China’s expansive far western regions are well-suited to hosting facilities to support various kinds of military research and development and test and evaluation activities, as well as ostensibly civilian work that could also have military applications, especially in the air and space arenas. These areas of the country, which are also highly remote, help to keep all of these activities away from prying eyes. As such, they are practically littered with notable or otherwise curious infrastructure.

One particularly interesting facility that appears to have largely escaped public attention, features, among other things, an absolutely massive hangar—you could fit a Nimitz class supercarrier inside with 100 feet to spare on either side—and is situated near other sites associated with missile defense and anti-satellite activities. The hangar clearly has to do with the development of lighter-than-air craft, which could include large unmanned airship designs capable of operating in the upper reaches of the atmosphere.

The War Zone has obtained satellite imagery of this site from Planet Labs and has reviewed additional images of the site that are available from the company, as well as through other sources. The hangar is situated just over five miles south of Bosten Lake, the largest lake in China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region. It is also located some 60 miles east of Korla, Xinjiang’s second-largest city and the capital of the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture. Malan Air Base, a secretive People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) test base with an emphasis on unmanned platforms, is notably situated on the opposite side of Bosten Lake from this hangar.

The hangar is approximately 1,150 feet long and 450 feet wide. It is also extremely tall, as is made clear in satellite images where there are ground vehicles or shadows present. An image of the site, available through Apple Maps, the date of which is unclear, also notably shows what appear to be military vehicles with overall green paint jobs, as is common to see on trucks and other vehicles in service with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

A runway-like area, which appears to be paved or otherwise partially improved, extends some 3,000 feet to the west of the hangar. As seen in the image below, there is a separate unimproved, but visibly demarcated path that extends diagonally northwest from the middle of the improved section and leads to a tower in the center of an area marked by a circle with a cross inside it.

While we can’t say with absolute certainty what the hangar’s purpose is, its general size and shape are in line with others around the world, past and present, associated with lighter-than-air vehicles, including various kinds of airships. However, it is significantly larger than many of these structures and would appear to be one of the largest aircraft hangars of any kind anywhere on Earth.

A satellite image of the site from Planet Labs, dated Nov. 25, 2020, offers additional evidence of an airship connection in that it shows the hangar’s huge door open and a big rectangular cradle positioned in front of it on the “runway.” Lighter-than-air craft cannot be moved in and out of a hangar-like regular aircraft and this piece of equipment looks like what one might expect to see for use in maneuvering a very large airship around, as opposed to more typical options, such as some sort of mobile mooring mast or mooring lines lashed to ground vehicles. The rectangle shape of the cradle could point to a non-traditional airship configuration without a largely cylindrical center structure, as well. With all this in mind, it seems highly probable that the nearby tower is a mooring mast.

The hangar may be part of a larger complex, as well. An access road connects it to a larger one that runs north toward Bosten Lake, as well as south to a number of other highly remote facilities. Some two miles to the south is a collection of buildings, including hangar-like structures with retractable roofs, some of which are camouflaged. Satellite imagery shows additional green-colored vehicles, as well as camouflage netting, further pointing to military activity. There is an additional grouping of structures even further to the south, as well.

Both of these sets of facilities feature, in part, arrays of what appear to be metal arches with squared-off edges, as seen in the images below. It’s unclear what these structures are for, but satellites images do show a large somewhat cylindrical object suspended between one pair of arches.

Past reports have suggested that much of this infrastructure, some of which predates the appearance of the airship hangar, could be related to ground-based anti-satellite laser systems, as well as electromagnetic pulse or high-power microwave weapons and testing. Some of the features visible at these sites, especially the object seen between the two arches, are in line with known U.S. military EMP-related test facilities.

A large tower is situated to the south, some four and a half miles from the hangar, as well. It is possible that this could be another mooring mast, but it seems as if it might be overly tall for this purpose when compared to historic examples of such masts. Tom Jarvis, a journalist and editor at Audio Ordeal, who appears to be one of the first to have closely explored the visible infrastructure in this area of western China, estimated it to be nearly 284 feet tall based on the shadow it cast in one satellite image. Jarvis also noted that its overall design also appeared similar to drop testing towers, such as the Fallturm in Bremen in Germany.

Looking eastward, there is one isolated hangar-like structure, as well as yet another one attached to a nearly 8,000-foot-long paved runway-like strip. Again, there are what appear to be military vehicles parked at the latter site.

A road-like extension from this “airstrip” continues eastward and then hooks south to yet another set of structures, including a trapezoidal bunker-like one. The Planet Labs image of this area on (?), seen below, shows some additional infrastructure compared to past shots, as well.

Regardless, we don’t know exactly what kind of work might be going on at the hangar, or any of these nearby sites, now, or have taken place there in the past. None of the satellite imagery The War Zone reviewed, including the Nov. 25 shot with the hangar door open, show any airships or other lighter-than-air craft of any kind.

We don’t know precisely when construction began on the hangar or when it was completed, either, but the available imagery does show that the foundation had been laid by 2013 and indicates that the full structure had been erected by 2015. An academic paper published in the Chinese Journal of Aeronautics in 2018, which was written by researchers at Beihang University and titled “Multi disciplinary design optimization with variable complexity modeling for a stratosphere airship,” mentions in passing a test of one such airship, called Tian Heng, in Korla the year before.

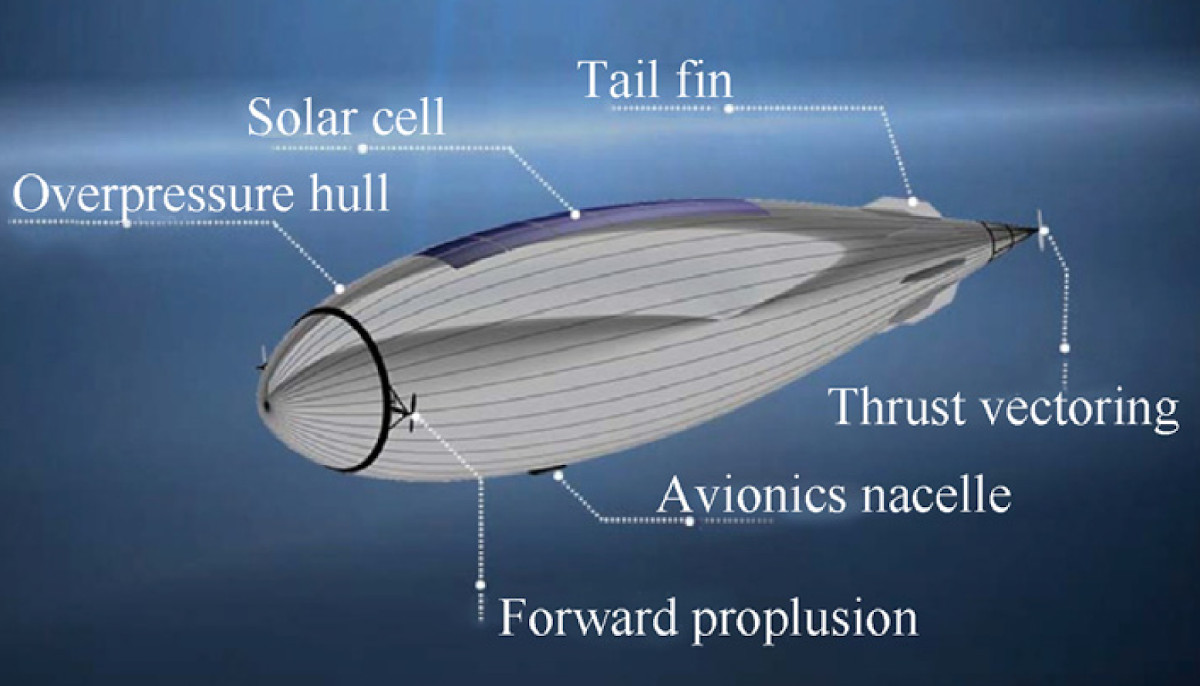

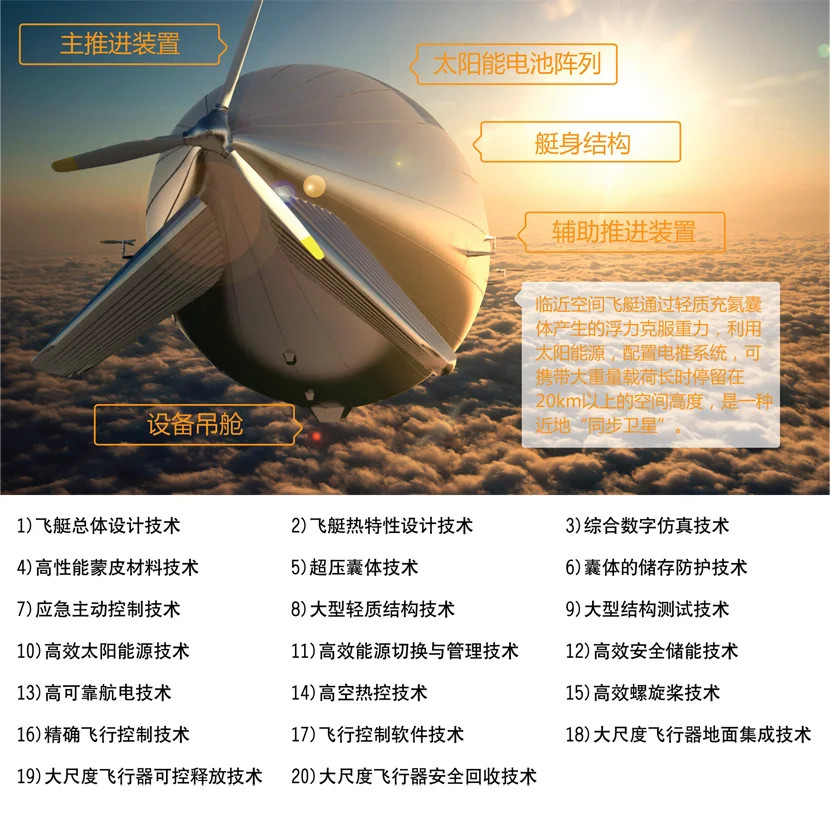

An accompanying graphic depicting the Tian Heng, seen below, shows a more complex solar-powered stratospheric airship design with two propellers at the front for “forward propulsion,” and another at the rear capable of “thrust vectoring,” which would allow for changes in direction of its flight. It is an unmanned design with an “avionics nacelle” on the underside of its “overpressure hull.” No information is given as to its size.

Neither the graphic nor the text of the paper makes any mention of specific payloads that the Tian Heng might have carried or been designed to carry. “Nowadays, a stratosphere airship sows its origins from earth observation, maritime monitoring, missile warning, communication signal relays, etc., namely, it is mooted as an affordable part substitute for a near-earth orbit satellite or can eliminate the need for multiple aircraft sorties to sustain continuous on-station keeping,” the paper’s authors noted in its introduction. The stratosphere is generally defined as beginning between altitudes ranging from 23,000 to 66,000 feet, with the measurements depending on where you are on Earth.

The paper also mentions a 2015 test of another airship designed for stratospheric operation, the Yuan Meng, but said that it took place in Xilinhot in Inner Mongolia, nearly 1,500 miles to the east of where the hangar is located in Xinjiang. That test was supposed to have lasted 24 hours in total and have taken the airship, which was 75 meters long and had a hull diameter of 22 meters, to altitudes up to 20,000 feet. It’s unclear how Yuan Meng ultimately performed.

“Using solar power to drive its rotors will save additional weight in order to increase payload, and gives it a total flight endurance of six months,” according to a piece from Popular Science at the time. “The Yuanmeng’s 5- to 7-ton payload of data relays, datalinks, cameras and other sensors would also be powered by the sun.”

With all this in mind, it is interesting to note that the hangar’s foundation appears in satellite imagery the same year that an “airship base” officially opened in Alxa League in Inner Mongolia. In 2014, Chinese media announced an impending flight test of what was claimed to be the world’s largest airship, known as the BNST-KT-02, from this facility.

“As the largest airship in the world, the BNST-KT-02, as it is known, measures 100 meters in length, 30 meters in diameter and weighs 13 tons,” according to a report from the state-run China Daily. “The gargantuan airship also has a payload of 2 tons and can reach a maximum height of between 6,000 to 7,000 meters.”

It’s not clear if that test ever occurred. The site did support other airship projects, as well, at least for a time.

Satellite imagery of the airship base in Alxa League from 2016 shows a hangar that is similar in size and shape to the one near Bosten Lake, but appears to show it in what appears to be a state of disrepair. The state of other structures at the site, as well as that of the apron in front of the hangar and other associated infrastructure, raises questions about whether this facility was ever actually completed. Another image taken of this area in November 2020 shows no new activity.

It’s also interesting to point out that Alxa League is some 640 miles southwest of Xilinhot, which is where the test of the Yuan Meng airship occurred in 2015, according to the 2018 paper in the Chinese Journal of Aeronautics. This would seem to further indicate that the Chinese ultimately abandoned plans for the Alxa League facility and moved airship research and development to other sites.

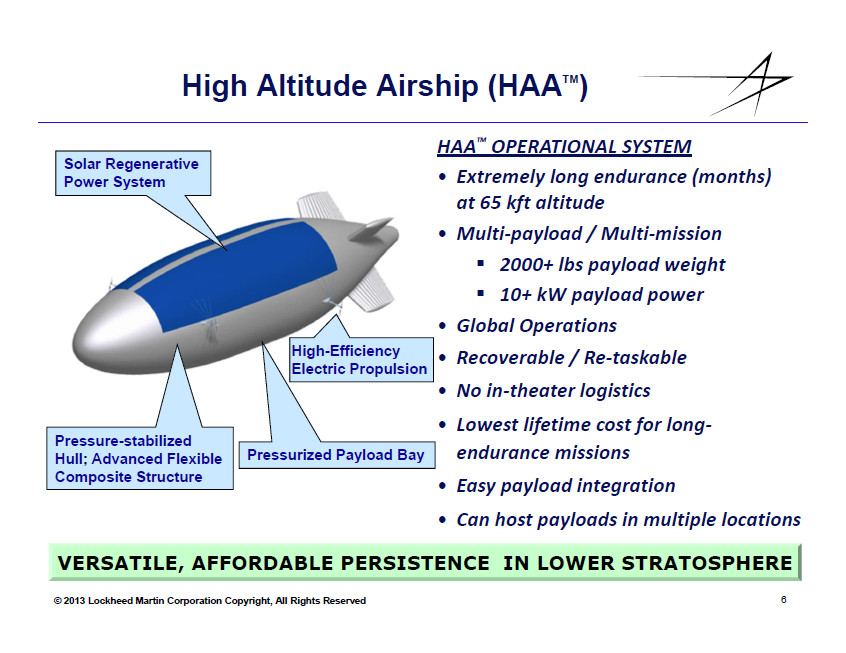

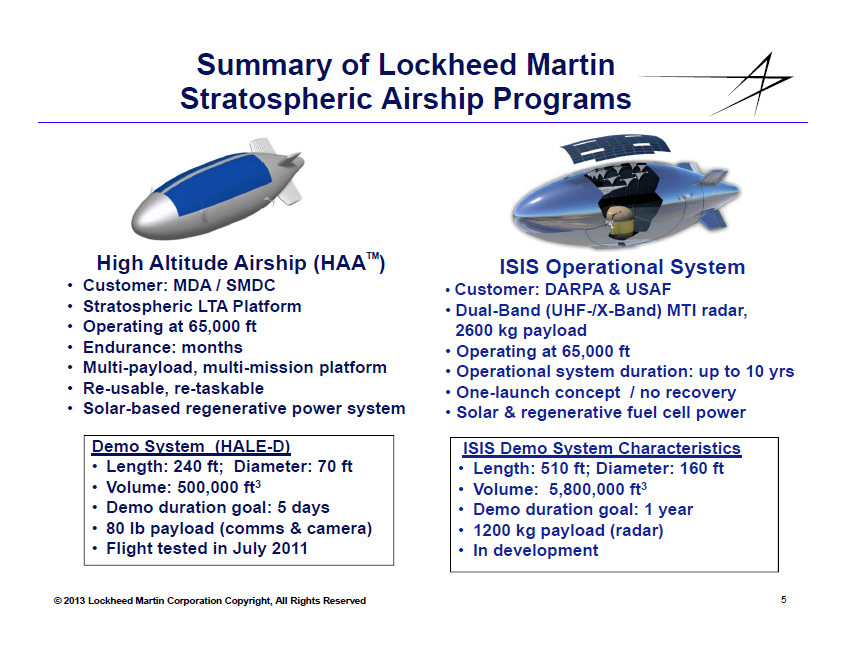

Construction of the hangar in Xinjiang also interestingly coincides with the tail end of a particularly pronounced burst of interest in lighter-than-air craft on the part of the U.S. military, including designs intended for stratospheric operation, particularly in support of missile defense missions. In 2013, Lockheed Martin was notably still actively pitching its High Altitude Airship (HAA), which the 2018 paper in the Chinese Journal of Aeronautics mentions as a specific example of another similar lighter-than-air craft that existed at the time, for both military and civilian research purposes.

At that time, the company said that solar-powered HAA could carry payloads weighing at least 2,000 pounds, as well as generate 10 kilowatts of electricity or more, all while operating for periods of time measured in months at altitudes up to 65,000 feet.

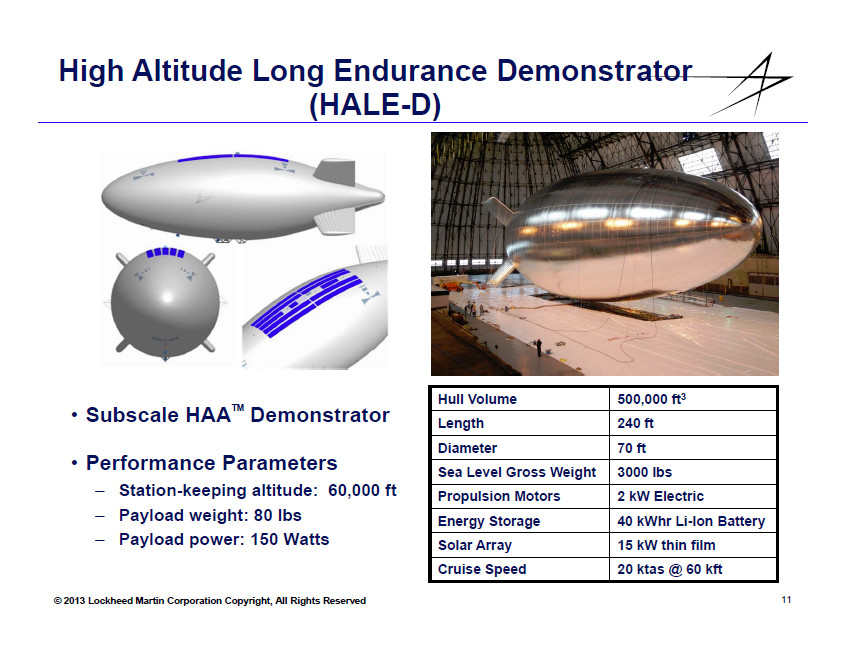

Lockheed Martin had first begun work on this airship in 2001 as part of a Missile Defense Agency (MDA) program, also known as HAA. In 2008, the U.S. Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command (SMDC) had taken over responsibility for the project, before canceling it the next year. HAA work had overlapped with the development of a subscale demonstrator for MDA, and then the Army, known as the High-Altitude Long Endurance-Demonstrator (HALE-D), as well as a separate derivative as part of an effort called the Integrated Sensor Is Structure (ISIS) that the Defense Research Projects Agency ran together with the U.S. Air Force.

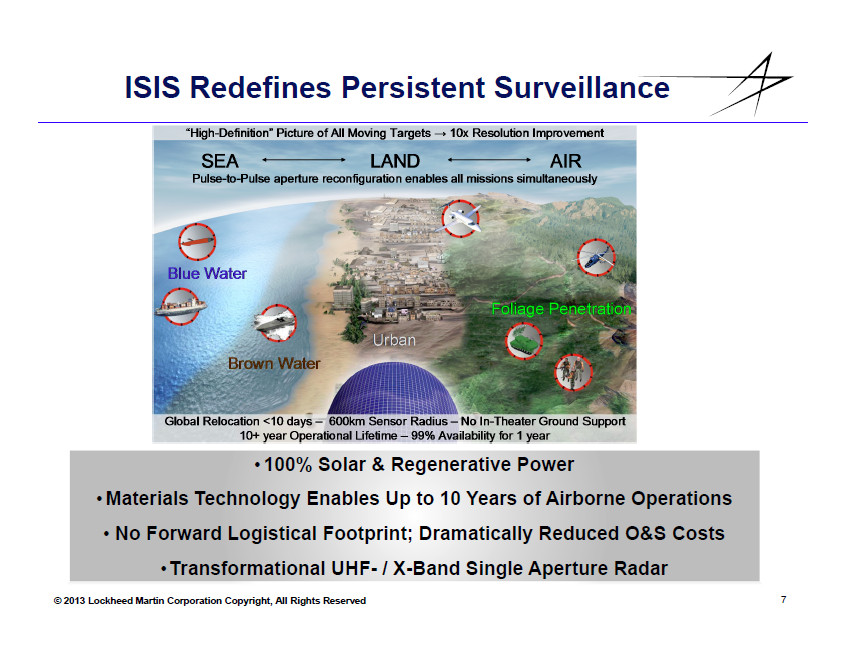

HALE-D crashed during its first test flight in 2011. The airship, including its payloads, which included full-motion video cameras and a communications package, was completely destroyed in the accident and the Army canceled the project later that year. The ISIS project, which had planned to install a dual UHF/X-band radar with moving target indicator functionality inside an HAA-derived airship, came to an end in 2014.

At around the same time, the Army’s SMDC was also experimenting with other stratospheric designs that Aerostar and the Southwest Research Institute developed together, known as the HiSentinel series, again with an eye toward missile defense applications. These are, of course, just some of the high-altitude light-than-air projects that the U.S. military, as a whole, has and still is working on to this day. Aerostar subsequently evolved into Raven Aerostar, which remains actively engaged in such work.

While we don’t know what applications any Chinese airship work at the hangar in Xinjiang may have focused on in the past, or may still be exploring now, it is very possible that it could be, or have been, at least in part, focused on missile defense. China has publicly acknowledged work on ground-based ballistic missile defenses over the years, including a test of an interceptor just earlier this year. Video footage purporting to show part of that test subsequently emerged online and was said to have been shot somewhere in the Bayingolin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture.

A stratospheric airship could provide valuable, long-range persistent radar coverage, unencumbered by the limitations imposed by the rugged, often mountainous terrain in China’s far western regions, for both testing and operational missile defense applications or other purposes. Korla is already home to a large, ground-based phased-array radar, as well as a missile test facility. The PLA’s Unit 63618, which is involved in missile defense activities, is based there, too.

A stratospheric airship, in general, could offer significant benefits as a platform for anti-missile weapons, including interceptors or directed energy weapons, such as lasers or high-power microwave generators. Fired from a very high-flying lighter-than-air craft, an interceptor would not have as far to fly in order to reach certain kinds of harder-to-reach threats, such as ballistic missiles in the mid-course portion of their flight outside of the Earth’s atmosphere. Similarly, placing directed energy weapons on such a high-altitude platform might help mitigate issues of atmospheric distortion and diffusion, which can limit the effectiveness of ground-based systems, without overly onerous power generation requirements.

It is also important to remember that many ostensibly missile defense-related capabilities are inherently applicable to anti-satellite operations, as well. As already noted, some of the other structures in the general vicinity of the airship hangar could be related to China’s research and development of anti-satellite capabilities. “In addition to the development of directed-energy weapons and satellite jammers, the PLA has an operational ground-based anti-satellite (ASAT) missile intended to target low-Earth orbit satellites,” a 2020 Pentagon report to Congress on Chinese military developments declared. The U.S. government has also accused its Chinese counterparts in the past of using reported missile defense testing as a cover for anti-satellite work.

None of this would, of course, preclude the use of such an airship for other purposes, including as a platform for other types of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) packages or as a communications relay node. A pseudo-satellite communications capability could be very valuable in any future high-end conflict, where satellites would be prime targets and where it could be difficult to quickly place new ones in orbit. This is something the U.S. military, in particular, is also grappling with.

There has also been work elsewhere on using large airships as a lower-cost method of launching payloads into space.

Any large airship hangar could also support research and development into designs not intended for stratospheric operation, including multiple smaller types, as well. At the same time, the size of the cradle seen in the satellite imagery outside of the hangar in Xinjiang would seem to point toward the hangar being primarily intended for use with a single, larger design. As already noted, the shape of that cradle could potentially point to a design with a non-traditional shape, such as a hybrid airship.

Hybrid airships typically have small wings or some other form of “lifting body” type design features, and often have squatter hulls than traditional blimps or aerostats. Various companies have pitched such designs over the years for commercial and military purposes, generally with significant emphasis on long-endurance and heavy-lift cargo capabilities. Between 2010 and 2013, the U.S. Army tested one such design, known as the Long-Endurance Multi-intelligence Vehicle (LEMV), which was designed to carry a Northrop Grumman-developed ISR payload.

British company Hybrid Air Vehicles developed the actual airship, known as the Airlander, and has continued its development work in the years since the Army program was canceled. U.K.-based Varialift Airships is one of a number of other firms also still working on similar designs.

In addition, by the mid-2010s, Lockheed Martin was still working on its P-791 design, which had lost to the Northrop Grumman proposal for the LEMV program, and it subsequently began the development of derivatives for commercial applications. Despite plans to “float out” a prototype of the new LMH-1 design in 2019, this airship still does not appear to be have been publicly unveiled.

For China, a hybrid airship design could be very useful for moving large amounts of cargo, including outsized payloads, to remote outposts inside the mainland portion of the country or on islands around the Pacific.

All told, we can’t say for sure what the purpose of this airship hangar, or any work that has been done or that might be still be going on there, might be. However, it seems very possible that it is intertwined, at least to some degree, with the missile defense and potential anti-satellite activities going on at other facilities in the immediate area. This would not only be in line with what is know about the PLA’s development of both of those capability sets, but also, as already noted, reflects work that was going on publicly elsewhere in the world, particularly in the United States, around the time the construction of the airship hangar began. At the same time, these are many other areas of interest the Chinese could have when it comes to airships.

Going forward, we will certainly be keeping a watchful eye on this highly unique and secretive facility.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com