The U.S. Navy’s Naval Surface Warfare Center, Dahlgren Division, or NSWCDD, has created a new division specifically for researching and developing high-power microwave (HPM) directed-energy weapons. Unlike lasers, which the Navy also is investing in heavily, this emerging class of weapon systems uses bursts of microwave energy to disrupt or destroy the electronics inside various enemy systems, including drones, small boats, and missiles. As asymmetric threats continue to pose threats to high-value military assets, these weapons could soon provide the Navy with an extra layer of defense if its research and development efforts pan out.

Prior to this reorganization, one NSWCDD research division was responsible for both laser weapons and HPM. In a Naval Sea Systems Command press release announcing the creation of the new division, Weapon Systems Division Head Kevin Cogley says, however, that lasers and HPM weapons can actually complement laser weapons, rather than compete with them.

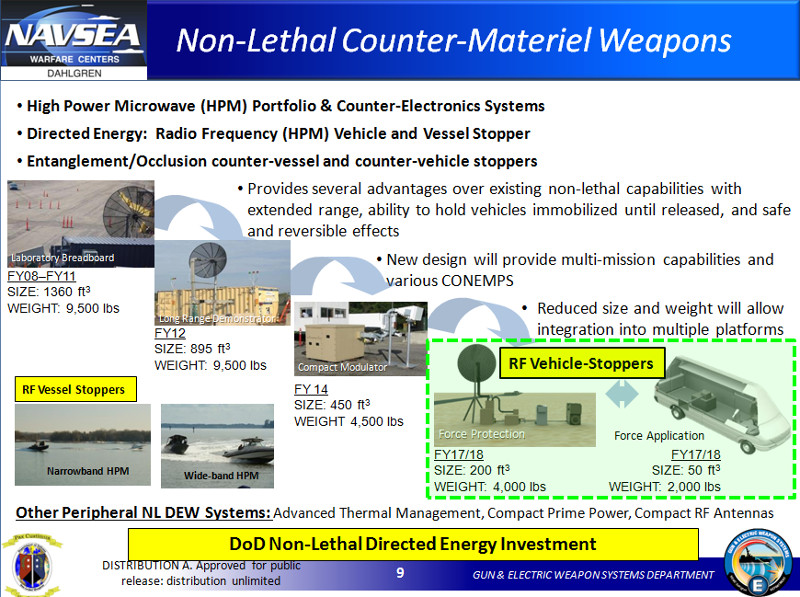

“HPM and lasers work in parallel in a lot of areas,” Cogley said. “One thing that is unique in the HPM arena is that we can have graduated effects. In HPM, we can have a range of effects on target – from basically jamming a device to physically destroying electrical systems.” While this class of weapons isn’t new per se, continuing technological advances in miniaturization and efficiency are making microwaves attractive for a wide variety of new applications.

Cogley also briefly outlined the unique benefits and capabilities that microwave weapons offer. “HPM is very different than many other weapon systems because in many cases you may not see any outward physical effects during an engagement but will see nearly-instant results on the target’s operational performance,” Cogley said. “Using HPM, we can give our Sailors a capability that could be a desirable alternative to firing a kinetic weapon.”

One of the most attractive aspects of high-power microwaves and other directed energy systems is that they offer a much lower cost-per-shot than kinetic weapons, which can sometimes total in the millions for a single munition. Directed energy weapons offer another unique advantage over kinetic weapons: magazine depth. Whereas kinetic weapons have fixed magazine sizes and must be physically reloaded, a HPM weapon could have an unlimited magazine, at least in a physical sense.

In addition, HPM systems can potentially operate in a less than lethal manner, meaning they may be able to disable manned vehicles them without directly harming the occupants inside. Such a capability could potentially alter the rules of engagement and allow Navy vessels to engage and disable small manned craft without inflicting physical harm on their occupants.

Aside from engaging surface vehicles, HPM weapons are well-suited for use in counter unmanned aerial systems (cUAS) roles. Small drones, which are becoming more and more of a threat to a wide variety of Navy and DOD assets, are difficult for some air defense systems to track and target. Unlike lasers, which typically fire a focused beam for short periods of time, HPM weapons can fire wide-area cone-shaped beams, enabling them to engage multiple UAS at once.

“The fact that you can simultaneously track and immediately move to the next target to address not just a swarm, but multiple swarms, is a big advantage,” Don Sullivan, chief technologist of directed energy at Raytheon’s Missile Systems business, said in 2018 regarding one of its HPM systems supplied to the Air Force. These wide-area effects and speed of light capabilities mean that HPM weapons could even engage targets that maneuver too rapidly for kinetic interceptors to hit.

For those reasons, and potentially more that are not disclosed, Navy Senior Technologist for Directed Energy Dr. Frank Peterkin said that HPM and other directed energy weapons “provide effective and affordable ship defense solutions that address growing threats to our ability to project power and protect freedom of the seas.”

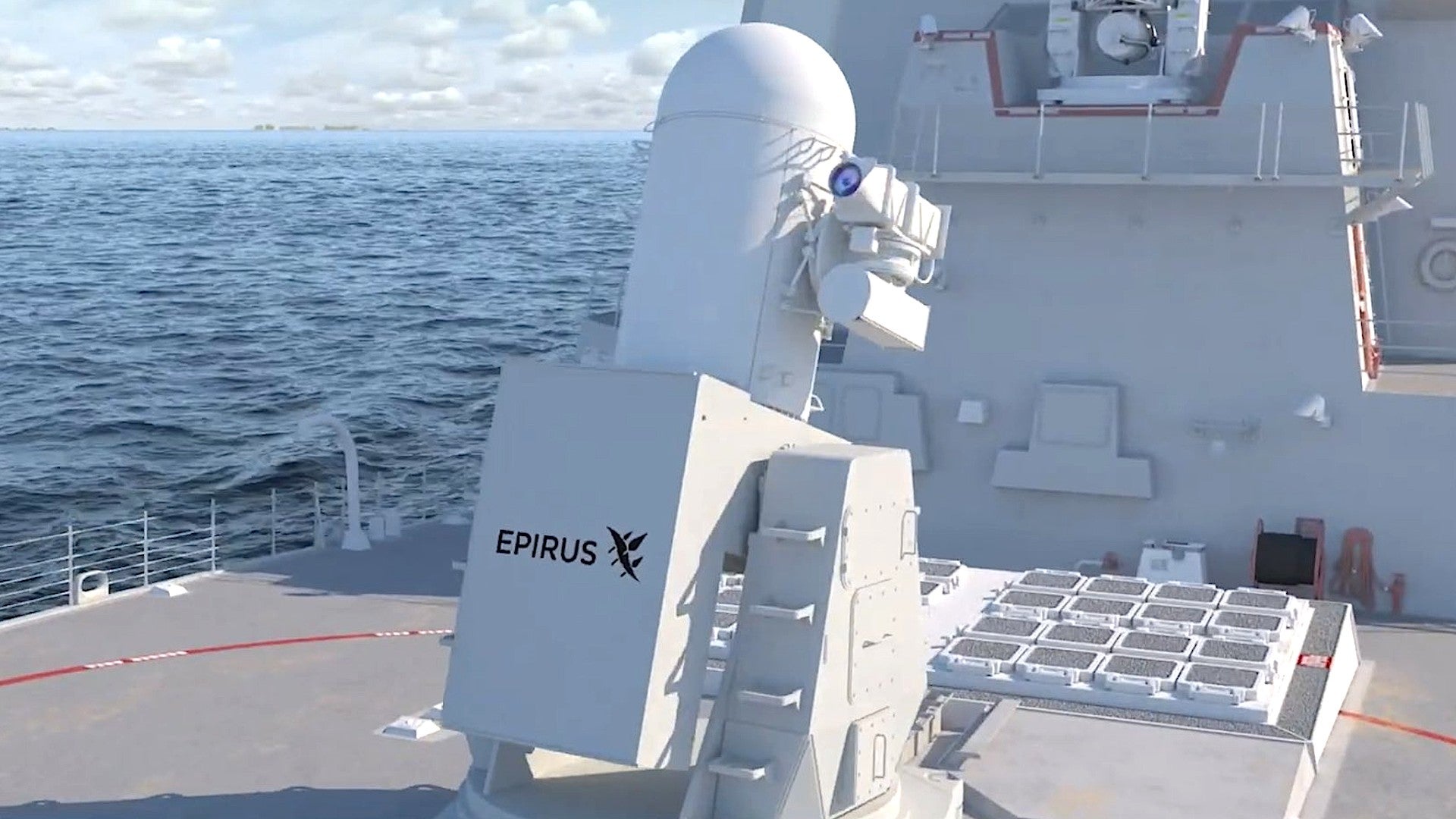

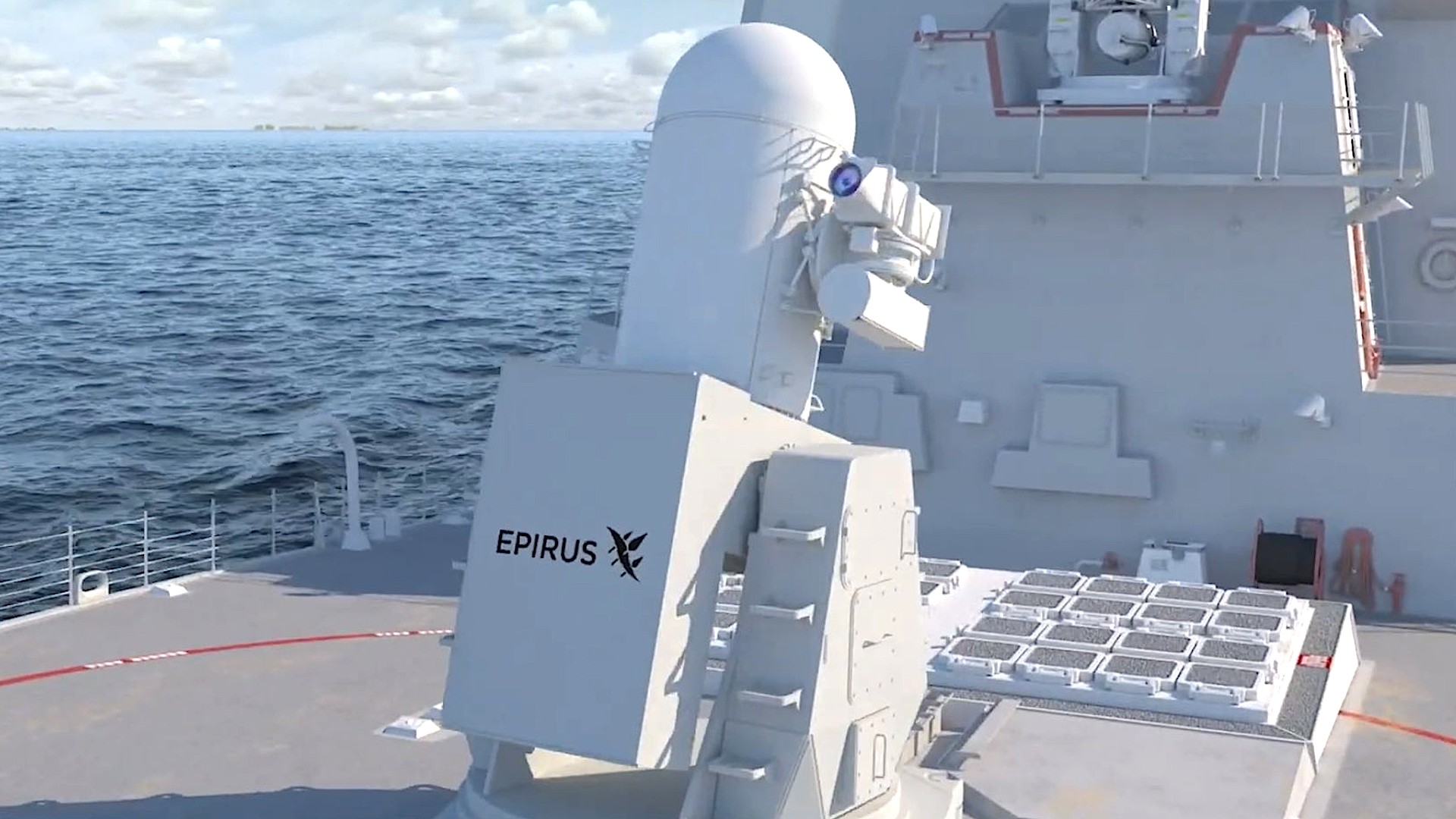

According to NAVSEA’s announcement of the reorganization, this “sets NSWCDD ahead of the curve for HPM testing.” With this new reorganization, NSWCDD becomes one of only two Department of Defense facilities with a dedicated HPM division alongside the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Directed Energy Directorate at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico. According to Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), these two laboratories “collaborate on the largest HPM projects in the country, offense applications, counter unmanned aerial systems and integrated air defense topics.” HPM systems are also being eyed for missiles with non-kinetic payloads such as the joint USAF/Navy HiJENKS project, as well as for use in space aboard anti-satellite systems, although these technologies remain highly classified.

The Department of Defense (DOD) is not alone in its efforts to field HPM weapons, as potential peer-state competitors are actively pursuing them as well. They still remain one of the murkier areas of military research, however, and a high degree of confusion and misinformation surrounds the topic. There are plenty of downsides to directed energy weapons like high-power microwaves, too, including possible downtime between shots, atmospheric and meteorological interference, electromagnetic shielding countermeasures, and range constraints.

Still, given the successes that various DOD laboratories have already had in testing high-power microwave systems for use in air defense systems and counter-drone technologies, it’s easy to see why the Navy is placing a higher emphasis on HPM and standing up a specialized research division to develop them. The need for defense systems to deal with the new threats posed by small unmanned vehicle technologies is pressing, one the Navy is currently facing on a regular basis.

HPM systems are well suited to deal with these growing threats, and could potentially defend against more traditional aerial threats like incoming missiles, as well. It’s likely that in the very near future, these directed energy systems could complement existing air defenses and close-in weapons systems in protecting U.S. Navy ships patrolling the high seas.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com