Recent satellite imagery indicates that China may be building a large intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, field, with more than 100 silos in the northwestern portion of the country. The appearance of the site, much bigger than anything like it that China has ever built before, suggests that Beijing might be eying concept for a more survivable ICBM deterrent, in which potentially large numbers of silos are filled with only a few functional missiles, presenting enemies with a much more challenging target, should they wish to destroy it in a first strike. Intriguingly, that would echo an idea that the United States was looking to implement for its own ICBMs toward the end of the Cold War.

The apparent ICBM field was identified in satellite images of a patch of the Gobi Desert near Yumen in China’s Gansu province and was brought to wider attention by an article in the Washington Post yesterday. The original analysis came from the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and is based on imagery provided by private firm Planet Labs.

According to those researchers, the evidence, so far, reveals that construction has begun on at least 119 silos, over an area of more than 700 square miles, which would represent a significant expansion of the country’s strategic nuclear firepower. Until now, the country’s non-mobile ICBMs have been limited to around 18 silos for DF-5A and DF-5B missiles, also referred to by the U.S. government as the CSS-4 Mod 2 and CSS-4 Mod 3, respectively. The latter type carries a number of multiple independent reentry vehicles, or MIRVs. There have also been reports that the Chinese might be developing an improved DF-5C missile, as well as a silo-based version of their new DF-41 ICBM, which U.S. officials also call the CSS-X-10.

As well as the new silos, a close examination of the Yumen site by the U.S. researchers at the James Martin Center has revealed apparent construction of underground bunkers, cable trenches, roads, and a small military base.

“We believe China is expanding its nuclear forces in part to maintain a deterrent that can survive a US first strike in sufficient numbers to defeat US missile defenses,” Dr. Jeffrey Lewis, an expert on missiles and nuclear weapons at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies told the Washington Post. It is notable that China is one of the few, and perhaps even the only nuclear-armed power to have declared no first use policy.

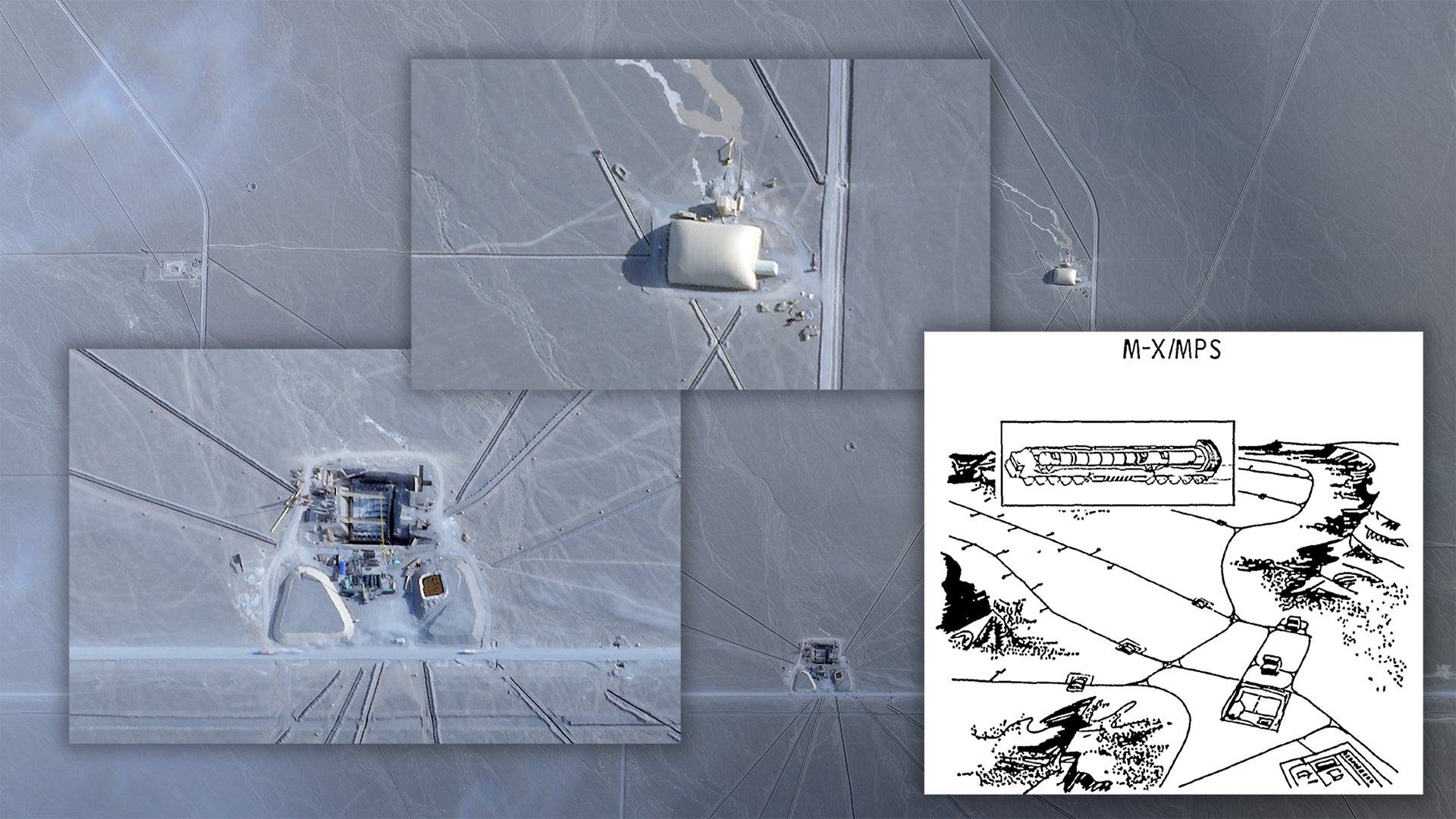

A potentially intriguing aspect of the construction is that the thinking behind it could be revisiting America’s Cold War-era ‘shell game’ concept, in which a significant number of silos would be built, but only a few of them would be actually loaded with ICBMs. This would leave opponents unsure of where the missiles actually were at any point, forcing them to target every silo if they hoped to destroy all of the missiles before they were launched. This, in turn, would sap an enemy’s resources during any exchange, without having to actually procure and maintain large numbers of ICBMs, to begin with.

Under the original U.S. plans, dating from the late 1970s, 200 examples of the proposed MX ICBMs (which ultimately evolved into the LGM-118A Peacekeeper) would have been transported around oval ‘racetracks,’ each around a dozen miles long, and each provided with 23 underground shelters where the weapons could be hidden from spy satellites. The situation for the potential enemy would have been made more complex by interspersing the real ICBMs with dummy missiles.

U.S. officials estimated that, to ensure the entire complex and every missile was destroyed, the enemy, then the Soviet Union, would have to expend a staggering 4,600 warheads. The original U.S. shell game concept would have also included anti-ballistic missile (ABM) interceptors, as well as ICBMs, to provide an additional degree of protection for the site and to force the Soviets to use more than one warhead against each individual target if they were to be sure of its destruction.

The shell game was just one of a large number of potential MX basing concepts that were explored, which also included mobile launchers on trains and mobile or fixed ones in buried trenches. In the end, however, the United States chose to field the MX Peacekeeper missiles in more traditional silos. A succession of arms control agreements with the Soviet Union and then Russia ultimately led to the early retirement of the LGM-118As, with the last of them withdrawn from service in 2005.

“While it might seem that 120 silos means 120 missiles, it could very easily be 12,” Lewis told Foreign Policy, referring to the potential Chinese shell game. “We just don’t know. And even if China were to deploy only a handful of missiles, its forces could over time grow into the silos. Yet whether the number is 12 or 120, this is an alarming development.”

The possibility of Beijing adopting the shell game approach seemed to be echoed by John Culver, a retired CIA analyst on East Asian affairs, who pointed to the close proximity of buildings at the site. “Grouped so closely they situationally almost dare an adversary to think about counterforce attack,” he tweeted. A counterforce attack is one directed against targets of military value, such as ICBM silos, or strategic bomber bases, with the aim of destroying an enemy’s nuclear weapons before they can be launched in turn.

A shell-game type of ICBM deployment could make sense for China, which, with an estimated 250 to 350 nuclear weapons, has far fewer than the United States or Russia. Beyond the potential cost savings from only having to build a relatively small number of actual IBCMs, keeping the silos in relatively close proximity would also make things cheaper and more straightforward in terms of maintaining command and control over the site and general logistics.

Adding ABM systems to the shell game could also be an attractive option for China, which is already busy developing these types of weapons. Seeding doubt in the minds of rival powers’ war planners would also be in line with the Chinese government’s policy of ambiguity around how its existing nuclear forces are postured.

Some experts and observers have raised the possibility that the entire desert silo complex could actually be part of an elaborate ABM system, similar to the controversial U.S. Ground-based Midcourse Defense missile defense system, or GMD, rather than housing ICBMs, at all. However, the site’s general location would seem to be less than optimal for this use, especially given the likely approach trajectories of incoming threats from the United States.

However, if the new silos are primarily related to ICBMs, it would also seem to tally with previous Pentagon assessments regarding increasing numbers of Chinese warheads, ICBM silos, and a change in deterrence posture. According to last year’s Annual Report to Congress on Chinese military and security developments: “New developments in 2019 […] suggest that China intends to increase the peacetime readiness of its nuclear forces by moving to a launch-on-warning (LOW) posture with an expanded silo-based force.”

Launch-on-warning involves ordering a ‘retaliatory’ nuclear strike by launching missiles when an incoming nuclear missile attack is detected, but before any of the incoming warheads have actually detonated. A LOW posture would be bolstered by further development of silo-based forces, as well as more survivable mobile delivery systems, but would also require the establishment of more robust enhanced early warning capabilities.

Last year’s Pentagon report on China to Congress also indicates the U.S. military believes that China may be considering additional DF-41 launch options, “including rail-mobile and silo basing.” The DF-41 might therefore be one of the more likely options to be fielded at the new ICBM site. It’s thought that this missile might already have been tested from an ICBM silo in 2019, with a test site near Jilantai in the west of the country “probably being used to at least develop a concept of operations for silo basing this system.”

There are also reports about the DF-41s being MIRVed and an expanded silo-based MIRVed ICBM force would likely be among the factors driving the U.S. Department of Defense assessments about China looking to significantly expand the number of deployed warheads it has.

On the other hand, the aforementioned Annual Report to Congress also notes that there are some indications that China may also be building new silos for the DF-5 ICBM that’s already in service in this capacity. Compared to the solid-fuel DF-41, the older DF-5 is a liquid-fueled weapon and therefore less suitable for the LOW posture. Unlike solid-fuel missiles, ones that use liquid fuels, which generally contain very caustic chemicals, typically cannot stay in a ready-to-launch state for protracted periods of time, and are only fueled right before launch, which could be too long process to work through reliably in the face of incoming nuclear strikes.

The latest development near Yumen comes amid worsening relations between China and the United States and warnings about the speed at which Beijing’s growing nuclear arsenal.

However, analysts have also urged caution against alarmism over the new ICBM field. “There are lots of reasons to question whether China is about to expand its nuclear arsenal this rapidly, although it is expanding it a bit,” said James Acton, a co-director of the nuclear policy program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Lewis, meanwhile, also pointed to the influence on China of U.S. developments in the fields of new types of nuclear weapons and delivery systems, including air-launched cruise missiles, new warheads for submarine-launched missiles, as well as updated missile defense systems. “We’re stumbling into an arms race that is largely driven by U.S. investments and missile defense,” he warned.

The new missile field is certainly broadly in keeping with previous predictions about China’s expanding nuclear armory, and in particular its aims to modernize the silo-based element of its ICBMs. Overall, however, it’s too early to say what China plans to do with its additional 100-odd ICBM silos, and how they might fit into its wider strategic thinking.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com