Lockheed Martin’s famous Skunk Works advanced projects division has opened a new cutting-edge manufacturing facility at its campus in Palmdale, California, which is part of the U.S. Air Force’s Plant 42. The company says that the technologies it will employ in this new “factory of the future,” blandly named Building 648, will help it drastically speed up and otherwise improve how it designs and produces advanced aerospace vehicles, including stealth fighters and drones, hypersonic missiles, and more. Beyond that, however, this factory is the centerpiece of a larger transformation going on within Skunk Works that could potentially revolutionize the development and production of even very advanced aerospace concepts, industrial capabilities that could be increasingly essential for the U.S. military to maintain its competitive edge.

The War Zone was among a select group of outlets given an opportunity to visit Skunk Works and attend the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the 215,000-square foot Building 648, which Lockheed Martin representatives have described as an “intelligent, flexible, advanced manufacturing facility,” on Aug. 10, 2021, as well as tour other relevant portions of the overall facility at Palmdale. The factory is the “cornerstone” of approximately $400 million worth of investments the company has made to help expand its capabilities and capacity at what is formally known as Plant 10 in recent years, which has already led directly to the creation of 1,500 new jobs since 2018.

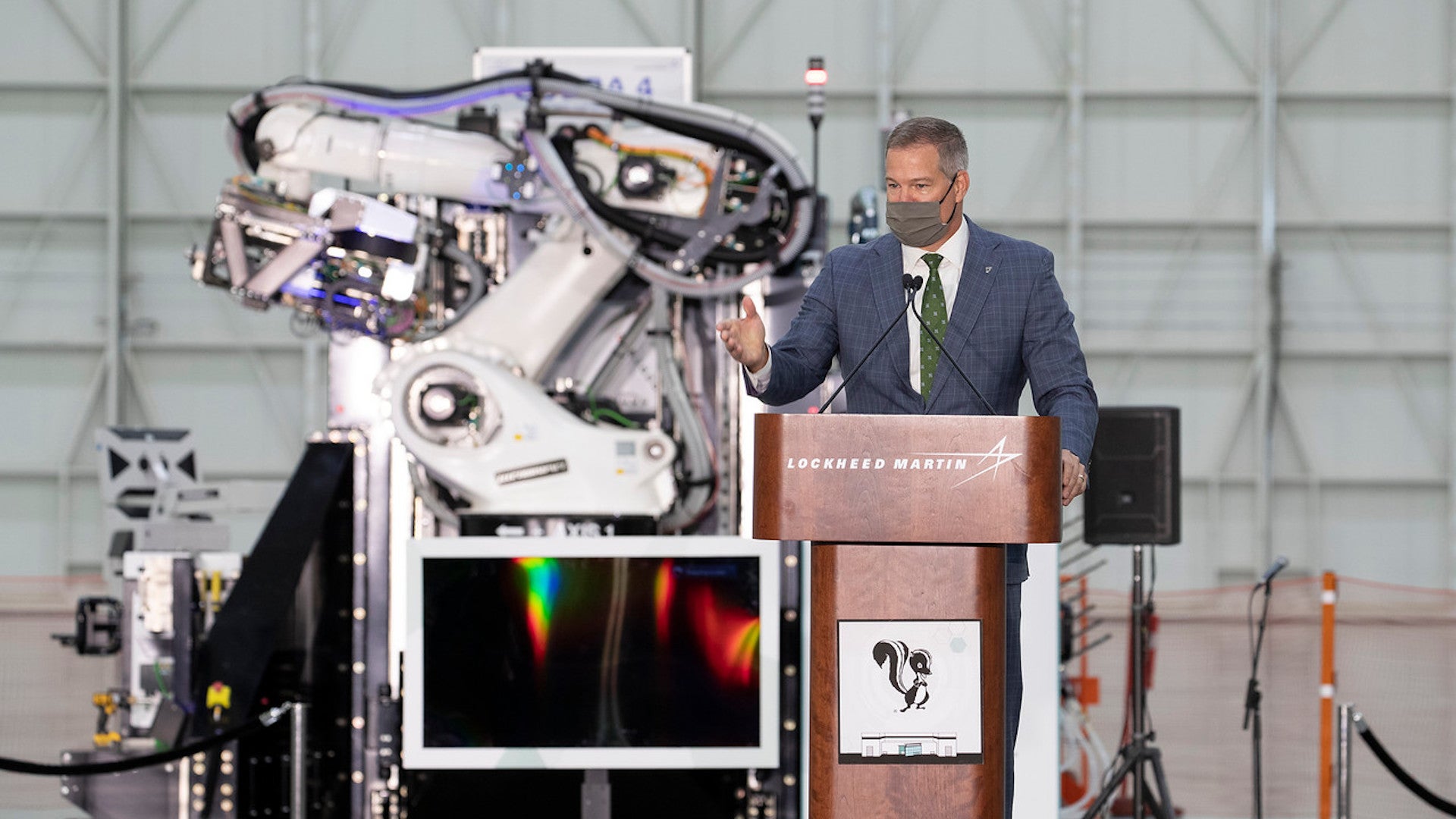

“While what we’re doing hasn’t changed, how we’re doing it has changed,” Jeff Babione, Vice President and General Manager of Skunk Works, to the reporters who traveled to Palmdale to get a briefing ahead of the ribbon-cutting ceremony. “So, for some time, Lockheed Martin, at the corporate level, and across the entire enterprise, has been focused on transforming virtually everything we do in the business, from writing requirements, to writing contracts, to designing and developing those technologies, to manufacturing technologies, to sustaining those technologies in the field. This is our digital transformation.”

Building 648 is a prime reflection of these new processes and how Lockheed Martin plans to implement them inside and outside of Skunk Works. Though the factory’s shop floor was largely empty during the ribbon-cutting event, that is, in itself, a key aspect of Lockheed Martin’s plans for the high-tech facility.

Over the years, Skunk Works has had to expend significant time and resources to simply set up workspaces for new programs within buildings across its campus in Palmdale. One Lockheed Martin executive quipped that the local companies who provide the chain-link fences that segregate the different areas within the various hangars at Plant 10 can expect reliable work given how often those spaces have to be reconfigured. Beyond just building those alcoves, new, dedicated tooling also often has to be procured and then moved into place, especially when it comes to manufacturing prototypes or carrying out limited production runs of certain designs.

Lockheed Martin’s goal with Building 648 is to do away with a significant amount of the initial setup through increased automation, particularly with the employment of large, advanced robots from Electroimpact. Right now, the company has four such robots, known as Combined Operation: Bolting and Robotic AutoDrill systems, or COBRAs. These are, in their present configurations, capable of drilling and countersinking holes in various materials, including composites and titanium, as well as bolting and fastening structures together. These machines, one of which is seen in the background of the photo at the top of this story, could gain additional functionality as time goes on, as well. Building 648 itself also has very advanced climate controls, able to keep the interior temperature within plus or minus two degrees of a specific setting, regardless of the conditions outside, to support work using various, often environmentally sensitive materials. These materials often have to be fitted or even fused together, so controlling their expansion during manufacturing is key.

Skunk Works has already used these robots and demonstrated some of their advanced capabilities on the X-59A Quiet Supersonic Transport testbed, or QueSST. This experimental aircraft is under development for NASA as part of a project to explore ways to mitigate the shockwave and associated noise from sonic booms.

A company representative told The War Zone that the Electroimpact robots had drilled more than 7,519 holes in structures for the X-59A, at a rate of one hole every 21 seconds, and that only 23 of those needed to be redrilled. Improperly drilled holes can easily lead to delays and cost increases, especially when it comes to the production of stealthy aircraft, where these kinds of mistakes can impact the radar-absorbing and deflecting qualities of the design. This level of accuracy in machining also helps ensure uniformity in parts, including spares, which is important for sustaining systems as time goes on. Altogether, this is a major step up from building advanced aircraft largely by hand, as Skunk Work has done for decades.

In addition to simply being able to quickly and accurately drill and fasten structures for advanced aircraft, the robots are capable of being programmed to perform this work autonomously, with a human operator present mainly to provide an additional margin of safety. The robots are mobile, which means they can go to where the work is, rather than the other way around.

More importantly, that latter capability means that a single robot, using pre-programmed instructions, will be able to move relatively rapidly from one task to another, regardless of whether that involves drilling holes in something like the X-59A or bolting together parts for an advanced manned or unmanned aircraft. In turn, the hope is that this will significantly reduce the need for project-specific tooling, as well as make it easier to reconfigure spaces within Building 648, or any similar facility, when shifting from work on one program to another, giving the entire enterprise a very modular feel. There will be nothing, not even basic furniture, permanently nailed down on the floor of this new factory.

The work that will go on in Building 648 will also leverage advances in both augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR), combined with advances in digital engineering, to further improve the manufacturing processes. What this means in practice is that personnel on the shop floor, as well as engineers elsewhere, will be able to check that physical parts being built or assembled look and behave structurally the way they were expected to when compared with digital models. If problems arise, or there is a desire to change certain things, individuals could use AR or VR to immediately begin exploring potential fixes or alterations without necessarily have to assemble or disassemble entire components first.

AR and VR also allow the functioning of an entire system to be explored, and tweaked if necessary, without needing to have a complete physical article fully constructed. This means, for example, that engineers and technicians can check to make sure that access panels, and what’s behind them, are accessible to workers that will service the aircraft. Assembly of components of specific products can leverage AR, giving workers a far better context of how the operations should occur, which should increase manufacturing speed, streamline training, and enhance quality control.

All of the technologies that Skunk Works plans to employ within Building 648 itself are, however, just one part of a much bigger picture. This is the over-arching “digital transformation” that Vice President and General Manager Babione spoke to ahead of the ribbon-cutting.

It might seem innocuous, but building 648 will have wi-fi inside, despite being approved to work on projects at some of the highest levels of classification with the U.S. government, two things that are typically incongruous and something Babione said was a first for a Department of Defense contractor. Some 85 percent of everything that goes on at Skunk Works is classified. So, what that means is that data can be more readily and flexibly sent to and from the shop floor and engineering spaces elsewhere within Plant 10 without the need for physical links. This is necessary to enable Skunk Works’ vision of mobile robots moving seamlessly from one project to another across the factory and how reconfigurable the facility will be, as a whole.

One Lockheed Martin representative stressed that the individuals involved in the various aspects of the design and manufacturing processes were not necessarily doing different types of work compared to what they had done in the past, but that the process is more vertical now than horizontal. What the means in practice is that, instead of different teams completing their portions of a project and then passing them off to the next group in a sequential process, they are now working more in parallel and are more actively coordinating along the way.

This broader concept has been enabled in no small part through the development of digital modeling and engineering toolset called StarDrive. This builds on Skunk Works’ already long-established reputation as a pioneer in advanced and rapid prototyping capabilities, including high-fidelity modeling.

Various elements of the StarDrive team have already been demonstrating what the toolkit, combined with advanced manufacturing capabilities now expected to be exploited to the fullest in Building 648, can do through various modeling and digitally-enabled manufacturing efforts. The X-59A program, one of Skunk Works’ few unclassified programs, has provided a useful springboard for StarDrive to test out its advanced processes.

One demonstration effort conducted under StarDrive, known as Polaris, used the entire digital toolkit to produce a 1:1 copy of a section of the X-59A that included metal and composite components. In addition to demonstrating how all of this is work to produce a real, physical product, Polaris also showed how Lockheed Martin will be able to bring third-party suppliers right in at the beginning of the process.

Portions of the Polaris structure were built off-site by Spirit AeroSystems using digital design data provided by Skunk Works. In existing manufacturing processes, subcontractors typically send components to places like Skunk Works’ Plant 10, where they are then prepped for assembly, including the drilling of various holes, and then painstakingly fitted together.

Using the StarDrive tools, Spirit was able to have its segments more or less ready to go before shipping them, greatly reducing assembly time. As an example, the pinning of the composite structures to the metal frame on Polaris, a process that Skunk Works representatives said involved fastening some 1,500 individual pins and that would typically take hours, was completed within approximately 30 minutes.

Renee Pasman, the Director of Integrated Systems at Skunk Works, described the ultimate aim here as being to make the process akin to assembling extremely “high-quality Ikea furniture,” except that the final product doesn’t “wobble” at all.

The name Polaris, the formal moniker for what is commonly referred to as the North Star, was specifically chosen to reflect its nature as a “pathfinder” program for future Skunk Works programs. The StarDrive team is already working on a separate initiative, dubbed Speed Racer, which will serve as a different kind of end-to-end demonstration of the process, taking a digital design and turning it into a flying prototype.

The Speed Racer vehicle itself, which was first publicly disclosed in 2020 and that you can read more about here, is a small missile-like drone. During the events at Palmdale, Skunk Works disclosed that the name, which is an acronym, stands for Small Penetrating Expendable Decoy Radically Affordable Compact Extended Range, and that there is an as-yet-undisclosed customer for this air vehicle. It’s not clear if that entity is presently planning on acquiring Speed Racers simply for research and development purposes or has an eye toward eventually employing them operationally in some way.

Skunk Works also provided some basic details on other StarDrive subprojects, including Sirius, which was focused on the “model-based systems engineering” of a notional tailless delta-wing fighter jet-type aircraft, and Charlie, a similar effort in some respects to Polaris, but that produced a smaller and less complex physical component.

The digital toolset is also be used in work related to the modernization of the F-16 Viper fighter jet design. Earlier this year, the Air Force announced that it had hired Wichita State University’s National Institute of Aviation Research (NIAR) to create a very high-fidelity 1:1 digital model, or “digital twin,” of an F-16 to help support such efforts. Lockheed Martin’s StarDrive team has also been involved in that project.

“Using a proven platform like the F-16 to advance digital twin data models allows our team to demonstrate a further reduction in lifecycle cost for sustainability while also introducing additional capability through digital thread continuity,” Aaron Martin, the StarDrive Program Manager at Skunk Works, said in a statement in June. “This project is indicative of how Lockheed Martin’s technology investments will allow us to make even faster progress on future programs.”

StarDrive, together with the capabilities that Skunk Works plans to put into use in Building 648, are all intended to allow engineerings and technicians to get their various jobs done faster, more efficiently, and more effectively, even when dealing with very high-tech design concepts and materials. This, in turn, is expected to dramatically reduce the time it takes to develop those designs and build them, as well as the costs of doing so.

While these benefits would be good in any context, they will be especially valuable if they can be employed effectively with regards to advanced aerospace projects, especially on military programs, such as future manned and unmanned stealth aircraft. Historically, those kinds of development programs have been extremely costly and time-consuming, often creating new problems down the road as demands emerge to integrate new, more up-to-date technology into those designs.

A prime example of this is the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, which began at Skunk Works, and has faced significant development and production hurdles throughout its history already and is now facing worrisome growth in operational and sustainment costs. “We’re in a situation that bears some resemblance to one that I had earlier on, around Lot 4 or so, when there were a lot of design issues on a plane that hadn’t been resolved, and we were in the process of buying airplanes that were going to need extensive modifications,” Frank Kendall, who was just recently confirmed as Secretary of the Air Force, told Air Force Magazine about the Block 4 upgrade package for the Joint Strike Fighter in a recent interview.

The Air Force, among other F-35 operators, see those improvements, which you can read more about here, as critical to the F-35’s viability in future high-end conflicts. However, it is unclear when they will find themselves integrated into the bulk of operational Joint Strike Fighter fleets.

In recent years, the Air Force, in particular, has similarly been talking about wanting to find ways to upend traditional development cycles for advanced air vehicles, and achieve efficiencies similar to those seen in the commercial automotive and aviation industries. In 2019, Will Roper, then the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, first described the basic outline of one potential new, rapid, iterative design concept, called the Digital Century Series, which would rely heavily on digital engineering techniques and focus on small production runs. A facility like Skunk Works’ Building 648 could make this ambitious idea more plausible.

U.S. military officials have also made it increasingly clear publicly in recent months that they feel traditional development processes are too slow to keep pace, capability-wise, with potential adversaries, especially near-peer opponents, such as China. “What I don’t know, and what we’re working with our great partners, is if our nation will have the courage and the focus to field this capability before someone like the Chinese fields it and uses it against us,” Air Force General Mark Kelly, head of Air Combat Command, said earlier this year, referring to his services Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program. NGAD is a multi-prong advanced development effort that has produced at least one flying demonstrator design already.

With all this in mind, it’s perhaps not surprising that the main StarDrive workspace at Skunk Works, also known as Area M, has a large version of the iconic skunk logo that visitors are encouraged to sign and included a signature with “NGAD SML,” printed underneath. It was not readily possible to determine who this individual was from their signature, but SML here likely meant “Subject Matter Lead.” There is, of course, also the possibility, that this refers to the U.S. Navy’s NGAD effort, which is similar, but separate from the Air Force program of the same name. Lockheed Martin’s new developmental and manufacturing processes would, of course, be of interest to both of those services, along with other branches of the U.S. military, as well as foreign allies that have close enough relations with the U.S. government to potentially take advantage of them.

Of course, it remains to be seen whether or not Lockheed Martin’s plans for Building 648, or the rest of its company-wide digital transformation, will fully come to fruition. Though significant portions of the overall concept have already been demonstrated, it is still an ambitious undertaking and the company will need to prove that it can be scaled up, even on a modest level.

As already noted, Building 648 is just one part of a large expansion of facilities to handle almost exclusively classified work in Palmdale. This includes plans to build an expanded solar farm at Plant 10 that will be 10 times the size of the current one, which is already very large, and will allow the new factory to operate “off the grid.”

Other work at Palmdale includes the expansion of Building 638 to include an 8,000-square-foot hangar with the “capability to operate aircraft of varying thrust levels,” allowing engine testing to be conducted entirely inside the structure “to ensure external parties cannot see” what’s going on, according to a poster at the ribbon-cutting ceremony. The construction of thousands of additional square feet of storage space for classified articles was completed at Plant 10’s Building 645 and at Lockheed Martin’s Helendale Radar Cross Section Range, also in California just to the east Skunk Works’ main campus, earlier this year, as well. Work is expected to be finished on expanding Building 645, described only as a “secure classified intelligent facility,” in November.

In addition, Skunk Works’ also has workforces now at Lockheed Martin’s manufacturing facilities in Fort Worth in Texas, home of the main F-35 production line, and in Marietta in Georgia. However, the company stressed that, at least for now, Building 648 at Palmdale will be a unique facility in terms of its capabilities.

Lockheed Martin, as a whole, plans to spend around $2 billion over the next five years just in support of its digital transformation. So, all told, the company clearly sees these initiatives as potentially game-changing on a broad scale.

If the results meet the expectations, this could very well help revolutionize advanced aerospace development and manufacturing in the United States—which is what Skunk Works, at its very core, has always been about. This, in turn, could help offer the Pentagon, as a whole, a critical avenue to support its own digital transformation, which it clearly sees as a strategic necessity.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com