The U.S. Navy says it plans to begin converting the first of its Zumwalt class destroyers to fire the service’s future Intermediate-Range Conventional Prompt Strike hypersonic weapons, or IRCPS, in the 2024 Fiscal Year. The launchers for these missiles, which will be loaded onto the ship’s inside triple-packed Advanced Payload Module canisters, will replace the 155mm Advanced Gun Systems on these stealthy destroyers. The Navy decided back in 2016 not to buy any ammunition for those guns due to ballooning costs, rendering them effectively dead weight and prompting discussions about the possibility of installing other weapons in their place.

Naval News

first reported this new schedule information. The Navy’s budget request for the 2022 Fiscal Year, released earlier this year, had already revealed that the service hopes to have some level of operational capability to launch IRCPS missiles from its Zumwalt class ships by the end of 2025. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Mike Gilday had previously confirmed the basic plan for adding hypersonic missiles to these destroyers, which are also referred to as DDG-1000s after the hull number of the lead ship, USS Zumwalt, during a talk at an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments think tank in April. The Navy is planning to integrate IRCPS onto its future Block V Virginia class submarines, likely using the Advanced Payload Module (APM) canisters, as well, and the weapon could find its way onto other vessels.

“The DDG-1000 Dry-Docking Selected Restricted Availability (DSRA) will begin in FY 2024,” Lieutenant Lewis Aldridge, a spokesperson for the Navy’s Office of the Chief of Information, told Naval News. “The Navy began engineering planning efforts to accommodate integration of CPS on Zumwalt-class destroyers, which includes removal of advanced gun system mounts and installation of Advanced Payload Module (APM) launcher technology.”

The Navy has commissioned two Zumwalt class destroyers in service, the USS Zumwalt and the USS Michael Monsoor. The third ship in the class, the future USS Lyndon B. Johnson, is still in the process of being fitted out.

Lieutenant Aldridge said that the IRCPS launch systems would only occupy spaces previously occupied by the Advanced Gun Systems (AGS) and that there are no plans to add any additional vertical launch system (VLS) cells to the Zumwalt class destroyers. The DDG 1000s each have 80 Mk 57 VLS launch cells. At present, these cells are expected to be loaded with a mix of SM-2 Block IIIAZ and Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) surface-to-air missiles, the latter of which can be quad-packed into a single cell, as well as Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles. Of course, other types of missiles, such as variants of the ever-more-capable SM-6 family, could be added to the destroyers’ arsenals in the future, as well.

The Navy did not confirm to Naval News how many IRCPS missiles the converted stealth destroyers will be able to carry at once, though it has been reported that up to 12 of these weapons could be loaded onto each ship in the future. This would mean two APMs would take the place of each of the AGS turrets. This may seem like a limited number, but each one of these missiles will reportedly be some 34 and a half inches in diameter and could be 30 feet or more in length. By comparison, a Tomahawk has a length of some 20 and a half feet, including a rocket booster necessary to fire it from a VLS cell, and less than 20 and a half inches in diameter.

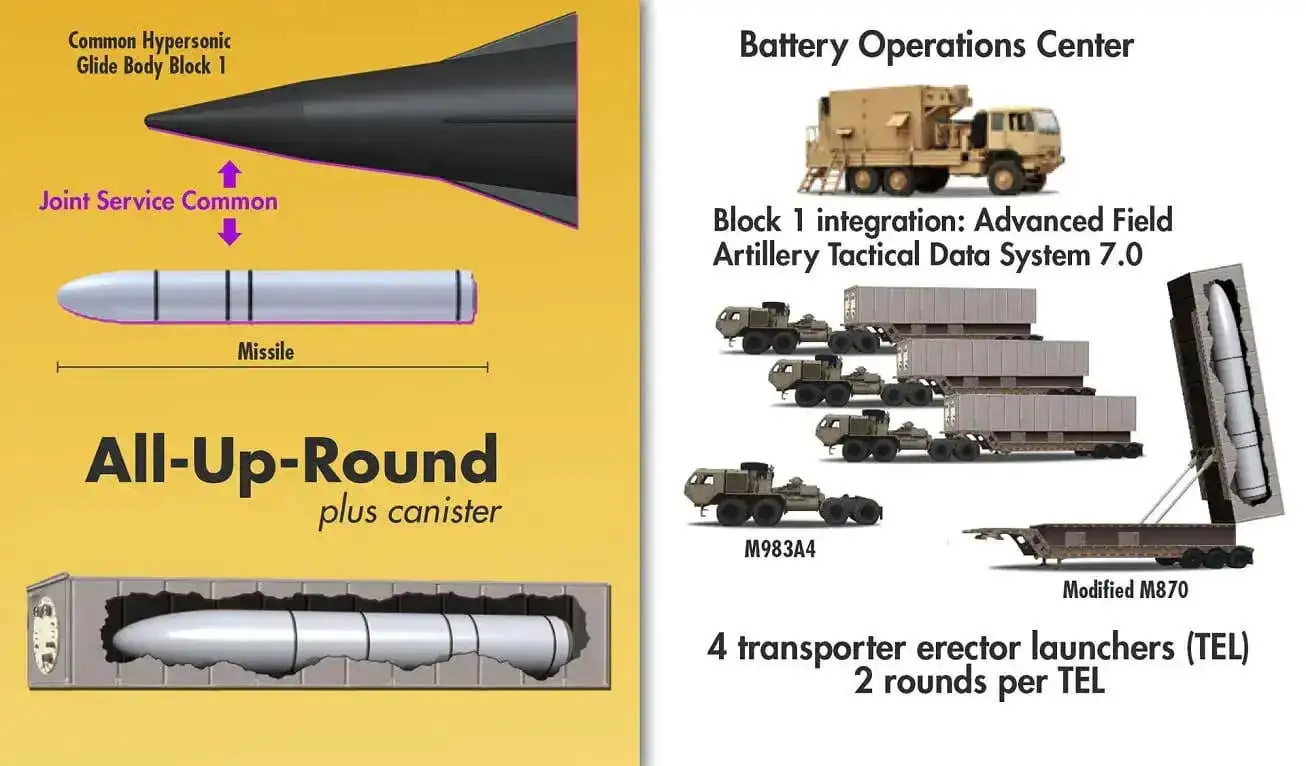

IRCPS’ expected dimensions are based on what is known about the U.S. Army’s ground-based Dark Eagle Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) system. Dark Eagle and IRCPS are using the same missile design, with a common unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle on top, with how they are launched being the only difference between the two.

These missiles, like other designs using hypersonic boost-glide vehicles, use rocket boosters to get their payload to a desired speed and altitude. Once there, the vehicle separates from the rest of the weapon and glides back down toward its target, flying along an atmospheric trajectory at a hypersonic speed, typically defined as anything above Mach 5.

Boost-glide vehicles are also designed to be highly maneuverable, allowing for more unpredictable movements over the course of their flight compared to typical ballistic missiles, even those with advanced maneuverable reentry vehicles. This presents significant challenges for opponents in terms of detecting the incoming weapon and responding to it, including any attempts to intercept the threat. Giving an enemy less time to react also reduces their ability to relocate critical assets or just seek cover. All of this, in turn, means hypersonic weapons present an ideal choice for penetrating through even the densest air and missile defenses to strike high-value and potentially time-sensitive targets.

The DDG-1000s are the most advanced and survivable surface combatants the Navy has available to it now, despite years of watering down of their capabilities, including by adding external systems that increase their radar signature. Integrating IRCPS onto these destroyers could open up new missions for them, either while operating independently or as part of larger surface actions groups. Their stealthy qualities, in particular, would improve their ability to get within range of their targets, even ones relatively deep inside enemy territory, even just to hold them at risk as a deterrent during a major crisis.

At the same time, questions have repeatedly been raised about the exact operational utility of a class of three ships. At present, the Lyndon B. Johnson, which left port for its first sea trials in August, isn’t even expected to be commissioned until 2023. All three examples are expected to be assigned to a developmental unit, Surface Developmental Squadron One, though the Navy insists that they will make regular operational deployments.

The Navy originally planned to buy 32 DDG-1000s, but scaled that order back multiple times before settling on purchasing a trio of these destroyers. This had the knock-on effect of sending the unit cost for each one of these ships skyrocketing, from the original estimated price tag of $1.3 billion in 1998 to more than $9 billion by September 2020, according to the Government Accountability Office. It’s not clear how much refitting the Zumwalt class vessels to fire IRCPS, or other potential upgrades, such as new radars, might add to this price point.

The decision to add only a relatively limited number of IRCPS missiles, which would be intended for use against very high-value targets, rather than more traditional VLS cells to the DDG-1000s, could add to an ongoing debate about the Navy’s overall conventional missile-launching capacity. It has been noted that the service’s fleet structure plans, which remain in flux, generally involve retiring ships and submarines with significant numbers of VLS cells.

This is particularly true of the Navy’s desire to divest a significant portion of its Ticonderoga class cruisers and the expected retirement of the four Ohio class guided-missile submarines. The service has said it plans to acquire new large surface warships and so-called “large payload submarines,” as well as a fleet of large-displacement unmanned surface vessels (USV), which could have their own missile magazines. However, any new classes of large surface combatants or missile-carrying submarines are still years away from becoming a reality and Congress has expressed skepticism about plans for large USVs.

There has also been some discussion about the potential for increasing the missile-carrying capacity of the Navy’s future Constellation class frigates. Before it selected a design, the service did change its requirements for those ships, increasing the number of VLS cells each one had to have from 16 to 32.

In 2019, the Navy said it could add between $16 and $24 million to each one, and potentially cause delays in delivery, to add another 16 VLS cells to any of the competing designs. As The War Zone has reported, the Constellation class design the service eventually selected is longer, wider, and displaces substantially more than the ship it was based on, the Italian subvariant of the Fregata Europea Multi-Missione (FREMM), or European Multi-Mission Frigate. This is in part to allow for “future growth,” which might raise a possibility that space has been built in to allow for the addition of new missile-launching capacity as time goes on. At the same time, the Navy has talked about adding other capabilities to these ships, including directed energy weapons.

“For the Navy, we know that’s a distributed maritime operations concept that is driving a smaller, more distributed fleet [with fewer] large vessels, and more lethal, smaller vessel. That means frigates. So we should have that debate over whether we should put that next dollar into a 33-year-old cruiser, or whether we should invest in the Flight III [Arleigh Burke class] DDG,” Chief of Naval Operations Gilday said back in April. “We can’t just be counting VLS tubes and satisfying ourselves that that’s the sole metric we’re going to look at.”

The Navy has clearly decided that arming its DDG-1000s with IRCPS missiles in the coming years is an important part of that overall plan to increase the lethality of its fleets.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com