A senior U.S. Air Force official has outlined their vision of the kinds of air-to-ground weapons that the service will use in the future, with less expensive munitions and “swappable” payloads marking a significant shift away from the specialized munitions commonly used today. When it comes to destroying targets on the ground, the Air Force of the future should rely on a new generation of more versatile weapons for most of such tasks, with a smaller number of high-speed and bunker-busting munitions to take out particular high-priority objectives.

Major General Jason R. Armagost, the Director of Strategic Plans, Programs, and Requirements, at Air Force Global Strike Command, was speaking at a webinar hosted by the AFA Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, a video of which you can find here.

Discussing a Mitchell Policy Paper, Affordable Mass: The Need for a Cost-Effective PGM Mix for Great Power Conflict, written by Mark A. Gunzinger and published online yesterday, Armagost described the Air Force’s aim to shift from what he termed weapons “exquisitely” tailored to fit a particular purpose to “generic weapons with selectable effects.”

That goal should be achieved by introducing new kinds of “low-cost, swappable” payloads, allowing the same basic weapon to be adapted for a range of different targets and flight profiles. Advanced submunition payloads would also potentially allow a single weapon to attack multiple targets.

“Everything has got to be multi-domain,” Armagost said. “We can’t think in strict terms of, ‘This weapon is designed for this specific target.’ It’s inherently multi-mission, it has to have that flexibility built-in.”

As well as munitions with swappable payloads, new air-to-ground weapons will likely be made out of lighter materials and should be optimized for either stealth or high speed, according to Armagost. If the Air Force’s plans are realized, aircraft or drones would be expected to fly into battle carrying cheaper weapons that are able to destroy a wider range of targets.

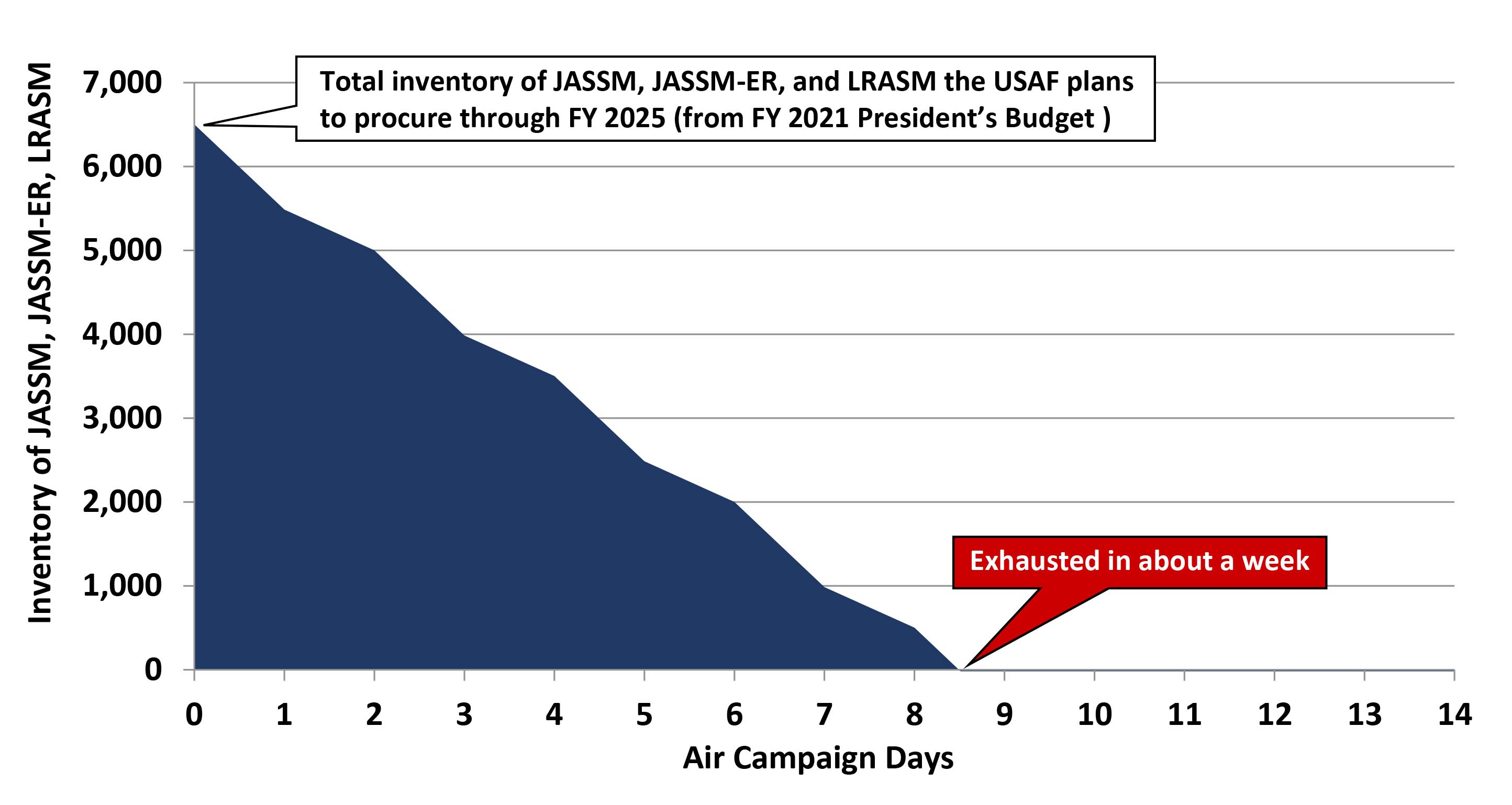

Lower costs should also mean larger munitions stockpiles, to help remove the risk of running out of weapons in a full-blown conflict. Even fighting against a low-tech enemy like ISIS, the Air Force began to experience a weapons shortfall. The problem of munitions stockpiles becoming exhausted in scenarios involving a peer or near-peer adversary is one that has concerned Air Force planners for a while. The Mitchell Policy Paper includes the following chart that shows how the Air Force could run out of standoff munitions after a little over a week of high-intensity fighting against a peer aggressor:

This challenge is compounded by the increasing ability of adversary air defense systems to shoot down individual munitions. That simple equation means that platforms will, in the future, have to carry more munitions for the same number of targets.

The exceptions to this vision of future Air Force munitions would be specialized weapons that are intended for destroying “hardened, deeply-buried” targets like enemy command bunkers, or mobile targets. The latter target set would be dealt with using long-range high-speed missiles, perhaps a reference to the various air-launched hypersonic weapons programs now under development. Bunker-busting weapons are another are of munitions on which the Air Force is already well-focused, including a new 5,000-pound-class weapon, the GBU-72/B, which is now in testing.

Not mentioned by Armagost were nuclear weapons, development of which also continues, with major programs underway to provide the Air Force with new freefall nuclear bombs and nuclear-armed cruise missiles.

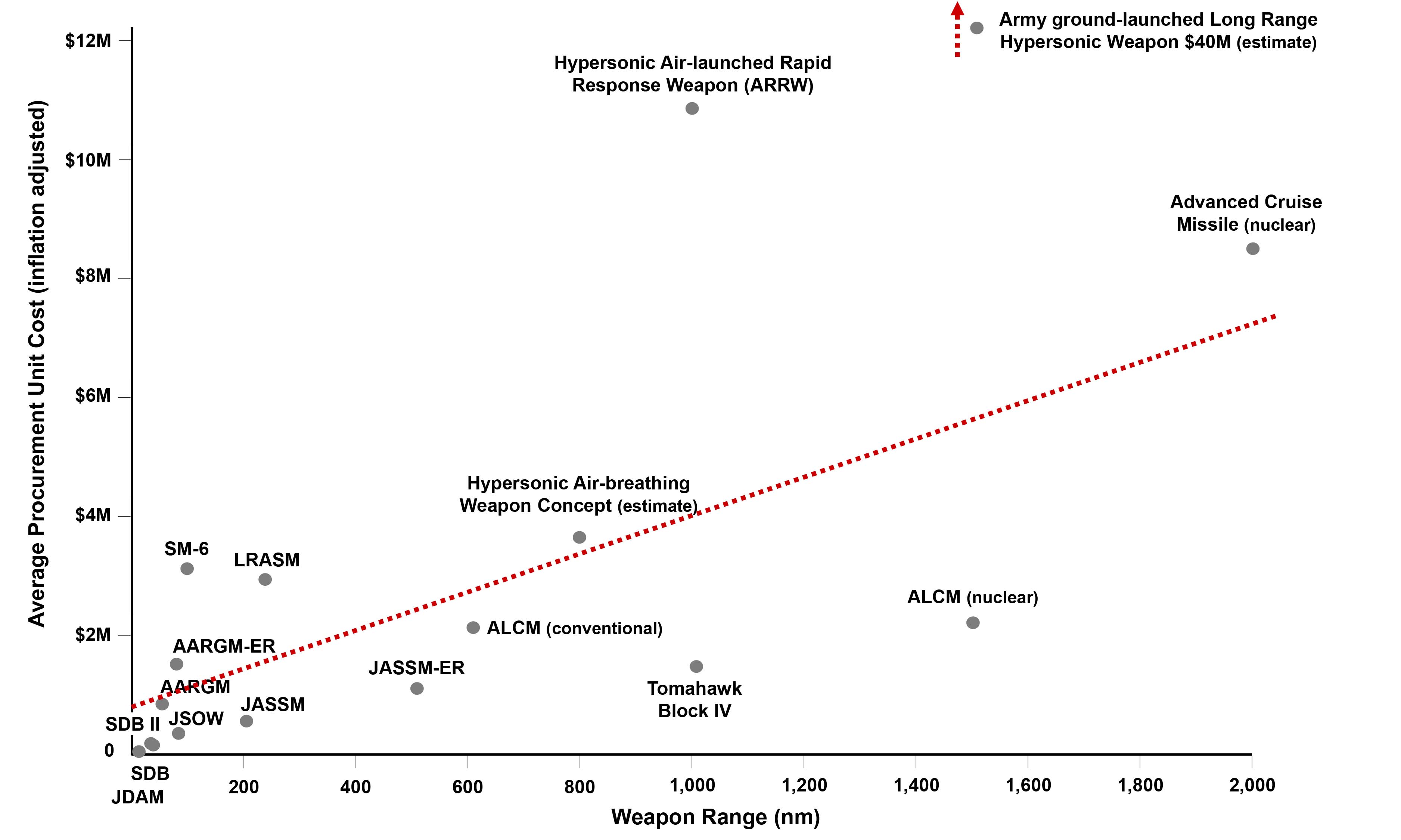

However, the promised versatility of “multi-domain” munitions should mean that these make up the bulk of the air-to-ground weapons inventory, suggesting that it might be possible to procure smaller numbers of highly expensive hypersonic weapons, as well as bunker-busters.

All this could spell the end of well-established Air Force weapons like the Joint Direct Attack Munition, or JDAM, which has frequently been the go-to choice for precision attacks in recent campaigns.

While Gunzinger’s paper argues that the Air Force should have fielded a successor to JDAM “five years ago,” Armagost talked about a “series of ongoing decisions and tradeoffs” to determine when and how to replace it and other precision munitions now in service. Part of that calculation will involve the Air Force’s developing ‘kill chain’ concept, in which a wider array of assets is potentially involved in launching strikes more quickly, at longer range, with greater accuracy, and more survivability.

“You don’t want to get into a situation where you’re having to get creative with legacy weapons that don’t really answer the mail in a high-end fight,” Armagost said.

As for the technical details or specifications of the new kinds of weapons envisaged, Armagost didn’t provide too many specifics, but he did note that one option might be to add an additional motor to existing munitions. Using a motor that is “additively manufactured” — better known as 3D printed — would be one way of achieving the required long-range, he added.

Armagost also outlined the possibility of using a “low observable, lifting-body” type design for a stealthy long-range munition. A lifting-body design is one in which the body, in this case the missile itself, produces lift, rather than relying on wings or other flying surfaces, suggesting a break from traditional “tube-and-fins” designs.

He also pointed to developments taking place in multimode seeker technology, which could perhaps see common seekers used across multiple munitions. Open-systems architecture is another factor that Armagost thinks will help achieve these ambitions, including a price tag of $300,000 or less per round. That figure compares with $186,000 for a Small Diameter Bomb II (SDB II), also known as Stormbreaker; $698,150 for an AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles, or JASSM; and $1,358,787 for a Tomahawk cruise missile.

These weapons should also be suitable for all types of Air Force platforms, fighters and bombers, fifth-generation and legacy, manned aircraft and drones, and especially long-range assets that may very likely have to respond to a fast-changing list of target locations, and even types of targets. That implies that the weapons would need to have at least some ability to be programmed for specific targets while aboard the aircraft and potentially after they have been launched.

The idea of air-launched weapons using some kind of modularity is not entirely new. In the past, the AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon, or JSOW, was developed with different modular warheads, with cluster bomb dispenser, submunitions, and unitary options, although only the latter remains in service. More recently, the Stand In Attack Weapon, or SiAW, has leveraged the modular nature of the AGM-88G Advanced Anti-Radiation Guided Missile-Extended Range, or AARGM-ER, design, which features a modular payload section.

Meanwhile, the Air Force is exploring a host of low-cost standoff munitions concepts, as well as the Golden Horde swarming munitions concept, which is being similarly driven by concerns about having the best types of munitions for specific targets.

In a future scenario, the kind of technology outlined by Armagost for air-launched munitions could also become more achievable thanks to the advantages offered by networking weapons. These include the technologies pursued under the Pentagon’s emerging Joint All-Domain Command and Control architecture, or JADC2, which aims to connect sensors from all U.S. military services into a single network. Among the advantages of networked weapons are the ability to be dynamically retargeted, to use offboard sensors for targeting throughout their flight, and even operate in swarms to enhance effectiveness and survivability.

Then there is the growing activity relating to air-launched missile-toting drones, like in the LongShot program and the Flying Missile Rail concept. While these envisage an air-to-air combat drone, rather than an air-to-ground solution, they are similarly intended to extend the range of the launch platform and reduce its vulnerability to hostile aircraft or air defenses, among other benefits.

According to Armagost, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall is already on board with his ideas and, in response, has agreed to buy fewer legacy weapons and instead invest in the development of new ones that are more flexible and cheaper.

Currently, the Air Force is involved in major efforts to field new-generation combat airpower, including an eventual successor to the F-22 air dominance fighter and the new B-21 stealth bomber. At the same time, it’s embarking on programs to provide these aircraft, and others, with hypersonic weapons, a nuclear-tipped cruise missile, and other advanced munitions. Now, it’s also tackling the challenge of how to supersede the JDAM and other less glamorous munitions, increasing air-to-ground effectiveness while ensuring that such weapons are available in the kinds of numbers that would be required in future combat scenarios.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com