The U.S. Navy’s Cold War-era AIM-54 Phoenix long-range air-to-air missile, the primary fleet air defense armament of its F-14 Tomcat interceptors for four decades, was also adapted for surface launch from warships. The little-known Sea Phoenix project also involved installing the F-14’s fire-control radar on a ship and progressed as far as missile test launches.

The Sea Phoenix concept had emerged by the mid-1970s and was proposed as an alternative or a replacement for the early versions of the Sea Sparrow, which was another adaptation of an air-to-air missile for fleet defense. At that time, the air-launched AIM-54 was already in frontline use on the Navy’s F-14 fighters, coupled with the powerful AN/AWG-9 pulse-Doppler fire-control radar system as part of a sophisticated defense, primarily intended to defeat Soviet naval cruise missiles, and the long-range aircraft that carried them.

The origins of the Phoenix and the AWG-9 date back beyond the F-14 and can be found in the Navy’s Bendix AAM-N-10 Eagle and the Air Force’s Hughes GAR-9, two similar, but ultimately abortive long-range air-to-air missile programs. Superseding these, Hughes Aircraft began development of the Phoenix in 1962, and a first full-scale test of the missile was achieved on September 8, 1966, from an NA-3A Skywarrior over the Navy Pacific Missile Range. The AIM-54A became operational with the Navy’s F-14As in 1974.

While Tomcats launched from the deck of aircraft carriers were intended to provide an outer layer of protection for Carrier Battle Groups, the Sea Phoenix would have been installed on the carriers themselves, providing a closer, but still long-range defensive ring against any aircraft or missiles that may have made it through.

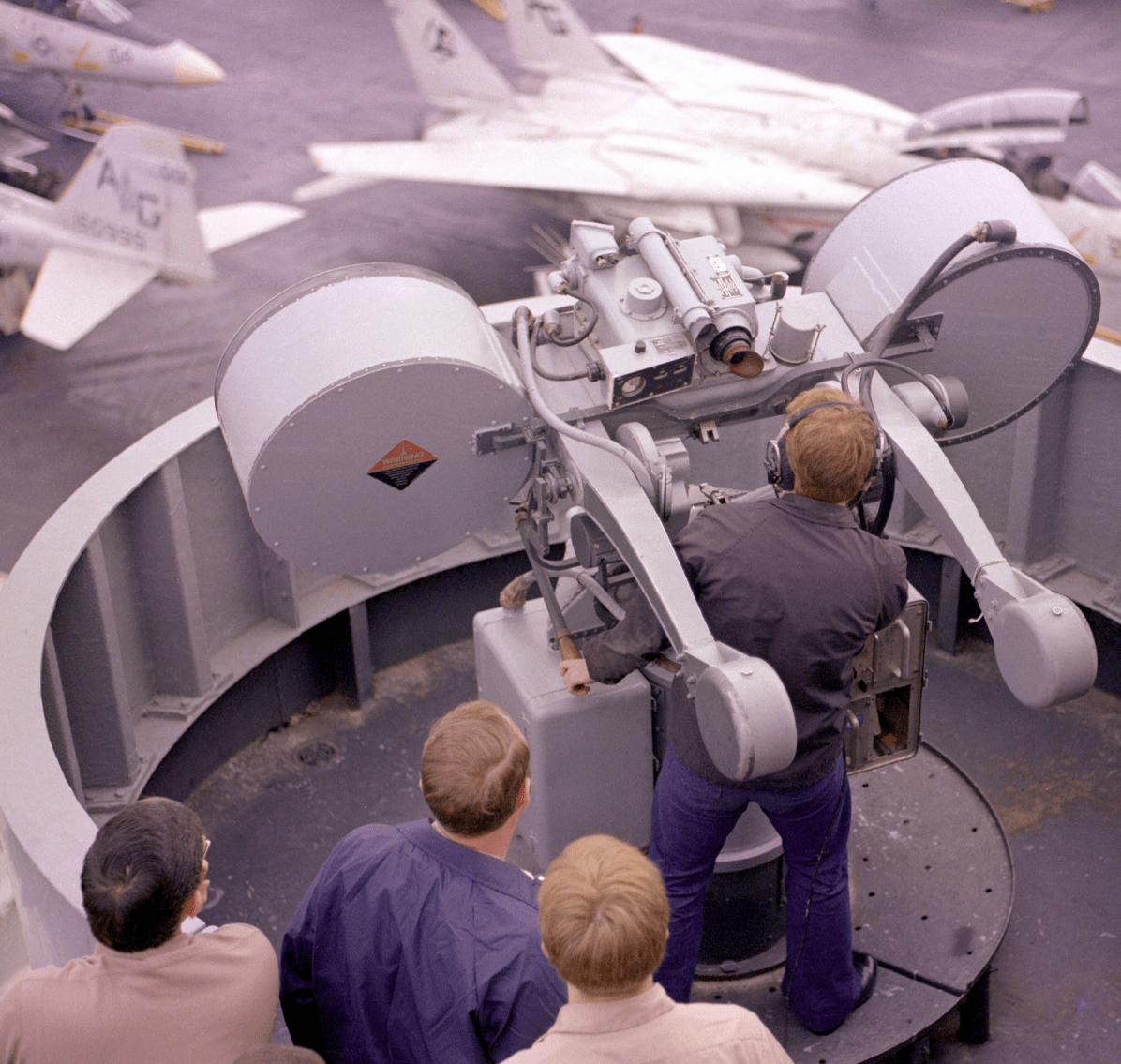

The plan was to install three launchers on each carrier so equipped, to provide full 360-degree coverage for each ship. Each of those systems would have been a standalone item, combining a fixed 12-cell launcher for Phoenix missiles, an AWG-9 radar, plus the various controls and displays required to operate it.

Installing the Sea Phoenix on a carrier, or on another warship, for that matter, was not expected to pose too many problems. According to Hughes Aircraft, responsible for building both the AIM-54 and the AWG-9, a full 27 of the 29 major components of the system could be added to a warship, with next to no modifications required.

The advantages of the Sea Phoenix would have included the ability to engage multiple targets simultaneously. After all, the AWG-9 was capable of tracking up to 24 targets simultaneously in track-while-scan mode and then engaging six of these with Phoenix missiles. That number was limited by the six AIM-54s that each F-14 could carry (reduced to four missiles for routine carrier-based operations), but potentially more targets could have been engaged using the Sea Phoenix system with its greater ‘magazine depth.’

The AIM-54 also offered very impressive performance for a missile at this time. In its original AIM-54A form, the weapon had an air-launched range of up to around 72.5 nautical miles and it could hit a top speed of Mach 4.3. However, this would have been reduced in surface-launched form, with the air-launched model gaining extra reach thanks to the speed and altitude of the launching aircraft.

In comparison, the air-launched AIM-7F Sparrow has a range of approximately 38 nautical miles, which is slashed to around 14 nautical for the Sea Sparrow’s RIM-7P missile. Nevertheless, despite the range penalty of the surface-launched AIM-54, which weighed a hefty 1,000 pounds, it’s clear that its performance would have far outstripped that of the Sea Sparrow in terms of range.

For shorter-range engagements, the air-launched AIM-54 employed active radar homing for the duration of its flight and this would likely have been the case for the shipborne version, too. The minimum engagement range for air-launch was around 2 nautical miles.

The original plans called for the Phoenix/AWG-9 combination to be installed on warships with little changes made to them but, “at a later stage, the system could be further enhanced by applying missile modifications to optimize it for the naval role,” according to the 1977 edition of Jane’s Weapon Systems. Unconfirmed accounts suggest there was a plan to install an additional booster stage, to address the reduction in range after surface launch, and this might have been the modifications referred to.

Tests of the surface-launched Phoenix missile included a firing from what was then known as Naval Weapons Center China Lake, in California, during which a standard version of the missile traveled a distance of 13.5 miles in 90 seconds. This test, however, was less concerned with evaluating end-to-end performance than it was the separation of the missile from its launcher, as well as safety aspects. If they did occur, no other such tests appear to have been documented.

Meanwhile, the 14th production example of the AWG-9 radar was installed aboard the missile-tracking ship USNS Wheeling, in 1974, where it “successfully detected and tracked multiple targets at both high and low altitude from the ship’s deck,” according to a report in the United States Army Combat Forces Journal. “In multiple target tests,” the report continued, “five aircraft were flown in the target area and successfully tracked.”

Unconfirmed reports suggest the AWG-9 radar was also tested on land, in a container van setup, at Point Mugu, California. This was likely in relation to a possible land-based mobile version of the Phoenix, reportedly intended for the U.S. Marine Corps. Few, if any details about this program are readily available, although it could perhaps have provided a notably potent air defense capability for the service’s expeditionary operations.

While the Sea Phoenix would also have offered much more in the way of anti-aircraft and anti-missile defense capabilities than the Sea Sparrow, it seems that its development was abandoned due to the high costs involved.

In addition, while the Sea Sparrow provided an intermediate to close-range point-defense capability, the same was not the case for the Sea Phoenix, which was by no means a dogfight missile and would have been of limited value against close-in, maneuvering threats. The AWG-9 radars, mounted low on the carrier’s sides, would be severely limited at detecting low-flying threats over the horizon.

It could also be argued that, with escort warships and F-14s already providing a robust outer defensive layer, there was not a pressing need for this same capability to be replicated aboard the carrier itself.

Still, had the Navy pursued the Sea Phoenix, the service could well have ended up with a very capable air defense system, the self-contained nature of which could have meant it would have been able to be added to existing warships fairly easily. It could have also provided a useful intermediate capability between the Sea Sparrow and other point-defense systems and the long-range Aegis system with its Standard missiles.

Nevertheless, with Aegis around the corner, the value of the Sea Phoenix’s multi-target, long-range engagement capability was reduced accordingly. Meanwhile, the Sea Sparrow also gained a multi-target capability after the introduction of multiple illuminators and full integration with the ship’s combat system. Today, the RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile is far more capable than the RIM-7, but leverages its same infrastructure.

In the event, the Navy’s aircraft carriers were left with the Sea Sparrow to protect them against close-to-medium-range threats, with outer-tier defense left to other assets. As for the Navy’s air-launched Phoenix, it was retired from service in 2004, long after the apparent demise of the Soviet cruise missile threat.

With all this in mind, the surface-launched sister missile to the AIM-54 remains little known but is certainly an intriguing case of “what might have been,” had the Navy chosen to pursue it.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com