A senior officer at the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command, or NORAD, says the command is actively engaged in discussions about how to optimize air-defense capabilities, including ground-based surface-to-air missiles, to protect domestic critical infrastructure in a crisis. He said that the growing ability of potential adversaries to launch long-range conventional strikes, especially using advanced air, sea, and submarine-launched cruise missiles, has prompted new concerns about threats to the homeland, which is “not a sanctuary any longer.” This is just the latest example of U.S. officials sounding similar alarms bells in recent years — but it is a less common public acknowledgment about the limitations of existing defenses within the continental United States.

U.S. Air Force Colonel Kristopher Struve, the vice director of operations for NORAD, discussed domestic critical infrastructure defense during a virtual roundtable on air and missile defense that the Missile Defense Advocacy Association (MDAA) hosted yesterday. Struve took the place of Air Force Brigadier General Paul Murray, NORAD’s Deputy Director of Operations, who had been “called into a four-star meeting,” according to MDAA Chairman and Founder Riki Ellison.

With regard to critical infrastructure protection, Struve laid out the current situation in the following way:

Our potential adversaries have created significant capacity to reach us asymmetrically. Our forward layers, our allies, our partners, our forward combatant commands and geographic commands, have largely kept those threats away from the United States. But as we look into threats from cyber actors, space threats, as well as kinetic conventional cruise missiles, which have [seen] significant improvement on the part of China and Russia in recent years, those create avenues that can create havoc in the homeland while we are trying to project our power forward to potentially a regional conflict.

So, the thing that I really want to emphasize here is that the homeland is not a sanctuary any longer. There are opportunities for our adversaries to employ weapons from distances that they could strike critical infrastructure in the United States early in a conflict and create some challenges for us to produce our military power.

And when we look at our deterrence model, we’ve had a lot of capability since really World War II to have deterrence by punishment. That nuclear deterrent is the underpinning of our entire deterrence model. And it’s that ability for us to respond in kind and protect our homeland.

But as our adversaries have built the capability to strike us conventionally, they feel like that they have [an] opportunity below the nuclear threshold to strike us and potentially keep that conflict from going nuclear. And it is this avenue where we really need to work to close gaps and be able to protect the homeland more completely. …

Something that I haven’t really talked about is what are we doing on the risk mitigation front, and that’s the ability for us to actually defend. And there’s two sides that we think about when we think risk mitigation. It’s our ability to deny those threats, and, when we talk about these kinetic conventional weapons, it’s hardening, redundancy, resiliency on some of our critical infrastructure. Not every piece of our infrastructure is going to be taken out with one of these conventional-size weapons, but some things are particularly vulnerable. So we view this as a whole-of-government approach on being able to protect that infrastructure.

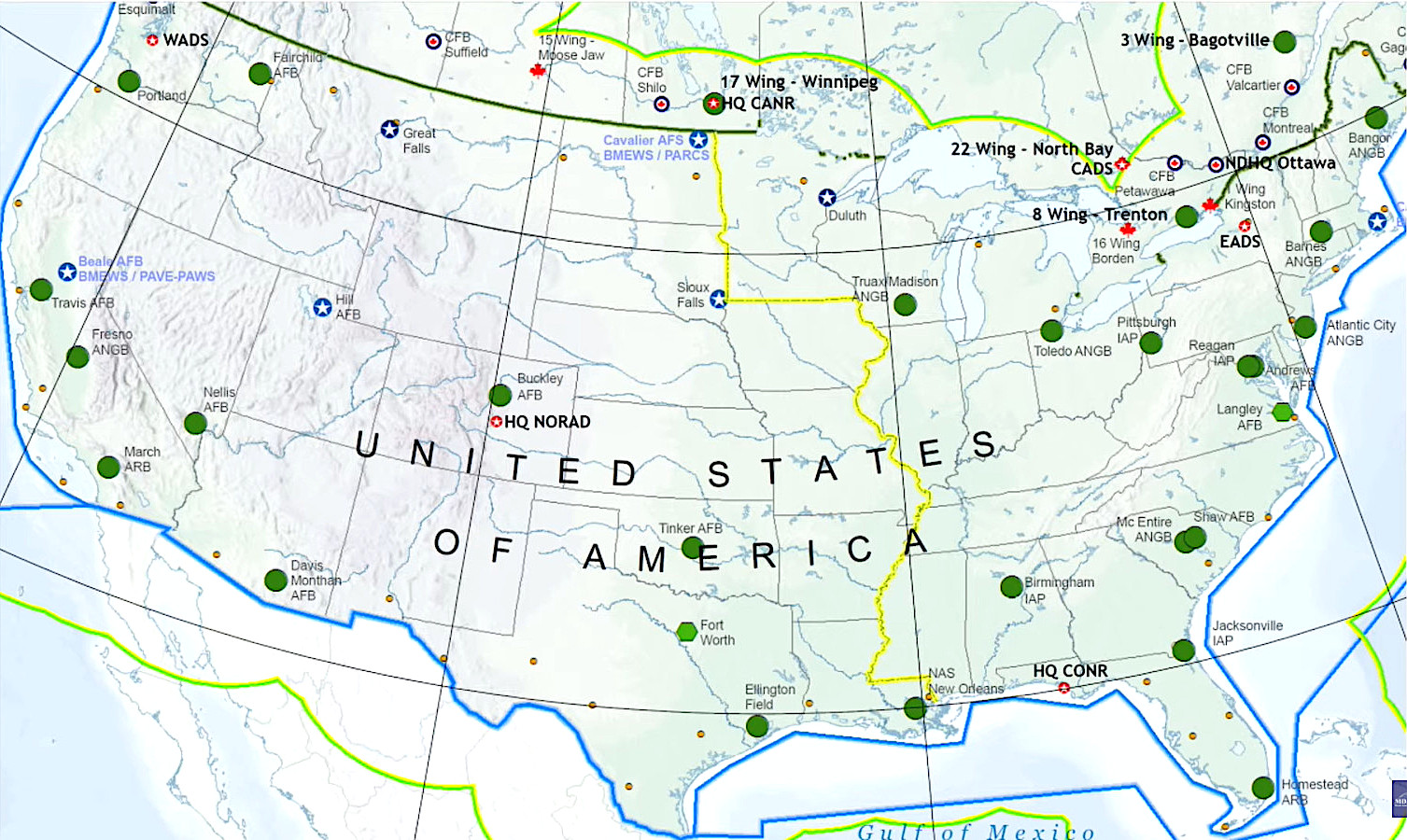

And then, after that, we would place defenses on key critical infrastructure nodes. It’s infeasible that we can place kinetic, you know, surface-to-air missile batteries over the entirety of the United States, Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, and Canada. By the time we fielded such a system, it would probably — they would’ve found a way around it anyways. So we are working closely with OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense] and the National Security Council on where are we going to place those limited ground-based air defense assets that we’ll have in time of conflict to really change our adversaries’ calculus about their efficacy of being able to execute an attack on the U.S. That can be everything from how we’re organized today, which would be our fighter aircraft at more than a dozen, a couple dozen locations across the U.S., that can intercept conventional cruise missiles with mixes of AESA and non-AESA fighters, as well as Alaska and Canada. It’s our limited area defenses, you know Patriot-type missile systems that we can deploy in time of crisis. But it’s also our persistent capability that we currently employ in specific areas, such as the National Capital Region. Those are systems that, based on increasing threats from both the air and sea, that we need to be able to continue to develop, generate, and put in those key critical infrastructure locations so that we can change the calculus of our adversaries.

You can watch the entire roundtable discussion via YouTube below.

Struve was correct in saying that it would be a costly and time-consuming endeavor to establish a nationwide surface-to-air missile network that enemies would undoubtedly develop counter-countermeasures against. Unlike some other countries, including many potential adversaries, such as China, the United States does not currently have SAMs strategically deployed on a permanent basis across the country. The U.S. military did have this kind of integrated network of SAM sites for a time during the Cold War but had shut them all down by the end of the 1970s.

At the same time, what is left unsaid here is that the U.S. military simply does not have anywhere near the capacity at present to deploy ground-based air and missile defenses to protect every key piece of infrastructure in the United States. As it stands, the only real “persistent capability” in this regard that the United States does have in place, as Struve noted, is in the National Capital Region (NCR). This air-defense force consists of batteries equipped with the National Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS), which uses the AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM), and fixed and Humvee-mobile versions of the Avenger system, each armed with Stinger short-range heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles, as well as a .50-caliber machine gun. Various radars and other sensors systems are positioned in the NCR to detect a variety of different types of threats.

The photograph in the Tweet below, taken during an incident in 2019, shows a fixed Avenger system in Washington, D.C.

Otherwise, the U.S. Army has around 18 Air Defense Artillery Battalions equipped with Patriot, the service’s main surface-to-air missile system. Each one of these battalions has between three and five batteries, depending on their exact composition. Last October, elements of the 1st Battalion, 44th Air Defense Artillery Regiment, out of Fort Hood in Texas, conducted a training exercise that saw them deploy to a commercial airport. This, in part, demonstrated how Patriot batteries could be sent to protect nonmilitary sites.

However, not all the Army’s Patriot units are available to be deployed inside the United States in a crisis. Five of them are overseas on a permanent basis — two in Germany, two in South Korea, and one in Japan. Two more are dedicated training units.

The Army has some six more batteries of Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems designed to engage incoming ballistic missiles, one of which is permanently based on Guam and another of which is forward-deployed to South Korea.

The service just recently established two more batteries with the Israeli-made Iron Dome system, which focuses primarily on cruise missile defense. One of those units is now headed for a temporary experimental deployment to Guam. In September, the Army awarded a contract to defense contractor Dynetics for the purchase of a similar system, known as Enduring Shield, to meet cruise missile defense and other requirements.

The Army and the Marine Corps have additional units equipped with Avengers, as well as shoulder-fired Stingers, that could provide point defenses around various sites, including against incoming cruise missiles. The Army is also in the process of fielding a new short-range air-defense system based on the Stryker 8×8 wheeled armored vehicle, which has Stingers, as well as Hellfire missiles and a 30mm automatic cannon. Additional systems, including ones equipped with directed-energy weapons, are now in development.

It’s important to remember that, during an actual crisis, demand for these relatively limited ground-based air-defense assets would also come from commanders around the world, who would be faced with a multitude of air and missile threats themselves. Beyond cruise and ballistic missiles, drones (including various tiers of armed types) present very real threats now to troops on battlefields abroad and at home, as well. The drone and missile strikes on oil-related infrastructure in Saudi Arabia back in 2019 provided a particularly notable wake-up call about these issues. The War Zone has, on multiple occasions, specifically highlighted the potential danger that small drones pose to American domestic critical infrastructure, as well as U.S. military activities.

Struve did rightly point out that American fighter jets, as well as their Canadian counterparts, provide the primary layer of air and missile defense, including against incoming cruise missiles. However, one of his fellow panelists at the MDAA roundtable, Air Force Col. Jason Nalepa, the commander of the 173rd Operations Group, part of the Oregon Air National Guard’s 173rd Fighter Wing, noted the “tyranny of distance” that limits how quickly fighters can respond to threats after scrambling from their bases around North America. In addition, those jets simply can’t be in every place at once and only carry so many missiles, further underscoring the importance of ground-based assets positioned at or near critical sites to provide additional layers of more localized protection.

All this clearly requires the kinds of discussions that Struve says are happening now about how the U.S. military can best use the assets available to mitigate increasing risks, particularly from conventional long-range cruise missiles that can be launched from aircraft, submarines, and ships, including even potentially non-descript commercial cargo vessels. His comments also raise clear questions about how the United States can and should expand its capacity to provide air and missile defenses domestically going forward.

In addition, NORAD’s vice director of operations highlighted the importance of existing integrated sensor networks, such as the North Warning System, along with future ones and other forms of intelligence in detecting potential threats or even helping to prevent crises from turning into full-blown conflicts, to begin with. “What we really need to be able to have is a complete, integrated system of … sensors, from the sea floor to on orbit, that are going to be able to detect any type of one of those threats, so that we can have that warning capacity to be able to inform our national leadership and take action,” he said.

“We’re also working heavily in the information dominance phase, and that would be the ability to take data from old sensors that were specifically calibrated [to detect certain threats] and [that] leave about 90% plus of their data on the cutting room floor… [and] being able to put [new] back-end processing on some of those sensors,” he added. There is a desire to “integrate that with… ‘left-of-launch‘ intelligence, to be able to give us more time and space … something that every commander needs to be able to deescalate a conflict,” as well.

Since 9/11, NORAD has been working toward fielding new and improved distributed sensor and networking capabilities, as well as additional interception capacity, first under the Homeland Defense Design effort and now under a new overarching initiative known as the Strategic Homeland Integrated Ecosystems for Layered Defense (SHIELD). One of SHIELD’s more notably “spiral” developments has been the integration of new AN/APG-83 Scalable Agile Beam Radars, a new active electronically scanned array type, onto Air Force F-16C/D fighter jets, giving them improved abilities to spot and engage various threats, including low-flying cruise missiles. You can read more about this project here.

The development and fielding of new or improved surface-to-air missile systems are reportedly among SHIELD’s goals, as well. “The SHIELD strategy seeks ways to reduce costs by optimizing for defense of domestic locations,” according to a story Air Force Magazine published in January. “Patriot surface-to-air missile defense systems, for example, were originally designed to protect Army units while on the move.”

“They’re built to travel over rough terrain and hardened to operate through chemical or biological attacks,” it continued. “NORAD believes it can cut costs by stripping out some of those features while retaining its advanced fire-control system.”

SHIELD would also seem to present increased demand for new, shorter-range systems, such as Dynetics’ Enduring Shield. However, these types of air defense systems would only be able to cover relatively small areas. This, in turn, would require the purchase of a larger number of them to ensure that they would be available in the quantities necessary to provide any sort of robust coverage domestically, as well as meet demands for commanders downrange.

In the meantime, the U.S. military’s plan clearly is to prepare to deploy air-defense assets available now to protect critical infrastructure, if necessary. However, as NORAD’s Struve notes, the limited number of surface-to-air missile systems means, at least for the foreseeable future, that there will have to be discussions about what sites would get additional protective shields during an actual crisis.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com