The Air Force Research Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate has released a report detailing how the U.S. military is preparing to develop spacecraft and concepts of operations for missions beyond traditional orbits that could span all the way to the space surrounding the Moon. While the document doesn’t offer any specifics in terms of how the U.S. military might be planning to project power in space or protect its space-based assets, it does highlight the complexities that the U.S. Space Force will face as it expands into the uncharted territory of operating beyond Earth’s orbit.

The report, titled “A Primer on Cislunar Space,” was written as a guide for military space professionals to help them better understand what cislunar space actually is and how they can better develop operating concepts and relevant capabilities for this relatively new area of operations. Because traditional Space Domain Awareness (SDA) systems were designed for geosynchronous orbits much closer to Earth, future operations beyond this region of space will require entirely new models for planning and tracking the trajectories of satellites or other craft.

Air Force Colonel Eric Felt, director of the Air Force Research Laboratory’s (AFRL) Space Vehicles Directorate, told SpaceNews recently that operating spacecraft in this area of space “poses unique challenges,” but that “as commerce extends to the Moon and beyond, it is vital we understand and solve those unique challenges so that we can provide space domain awareness and security.”

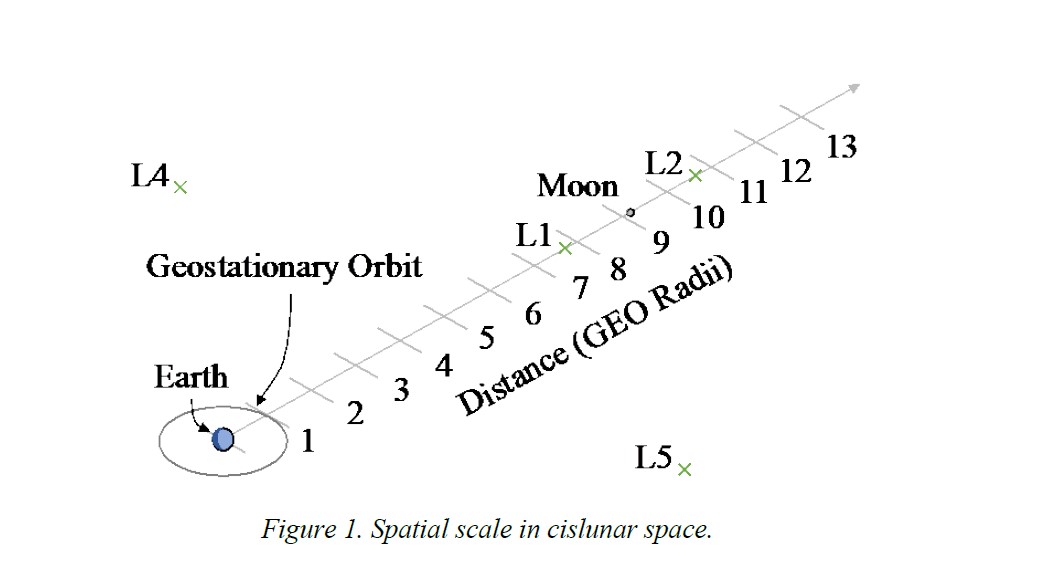

Cislunar space is generally defined as the area between Earth’s atmosphere and the Moon, which orbits the Earth at an average of 238,855 miles away in a slightly elliptical, or oval-shaped orbit. Cislunar space covers some 1,728 times more volume than what is found within one geosynchronous orbit radius, or 1 GEO. As the report notes, expanding from orbits closer to the Earth into this much larger region of space means that military and civilian space agencies have to alter their “intuition and sense of distance and time” and “further expand the volume of space [they] consider when discussing cislunar topics.”

The primer document goes into immensely technical detail about why this area poses new challenges, but it is best summed up in more general terms by its statement that “motion in cislunar space is highly chaotic,” meaning that “even the slightest deviation in the object’s current position or velocity could cause very large differences in its future propagated position and velocity.”

It’s not just trajectory calculations that are vastly different in cislunar space as opposed to in geosynchronous orbit. As AFRL’s report points out, the vastness of this new space frontier means “there is no single sensor location that can observe all cislunar space.” Because the motions and locations of the Sun, Earth, and Moon create gaps in coverage for both electro-optical (EO) and radiofrequency (RF) sensor systems, AFRL identified the need for a “collaborative network of sensors” to ensure continuous coverage in cislunar space.

Even ground-based sensor systems have a difficult time tracking objects in cislunar space, the report notes, due to the enormous distances it covers, and because the differences in relative motion between the Earth and objects in this area make it difficult to detect objects so far from Earth:

As the objects get farther from the observer, they will naturally get fainter (both for EO as well as RF sensors) and thus will put a strain on remote sensing capabilities to the point of potentially being undetectable entirely. Also, cislunar objects will generally have much longer orbital periods than GEO, thereby creating the need for more observations to cover significant fractions of orbits. One further challenge, specific to near-Earth EO sensors, is not being able to look near the Moon due to its reflection of sunlight (i.e., albedo).

To attempt to better understand this space and how to operate within it, AFRL has previously developed spaceflight experiments known as the Cislunar Highway Patrol System, or CHPS, designed to demonstrate “foundational space domain awareness capabilities in the cislunar regime” by testing object detection and tracking in this new frontier. AFRL’s Colonel Felt stated in 2020 that CHPS is merely the first step in the laboratory’s attempt to grasp domain awareness in cislunar space, and that it is “also starting to explore basic science and technology in autonomy, on-orbit processing, and logistics in all orbits, which become even more important the further you are from the Earth.”

Space Force has also turned to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) for help in better understanding cislunar space and how to operate within it. Specifically, a memorandum of understanding signed in 2020 between NASA and Space Force stresses the need for the two organizations to work together to develop new operations that can cover a much larger distance including cislunar space:

Until now, the limits of that mission have been in near Earth, out to approximately geostationary range (22,236 miles). With new U.S. public and private sector operations extending into cislunar space, the reach of USSF’s [U.S. Space Force] sphere of interest will extend to 272,000 miles and beyond – more than a tenfold increase in range and 1,000-fold expansion in service volume. USSF now has an even greater surveillance task for space domain awareness (SDA) in that region, but its current capabilities and architecture are limited by technologies and an architecture designed for a legacy mission.

AFRL’s new “Primer on Cislunar Space” and initiatives like CHPS show that even as the Space Force and Department of Defense (DOD) plan to expand military operations into farther reaches of space, even beyond traditional orbits, it still remains largely unknown what warfare operations in space will look like. It’s also unclear what particular technologies will be needed to protect American assets in Earth’s orbit and beyond, despite the fact that the Space Force already has units devoted to “orbital warfare.”

The Air Force has even run internal competitions to explore new concepts for military activities in new non-traditional orbits, including very-low Earth orbit and cislunar space. “We in AFRL are working on technologies to expand space domain awareness above the GEO belt – so from the GEO belt all the way to the Moon and even a little bit beyond,” Felt stated at the time. “It’s what we call the xGEO, or the cislunar, area of operations. And as commercial people move there, and our adversaries move there, that becomes an area where we need to know what’s going on up there.”

Even with the uncertainties of what it would actually look like, it’s clear DOD leadership is expecting to wage warfare in space. At the recent Defense One Tech Summit held on June 22, the AFRL’s Colonel Felt offered a very hopeful sentiment about how this potential war could take shape, stating:

Space war is going to look a lot like the Cold War in a couple of different ways… First of all, we hope nobody’s actually exchanging destructive weapons with each other and that we don’t just hope, but we take active actions to deter that from happening. The nature of conflict in space is that there is an offensive advantage, or a first-mover advantage, in that it is a lot easier to attack somebody else than to defend your own stuff. And we’ve seen that before—that’s the same as with…nuclear weapons.

Colonel Felt’s optimism about not getting to the point of exchanging destructive weapons may be misplaced, considering our peer adversaries in space are preparing for just that.

The United States isn’t the only nation eyeing to expand into new frontiers in cislunar space, and the potential for threats emanating from this region has been raised by actual US military officials in the past publicly. China is rapidly expanding into this area of space, prompting some concern that America’s satellites in geosynchronous orbit, including early warning sensors, could be “stabbed in the back” in the event of a conflict, which we sounded the alarm about in this past feature of ours.

While it would take a threat originating from cislunar space days to reach satellites or other assets in orbits closer to Earth, it could also be that there are adversary capabilities there that we aren’t aware of that could carry out attacks on American satellites and other craft in the same region relatively rapidly and undetected. The growing concern among the DOD seems to be that it has no sense of what’s going on out there, hence the need for the Cislunar Highway Patrol System and other sensor systems capable of monitoring this region of space.

“We’ve seen [reports] in open press…that say the Chinese have a relay satellite flying around…the flipside of the moon. That’s very telling to us,” said Jeff Gossel, senior intelligence engineer in the Space and Missile Analysis Group at the Air Force’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center, at an Air Force Association event in 2018. “You could fly some sort of a weapon around the moon and it comes back — it could literally come at [objects] in GEO…and we would never know because there is nothing watching in that direction.”

It’s no wonder, then, that DOD leaders like former Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson have previously stated that a “show of force” might be needed to deter adversary nations from attacking or tampering with America’s space-based assets. “That capability needs to be one that’s understood by your adversary,” Wilson said in 2019. “They need to know there are certain things we can do, at least at some broad level, and the final element of deterrence is uncertainty. How confident are they that they know everything we can do? Because there’s a risk calculation in the mind of an adversary.”

That sentiment has been echoed by other top DOD officials more recently. “It’s important for your adversary to know a lot about what your capabilities are,” the AFRL’s Colonel Felt said this week. “Whereas if you keep everything secret, they might think that they can take a gamble and win with a first strike.”

Kelly D. Hammett, director of AFRL’s Directed Energy Directorate, speaking at the same conference as Colonel Felt this week, had a more definitive statement about the Space Force’s and DOD’s role in protecting American space assets. “If you look at the National Space Strategy that was signed by the Trump administration in December…it actually commits us—commits the Space Force and the Department of Defense—to…monitoring what’s going on out there,” Hammett said. “And if somebody is a bad actor in the international realm: to monitor, detect, and respond.”

The uncertainties surrounding space-based warfare are compounded by the fact that many of the Space Force’s and other American space capabilities remain classified. The DOD has previously been coy about even admitting the very existence of some space assets. It remains unknown how the military plans to respond to the potential destruction or disabling of of space-based assets that “don’t exist” at all and which the public might not even know about if the Pentagon doesn’t bring it up. To compound the uncertainty, there still seems to be ambiguity about even the most basic definitions of conflict in space.

With all this in mind, the recent AFRL’s Primer on Cislunar Space shows that all of these uncertainties will have to be addressed in the near-term as the U.S. military expands its operations into the vastness of space between Earth and the Moon.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com