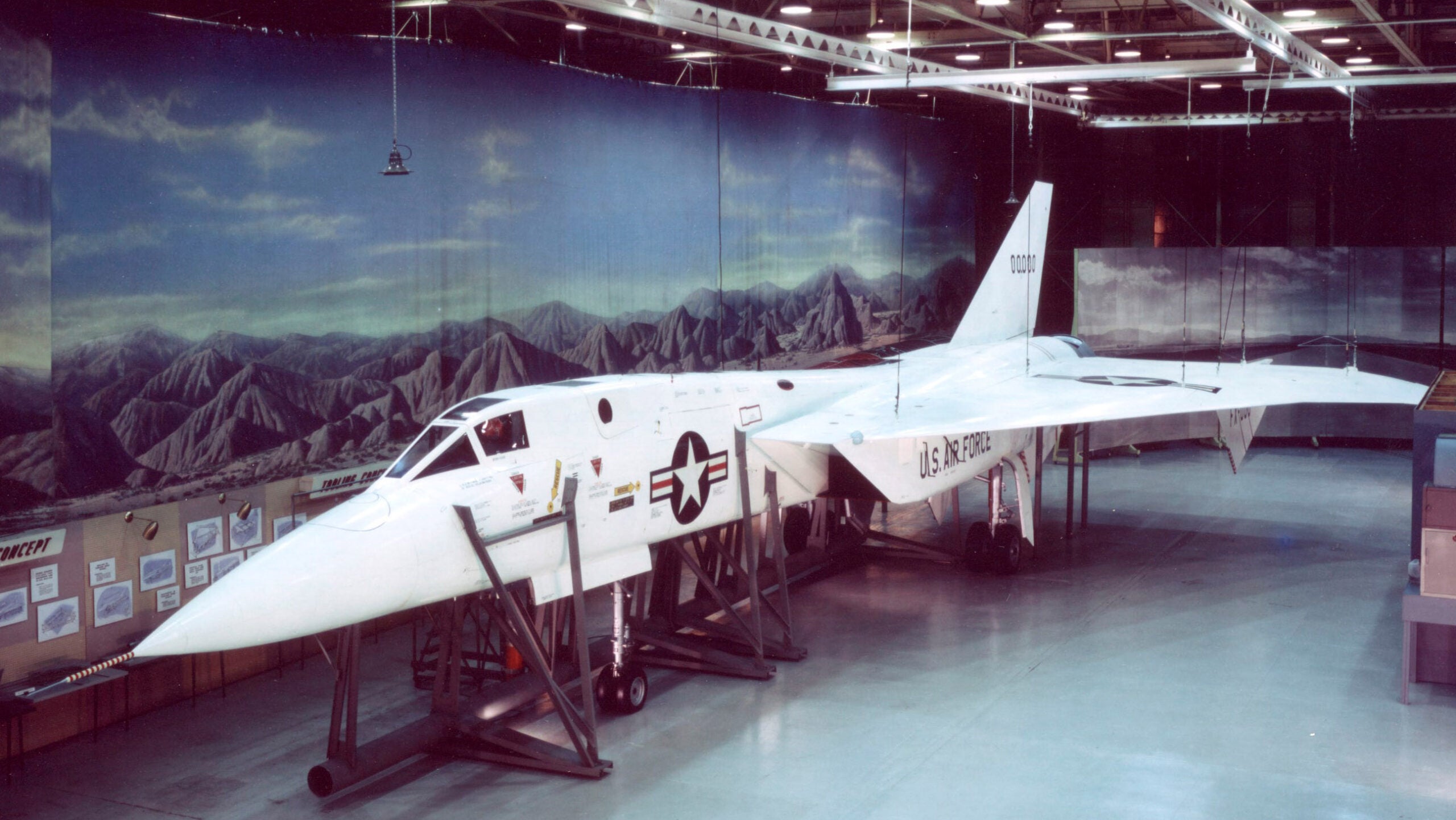

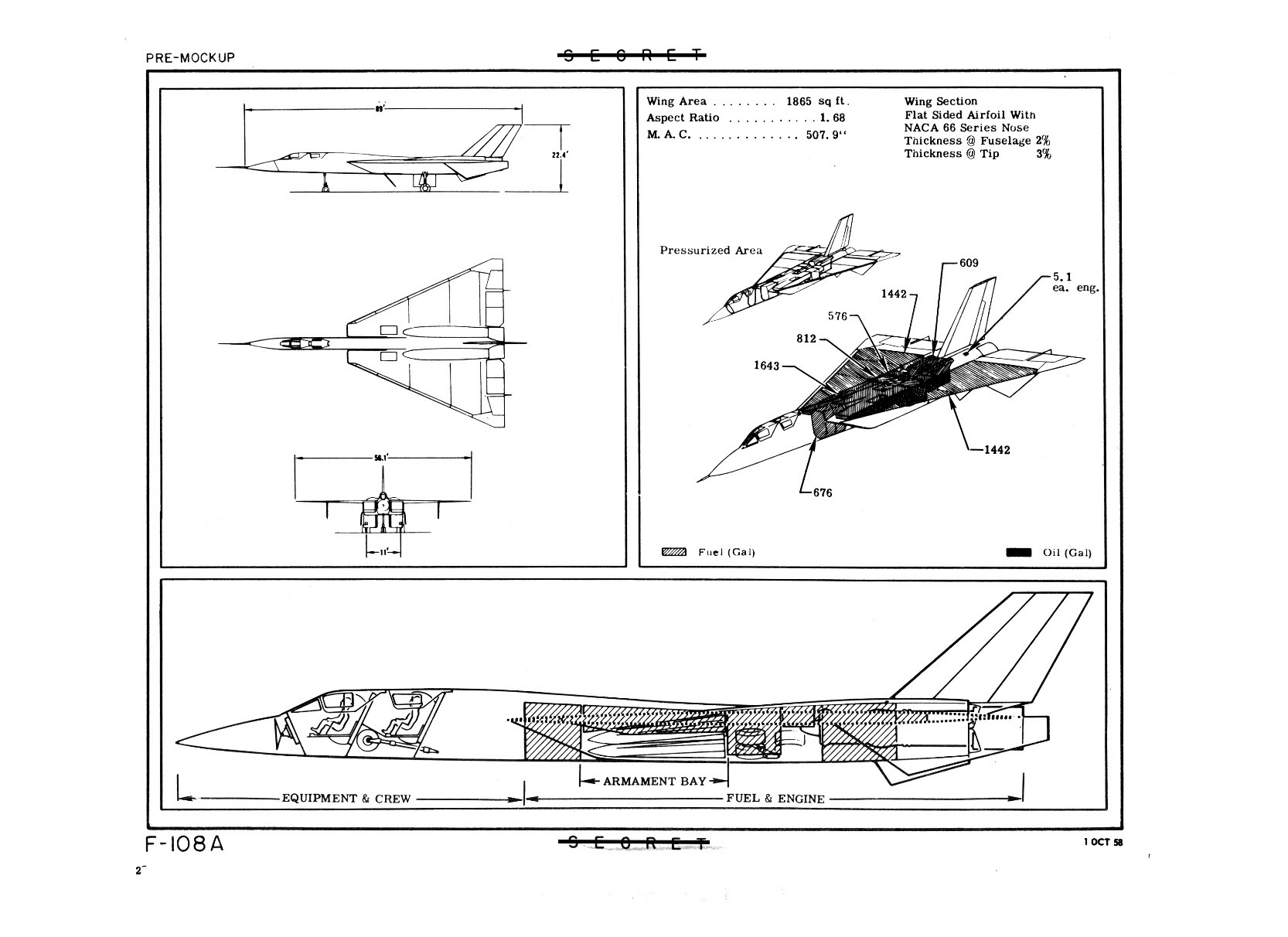

Of all the aircraft projects of the 1950s that never saw the light of day, without doubt, one of the most potentially impressive was the North American XF-108 Rapier. This was a planned all-weather interceptor that would have been propelled to a speed of over Mach 3 by a pair of General Electric J93 afterburning turbojets. Those were the same engines that powered the remarkable XB-70 Valkyrie strategic bomber, another Mach-3 North American product. The XF-108 shared some visual similarities and certain components with its larger cousin, but perhaps the most novel feature was its unique, internal rotary missile launcher.

A rotary launcher for weapons is today a standard fixture in the bomb bays on U.S. strategic bombers, but no operational American fighter has ever had a similar feature. While there have been some ingenious solutions to packing weapons into internal bays on fighters, and new technologies are still being developed in this field today, rotary launchers are much more associated with air-to-ground weapons, rather than air-to-air ones.

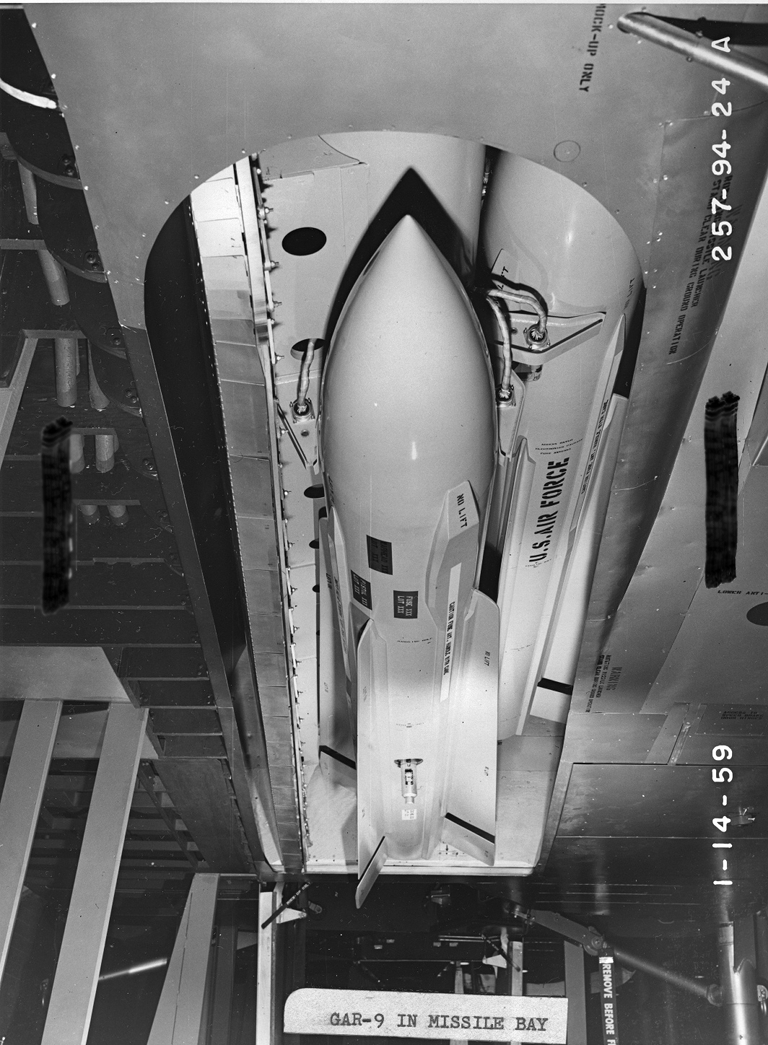

After Air Defense Command released its General Operating Requirement (GOR) 114 in late 1955, work on the XF-108 began, leading to a full-scale mockup that was presented to the Air Force in January 1959. A photo of the XF-108’s rotary launcher installation, apparently from this same mockup, was brought to our attention by Twitter user @clemente3000 and shows just how neat the jet’s weapons solution was expected to be. As it was, the Rapier would be canceled before the end of that same year.

The weapons launcher, which would have carried three of the long-range GAR-9 missiles on a T-shaped assembly, was designed to fit the relatively slim stores bay in the lower fuselage between the XF-108’s huge engines and intakes. As the weapons bay door opened, it rotated to expose the missiles, meaning there were no doors that extended into the airstream.

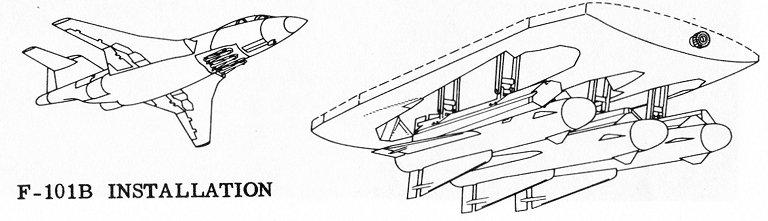

For a while, at least, the McDonnell F-101B Voodoo used a somewhat similar arrangement for its armament, with a rotary pallet that carried three Falcon air-to-air missiles on the outside, and three more on the inside, but when opened, all the missiles were exposed. On the XF-108, in contrast, a single missile was exposed in turn.

With a primary mission of swatting down nuclear-armed Soviet bombers before they got too close to American territory, the Rapier would have been expected to cruise at Mach 3 and 70,000 feet and hit an altitude of 100,000 feet in a zoom climb. Burning exotic “zip” fuel, which produced much more energy on combustion than normal jet fuel, each of its engines would put out around 30,000 pounds of thrust, a little more than the F100-PW-229 that powers today’s F-15EX, albeit optimized for high-speed, high-altitude flight. These performance expectations meant that internal weapons carriage was a prerequisite, not only to ensure low drag but because kinetic heating would likely render any external ordnance useless.

As for the missiles the XF-108 was intended to carry, the GAR-9 was a member of the Hughes Falcon family, but was considerably larger than its cousins, with a length of over 12 feet. By comparison, the GAR-1D and GAR-3A Falcons then in service at the time were around 6 and 7 feet long, respectively.

The GAR-9 had been specifically developed for the Long-Range Interceptor Experimental (LRI-X) program, for which the XF-108 was selected in 1957 as the winning design, being chosen ahead of the rival Republic XF-103.

Originally intended to carry a conventional or nuclear warhead, the GAR-9 would have had a range of 100 miles or more, flying to its target using semi-active radar homing, with the engagement process being managed by the AN/ASG-18 fire-control system on the Rapier. Design changes to the GAR-9 increased its weight and diameter, leading to modifications to the XF-108’s weapons bay, although it’s unclear if the rotary mechanism was changed in the process.

Ultimately, however, despite good progress in the development effort, XF-108 was canceled in 1959, with the Air Force failing to find the funds needed to keep the program alive, despite its promised performance. Moreover, the concern about Soviet bombers was beginning to diminish, now that intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) appeared to pose a much graver threat. It would be left, instead, to Convair F-106 Delta Darts to defend North American skies against bombers, a job that they did well into the 1980s.

A similar fate befell the XB-70, too, this being canceled in 1961 — before any examples had been flown. The reasons included developments in Soviet surface-to-air missiles, which were expected to put it at risk, as well as the appearance of cheaper, nuclear-armed ICBMs.

Despite the demise of the XF-108 program, work continued on the GAR-9, which was redesignated as the AIM-47 in 1963. It was now intended to arm the Lockheed YF-12A, the interceptor version of the A-12 spy plane, which performed several successful test launches of the AIM-47 before it, too, was canceled.

Thereafter, the AIM-47 and ASG-18 helped inform the design of the AIM-54 Phoenix and AN/AWG-9 radar that, as part of the F-14 Tomcat, ensured air defense of the U.S. Navy carrier battle groups for much of the Cold War.

While the developmental DNA of the XF-108 was destined to endure, the U.S. Air Force was destined never to field a Mach-3 fighter, let alone one armed with a revolving missile launcher.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com