South Korea and the United States are working on a new joint war plan as the two allies seek to keep pace with North Korea’s rapidly developing military capabilities. The new operational planning will also respond to the growing military threat presented by China, with the aim of increasingly including South Korea within a broader regional posture, as Seoul also looks to its own security challenges beyond the peninsula.

Details of the war plan have been announced this week as part of the 53rd U.S.-Republic of Korea Security Consultative Meeting, or SCM, which included today’s meeting between U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and his South Korean counterpart Suh Wook. In the first such meeting since U.S. President Joe Biden took office, the two officials confirmed they would together look at new ways to deter an increasingly assertive North Korea, amid Pyongyang’s spate of new strategic weapons developments.

The evolving war plans for the Korean peninsula come against a backdrop of U.S. overtures toward Pyongyang with a view to resuming talks, so far without success. Defense Secretary Austin again stated that diplomacy was the best approach to dealing with North Korea but at the same time the U.S. military is reinforcing its presence in the South by stationing more units there.

“This is the right thing to do,” an unnamed senior defense official told Voice of America. “The DPRK has advanced its capabilities,” the official added. “The strategic environment has changed over the past few years.” The same source noted that there is no deadline currently set for completing the updates to the war plans.

New military capabilities showcased by North Korea in recent months include tests of a cruise missile, a short-range ballistic missile, a submarine-launched ballistic missile, and a claimed hypersonic glide vehicle. At the same time, South Korea has also been working on advanced military development as well, and their ability to contribute new capabilities to the overall plan is considered an important part of the update.

The Pentagon had previously announced its intention to permanently base a U.S. Army AH-64 Apache attack helicopter squadron and artillery division headquarters in South Korea, while troop numbers in the country will remain stable at around 28,500. This is despite the latest defense authorization bill having removed a lower limit clause on numbers of U.S. troops on the peninsula, which had led some to predict the figure may come down.

The United States has reinforced its commitment to providing extended deterrence to South Korea, including nuclear and conventional weapons as well as missile defense capabilities. However, with an upcoming review of nuclear weapons policy, it’s possible that the role of nuclear weapons in a conflict on the peninsula could be subject to change, with reports of the possible introduction of a ‘no first use’ policy in this scenario.

At the same time, there has been pressure from some hawkish elements in the United States and South Korea to reinstate U.S. tactical nuclear weapons, or nuclear sharing, in the South as a counterweight to the North’s nuclear program. The U.S. and South Korean governments have so far proven resistant to these calls, Washington ruling out the idea in September.

In terms of U.S.-South Korea cooperation, the two countries have agreed to update the Strategic Planning Guidance underpinning their strategy for a potential conflict on the peninsula. This was last done in 2010 when the primary threat posed by Pyongyang was its artillery and other conventional weapons.

At the same time, the combined military command is being reviewed, heralding a potentially highly significant change for South Korea. Currently, during wartime, South Korean troops would fall under U.S. command, but Seoul has been increasingly pushing for operational control (OPCON) of its own forces.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in had previously stated the goal of achieving OPCON before he leaves office next year, but this three-stage program has been postponed due to both the COVID pandemic and North Korean missile developments. However, the topic of OPCON transfer feasibility will be reviewed again in 2022, with a view to declaring this concept fully operational sometime in the middle of this decade.

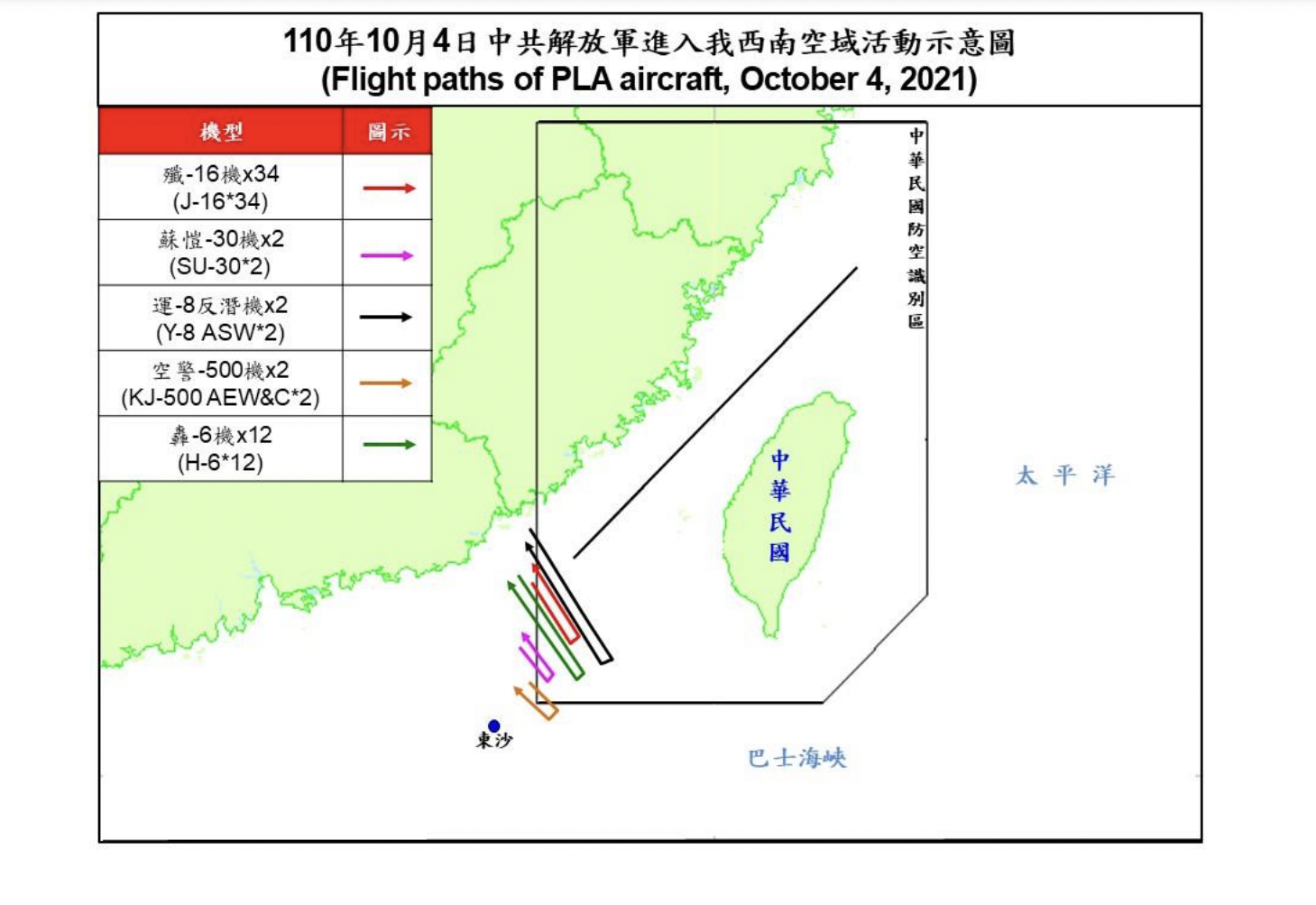

As well as pointing to the need for a revised military strategy to address North Korea’s capabilities, the joint statement from the two defense chiefs identified “the importance of preserving peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait,” a reference to the body of water between Taiwan and mainland China in which the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been notably active in recent months.

This is the first time that the strategically vital Taiwan Strait has been referenced in a joint statement from the South Korean and U.S. defense chiefs, although the same topic was discussed between Biden and Korean President Moon Jae-in when they met in May.

This is in line with the Pentagon’s Global Posture Review that makes the case for working alongside allies and partners to deter potential “military aggression from China and threats from North Korea” as part of a focus on the Asia Pacific region. Indeed, it’s been confirmed that the Pentagon consulted with South Korea as it drew up the still-classified review.

Under the revised posture, South Korea will be expected to contribute to efforts to ensure security and stability across the region as a bulwark against perceived Chinese aggression and its extensive maritime claims. This also tallies with certain developments within Seoul’s military, including plans to field true aircraft carriers, in addition to amphibious assault ships, and the recent establishment of a rotary-wing aircraft group within the ROK Marine Corps, or ROKMC, as that service develops its amphibious capabilities.

“We see [South Korea] now as a net provider of security not just on the peninsula but across the region,” the unnamed senior defense official told

Voice of America. This means the two countries will be “looking at ways where we can coordinate our defense cooperation in the region, and specifically capacity building throughout the region.”

“The ROK-U.S. alliance is evolving,” South Korean Minister of Defense Suh Wook said. “The strength of such a great alliance will backstop the efforts towards denuclearization of and establishment of permanent peace on the Korean Peninsula, and also contribute to a stable security environment in northeast Asia.”

In fact, the kinds of high-end but relatively small and highly mobile forces typically fielded by South Korea could lend themselves particularly well to the new types of U.S. warfighting doctrine being prepared for a potential future conflict in the Asia Pacific. In particular, the U.S. Marine Corps recently unveiled its “stand-in forces” concept that envisages small forces that would respond to Chinese “gray zone” aggression, actions that fall below the threshold of all-out combat but which could encompass a range of activities, including cyberattacks, assassinations, or occupation by unofficial militias.

The U.S. Marine Corps describes “stand-in forces” as “low signature, mobile, relatively simple to maintain and sustain forces designed to operate across the competition continuum within a contested area as the leading edge of a maritime defense-in-depth in order to intentionally disrupt the plans of a potential or actual adversary.”

The South Korean military is already very familiar with some of the kinds of “gray zone” tactics that might be deployed by China while remaining just below the level of a full-scale conflict. For its part, Seoul has long faced the threat of North Korea’s huge special operations component that would be expected to perform unconventional warfare, including being inserted covertly into South Korean territory by An-2 biplane transports, miniature submarines and other covert watercraft, and other means.

The U.S.-South Korean statement on China comes in the same week that Suh Hoon, director of South Korea’s National Security Office, visits China to discuss regional issues. This reflects the difficult balancing act that Seoul has traditionally played as it seeks to continue a working diplomatic relationship with Beijing while cooperating closely with the United States on defense matters. It also remains to be seen how Beijing responds to this new South Korean posture and whether it seeks to engage with Seoul.

However, the signs from today’s meeting of defense ministers, as well as the wider ramifications of the SCM, clearly point to an ambition to have South Korea play a much-expanded military role not only to face off the threat from the North but to support U.S. policy across the wider Asia Pacific.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com