Polish state-owned defense contractor Mesko offers, or at least offered, a system designed to prevent unauthorized use of its Grom shoulder-fired heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles, according to a recently released report. This would appear to be the first confirmed instance of an end-use control system being fitted to a weapon of this kind, also known as man-portable air-defense systems, or MANPADS, despite public discussion about the potential to do so for decades now. There have long been fears about what terrorists and criminals might do if they could get ahold of these weapons.

This piece of information was tucked away in a footnote in a report that Conflict Armament Research (CAR), an independent group focused on investigating arms trafficking in conflicts around the world, released last week. The document is the product of a three-year-long investigation into the flow of weapons to Russian-backed groups in eastern Ukraine’s Donbass region. The government in Kyiv has been fighting Kremlin-supported forces in this part of the country since 2014, a conflict that erupted after Moscow illegally seized Ukraine’s Crimea region that year.

A pair of Grom launch tubes and a grip stock for this weapon were among the items that CAR was able to document in Ukraine as part of its investigation. These items were reportedly recovered after a battle in the Donbass between 2014 and 2015.

A complete Grom MANPADS, a design derived from the Soviet-era 9K38 Igla, consists of a launch tube attached to a reusable grip stock assembly. The launch tube contains the actual missile and a battery coolant unit must also be attached before the weapon can be fired. One of the two tubes recovered in Ukraine had the battle coolant unit, but no missile, while the other had a missile and no battery coolant unit.

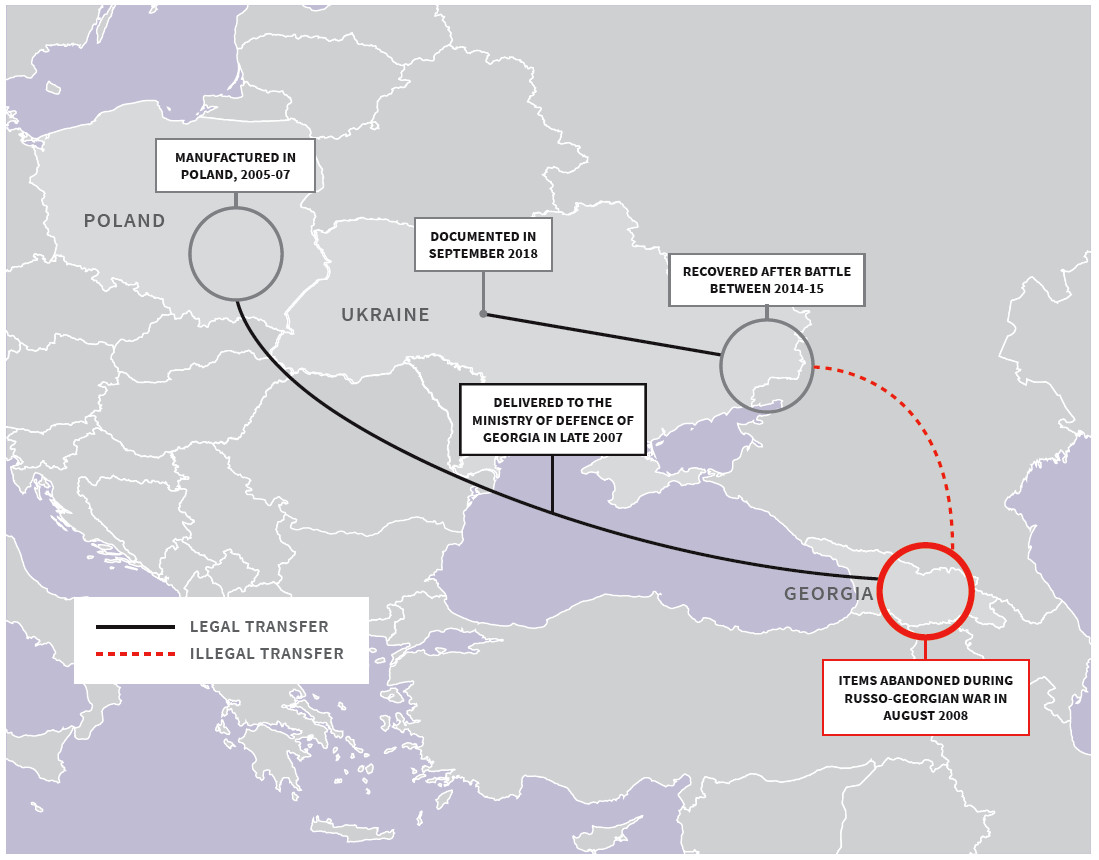

CAR was able to confirm with the Polish government that these particular tubes and the grip stock were part of an approved shipment of Grom MANPADS to Georgia in 2007. The Georgian government confirmed this and also told this independent group that there had been no approval to export any of these components to a third party. How exactly they made their way from Georgia to Ukraine is less clear, but the most logical pathway, as depicted in the map below, would be via the Russian military, which may have captured some Groms during the Russo-Georgia War in 2008. The Ukrainian government has never acquired Groms for its own military or other security forces, so it would be impossible to source them locally.

“The Polish authorities added that during the Russo-Georgian war of August 2008, many of the missiles, which had been shipped with the launchers, were used in battle and that at least 26 missiles remained in the possession of the Georgian army,” according to the CAR report. “However, some were abandoned on the battlefield and Russian forces may have appropriated them.”

“In addition, the Government of the Republic of Poland confirmed that GROM MANPADS are equipped with individual starting codes to prevent their use by unauthorized users,” the aforementioned footnote adds.

It’s not clear how exactly this system works beyond the need to input a specific code to get the weapon to function. There are no immediate details on the tubes or grip stock that CAR examined in Ukraine that would offer any clues. The fact that Ukrainian authorities recovered one launch tube in the Donbass in what appears to have been in an expended state, with no missile and the battery coolant unit fitted, would raise questions about how easy it might be to bypass these end-use controls.

This is, of course, not the first time that such an end-use control system for MANPADS has at least been suggested. The U.S. government, among others, has had concerns about weapons of this type proliferating for decades now. Since these kinds of missiles are relatively easy to transport and use, the fear has long been that they could just as easily be employed to try to shoot down commercial airliners in a domestic context as warplanes on the battlefield.

Starting in the 1980s, the Central Intelligence Agency supplied Stinger missiles to Afghan rebels fighting the Soviet Union. After that conflict ended, American authorities embarked on an expensive and complex effort to buy back any missiles that hadn’t been fired. As of 2005, American officials were still trying to recover some of these weapons. The U.S. government has sought to secure loose MANPADS in other conflicts to prevent their proliferation since then and this was one of the missions being run out of the CIA annex in Benghazi, Libya, at the time of the infamous terrorist attack on the nearby U.S. consulate in 2012.

An actual physical system that prevents unauthorized use to begin with would be an attractive alternative. In 2019, Dutch researcher Jos Wetzels presented evidence, seen in the video below, that the CIA itself explored at least one such end-use control system that would prevent a MANPADS from being employed outside of a given area and/or time frame. Similar reports had emerged three years earlier about the potential use of “geofencing” via GPS to limit where MANPADS could be fired, as well as a hard lockout of some kind set to a timer. It remains unclear whether any of this technology was ever implemented.

Matt Schroeder, a Senior Researcher at Small Arms Survey, another independent organization that investigates the supply and use of small arms and light weapons in international conflicts, who done extensive research into MANPADS and their proliferation wrote on Twitter last week that he was aware of another end-use system for MANPADS that functioned in a similar way to U.S. Permissive Action Links (PAL) on nuclear weapons. Again, it’s not clear if that specific technology has actually been put into use.

These are not the only novel export controls that the U.S. government is rumored to have developed and implemented. There have long been reports that Pakistani F-16 fighter jets are fitted with systems that would allow American officials to remotely ground them, or at least disable some of their capabilities, should the need arise.

Even before this confirmation that some kind of coded lock was added to the Groms sold to Georgia, there had been reports that Poland had been using this technology on other weapons.

“There were reports that Polish manufacturers developed control technology for the Piorun,” Schroeder told The War Zone directly, referring to another more modern Polish MANPADS also known as the Grom-M. “However, the installation of control technology in the Groms exported to Georgia in 2007 is much earlier and, assuming these reports are true, means that Poland has more than a decade of experience with use control technology in exported MANPADS. Hopefully, the lessons learned through Poland’s experience will facilitate the development and installation of use control technologies by MANPADS manufacturers in other countries.”

The Polish implementation of an end-use control system on Grom as early as 2007 certainly raises the possibility that other companies or thirty parties, such as the CIA, have put similar technology into use already. The confirmation that an end-use control system is or at least was available for Grom in 2007 certainly lends additional weight to reports that a similar system was developed for Piorun, which is seen in Polish use in the video below.

This wouldn’t just apply to MANPADS, either. There has been similar discussion over the years about implementing these kinds of controls on other kinds of weapons, especially other man-portable missiles, including anti-tank guided missiles. There have been particular proliferation concerns about what might happen to TOW anti-tank missiles supplied to Syrian rebels by the U.S. government. The CIA reportedly required groups in Syria to provide video evidence of actually having fired missiles before they could receive new ones as one end-use control mechanism.

Still, putting the kind of technology that Mesko developed for use on Grom into MANPADS, more generally, is of particular importance, according to Schroeder.

“The installation of use control technology on exported MANPADS is a critically important supplement to other control measures,” he told The War Zone. “Rigorous export controls and stockpile security measures are necessary but no control regime is perfect and the theft, loss, or diversion of even a single functional MANPADS could have dire implications of regional aviation security. Assuming it functions as intended (and cannot be spoofed or disabled), use control technology provides a last layer of defense against unauthorized end-use.”

It will definitely be interesting to see whether more information about the installation of end-use control systems on MANPADS or other man-portable missiles emerges now that Polish authorities have publicly confirmed doing so on at least one occasion nearly 15 years ago.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com