A U.S. Navy research document from 2010 outlines the Naval Surface Warfare Center (NSWC) Carderock Division‘s efforts to create a working design of a manned vehicle capable of both airborne flight and submerged travel. The craft was intended to provide stealthy transport for Special Forces units into and out of operating areas. This wasn’t the first study of its kind to propose such a “transmedium” vehicle, defined as one capable of operating in multiple domains, such as in the air and underwater, but building such a craft has proven itself time and time again to be difficult, to say the least. It’s not clear how far the Navy’s efforts went, but the document’s conclusions are significant in that they show that over a decade ago, Naval researchers concluded that a “working design is feasible within the current state of the art.”

Aircraft that could also operate under the sea have long been pursued by the U.S. Navy and other militaries. A number of often unworkable or heavily compromised designs have been proposed and even tested by armed forces around the world since at least the 1950s, including various forms of submersible aircraft, to more modern designs like the short-lived Lockheed Martin Cormorant. While the degree to which these designs have been able to operate in both the sea and air environments vary greatly, among the “holy grails” of aerospace research is a truly hybrid vehicle, a submersible aircraft or “flying submarine” that can travel near-seamlessly between the sky and the sea.

In 2010, NSWC Carderock published its study of just such a vehicle concept. The idea was to research the feasibility of designing a vehicle that combined “the speed and range of an airborne platform with the stealth of an underwater vehicle by developing a vessel that can both fly and submerge.” The ultimate goal was to work towards developing a vehicle that could insert and extract Special Forces units at much greater ranges and speeds than existing platforms at the time, and be able to do so in locations that were “not previously accessible without direct support from additional military assets.” There have been far less ambitious boat-submarine concepts brought to life as of late, that try to address the issues of getting around the inherent limitations of existing swimmer delivery options. But the technological chasm between creating a vehicle that can transition between the surface and subsurface of the ocean and creating a true flying submarine is absolutely massive.

The study was born out of a Broad Area Announcement (BAA) issued by DARPA in 2008 calling for design proposals for such a Special Forces vehicle and defining a Concept of Operations (CONOP) for potential designs. NSWC Carderock based its study off of that CONOP, which outlined the need for a vehicle whose capabilities included:

– Deployment from a naval/auxiliary platform;

– take-off from the water surface and transit 400 miles airborne, then land on the water surface;

– submerge and transit 12 [nautical miles] underwater before deploying Special Forces;

– loiter for up to 72 hours fully submerged;

– retrieve Special Forces whilst submerged before transiting submerged to 12 [nautical miles] off the coast, take-off and return 400 miles to the mother ship

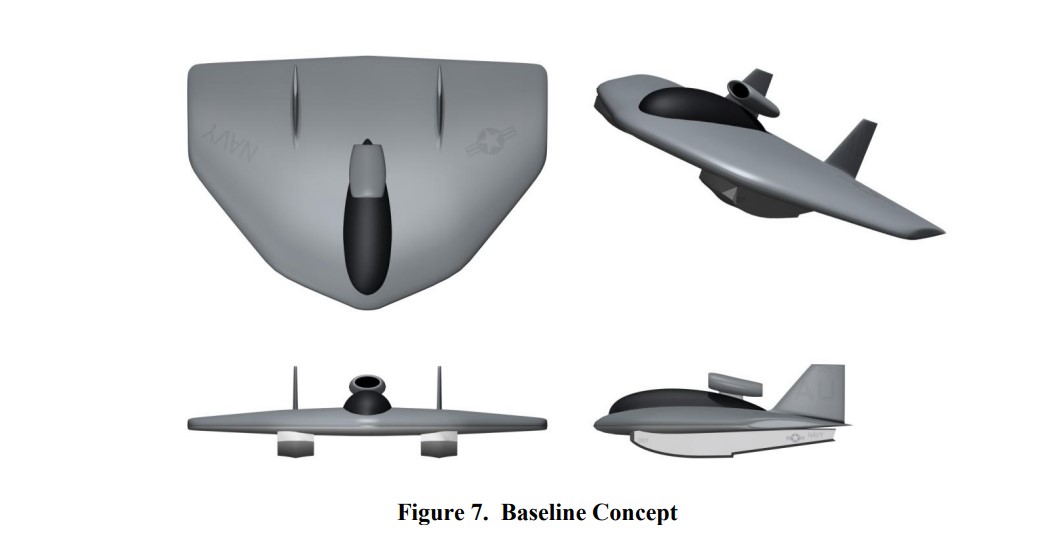

To meet that need, NSWC Carderock and the Office of Naval Research conducted a study that would determine the feasibility of building a manned triangular, “submersible aircraft” that could insert Special Forces operators “covertly at a higher speed and more independently than is currently achievable.”

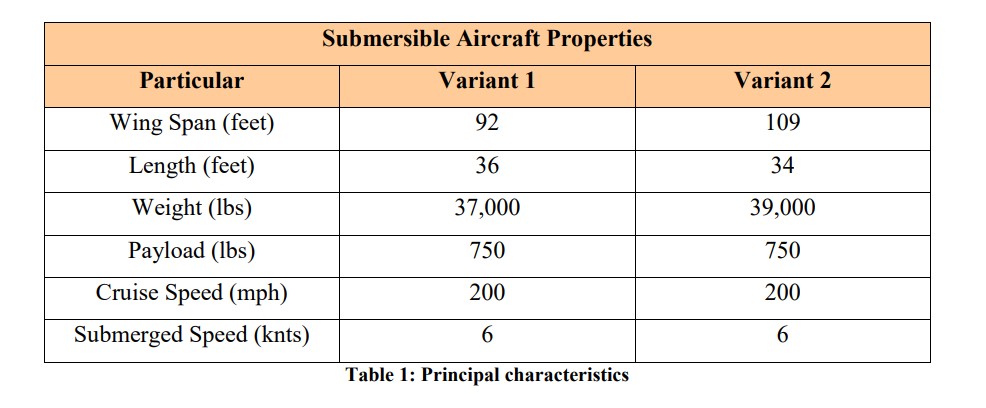

NSCW Carderock came up with two blended wing-body/flying wing-type designs for their submersible aircraft concept, one with a wingspan of 92 feet, and another with a wingspan of 109 feet. Aside from differences in size, both designs had fairly similar specifications in terms of payload, speed, and weight:

The submersible aircraft was designed to be operated by a crew of two, with room to accommodate six more Special Forces personnel for transportation. When underwater, the craft would have an operating depth of 30 meters and a speed of 6 knots; in the air, the craft would reach 200 mph.

Propulsion was an obvious challenge the study considered, and the authors note that “It quickly became apparent that turbofans, turbo-props, and pulse jets systems should be considered in more detail.” In the end, based on fuel considerations and each propulsion methods’ ability to be sealed when underwater, it was decided that the best propulsion choices were “twin turbofans within sealable nacelles for air and sea-surface operating modes,” while “a single drop-down electrically driven thruster” was chosen for submerged operations.

In order to assess the feasibility of the overall concept, a scale model with a six-foot wingspan powered by two 11-volt motors was constructed for testing. In flight tests, the vehicle displayed “very good directional stability” despite its lack of vertical stabilizers, which designers thought would severely limit the aircraft’s yaw control. The craft lost control only once during testing due to high winds, but this “was not believed to be a significant problem as the scale velocity of the wind was high,” meaning a full-sized aircraft would not have been affected as much as the small scale model was.

When floats were attached to the scale model aircraft for water testing, its designers encountered difficulty in maintaining directional control. As a result, the study notes, “Attempts made to reach take-off speed and carry out a short take-off and landing were unsuccessful.” The failure was attributed to the inaccurate alignment of the model’s floats and the “inherent flex” of the Velcro used to attach the floats. Despite the failures, the report concluded that the tests validated the concept for the transmedium vehicle’s design and made plans to address the flaws in subsequent designs and tests.

While it’s unknown if the study led to any further testing or development, the submersible aircraft study conducted by NSWC Carderock reached several conclusions, including that “feasible vehicle concepts can be generated using current technology and materials” and that “a hybrid flying wing/blended body design offers a viable solution” for transmedium vehicles and “offers a practical compromise between performance in flight, on the surface and when submerged.”

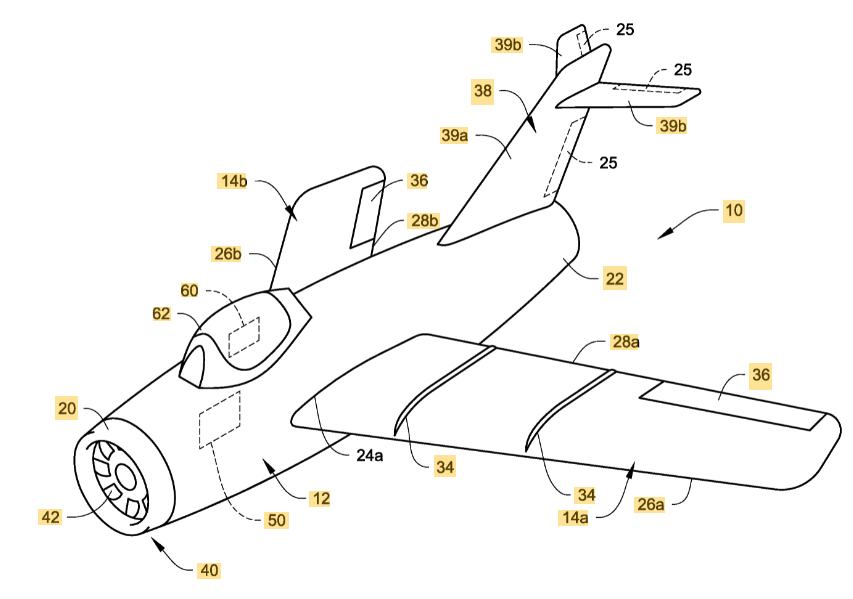

Other concepts were created in response to DARPA’s BAA for a submersible aircraft and were published in aerospace academic publications throughout the early 2010s, like the submersible airplane design seen below.

NSWC Carderock wasn’t the only laboratory pursuing transmedium vehicle research at the time. The Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) was also testing small, air-launched unmanned vehicles that could dive into bodies of water and travel short distances underwater in the early 2010s. According to a study published in 2014, these “vehicles demonstrated mixed-mode operation through dozens of swim tests and three flight tests,” although the study never accomplished air to underwater operation in a single test. The Office of Naval Research (ONR) also developed at least one such vehicle, the Flying Sea Glider, that was designed to be dropped from as high as 30,000 feet before gliding above the water and finally diving beneath the surface.

In 2018, a DARPA-sponsored research project conducted at North Carolina State University reported a “seabird-inspired fixed-wing hybrid UAV-UUV system” that successfully conducted both air flights and submerged operations that demonstrated “egress from water, flight in air, ingress into water in each flight, and water locomotion.”

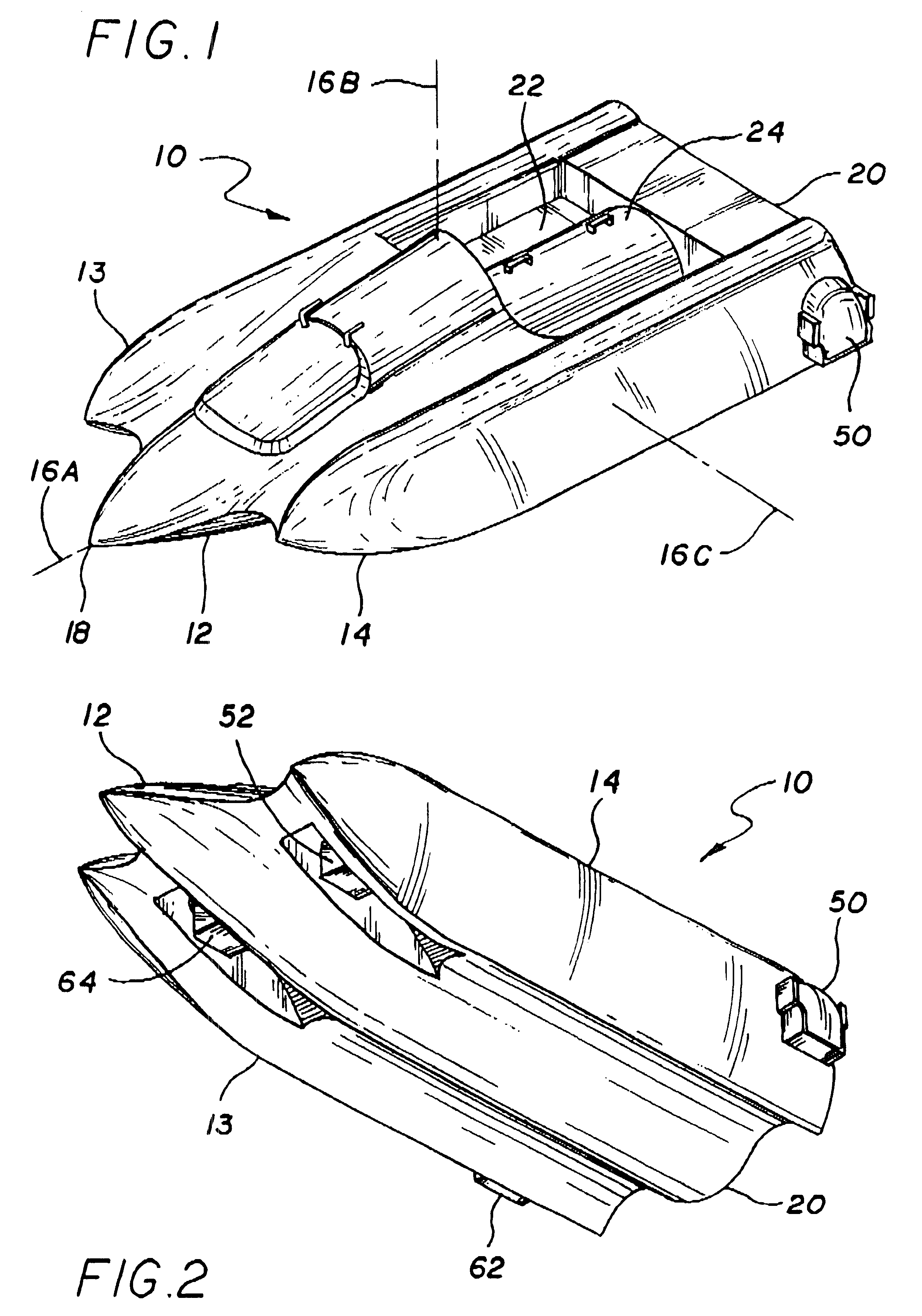

In addition to Department of Defense-funded laboratories, there has been a clear, demonstrated interest in multi-medium vehicles by the military-industrial complex. Large aerospace contractors likewise possess patents for transmedium vehicles, such as the curiously low-key name “Vehicle” patent assigned to Lockheed Martin. The “Vehicle” patent describes a turbofan-powered vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) craft “capable of travel on the water, vertical flight, and hovercraft type operation.” One of the primary purposes of the patent was to provide a VTOL vehicle capable of traveling long distances on the water.

Lockheed Martin also developed and patented the Cormorant, a stealthy, jet-powered drone that could be both launched and recovered by submerged submarines and carry a 1,000-pound payload in its modular bay. The Cormorant’s design was informed specifically by Navy specifications for unmanned aerial vehicles that could be launched by its converted Ohio-class guided-missile submarines (SSGN) at depths up to 150 feet. You can read all about Cormorant and the Navy’s ability to launch flying drones from submarines in this past feature of ours.

Like so many other transmedium vehicle projects, it’s unclear just how far the Cormorant project went after DARPA canceled the project in 2008. However, Lockheed Martin filed a patent for a separate transmedium vehicle a year later described as being able to “float in a body of water, or submerge itself underneath the water, and then later launch from the water without human intervention to perform a flying mission.”

So far, there is no hard evidence that the decades-long search for a true hybrid aerospace-underwater vehicle has resulted in anything but a trove of conceptual studies hidden away in academic literature and a handful UUV/UAV concepts that have shown promise in testing. The full-scale development of such a craft either went dark or never went much farther. Still, the fact that a Navy study concluded over a decade ago that such a concept was “feasible within the current state of the art” shows just how close we may be to seeing the dream of a submersible airplane finally realized.

Considering the tactical issues facing the U.S. military and the rise of peer state competitors like China, especially in regards to its anti-access umbrella and the long distances that would be involved in a war in the Pacific, such a vehicle would be far more relevant now than in the last few decades. A low-flying, somewhat low-observable craft could convey special operators through contested airspace and then deliver them into outright enemy territory while submerged. It’s not like the special operations community hasn’t delved into exotic infiltration capabilities before.

With all that being said, and considering the generous and far more agile budget the special operations community has, it wouldn’t be outside the realm of the possible that a concept like this is indeed in some form of development or could even exist in a clandestine operational state today.

The enemy certainly would have a hard time even figuring out what the heck they were looking at if they ran into one.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com