Sea mines are among the most widespread, deadliest and strategically effective anti-access/area-denial weapons available today. A huge selection of sea mine types can be deployed by submarines, ships or aircraft—from simple floating contact mines to smart “influence mines” that lay in wait until a target’s pre-programmed signature triggers their attack. Yet 239 years ago, it was a group of break-away colonists fighting for their independence from the British Crown who put the modern idea of a sea mine to work for the first time.

David Bushnell, the same Yale graduate and secretive naval weapons inventor who built the first attack submarine, the Turtle, also designed and built the first modern naval mines for a not-quite-yet United States.

Very crude naval mine-like devices were designed by Chinese warlords hundreds of years before the Revolutionary War. They used ox bladders as dry bags and pig intestines as snorkels, as well as very crude timed or manual cable fuses, each with questionable success. Centuries past before Bushnell used his naval explosives knowledge to come up with a totally different trigger mechanism, one that was fired when the mine struck an object, making the naval mine concept much more relevant and deadly.

Bushnell’s contact-triggering “keg” mine was made up of a fairly simple watertight wooden keg filled with gunpowder and attached to a float. The idea was to float the mines, also called torpedoes at the time, with the prevailing current towards enemy warships docked or anchored in a channel. Once the mine came in contact with something solid the flintlock fuse would be punched, then the keg would detonate.

On August 13, 1777, Bushnell and his team attempted to use his contact-trigger mines for the first time, deploying two of them in an attempt to sink the sixth-rate British frigate the HMS Cerberus anchored in Black Point Bay, just west of New London. Bushnell guided a small whaling boat in the darkness up toward the frigate and released two mines in tow far apart in hopes one would ride the current accurately to the hull of the Cerberus.

One of the two mines floated right on course toward the Cerberus when it was snared by a schooner that was anchored between Bushnell’s release point and the targeted frigate. The curious British sailors aboard the schooner hoisted the weapon aboard when it detonated, killing three sailors, severely injuring another and sinking the schooner.

The HMS Cerberus remained unharmed.

Although the mission was not a total success, it was the first time a ship had been sunk by a modern contact mine and the event caused the HMS Cerberus, which had been prowling the waters off of Connecticut, to redeploy immediately to Newport so the Captain could warn his Royal Navy superiors of the new weapon he’d encountered.

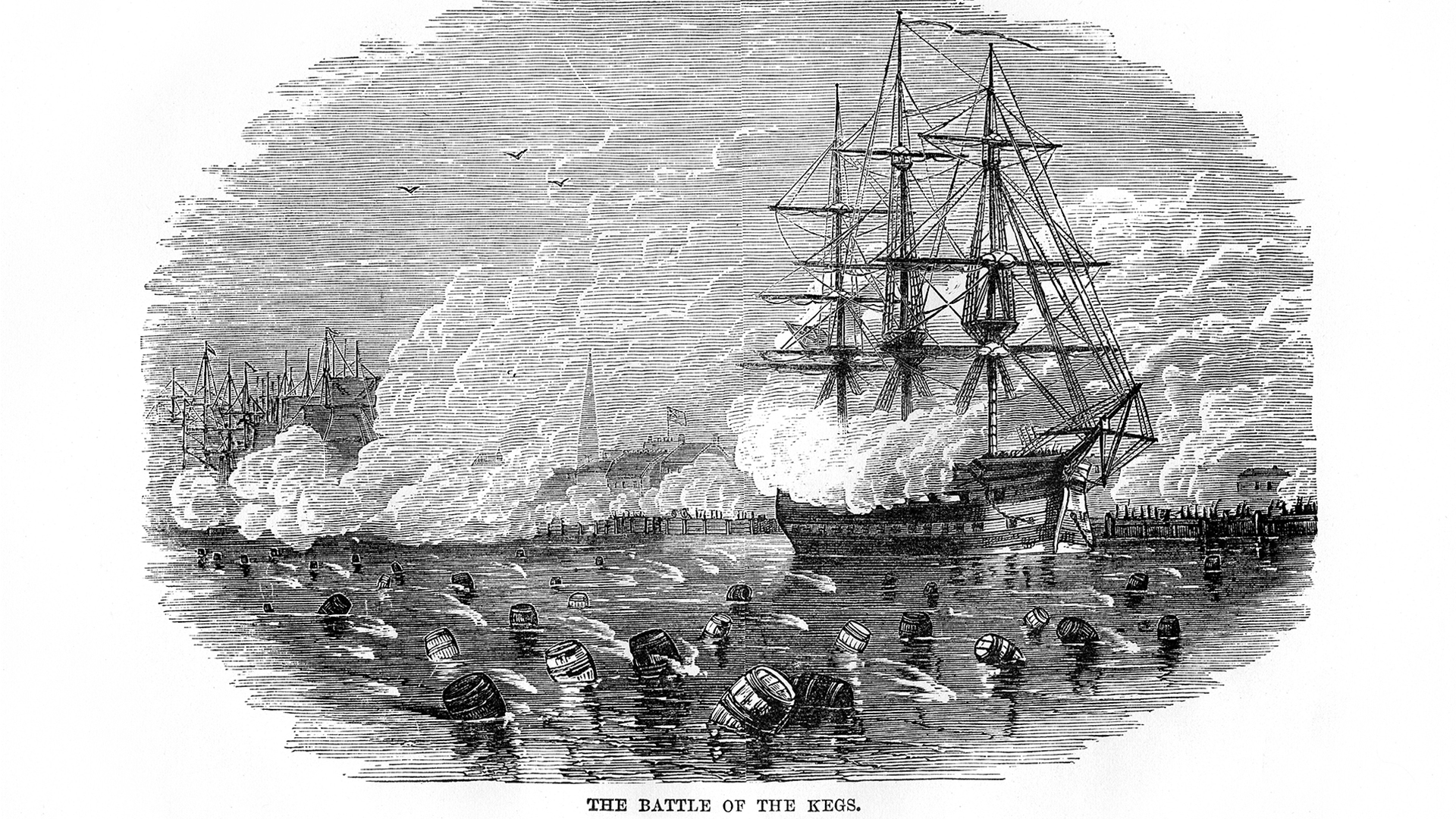

Bushnell tried again four months later, this time unleashing 20 slightly improved mines on the Delaware River, near Bordentown, New Jersey. The plan was to float the mines down the river and sink British ships anchored in Philadelphia harbor. Although none of the keg mines hit a large British vessel, a small boat was struck, killing a couple of young boys. Still, the massive blast freaked out British naval commanders so much that they ordered pretty much anything floating in the water to be shot from a distance. For over a day the British waged a full-out war on Bushnell’s mines and everything else floating on the Delaware River.

The event was immortalized a month later in the rousing propaganda ballad, “The Battle of the Kegs.”

Although George Washington had been very supportive of Bushnell’s secret maritime super-weapons, this was the last time mines were used during the revolutionary war. Yet the technology would become a staple of warfare in the decades and centuries that followed.

In fact, when Admiral David Farragut coined the phrase “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” at the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War, he was actually referring to naval mines—many of which were very similar to Bushnell’s Keg invented nearly a century earlier during America’s fight for independence.

Happy 4th of July everyone!

Contact the author at tyler@thedrive.com