Much ado has been made over the F-35’s Automated Logistics Information System (ALIS) backend cyber support infrastructure. It’s supposed to do everything from controlling the F-35’s worldwide parts supply chain to mission planning and debriefing. This system, among the F-35’s most troubled components, could be viewed as the jet’s cyberspace Achilles’ heel. Alternatively, it could be a huge asset, when you consider the potential it holds for electronic intelligence gathering on an unprecedented scale.

When it comes to aerial combat, mission planning is as vital to success as executing the mission itself. For stealthy aircraft weaving their way between enemy radar installations, planning is even more crucial with a “Blue Line” route being carefully devised to make the most of the jet’s low-observable features. To build this path, up-to-date intelligence on the enemy’s electronic order of battle is needed, essentially a detailed map of their air defense system with enemy weapons engagement envelopes extrapolated over the top. This data is classically collected by strategic assets, but the F-35 fleet itself may become the most prolific purveyor of this critical information.

One of the central features that makes the F-35 survivable even against high-threat enemies is its ability to suck up electronic signals from radars and air defense nodes, and to quickly classify them, geolocation them, and display them for the aircraft’s pilot. This capability makes that traditionally fixed “Blue Line” a flexible one during combat. With F-35 users’ mission information being loaded into ALIS then downloaded after every sortie, the electronic intelligence the jet soaks up during its time in the air could be mined and exploited by the U.S., as well as partner nations, to some degree.

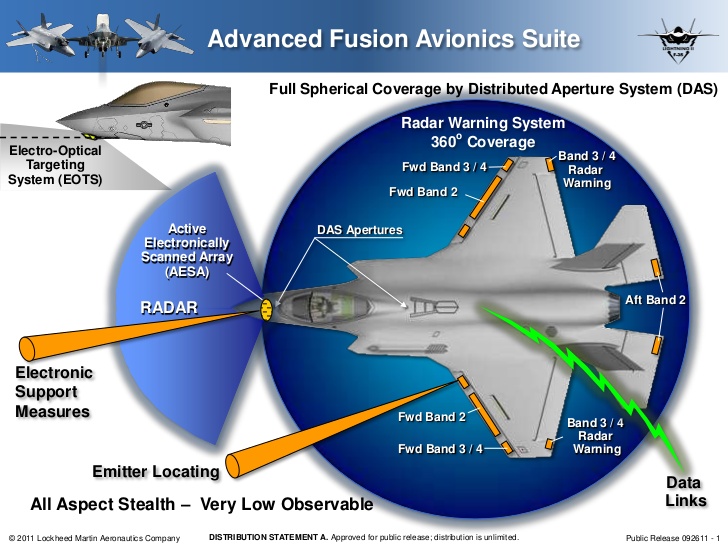

The F-35 gathers this info via a series of passive antennas embedded in the F-35’s edges that feed signals information to the jet’s computers. Using interferometry, the slight time delay between when a signal hits one antenna compared to another, azimuth and range can be defined and target-quality coordinates on where the threatening radio frequency emission is coming from can be devised. This system is known as the F-35’s Radar Warning Receiver (RWR) and Electronic Support Measures (ESM) suites. These are tied into a broader set of features that also make up the jet’s electronic warfare capabilities.

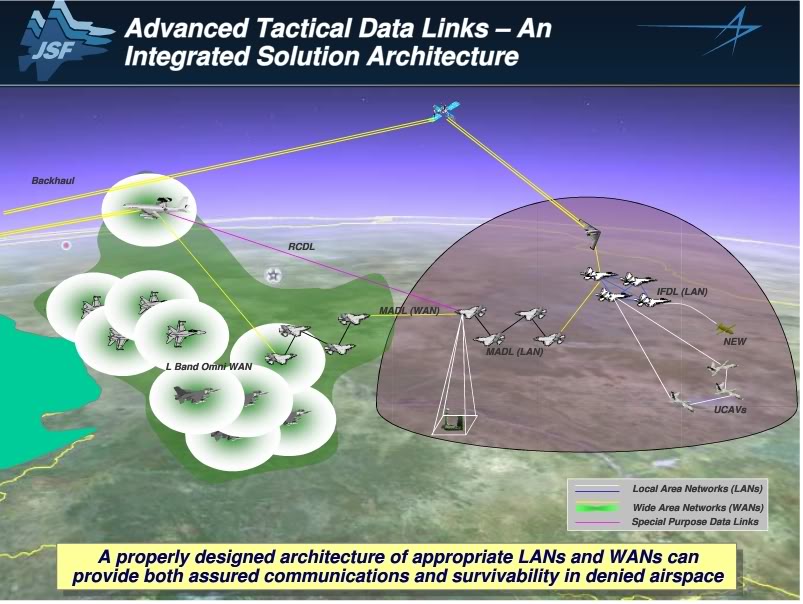

A group of F-35s can share this information seamlessly via their daisy chain-like directional, low-probability of intercept proprietary Multi-Function Data-Link (MADL). The Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) that the F-35 soaks up allows F-35 pilots to see these “threat rings” in real time and they can choose to avoid, engage, or electronically attack the source of those threat rings depending on where they and their fellow F-35s are located and what their mission is at hand.

The F-35 is not the only fighter-sized intelligence “sponge” around. Far from it, in fact. When it comes to fighters, the F-22’s ALR-94 Electronic Service Measures (ESM) suite is also capable of collecting and displaying this information, as are aircraft like the Eurofighter Typhoon, or the F-16CG to a certain extent. The difference is that the F-35 represents the latest iteration of this capability and will be operated all over the world by various air forces simultaneously, all dumping huge amounts of data into ALIS.

The F-35’s high level of electronic battlefield situational awareness, paired with ALIS, could theoretically build a worldwide battle database organically, one that is god-like in its breadth and timeliness. Although this may be a latent capability now, reconnaissance has always been a mission element of the F-35 program, and Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) collection could rapidly become much more of a primary mission for the F-35 as the program, and ALIS, evolves.

F-35s around the globe could be employed as mini-RC-135 Rivet Joints during peace time, prowling near (or perhaps in) enemy territory and classifying, recording, and geolocating all types of radar and integrated air defense communications signals and positions. All this information can then be uploaded into ALIS’s master memory bank. Think of it as “distributed” electronic surveillance, whereby individual nations can use their F-35s to fly reconnaissance missions regularly, adding to the electronic order of battle “picture” worldwide in near real time.

Such a strategy would disperse the ELINT capture mission from a traditional platform specific strategy — where lumbering aircraft like RC-135 Rivet Joints, EP-3E Aeries RQ-4 Global Hawk, U-2 Dragon Lady and P-8 Poseidons are heavily tasked with trying to keep tabs on potential enemy defenses — to one that leverages the F-35’s wide distribution around the globe. One that can alleviate demand on these strategic assets via the constant regional collection of tactical intelligence of a similar nature.

Taking pressure off these low-density/high-demand strategic electronic intelligence collecting assets, only owned by a handful of nations, will allow them to focus on key hotspots, some of which are only easily accessed by long-range aircraft. They can also continue to provide unique and very high-end surveillance that the F-35 cannot.

This functionality also lends merit to ship-borne F-35 operating concepts, especially the F-35B, deployable on smaller amphibious aircraft carriers which are accessible financially to F-35 customer nations. The massive leap in capabilities the F-35B offers America’s “Gator Navy” is already known. Being able to position the F-35B off the coast of a potential foe allows the jet to collect ELINT without being heavily restricted by its tactical fighter-sized endurance or relying on expensive and complex tanker support.

Additionally, forward deploying the F-35B to small islands with runways adapted for F-35B operations advances the jet’s ELINT reach without the need for a carrier. Even the F-35’s stealth capabilities are enticing for the ELINT mission. In stealth mode, it can provide surveillance on the enemy’s electronic order of battle when their integrated air defense system is at rest. It can fly that same mission again with radar reflectors attached, stimulating a working air defense network and tracking how it reacts to a “visitor,” noting weak spots and vulnerabilities in coverage. An RC-135 or RQ-4 cannot do this.

The ELINT data F-35s collect could be processed centrally and parts of it made available to certain users, either regionally or nationally. This is adventageous because having an up-to-date electronic order of battle on a wide array of potential threats over vast geographical distances has always been an expensive and challenging task. A worldwide F-35 force could change this reality and give the F-35 a more prominent peacetime reconnaissance mission. It would allow far greater coverage capacity than what dedicated SIGINT/ELINT aircraft can provide today. In particular, it would vastly expand the Pentagon’s Signals Intelligence and Electronic Intelligence spying umbrella in an organic nature, at little cost.

It’s still unknown exactly how ALIS will process all this data, and who will have access to it, but it’s possible to envision alliances like NATO countries having access to their own ALIS backend of air defense threats in their region. Missions could be flown by F-35s for just the purposes of keeping the database current. The transfer of the F-35 data post-mission, th uploading to the ALIS cloud, and exactly who gets to exploit which parts of that data is already an issue. On the very topic of that conundrum, USAF Colonel Max Marosko, deputy director of air and cyberspace operations for Pacific Air Forces, told Flightglobal.com:

“Given an example of Brit F-35s in one lane and US F35s in another lane, if our databases aren’t synchronized, you’re going to end up with conflicting identification using, which could delay employment and put the force at more risk… We can ensure we’re all on the same playing field and we don’t have any identification problems that could most likely lead to a lack of shooting and putting the pilots at more risk. That’s an important thing to consider.”

Yet using ALIS to capture intelligence during times of peace, to prepare for possible times of war seems also highly relevant. This is especially true for potential peer-state conflicts that could encompass large portions of continents, not just those involving small third-world countries.

It’ll be interesting to see ALIS evolve and the myriad of ways its heaps of data can be leveraged in the future. The biggest question is whether it will be done transparently or clandestinely? Yes, enemy air defense capabilities could be monitored on a grand scale, but so could the tactics and capabilities of actual F-35 operators and anyone they train with. Theoretically, that information will all be dumped into ALIS’s big brain after every mission.

Israel, for example, has opted to employ their F-35s without a high-degree of dependence on ALIS. Time will tell if this will be standard operating procedure or merely a fallback should ALIS’s security be breached, something that is a real possibility. Israel, who holds its air combat playbook very close to its chest, may see using ALIS as risking to much to foreign eyes, even if those eyes are friendly.

Israel’s F-35s themselves will be loaded with Israeli specific combat systems that will diverge from the F-35A’s baseline configuration and capabilities. Showing the capabilities of these indigenous modifications, what they can detect and how they can neutralize electronic threats, may expose more than the IAF wants. Even data detailing how Israel operates existing fighters alongside the F-35 could be a liability. As such, ALIS may either run in a tailored nature for the IAF, or none at all.

And therein lies the double-edged sword that is ALIS. While it can greatly enhance F-35 operations, the information it collects could be processed into a potent weapon of its own. On the flip side, the more a force relies on it, the less operational sovereignty and confidentiality they will have. Still, the F-35 acting as a conduit for a global ELINT and other air combat-related intelligence network is incredibly enticing. For individuals with access to that information, it would make the F-35 program, and the jet itself, more valuable than what’s offered at face value.

That is not to say a similar system could not be applied (or may already be applied) to high-end unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) and a common operating system that controls and supports them. The primary “eyes” of these autonomous unmanned aircraft are the electronic environment around them, and their ability to act as a collective swarm hinges on the quality of this real-time ELINT data. When not waging war, they would be more inclined to provide reconnaissance using their innate abilities to detect the enemy’s electronic order of battle and their superior endurance when compared to manned fighters.

For better or worse, while the U.S. is not selling a multinational, UCAV program, they are selling the F-35. That is not to say that one day ALIS’s potentially panoptic electronic order of battle data collection capabilities could not be leveraged by a UCAV swarm’s hive mind. It is also possible that the reverse could be true and the F-35 could benefit from the UCAV’s dynamic threat picture. Lockheed could very well adapt ALIS, or at least portions of it, for the unmanned realm of aerial warfare. In fact, such a plan is likely already be in the works now.

Contact the author tyler@thedrive.com