The U.S. Air Force recently highlighted some fascinating pictures showing various tests that have been conducted using the High Speed Test Track at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico over the past seven decades or so. This test track had gained additional relevance in recent years amid a resurgence of interest across the U.S. military in hypersonic weapons and other air vehicles, and the Air Force is now looking at ways to modernize the system to ensure it can continue to support those efforts.

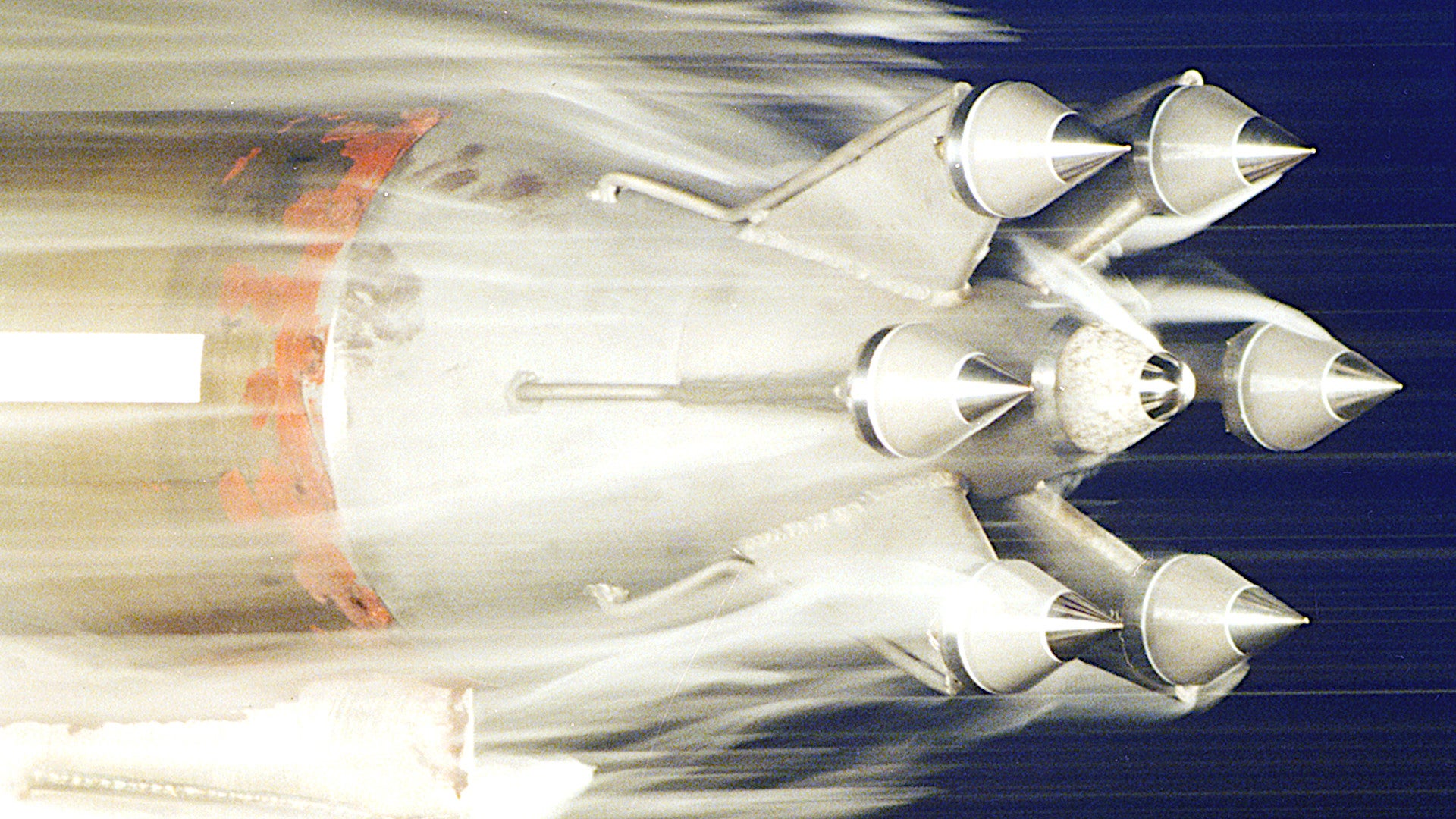

The 846th Test Squadron currently oversees the operation and sustainment of the Holloman High Speed Test Track (HHSTT). The 846th is what is known as a geographically separated unit and is assigned to the 704th Test Group, which is situated within the Arnold Engineering Development Complex (AEDC) at Arnold Air Force Base in Tennessee. The HHSTT is used to see how a variety of test articles, including those related to weapon systems, such as bunker-buster bombs, as well as ejection seats and various other kinds of components for aircraft and other aerospace vehicles, work at extremely high speeds or otherwise respond to the stresses of moving at those very high velocities. That latter category of testing includes, among other things, seeing how rain impacts payloads traveling at high speed. A picture from one such “rain erosion” test is seen at the top of this story.

The test track dates back to 1949, when work first began on the original section, which was 3,400 feet long. Actual testing using the system began the following year.

A test that took place on Dec. 10, 1954, is by far the most famous of the work done at the track in the 1950s. On that date, Air Force Lieutenant Colonel John Stapp was strapped into a metal chair on a rocket-powered sled, dubbed Sonic Wind No. 1, and blasted down the track. The sled hit 630 miles per hour and Stapp was subjected to 40 Gs of force during the ride, leaving him with broken ribs and a detached retina among other injuries.

“Stapp survived and, in the process, demonstrated the incredible forces the human body is capable of withstanding, thereby providing a greater understanding of human tolerance to high-speed aircraft ejections,” according to the Air Force. “Stapp’s work also aided in the development of safety belts capable of tolerating a greater amount of force.”

He also broke the land speed record at the time, earning the title of “Fastest Man on Earth.”

The Air Force continued to utilize the track, and expand its capabilities, in the following decades. In 1982, another rocket sled, with a 25-pound payload instead of a person, set a new land speed record for an uncrewed platform. The unspecified test article hit a peak speed of 6,119 miles per hour. For comparison, the current land speed record for a vehicle with a person in it, set by Andy Green in 1997 using a jet-powered “car” called ThrustSSC, sits at just over 763 miles per hour.

The HHSTT’s land speed record stood until 2003, a year after the completion of the fifth and most recent extension of the track, when Air Force testers launched a rocket sled with an unknown 192-pound test article that reached a speed of 9,465 feet per second, or 6,500 miles per hour. At the altitude at which the test track sits this is around Mach 8.5. For reference, hypersonic speeds are generally defined as anything above Mach 5.

That record has since been broken, too, with a test that the Air Force said hit Mach 8.6, seen in the video below, which you can find out more about here.

At present, the HHSTT is 50,971 feet, or around 10 miles, long. However, its ability to conduct certain tests is limited by the fact that only a wide-gauge track runs the full length. A parallel set of narrow-gauge rails only run for around four miles of the track’s total length. The wide-gauge portion of the system is “mainly used for egress, dispense, and guidance testing,” according to the Air Force.

“Currently, recovered high-speed – those of Mach 3 or more – and rain erosion tests are limited to one of the 10-mile-long rails in a monorail configuration,” according to an official Air Force news item published earlier this month. “The monorail configuration limits the size of test articles to small, light test articles, or coupons, due to roll stability issues at high velocities.”

The 846th is currently looking into three different courses of action, details of which the Air Force has not yet released. However, each one is centered on the main goal of extending the narrow gauge rails to run the full 10-mile-length of the track.

When actual work to modernize the HHSTT might begin, how much it might cost, and how the Air Force might pay for the upgrades are all uncertain. “The 846 TS [Test Squadron] is currently pursuing military construction funding, but there is a chance of receiving funding through other agencies, such as TRMC [the Pentagon’s Test Resource Management Center],” the Air Force’s official news story explained. “Because the 35 percent architecture and engineering, or A&E, design is not yet completed, a preferred COA [course of action] has not yet been chosen at this time. U.S. Air Force policy and Congress require the completion of a 35 percent A&E design before the project is funded to help avoid cost overruns due to inadequate planning.”

As already noted, the plethora of hypersonic aerospace projects that are publicly ongoing across the U.S. military, with many more almost certainly taking place in the classified realm, only underscores the importance of specialized high-speed test facilities like the HHSTT. “The Holloman High Speed Test Track is a truly unique national asset with a 70-plus year history that is worthy of preservation and modernization to continue its test and evaluation heraldry into the next century,” Lee Powell, the 846th’s Capability Development Element Chief, said an interview for the recent Air Force piece on the modernization plans.

The pictures that the Air Force showcased recently certainly highlight the unique and often record-breaking work that has already been done at the track at Holloman over the past 72 years. It now looks set to become an even more important part of the service’s testing ecosystem in the years to come.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com