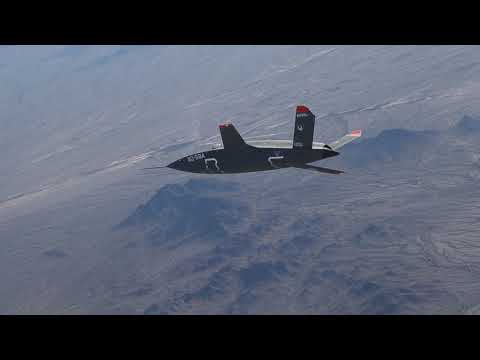

Kratos has released the first rendering, seen at the top of this story, of the unmanned aircraft it is developing under the U.S. Air Force’s secretive Off-Board Sensing Station program, or OBSS. While details about the drone remain limited, we do know there is a heavy emphasis on scalability, modularity, and affordability, and that it will leverage advanced design and manufacturing concepts to help achieve these goals. There also may be hints as to what it may be intended to do thanks to recent remarks from one of the company’s executives.

Breaking Defense

was the first to publish the artist’s conception of Kratos’ OBSS design yesterday, along with an interview with Steve Fendley, the President of the company’s Unmanned Systems Division. In October, the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) awarded Kratos a contract to build and flight test at least one OBSS prototype. General Atomics also received a functionally identical OBSS contract from AFRL, though the value of their deal was different.

After seeing the piece from Breaking Defense, The War Zone reached out to Kratos to see if any additional imagery or other information relating to the company’s OBSS design might now be releasable and was informed that there is not any.

From what we can see in the rendering, the drone has a stealthy design with a noticeable continuous chine-line that wraps around the fuselage, as well as a serrated top-mounted air inlet and shrouded engine exhaust. It has a simple swept wing and a broadly splayed v-tail. There are some similarities, especially in the rear two-thirds of the design, to Kratos’ XQ-58A Valkyrie drone, but the OBSS lacks the cranked wing of that design and its tail is differently configured.

There are very broad echoes in this design of other existing manned and unmanned stealth aircraft. Some examples include the Scaled Composites Model 437 and the Model 401 “Son of Ares” from which it is derived, the General Atomics Avenger, Boeing’s MQ-25 Stingray and the designs that had led up to it, and the EADS Barracuda, as well as the lambda-winged Joint Advanced Strike Technology fighter jet concept.

The Kratos OBSS design seems to trace some of their broader elements to Northrop’s Tacit Blue stealth demonstrator. However, Tacit Blue featured a complex flush air inlet on top of the fuselage something that is not found on Kratos’ OBSS design.

There is no indication, of course, that Kratos’ OBSS drone is directly based in any way on any of these previous designs. The company has previously stressed to The War Zone that this unmanned aircraft is a distinctly new entry in its portfolio, but has so far been unable to provide more specific information about the design’s features or its origins.

There are virtually no details available yet about its expected performance or other capabilities, either. In the interview published by Breaking Defense, Fendley, the President of Kratos’ Unmanned Systems Division, was very careful to speak in generalities, rather than about what OBSS might be capable of specifically.

“In general, that’s correct. However, there’s certainly the possibility of having an attritable aircraft carry an exquisite sensor,” Fendley said in response to a question about whether OBSS would carry a basic payload to help keep its costs down and make it less of a problem if it were to be lost on a mission. “For example, we could integrate a $5 million-$10 million sensor on one of our systems. But that specific tail number, in all likelihood, would not be performing an attritable mission, even though technically the expensive sensor would be on an attritable aircraft.”

Defining the term “attritable” can be difficult. The War Zone has generally described attritable platforms – drones or anything else – as ones designed with a focus on balancing capabilities against lower costs to produce something capable of performing certain missions in higher-risk environments where commanders might be disinclined to employ a costlier and more technologically advanced asset. Fendley, in this new interview, used a definition of a system that costs “$2 million to $20 million per copy” and “provides a high-performance-versus-cost-system solution that the user can afford to potentially lose at some non-zero rate.” The Kratos’ XQ-58A, which the company has long said it hopes will eventually have a unit cost of around $2 million as production expands, would be at the lower end of that target price range.

“The other thing about attritables that’s different from legacy UAS, outfitted with their exquisite sensors, is distributed lethality in the case of weapons and distributed sensing in the case of sensor missions. Maybe you have a very comprehensive sensor capability because you have 10 of these attritable aircraft carrying non-exquisite EO/IR systems, for example,” he continued. “You’re fusing the data you get from those aircraft remotely, and the picture you get is very precise. Now let’s say that three of those aircraft get shot down; you still have a very high-quality picture and good intelligence because you have a seven-sensor baseline instead of just one very expensive sensor. The distributed method helps reduce cost and increase mission effectiveness and survivability.”

“Speaking of attritable aircraft generally, not necessarily OBSS, we’re talking about sensor extension and range extension. Let’s say a manned system has particular sensors, such as EO/IR, and the goal is to increase standoff range against a particular threat,” Fendley added when asked to describe a notional OBSS mission. “A handful of attritable aircraft could fly in a teaming formation with a manned aircraft. As the mission progresses, the pilot in the manned aircraft would say, ‘OK, this is as far as I’m going toward the threat because we’re getting close to a contested environment or risk area for me.’ The unmanned aircraft would then be tasked with continuing into the contested environment/risk area and collecting and sharing data to better inform the mission and the warfighter.”

Though we can’t say for sure, based on what we know now, one mission set the OBSS platform seems as if it would be particularly well suited to perform would be acting as a distributed sensor network to help manned fighter jets, a possibly other advanced unmanned platforms in the future, find, track, and engage threats. In this role, an OBSS drone could carry an infrared search and track (IRST) sensor system to detect targets passively by their thermal signature, rather than using a radar that could alert opponents to the unmanned aircraft’s presence. Furthermore, IRST systems have the benefit of not being hampered by any radar-absorbing or deflecting qualities found in the design of a stealthy enemy aircraft or missile or by radiofrequency jamming.

We know that at least one Kratos UTAP-22 has been flying with what appears to be an IRST system as part of the Air Force’s Skyborg program, which is also managed in part by AFRL. Skyborg is focused on the development of an artificial intelligence-driven “computer brain,” along with a suite of associated systems, that will be able to operate semi-autonomous “loyal wingman” type drones flying networked together with manned aircraft, as well as fully autonomous unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAV) potentially in the future. Renderings of notional Skyborg-equipped drones that the Air Force has released over the years feature nose-mounted sensors that also appear to be IRST systems, too.

General Atomics, the other company involved in the OBSS project, has also test flown Avenger drones with underwing IRST pods during Skyborg tests and as part of other tangential efforts with a clear focus on expanding manned-unmanned teaming capabilities in air-to-air combat scenarios.

Having multiple IRST-equipped drones networked together would offer significantly expanded capabilities over a single platform, manned or unmanned, equipped with this kind of sensor system. A single IRST source can determine the bearing of a target, but can have a hard time figuring out how far away it is. Just adding a second IRST source to the mix allows for a more ready determination of the range to a contact via triangulation. Having more sensors only further improves the fidelity of those tracks and expands the total formation’s ability to track many targets at once.

Beyond that, relatively small stealthy drones using passive IRST sensor systems could be challenging for an opponent to detect and even more difficult to try to engage, all while they are providing targeting data to other friendly platforms. These drones could be equipped with other sensors instead of IRSTs, too, such as small, but capable radars, or even electronic warfare payloads, allowing for more complex tactics to be put into play, but pushing IRST capability forward over the battlefield seems like the most logical application for such a concept, at least at first. This would drastically enhance the lethality and survivability of manned and unmanned types that such a group of OBSS aircraft would be designed to support. This distributed “off-board” sensor capability is possibly where the name OBSS origniates from. Once again, this is all speculation based on what we know so far.

Regardless, there certainly seems to be some kind of sensor in the nose of Kratos’ OBSS design. The artist’s conception is cropped in a way that looks deliberately intended to avoid giving a full look at the front of the drone. On closer inspection, there also appears to be a fairing extending back along the tip of the nose that could further indicate that there is something sticking out of the front.

The OBSS program’s biggest focus may well turn out not to be in any particular set of capabilities, but in the design and manufacturing concepts that are employed to build these unmanned aircraft. AFRL has previously said that the project aims “develop and flight demonstrate an open architecture aircraft concept to achieve the goals of rapid time-to-market and low acquisition cost” and that the drones “will be designed for limited life in terms of years, not decades, with no depot maintenance and limited field maintenance considerations.” The contracts the Air Force awarded to Kratos and General Atomics both specifically mentioned “goals of rapid time-to-market and low acquisition cost.” Beyond that, “the demonstration vehicle will incorporate ‘scalable and responsive’ manufacturing techniques, with future variants to be built from a common, government-owned architecture based on emerging requirements,” the introduction to the interview with Fendley on Breaking Defense said.

“The category/class called ‘attritable aircraft’ really refers to an affordability objective solution to a UAV problem/need without an expectation for the aircraft to be in service forever,” according to Fendley. “This class seeks an optimization of capability versus cost and life. It’s certainly not the intent to use these assets once and throw them away, but they are also not intended to remain in service for 100 years like the B-52 for example.”

“To be suitable for this mission and to meet this need, attritables are made with design and manufacturing tradeoffs that ideally maximize capability in each performance/functional area and throughout the aircraft’s lifetime right up to the knee in the curve where the price would increase substantially versus performance,” he said. “Attritable aircraft provide a mass advantage in conflict, which is commonly assessed as the current need to be able to meet near-peer adversary threats. They solve the mass equation because we can afford to acquire and deploy large numbers of attritables.”

This is all very much in line with an in-depth discussion The War Zone had with Fendley back in September about attriable designs, affordability, and future trends in unmanned aircraft development on the sidelines of the Air Force Association’s annual Air, Space, and Cyber Conference, which you can find here. Then, as in his new interview published by Breaking Defense, he added that he felt that Kratos was particularly well suited to meet these various intertwined demands.

“Kratos’ family of attritable aircraft – the XQ-58A Valkyrie, the UTAP-22 Mako, the Air Wolf, several classified systems, and now, our proposed solution to OBSS – fit at the very low cost end of those ranges,” he told Breaking Defense. “In general, our sweet spot is something that’s in the high-subsonic speed range, high-maneuverability G range, and high survivability with respect to a contested environment. We have absolutely become experts at developing and producing high-performance subsonic, affordable, jet, unmanned aircraft that include a range of autonomy capability.”

“Affordability is what is most essential to enable us to compete with the other primes,” he continued. “As a company, speed, agility, and affordability are our discriminators. Because of our size, selling a number of $1 million or $3 million aircraft a year is a solid business model for us, so we are adequately incentivized even at these price points.”

It’s not clear when Kratos’ OBSS design, or the one from General Atomics might fly for the first time, but the contracts from AFRL cover an initial phase of work that ends next October. One company is expected to proceed to the actual flight testing portion of the program after that, with that work continuing into 2024.

As the first phase of the OBSS program progresses in the coming year, we may begin to learn more about the project’s overall objectives and the two competing designs.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com