Richard Crandall started his Air Force flying career in the F-111 Aardvark, but found himself in the cockpit of the mighty F-15E Strike Eagle, the service’s newest jet, during Operation Desert Storm. Although F-15C/D Eagles were already a staple in the Royal Saudi Air Force by the time Desert Storm kicked off, the Strike Eagle would eventually find its way into the Kingdom’s aerial arsenal in the form of the F-15S. Today, Saudi Arabia flies around 70 of these jets, and soon they will receive 84 F-15SAs, the most advanced Strike Eagle derivative ever produced.

Now Crandall serves as a contractor with the Royal Saudi Air Force, where he puts his experiences flying and fighting in the F-15E “Mud Hen” to use. Below, read Crandall’s perspective detailing how the Strike Eagle first arrived in Saudi Arabia, how they were baptized by fire during Desert Storm, and how they differed from the Strike Eagles flown today.

Strike Eagles arrive in the Kingdom

Saudi Arabia has flown the F-15 Eagle for a very long time. The Kingdom bought the Eagle and started flying them long before Desert Storm in 1991. Royal Saudi Air Force pilots flying the F-15Cs even shot down two Iraqi fighters during the war.

Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990. In that same month, the USAF’s newest and most potent strike fighter, F-15E Strike Eagle, landed in Saudi Arabia for the first time, but its stay was brief. The jets were only on the ground for a few hours at King Abdulaziz Air Base in Dharan. They were refueled and immediately departed for Thumrait, Oman.

At the time, their presence in the Kingdom was considered too offensive, and some worried it might result in Iraq immediately crossing the border into Saudi Arabia. The only way to stop them was deploying the Saudi Army and the 82nd Airborne. The 82nd Airborne would have fought valiantly, but its anti-armor capability wasn’t there, and it would have been a speed bump under Saddam Hussein’s armored forces.

For the next six months, the USAF’s first operational F-15E unit, the 336th Fighter Squadron “Rocketeers,” flew from Oman, while the great military buildup leading up to Desert Storm—called Desert Shield—went on in Saudi Arabia and around the region. Finally, in December, the word came down that the “World Famous Fighting Rocketeers” and their mighty F-15Es would deploy to Al Kharj Air Base (which we called Al’s Garage).

There we would join up there with the 335th Fighter Squadron “Chiefs” which also hailed from Seymour Johnson AFB. The Chiefs proudly claimed to be “The World’s Largest Distributor of MiG Parts” from back when they flew the F-86 during the Korean War, and they had an impressive kill record.

The Genesis of the Strike Eagle

The Strike Eagle was an adaptation of an incredible Air-to-Air machine, the F-15A/B/C/D, and it still has the best kill-to-loss ratio of any fighter aircraft ever (debatably, 98 to 1). It was designed and first flew in the early 1970s. It thrives at medium-altitude, with a complex airfoil that gave it outstanding maneuverability unmatched by any other aircraft. It was so big that many classes at Luke AFB had their class photos shot with the entire class standing on top of the airplane in tennis outfits—it became known as the “flying tennis court.” As for its large visual signature, real fighter pilots aren’t afraid of being seen: We kill you as we spit in your face.

During the late 70s and early 80s, the F-111 was getting old, although I almost laugh at that now, since the oldest flying F-15s are approaching 40. In 1980’s, when the USAF started to pursue what became the Strike Eagle, the oldest F-111 was only about 20 years old.

The F-111 was a great penetration low-level day/night bomber but it had almost no air-to-air capability. I loved flying it, but it could be out-turned by everything. Low and fast it excelled marvelously. It was, however, an absolute maintenance nightmare. I think from my days on the staff at Air Combat Command at Langley AFB (if a judge told me to choose to serve on the staff in a non-flying job or go to prison—not sure what I’d do…) that the F-111 was 9% of the Tactical Air Force, but took up 25% of the budget. With this in mind, the USAF held a competition between a really cool looking delta-winged F-16XL and a heavily modified F-15D. The air-to-ground optimized Eagle was chosen.

(Author’s note: Israel was actually the first to put the concept of an air-to-ground F-15 to use operationally. Read all about it here.)

What made the “Mud Hen” special

The multi-role F-15E retained 100% of the capabilities of the “not a pound for air-to-ground” F-15C, sort of. They added two conformal fuel tanks (CFTs) on the sides of the fuselage that gave it a lot more gas, about an extra 8,500lbs of go-juice to be exact, but they also added weight and drag.

The CFTs could also carry up to 6,000lbs of weapons per side, or two 2,000lb weapons per side. Thus, a clean F-15E with CFTs up against an F-15C with two wing tanks would be hard pressed to win, especially as all that the F-15C driver did was live, eat, breathe air-to-air. We in the Strike Eagle community did 90% air-to-Ground and about 10% air-to-air. That ratio has varied over the years, but for us who went to Saudi Arabia so long ago, we were focused on bombs. The light grey guys (the F-15C wears a lighter paint scheme) can’t even say the word bombs, they call it “the B word” they hate it so much. They may be able to kill them one by one, but we can do that too plus we take the bad guys out by the hundreds with our payloads.

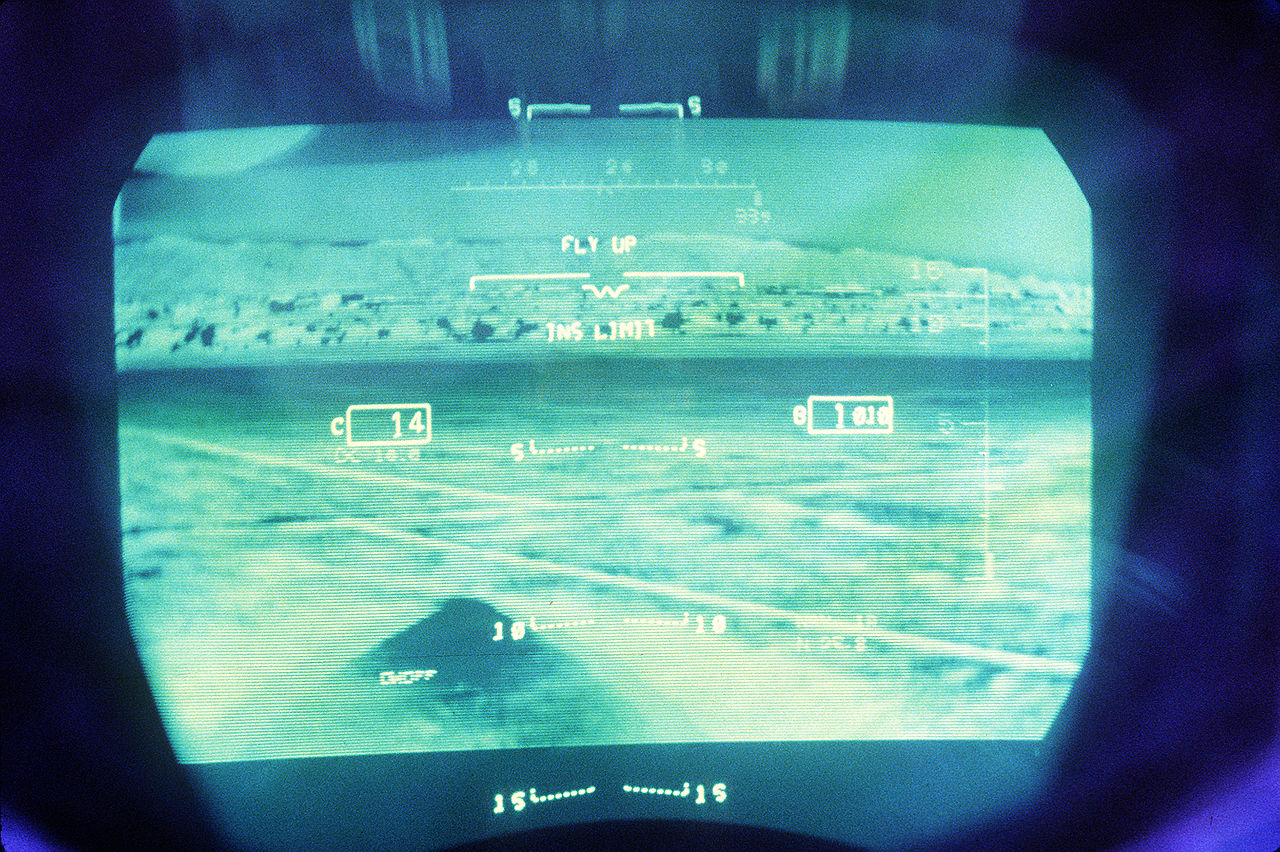

The best thing about the F-15E? It worked. You turned the radar on and it stayed on. You didn’t lose the INS (Inertial Navigation System) if you hiccupped. The TFR (Terrain Following Radar) always worked. Plus we had an IR (infrared) picture in our wide-screen HUDs that the light grey types lusted after, the massive HUD not the IR. Their’s was tiny and shriveled in comparison.

We had a WSO (Weapons Systems Officer). The light grey guys hate the idea of having company in the cockpit. That was life for us. Personally I found that when I worked with a good WSO I could fight better than by myself. I think I would have been a better pilot if forced to do it all by myself but when you put me with a WSO, we as a crew were better than I ever could have been with me by myself. Plus a huge advantage here, when I screwed up and was called into the boss’s office to be screamed at it hurt less as he was screaming at two of us instead of me alone. Misery loves company.

The F-15E had a fantastic advance know as Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). Basically a bunch of nerdy skinny guys with coke bottle eyeglasses and pocket protectors found that if they had the radar sweep back and forth a couple of times and then analyzed all of the pictures, checked them twice to see if we were naughty or nice, and then took the cube root of the square of the phase of the moon, that they could give us a picture of the ground that looked like it was taken from a satellite. It was incredible. Fences looked like fences. Buildings were square instead of blobs. Radar scope interpretation became much-much easier and bombing accuracy became much better.

To use the Synthetic Aperture Radar we had to move sideways to the target for a couple of sweeps. The greater the angle off the nose the area was we wanted to look at the faster the picture and the more accurate the radar picture was. This totally changed our target area behavior. In the F-111 you flew straight at the target as the WSO used the radar to find it. In the Strike Eagle we would fly at an angle to the target and turn direct only after the WSO found and designated it.

This was not that big of a deal really. We had to maneuver anyway to get minimum safe distance between each striking aircraft so we just integrated the need to map the target into our plan to attack from different directions at different times.

We would run in low. The F-15E could fly TFR down to 100 feet though I only used 200 feet to my eternal regret. Woulda-coulda-shoulda gone down to 100 feet at night just to say I did it. The lowest I ever flew at night in the F-111 was 500 feet, though I flew at 200 feet when flying under visual flight rules (VFR) conditions all the time.

Anyway, run in low then turn off when inside around 20 miles or so. This gave us our best resolution on the radar and I think the numbers were something like we could see objects as separate if they were a bit less than 10 feet apart. So, if you have two cars five feet apart they show up as one blob. If they were 15 feet apart they would show up as two blobs.

If the radar did not have enough grazing angle to see the target the WSO would direct us to climb. Once he had the picture we would turn target direct and drop back down to our attack altitude that was dictated by the bomb fuse combination that we were carrying.

Putting the Strike Eagle’s arsenal to work during Desert Storm

The standard for the start of the war was the MK-20 Rockeye cluster bomb which if I remember right had a timer fuse on it. A certain time after being dropped the MK-339 timer fuse would fire. The bomb would spin after release from the fins popping out at the back at an angle. When the fuse fired, the case split open, and the bomblets inside spread out due to centripetal acceleration. If you released too high the pattern was wider and if too low the pattern was narrower.

The bombs were dual purpose. If they hit something hard they would form a shape charge of plasma and burn through armor. If they hit something soft they would go off like a hand grenade and generate shrapnel. I loved Rockeye, great stuff, carried it the first few nights of the war and took out several Scud missiles with it.

By the end of the war we were primarily dropping CBU-87s, bigger at 1,000lbs than the 750lb Rockeye. That was nice because it had more bomblets. It was not nice because we could not carry 12 of them on the CFT’s, 6 per side, and carry wing-tanks as well, the top three bombs on each side were too close to the tanks. Thus we either carried less, six to be exact, or we carried less gas, a center line tank instead of up to 3 tanks, 2 on the wing plus the centerline tank.

The CBU-87 had a radar proximity fuse. As a result if I released it on or above the minimum altitude I got the exact same dispersion of the bomblets. This came into play after the second night of the war when we started dropping from what we used to consider the stratosphere, the mid-teens to high twenties (thousands of feet). We could still cover a huge area on the desert with a carpet of white fire. These were the best dumb bombs we used for the vast majority of targets we attacked during Desert Storm.

Laser Guided Bombs (LGBs) are visual flight rules only weapons. The laser is attenuated by visible moisture. Sometime you could use a ground laser beneath a cloud deck, the aircraft could drop the bomb ballistically and the guy on the ground would guide it in by illuminating the target with his laser.

At the start of the war we had Paveway II LGBs in 500lb (GBU-12) and 2000lb (GBU-10) configurations. It didn’t matter to the aircrew which he carried as they were identical in employment. We did not start using them until a bit into Desert Storm as we only had nine LANTIRN targeting pods for 48 aircraft. We were up to 24 pods by the end of the war. Because of this, we always used them from medium altitude in one of two ways.

If the aircraft was lasing (painting a target with a laser) for itself, it would drop the bomb and immediately crank off about 45 to 60 degrees while continuing to lase the target. I think usually we would use a “delay-lase” tactic though, where we would not turn the laser back on after release until 15 seconds or so to impact. This was to keep the bomb falling ballistically. If you had the laser on full time then as soon as the laser was seen by the seeker it would point straight at the target and cause the bomb to come in at a slightly shallower angle than it would with a delayed laser operation. Steeper meant faster and more energy to maneuver to steer to the laser spot. I have actually seen slow motion footage of bombs hitting short with the bomb at a very nose-high angle of attack as the seeker struggled to keep on target and the bomb got too slow.

By cranking sideways the laser spot would remain on the same side of the target as the bomb, usually. Even when you are lasing the target at almost 90 degrees you would usually have enough laser “splattering” for the bomb to see it. Round oil storage tanks could be tough though. Also, you could end up lasing the side of a building the bomb couldn’t see so it took a bit of artistry to know the right run-in angle and crank-off angle.

The other advantage of cranking-off was avoiding the very disorienting roll of the seeker head as it passes through the vertical. Not only that, but since the LANTIRN targeting pod had the seeker head on the front of the pod’s body, the ability to see to the rear was extremely limited. I have seen a lot of targeting pod video from the war and several times you can see where the laser stops prior to bomb impact due to this. With good crew coordination the pilot could quickly turn back toward the target and roll back out allowing the pod’s laser to stay on target.

Another tactic we used was buddy lasing. In this case the poor wingman (always me as I was a wingman the entire war) who had no targeting pod would drop the bomb ballistically so that his flight lead could have all the fun and be the hero in taking the target out. I kind of felt like the sparring partner for the heavyweight fighter. I did a lot of work with little satisfaction. I know, yes I would like some crackers and cheese to go with my whine.

The flight lead would fly several miles behind the wingman and be able to fly straight towards the target the entire time. This actually gives the bomb the absolute best laser spot as it is more in line with the flight path of the bomb the entire time.

So how big is the laser spot? We had some footage taken out at the Utah test range that actually filmed our LANTIRN targeting laser on the target as we dropped bombs. If I remember right it was a 2 story target building. The laser spot covered most of the entire building when the bombs hit! We were several miles away and it showed how even lasers diverge over distance. The seeker on the bomb tracks the center of the spot so even though it was a big spot we still got good guidance with it.

We also carried the standard MK-82 500lb bombs and another favorite of mine, the MK-84 2,000 pounder. I had one mission against a cloverleaf in the desert of Kuwait with five 2,000lb bombs. We could see the shock-wave as they blew up, even on the darkest night.

We own the night

We used the FLIR (forward-looking Infrared) in the LANTIRN Navigation pod to fly formation at night. Thus in a two ship or more we would fly a train with each wingman being two to four miles behind the aircraft in front. This allowed the radars to be in scan mode rather than remaining locked on to the aircraft in front of it.

I think most flight leads preferred to fly in black-hot on their HUD. I preferred white hot as it was easier to see the aircraft as a white dot than a black dot for me. Our leads tended to criticize us but most of us just shrugged and continued to do what we wanted to as it was our choice and we were the ones who would be embarrassed if we didn’t stay in position. Remember the wingman’s creed – “two, joker, bingo, mayday, and Lead you’re on Fire.” Other than that shut up and color. Be in position and do what you’re trained to do. That way the formation is strong. A weak wingman is worthless.

At that time we had no data-link. Big weakness. All targets passed to the Strike Eagle after takeoff were done verbally. We worked with E-8 JSTARS a lot. They had a SAR radar like ours but theirs could take detailed pictures from much greater ranges. They would then try to talk us onto targets.

They would give us the coordinates, oh yeah also no GPS in the F-15E back then, so coordinates could be up to a half mile or more off. They would then verbally describe the targets they were seeing. “A group of six tanks in a crescent moon oriented towards the northwest.” Sadly many times we would just find some returns near the coordinates they gave and drop our bombs on them.

This was really a problem when we were buddy lasing. Making sure we were on the same target took a lot of time. Of the few buddy lase missions I flew I would usually bring back several of the LGBs. We just ran out of gas before lead dropped all of his and then started to talk us onto a target to drop ours.

I don’t remember if the original LANTIRN targeting pod had the ability to see another laser. This is a huge benefit now. The A-10 had this way back when it first flew with the Pave Penny system. Another aircraft or a ground controller could put a laser out on a target and a pilot would get an indication on his HUD showing where the laser-spot is and thus would be able to find the target immediately. This didn’t matter much for us during Desert Storm as I don’t think we flew with more than one targeting pod in a formation for the entire war.

The Strike Eagle ages beautifully

Starting in 1996 Saudi Arabia bought their version of the F-15E, the F-15S. It was downgraded slightly from the USAF’s version. I think originally they weren’t going to get the weapons stations on the CFTs and were going to use BRUs (bomb racks) and MERs (multiple ejector racks) on the wing. They have the weapons stations on the CFTs now, although I just do not know if they had them originally. I will talk though about the F-15S today – the F-15 I wish I would have had 25 years ago.

GPS. Enough said. Hard to imagine living without it.

With GPS comes JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition), a dumb bomb made smart with a GPS guidance kit. Wow. That bomb alone is the difference between fighting in the Stone Age and now. All weather accuracy without the need for post target lasing. True launch-and-leave capability.

JDAM offers a much larger effects footprint. One pass, multiple Desired Mean Point of Impacts (DMPIs). I only attacked one target per pass in Desert Storm. Now, with JDAM, I could attack 12 or more targets on one pass. That is a game changer.

Data-link. I never ever had it but always wanted it. No more “bogey, Manny, 090 for 65 Westbound.” Okay, now I have to know where Manny is, then where am I in relation to Manny. Then take that information I just heard and mentally plot it out and do a fix-to-fix in my head to figure out where he is relative to me. Hmmm. Angle of the something or other squared times… Remember the movie Mars Attacks when the Country Western music is played and the Martians’ heads explode?

Now with the data-link you look down at your display and see exactly where Manny and pretty much everything else is, in color, and relative to your own position. Remember when your teacher told you how nice it was to share? Now you get to share all sorts of stuff, radar, pictures, home movies, the list goes on. Data-link is as much a game changer as GPS.

Targeting Pod mechanized for air-to-air combat. My neighbor back in the 90s at Seymour Johnson was Ziggy Dahl, an instructor WSO in the Chiefs. He used the targeting pod to do air-to-air back before it was optimized to do it. As like most modern fighters of the day we had pulse doppler radar and everyone knows thatif you fly perfectly perpendicular to the air-to-air radar locked onto you then you will disappear. Klingon cloaking device on! Our radar could only look to 60 degrees back then, later a bit more, but still way less than 90 degrees. Solution, use the targeting pod which gave you +/- 1 degree accuracy. It worked like a champ but was hard to do.

I understand now that the targeting pod cues to expected position of the target without a ton of work on the WSO’s part (Author’s note: this technology is now being fully integrated also on American ANG F-15Cs equipped with SNIPER targeting pods). Do a hard turn and blank out the targeting pod and it will track where the bogey should be and return to that point in space when you un-blank the pod. Back when I flew it the pod would go stupid if it broke-lock and was blanked out.

AIM-120 AMRAAMs on the wing rails above the fuel tanks. All we had during Desert Storm was the AIM-9L Sidewinder. Great missile but it is a pistol in a rifle fight with the Mig-29s we were facing. To carry the AIM-7 Sparrow we would have to give up bombs on the conformal fuel tanks. In hindsight we would have killed five or more MIGs during the first night if we would have had the flight leads go in with one conformal carrying six MK-20 Rockeyes and one conformal carrying two Aim-7Ms. Oh well.

Now the Strike Eagle always has claws on every flight. Long-range claws. Approach at your own risk claws.

Then and now

Perspective time. Last year I returned to that small government school in central Colorado for delinquent boys and girls called the United States Air Force Academy for my 35th reunion. This was the first reunion I attended. It was a great time with great friends.

35 years prior to my graduation in 1980 was 1945. Jets were rare then with the Lockheed P-80 shooting star designed in 1943 and that was it, and it was not used in WWII. The Germans had a couple, the British had the Glouster Meteor, etc. Still, the piston engine was king. The Spitfire, the Mustang, the B-29 and so on. In 1980, 35 years later, the USAF was flying the A-10, the F-16, the F-15C, and the B-52. Now in 2016, 36 years after 1980, the USAF is flying the A-10, the F-16, the F-15C, and the B-52. Hmmmm.

The difference? GPS and data-link, as well as persistent ISR (Information, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) for the combatant commander and individual warriors. We now have constant ISR on the battlefield. The only ISR we had in Desert Storm was JSTARS and Compass Call, and maybe Rivet Joint, but that was classified way above my head. U-2 and SR-71 too but not for us at the operational level. Today the coverage of the MQ-1 and MQ-9 and other UAVs on the battlefield gives incredible situational awareness available to the average pogue that was not available 25 years ago.

We could destroy every single target hit during the entire Desert Storm with one squadron of F-15Es or F-15Ss today. Precision attacks on multiple targets per aircraft per pass, day, night and in any weather.

Would we? Doubtful. We have more capability today but are hitting far less targets due to the fear of collateral damage – but that is another discussion for another day.

A huge thanks for Richard Crandall for sharing his incredible experiences and perspectives with us. Stay tuned for the second installment where he details his time flying General Dynamics swing-wing bomber, the iconic F-111, at the height of the Cold War.

Contact the editor Tyler@thedrive.com