A mocked-up U.S. Navy aircraft carrier and other warships from its battle group, as well as at least one simulated vessel that can move on rails across the desert in northwest China, are among the latest tools to help the People’s Liberation Army refine its anti-ship capabilities. While we have seen static warship replicas used in this way before by the PLA, the giant moving target is a new development and reflects the seriousness with which Beijing views its anti-surface warfare capabilities, which notably include anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) launched from the land and by aircraft, as well a range of advanced cruise missiles. Hypersonic anti-ship missiles could even be on the horizon, as well.

Satellite images revealing the new static and mobile targets were published yesterday by USNI News. You can and should check out all the imagery and complete analysis from H. I. Sutton and Sam LaGrone here. The images from satellite imagery company Maxar show the training targets on what appears to be a newly expanded range complex in the Taklamakan Desert in southwest Xinjiang province.

This is an area that has been used in the past for Chinese ballistic missile tests, including ASBMs, although the purpose of these life-size warship models may well also encompass trials of PLA electronic warfare systems and kinetic weapons.

Aside from an aircraft carrier mockup, which was reportedly installed in early 2019 before being dismantled and then reinstated in September of this year, the group of targets also includes at least two Arleigh Burke class guided-missile destroyers, which would typically escort a flattop as part of its battle group. However, the most intriguing feature is the new rail-based testing aid, which makes use of a 20-foot-wide rail system onto which a specialized surrogate warship can be mounted and then used as a moving target, presumably mimicking different adversary vessels and their equipment as required.

Satellite imagery from this month shows the carrier target some 12 miles south of the main storage site at the facility, while the railway appears to extend beyond this point by roughly the same distance again, suggesting a considerable construction effort. Compared to static targets, this approach clearly offers a much greater degree of realism, with the ability to practice engaging a simulated vessel while it’s underway.

The same kind of mobile target appeared in model form at the Zhuhai Airshow in September this year, as part of a display of different target simulation systems. The images of the model provide a better look at some of the details of its features, including the various vertical antennas. The China Aerospace Science & Industry Corporation (CASIC) developed the moving ship target, which was was described as “a land-based system for mimicking Blue Army electronic warfare threats.” It would seem likely this could work both ways — as a training aid to test counter-countermeasures for enemy ships on offensive operations, but also potentially to test Chinese countermeasures against incoming threats.

Interestingly, we know the U.S. Navy rapidly deployed at least one electronic warfare system specifically due to threats emanating from China and that it has fielded other similar systems based on other regional threats, which seem to at least include various kinds of anti-ship cruise missiles. The latter threat is also particularly relevant when it comes to the PLA. Another system, deployed aboard carriers in the Pacific, is also likely a response to peer adversaries evolving anti-ship capabilities in the region.

Being able to replicate these enemy capabilities and test them against anti-ship weapons and sensors in the PLA’s inventory in a realistic manner, all while being far from prying electronic surveillance sensors, is a highly relevant capability to possess.

It’s also possible that these targets are intended, initially at least, to examine target acquisition rather than end-to-end missile tests, which would end in their destruction. According to geospatial intelligence company AllSource Analysis, which originally identified the new site, there is so far no evidence of weapon impacts around the targets. Of course, that could change in the future. Other replica ship ‘sleds’ could be built to be destroyed, too. This would allow for end-to-end tests against a moving target, which would be highly valuable to the PLA.

As for the static targets, these appear to be highly realistic, with a much-improved level of fidelity over previous ones. The level of accuracy is impressive, with the destroyers, for example, featuring not only the helipad and bridge superstructure but also individual funnels and vertical launch systems (VLS). On the other hand, the carrier target appears to be essentially flat, with various details including the island and aircraft elevators missing.

Nevertheless, it’s more detailed compared to images we’ve seen in the past of a cruder Chinese aircraft-carrier-sized static target. The target seen below, installed in the Gobi Desert’s Shuangchengzi missile test range, has been noted surrounded by multiple craters from large missile impacts.

The appearance of these new types of targets is especially notable at this point, with China widely believed to be refining its burgeoning ASBM capabilities. So far, there have been several tests in which missiles have been launched against targets at sea, but Western analysts consider that these technologies are yet to be perfected.

By continuing critical parts of the ASBM test program out in the desert, China’s efforts in this direction will be better hidden from foreign intelligence and would also increase the options for telemetry and other means of monitoring the accuracy of these weapons as part of a fully instrumented test range. Furthermore, tests at sea involve closing off extensive areas of water to maritime traffic, alerting observers to potential missile trials as well as giving an indication of the overall capabilities of these weapons. In the past, the U.S. military has kept a close eye on ASBM tests, among others.

It’s also a fact that it can be hard to conduct full-range testing at sea. The United States has the benefit of expansive ranges at the other end of the Pacific, with no need for overflights of other national territories when launching missiles from California or Alaska, for example. The waters surrounding China are far busier by comparison.

China’s growing ability to target aircraft carriers as well as other surface combatants with ASBMs is, of course, an area of particular concern for U.S. officials.

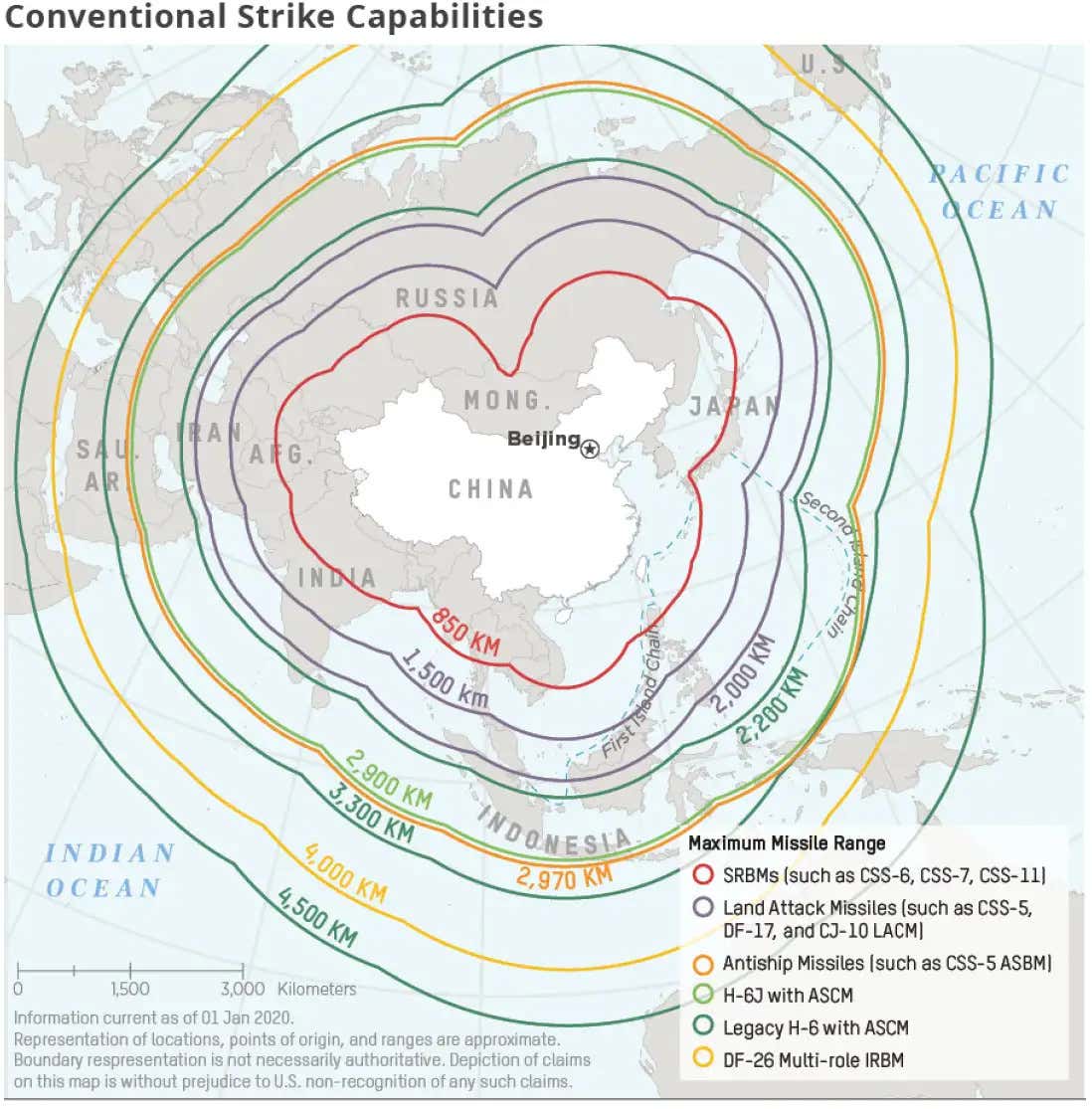

In its annual report to Congress on the status of China’s military capabilities, the Pentagon attributes the conventionally armed DF-21D (also known by the Western designation CSS-5 Mod 5) ASBM variant with the ability to “conduct long-range precision strikes against ships, including aircraft carriers, out to the Western Pacific from mainland China.”

The DF-21D system is understood to have a range of more than 930 miles, a maneuverable reentry vehicle (MaRV), and the ability to rapidly reload its launchers in the field.

“The PLA has fielded DF-21D ASBMs specifically designed to hold adversary aircraft carriers at risk when located within 1,500 km of China’s coast,” the report explains.

Although not acknowledged by Beijing, the first confirmed live-fire test for the DF-21D in July 2019 involved six examples of the missile being fired into the South China Sea, north of the Spratly Islands.

In addition, the longer-range DF-26 (CSS-18) intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) fielded in 2016 is also available in an ASBM variant and is thought able to strike targets at a distance of almost 2,500 miles.

“The multi-role DF-26 is designed to rapidly swap conventional and nuclear warheads and is capable of conducting precision land-attack and anti-ship strikes in the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the South China Sea from mainland China,” the Pentagon report adds.

In August 2020, single examples of the DF-21D and DF-26 reportedly struck a moving target vessel sailing near the Paracel Island chain, in the PLA’s first known demonstration of an actual long-range ASBM capability. Furthermore, the PLA also has short-range anti-ship ballistic missiles which they also need to test, designs, which you can read more about here.

As well as these “carrier-killer” missiles delivered from road-mobile transport-erector-launchers (TELs), the PLA is also working on an air-launched ASBM program, with the so-called CH-AS-X-13 having been noted carried underneath the People’s Liberation Army Navy Air Force H-6N missile-carrier.

Overall, whatever their delivery platform, ASBMs provide a powerful new variable in the maritime battlespace. Being able to maneuver dynamically during reentry and flying at hypersonic speeds and steep angles of descent, these types of missiles are immune to all but the highest-performance defensive weaponry, and even that is questionable. Providing the ASBMs work as advertised, in a time of crisis they could push U.S. carrier strike groups far enough from Chinese shores to make their strike fighters and cruise missiles useless. In this way, ASBMs are a cornerstone of China’s anti-access/area-denial maritime strategy.

Elaborate targets mocked up as U.S. Navy warships are a stark reminder of the tensions between Beijing and Washington, including over the question of the status of Taiwan and Chinese claims over the South China Sea. Beyond that, the targets signal once again the fact that anti-carrier capabilities are a central component of the PLA’s doctrines, with considerable resources being plowed into ASBMs in particular.

Without a doubt, Beijing is expending significant effort into fine-tuning the effectiveness and reliability of these and other naval warfare capabilities, which is bad news for the U.S. Navy and its allies.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com