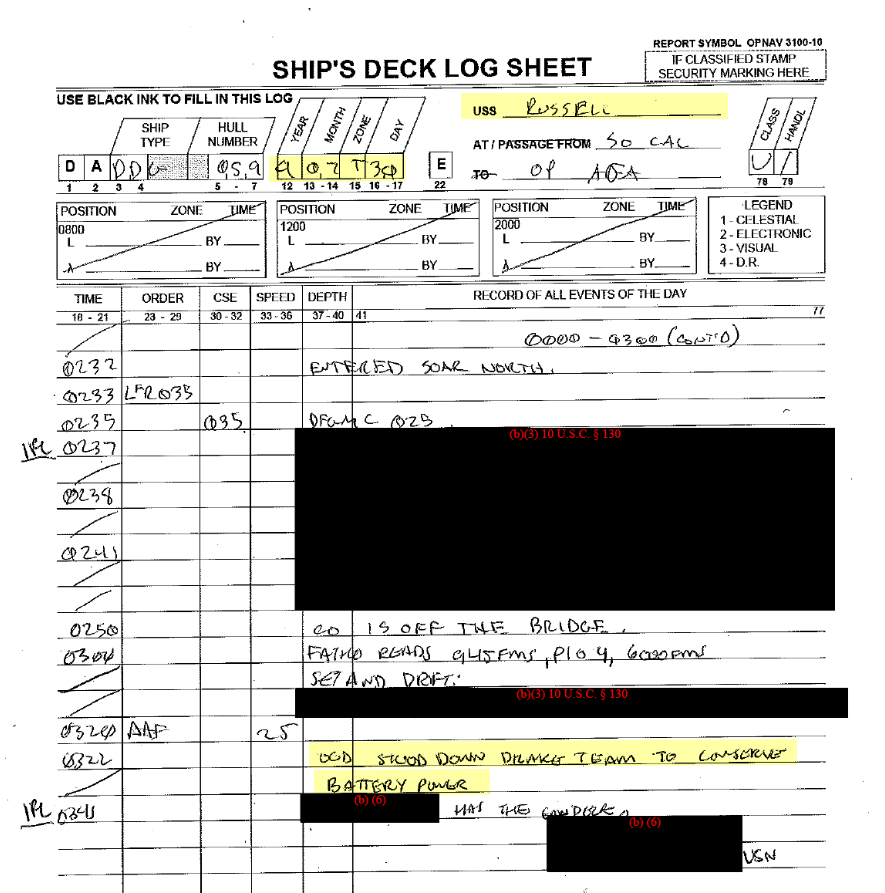

As we previously reported, the logs reference a call for the “ghostbuster” team near the apparent start of the event around midnight. Just after the lengthy redactions, this 3 AM entry states “stand down DRAKE team to conserve battery power.” It is unclear if the ghostbuster team is distinct from the DRAKE team, but the term “ghostbuster” is an established slang term for man-portable counter-unmanned air system electronic warfare devices, which commonly look like the devices used in the 1980s hit film. In any event, the reference to DRAKE makes it clear that portable CUAS systems were deployed during the incidents that occurred at the end of July.

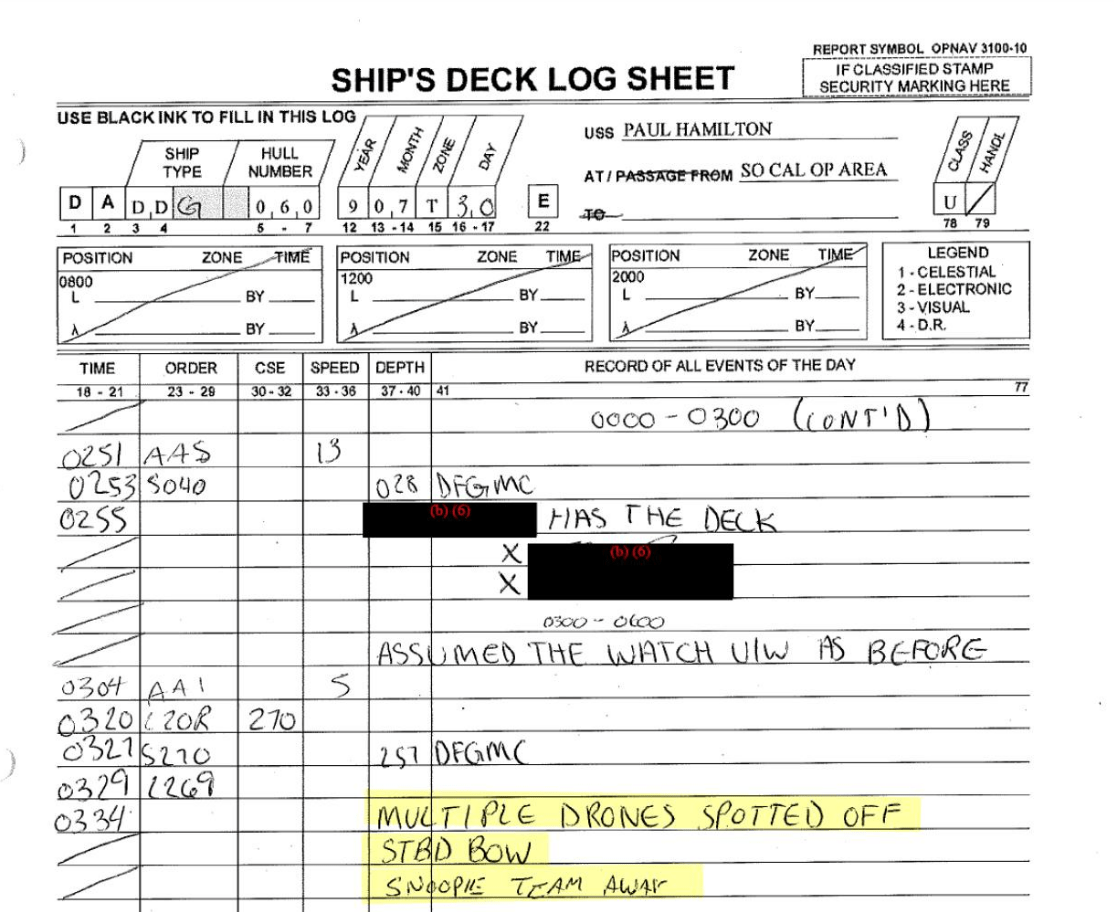

The DRAKE system appears to have been used in the same timeframe as drones were being reported. Just minutes after the system was shut down to conserve power, the USS Paul Hamilton separately reported “multiple drones spotted off stbd [starboard] bow.” The next line contains a further reference to the Ship Nautical Or Otherwise Photographic Interpretation and Exploitation (SNOOPIE) team. These are teams of sailors trained to enhance situational awareness and document unknown contacts or events of interest.

Other ships reporting drone sightings do not appear to have mentioned use of the DRAKE or “ghostbuster” teams. It still is not totally clear if this equipment was already on board, or if countermeasure devices were introduced in reaction to the ongoing incidents. To date, it appears that the Russell’s logs contain the only references to electronic warfare drone countermeasures. To our knowledge, portable CUAS devices were not widely deployed to ships operating in home waters in 2019. Their sudden appearance in logs just weeks after a significant incident indicates that they may have been deployed as a response to the ongoing events. They also only surfaced after a major counter-UAS training exercise, which seemed well-timed considering the continued incursions throughout the second half of July. While the Navy has increasingly adopted these kinds of devices to respond to drone threats, in 2019 many of them were still in developmental testing.

Prior to its use in the Navy, DRAKE was initially a Humvee-mounted jammer system used during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In a 2016 announcement to investors, Northrop Grumman described DRAKE as a “radio-frequency negation system that delivers a non-kinetic, selective electronic attack of Group 1 drones.”

The reference to “Group 1” drones is a significant aspect of the design of DRAKE. The Department of Defense has categorized drones into five groups, based on their size and typical operating altitude. Group 1 drones are described as “typically hand-launched, self-contained, portable systems employed for a small unit or base security.” These drones are under 20 pounds and fly at less than 100 knots. In essence, Group 1 drones refer to the smallest and typically least sophisticated drone threats. You can watch an earlier version of DRAKE disabling a small drone here:

In terms of its modern naval context, DRAKE continues to be a tool oriented to low-end threats. Speaking to USNI News late last year, Gunner’s Mate Kyle Mendenhall explained that “anybody these days can kind of just buy a $1500 drone. … The Navy saw a very big need for having something to defend ourselves against something so simple that is so common these days.”

The DRAKE device essentially acts as a jamming system that interferes with frequencies commonly used by low-end drones. The relatively simple system can be used as a basic countermeasure, particularly in situations that require a quick reaction. Mendenhall explained to USNI News: “If we encounter a [drone] that happens to come up on the forward-end of the ship, up near the foc’sle, and then it just decides to bolt and go to the aft end on the flight deck, I can just pick this backpack up, I can run to the flight deck and I still keep blocking that signal to make sure the drone stays away from us.”

Mendenhall further explained that the system requires authorization from the ship’s commanding officer to use, but it can also be used in reaction to a threat, telling reporters, “If it’s something that we deem a threat, I can turn it on no big deal, and I will backfill basically the chain of command.”

DRAKE’s simplicity also likely limits its utility against more sophisticated threats. Drones employing autonomous guidance systems or that are otherwise hardened against jamming attacks are unlikely to be successfully countered by something like DRAKE. However, because the device uses specific radio frequencies that Group 1 drones typically employ, it is also less likely to cause unintended interference with the ship’s own systems. In short, DRAKE is specifically designed to stop a low-end drone that is operated manually via continuous RF control.

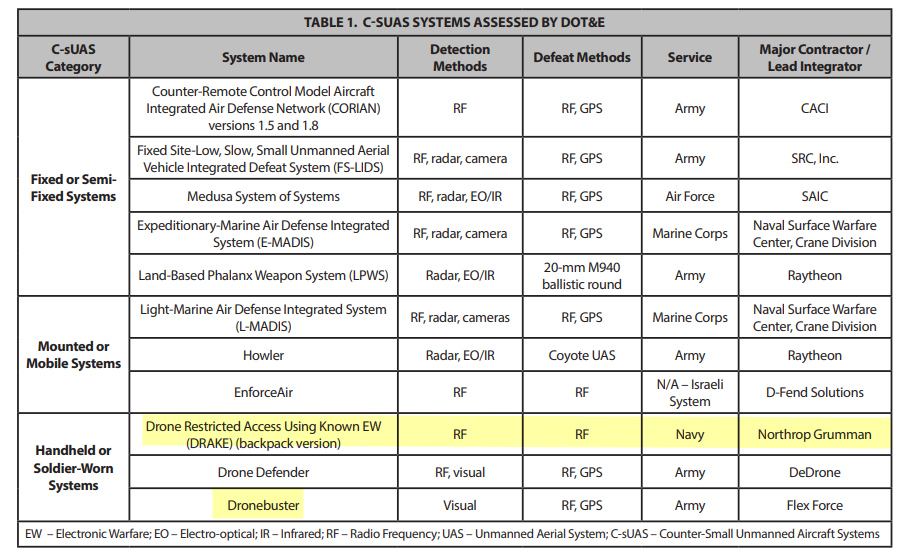

The efficacy of the Department of Defense’s CUAS platforms against more sophisticated threats has been a pressing and open question for some time. In July 2019, the same month as the initial swarming incident, the Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment requested an evaluation of the performance of 28 counter-drone systems in use across the military. DRAKE was among those tested.

Following this request, the service branches and the Operational Test & Evaluation Office of the Secretary of Defense conducted extensive assessments of countermeasures. These tests focused exclusively on low-end Group 1 drone threats. Their joint findings emphasized that while detection capabilities are adequate for most systems, actually defeating the drones remains challenging.

These findings came with a number of significant caveats. Group 2 drones were not available in time for testing in 2020, and more sophisticated drones were considered beyond the scope of testing. The assessment notes that swarm threats were simply not considered at all. These gaps in the testing were explicitly identified in the findings, with further recommendations to address more sophisticated drones and swarm tactics in the future.

Since the request for this evaluation occurred at approximately the same time as the swarm events, it appears the Department of Defense could not have had a rigorous assessment of the efficacy of its various counter-drone technologies. Perhaps more concerning, the review noted that disabling even the more limited Group 1 devices was a challenge across a wide number of systems.

Based on their endurance and the use of multiple aircraft, it is improbable that the aircraft involved in the 2019 incident would be characterized as low-end Group 1 drones. Given that the deck log reference to shutting down the DRAKE system appears at the end of a lengthy and entirely retracted section of the logs, it is impossible to know what specific role or impact DRAKE played in these events. Those redactions may well be in place to protect the performance of the countermeasures employed, specifically DRAKE. It also bears repeating that it is not yet clear if DRAKE was used by “ghostbuster teams” or if there were separate systems in play. As we noted earlier, the “ghostbuster” nickname is common among a number of portable CUAS devices because they often utilize large backpacks reminiscent of the Ghostbuster films. Indeed, photos of DRAKE do show a large backpack with very prominent antennas.

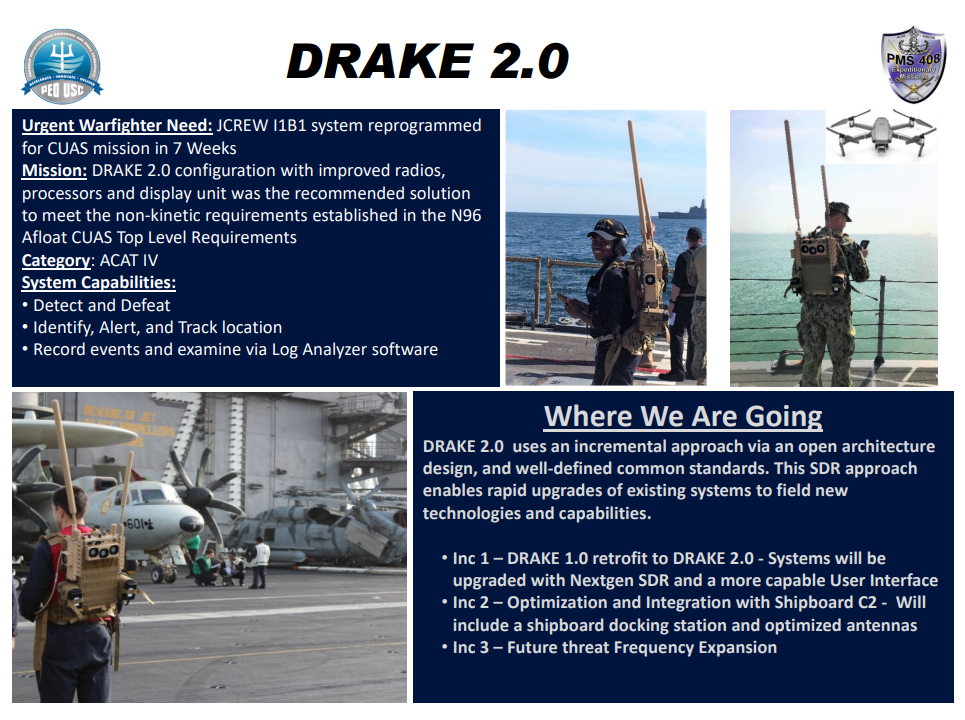

Whatever its role in the 2019 incident, DRAKE is an ongoing program. A recent Navy presentation listed DRAKE among counter radio-controlled IED electronic warfare efforts.

Slides detail a new “DRAKE 2.0” which will incorporate improved radios and software systems. These upgrades will include a docking station that will allow the system to better integrate with the ship.

As it stands, this subtle clue in the deck logs shows that the Navy did deploy portable CUAS systems in connection with these incidents. While we have reached out to Navy public affairs officials for further information, it is the Department of Defense’s policy to not comment on incidents like these. For the time being, Freedom of Information Act documents remain an essential if limited window into these events.

We will update readers as we learn more.

Contact the authors: Adam@thewarzone.com and Marc@thewarzone.com