In early June 2019, a buzzworthy headline about an anomalous ladybug swarm swept through the news cycle. According to the story, National Weather Service radar detected a massive bloom originating out of the Mojave Desert before heading south over Southern California. The story went viral on social media before generating headlines around the world in major news outlets. Despite the plethora of coverage, it seems there was actually scant evidence that the ladybug swarm even existed at all. In fact, based on our investigation, the ladybug swarm seems to have been entirely a figment of the media’s creation, based on a single Tweet, which itself was based on a single volunteer weather observer’s report of seeing “specks” in the air. When all of the facts of the case are examined closely, the “ladybug swarm” actually appears to likely have been the result of military testing and training in the area, not a super swarm of bugs.

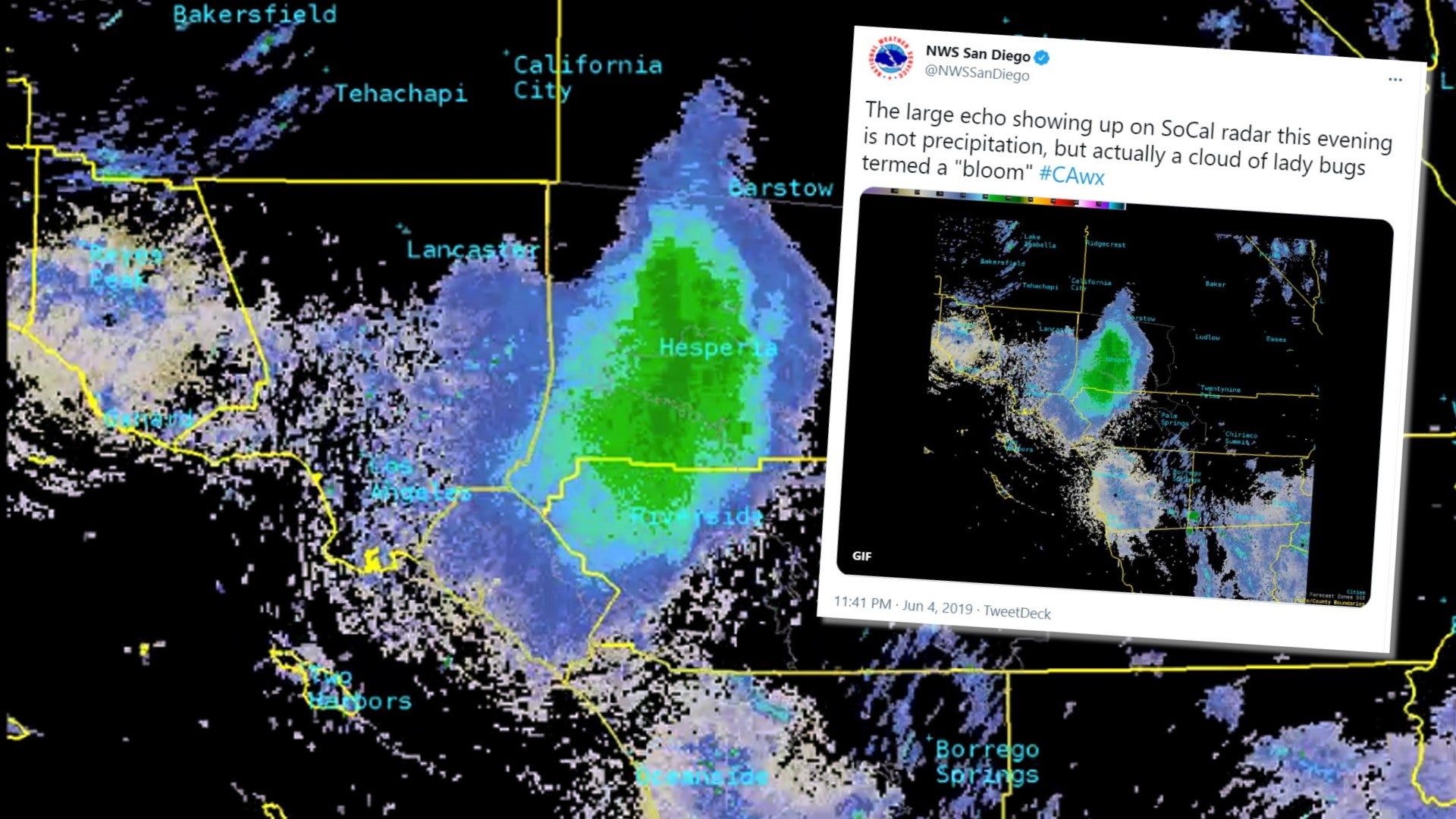

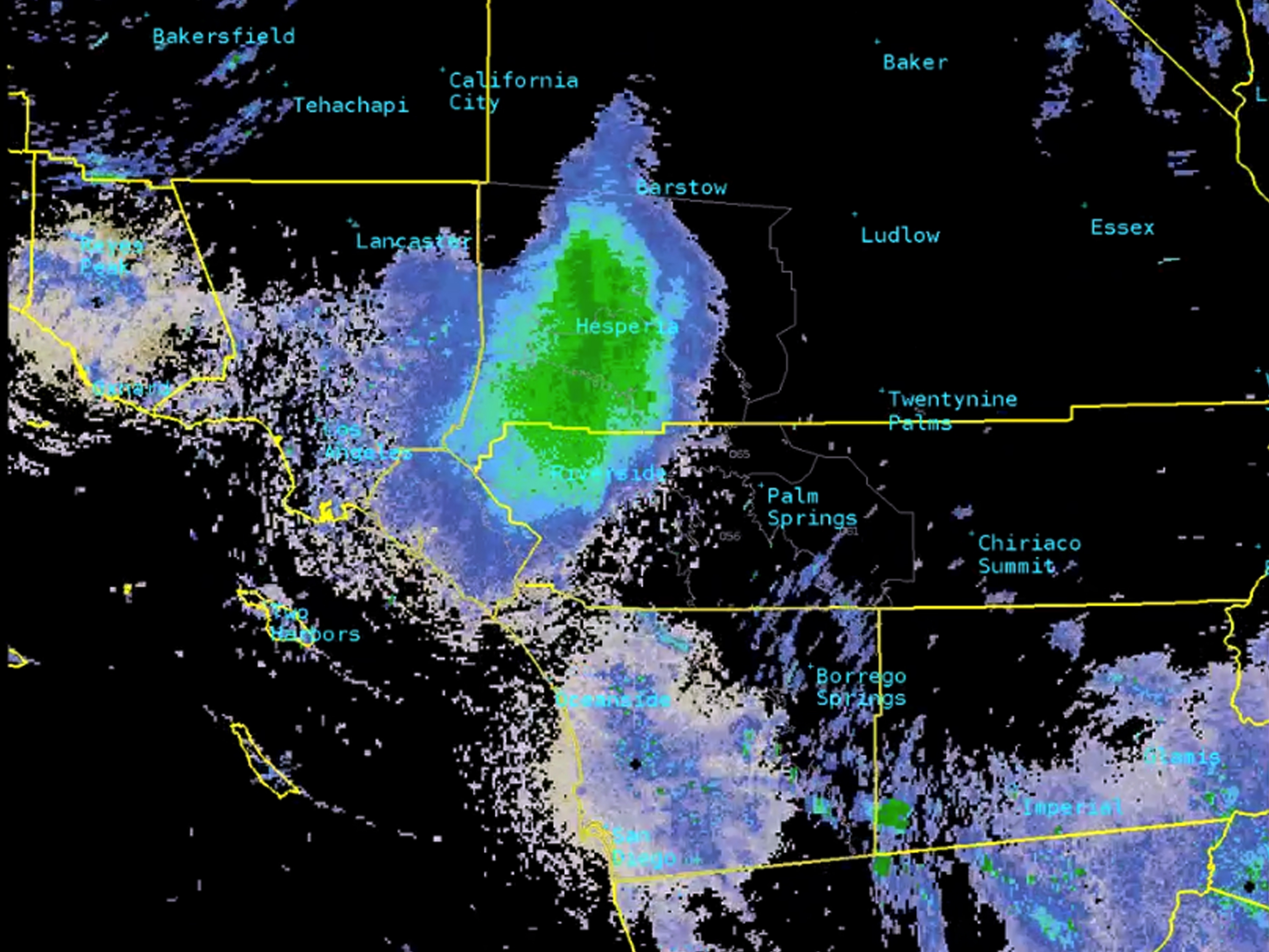

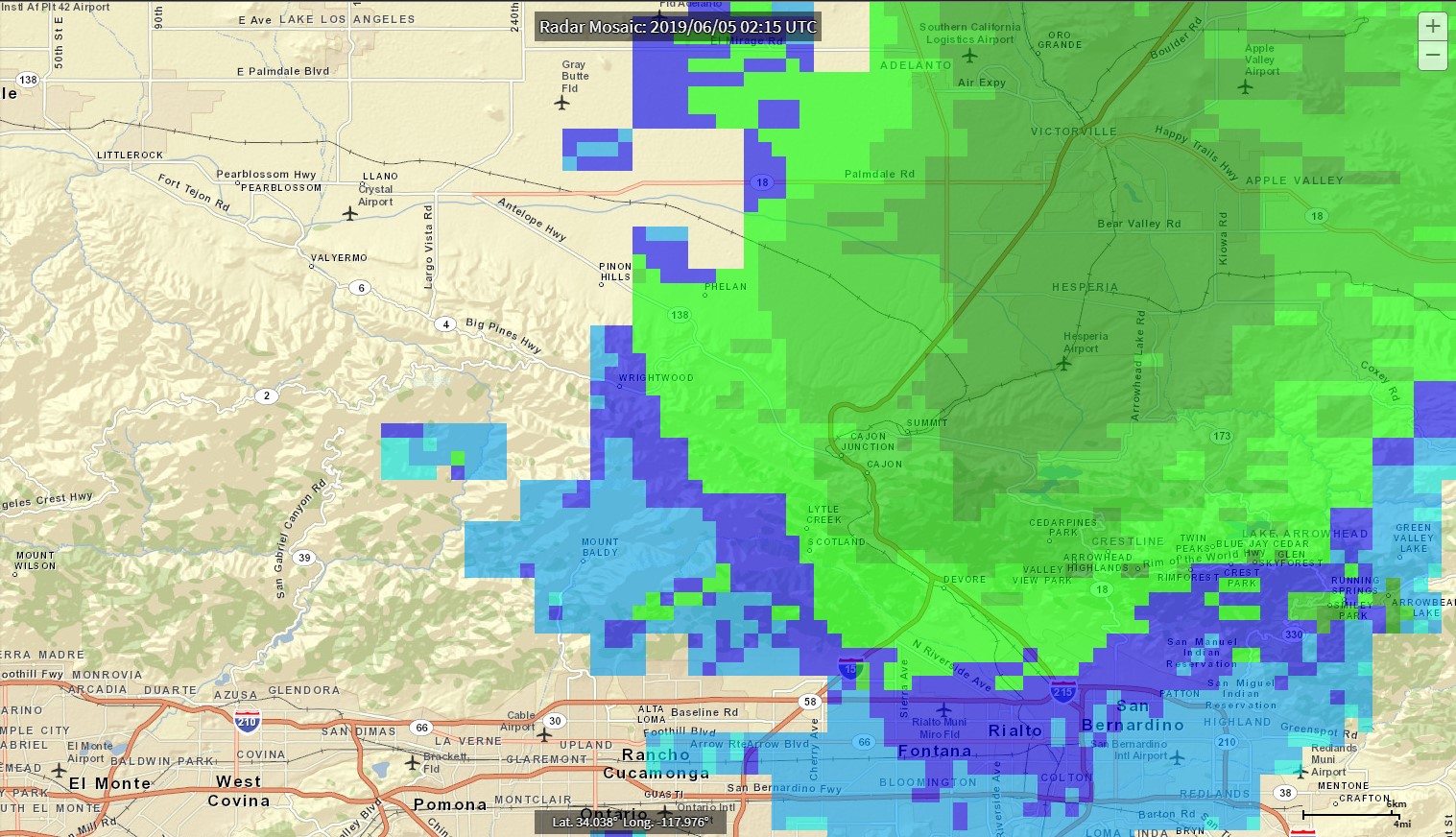

Here’s what happened: On June 4, 2019, at roughly 3:35 PM local time in California, a strange bloom began appearing on weather radar across a large swath of the southern part of the state before drifting for hours into the night. The National Weather Service (NWS) office in San Diego reported the bloom on Twitter, and posted an animated image that clearly showed a linear radar bloom heading southward from an area just north of the city of Barstow, before expanding into a more amorphous cloud shape. Also accompanying the NWS’s tweet was the caption “The large echo showing up on SoCal radar this evening is not precipitation, but actually a cloud of ladybugs termed a ‘bloom.'” Within hours, news outlets across the world began running headlines about the alleged ladybug swarm.

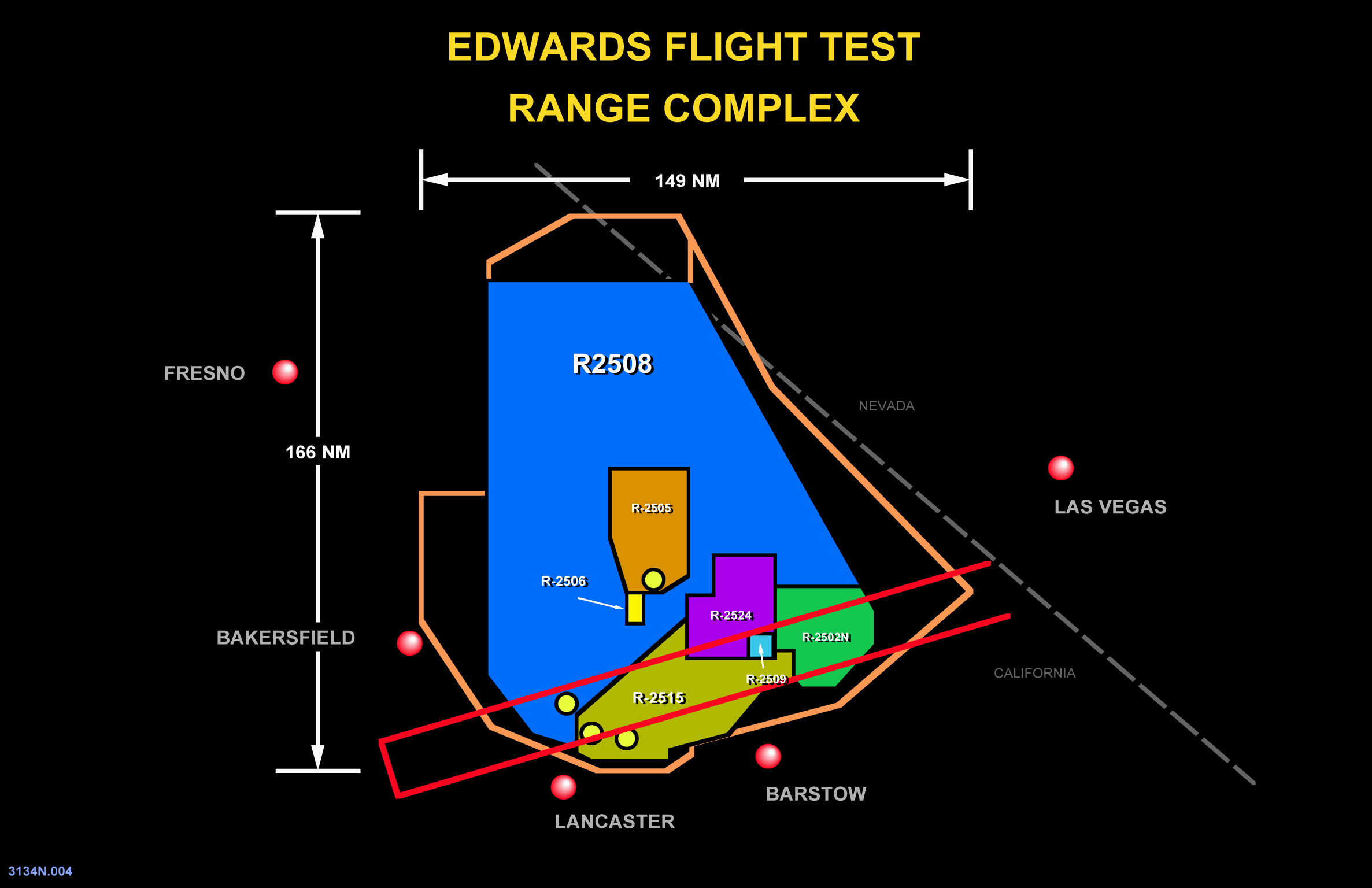

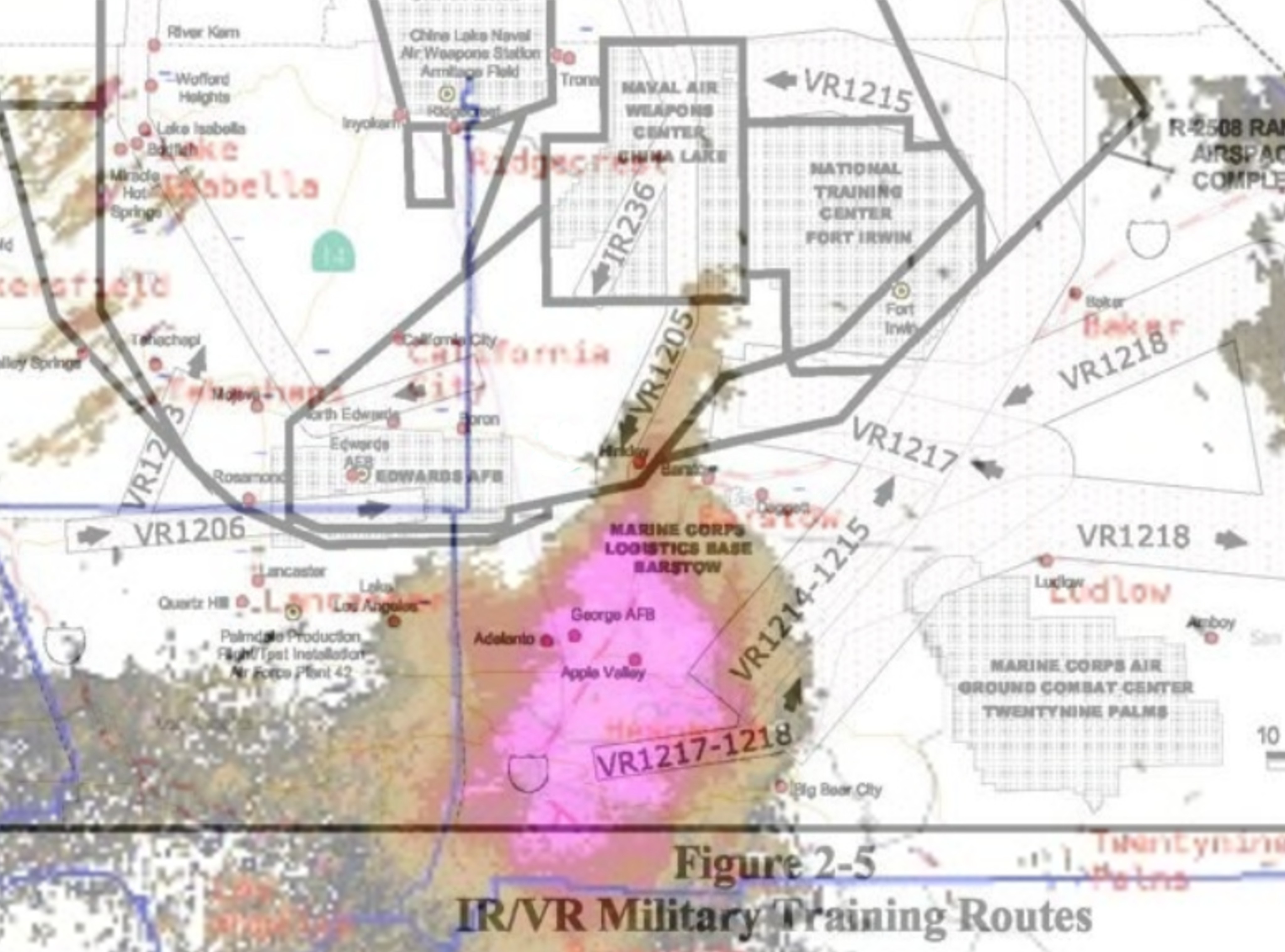

Curiously, not one outlet made mention of what lies just north of Barstow: a massive swath of military operating areas (MOA) that are often restricted for military use and that encompasses several high-profile weapons testing and training facilities. These include Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, and remote stretches of the Mojave Desert that witness tests and training sorties involving some of the most sensitive and advanced military technologies on the planet.

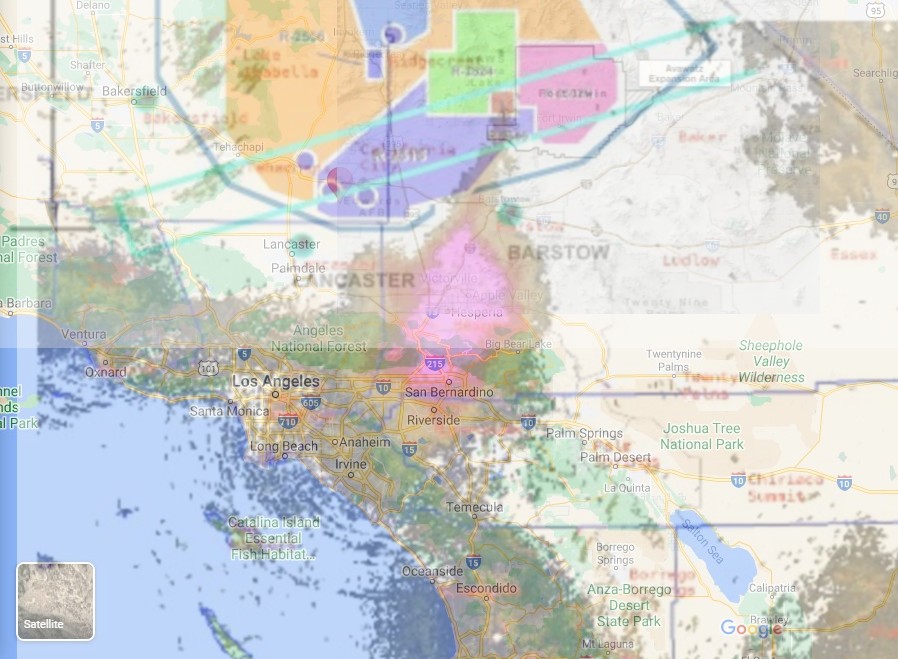

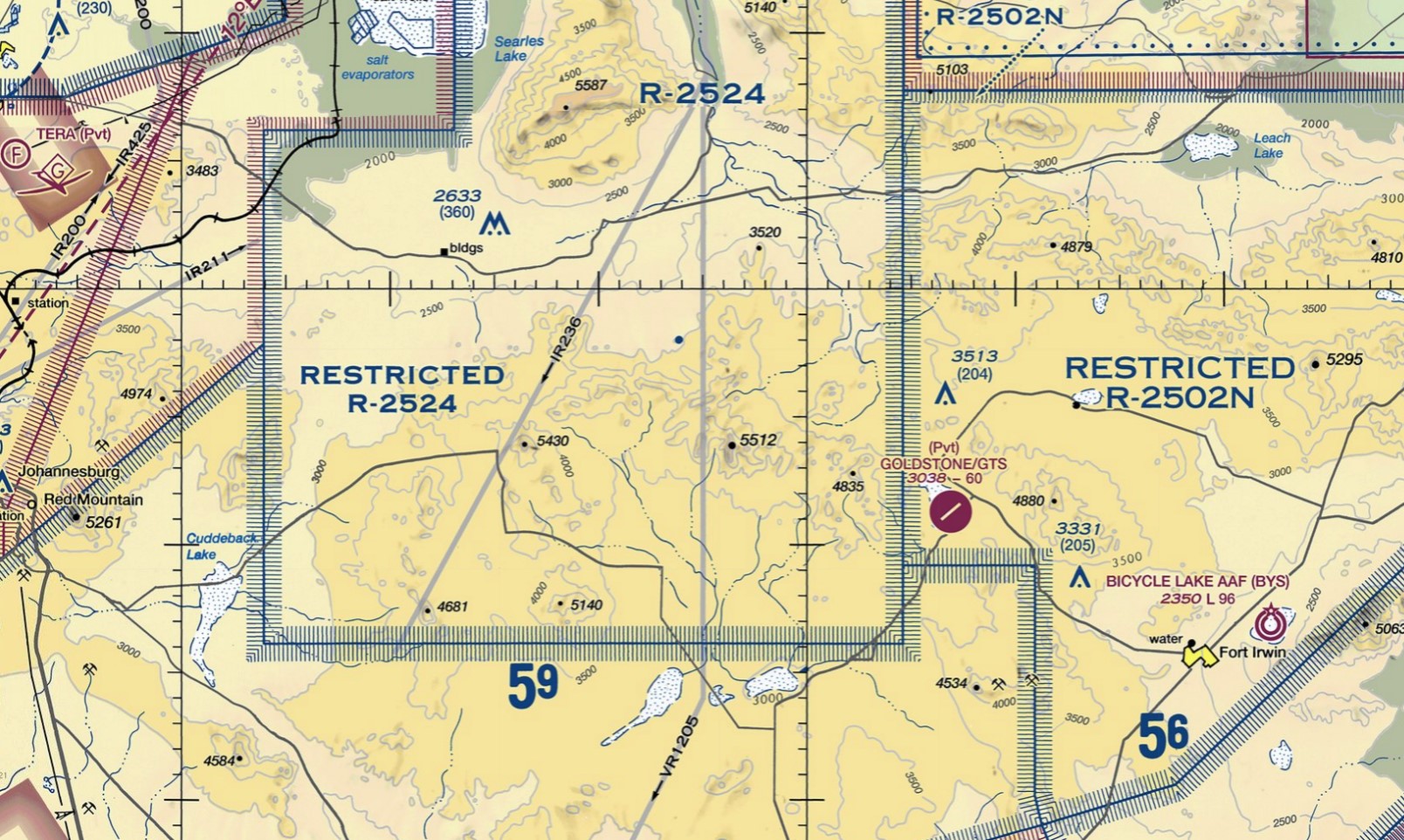

In a composite image, seen below, made by combining a Google map of the area, an airspace map published by NASA, and radar data published by NWS San Diego on Twitter, it seems that the “ladybug swarm” originated from just beyond the northeast corner of R-2515, airspace controlled by the 412th Test Wing out of Edwards, and just over the border from R-2502N, an airspace often used by the National Training Center at Fort Irwin. This location is the extreme southeastern area of the R-2524 range complex, an area that is controlled by Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake. Full descriptions of these airspaces and their uses can be found in the R-2508 Complex Users Handbook.

The area where the swarm originated appears to be a bombing range containing a mock airfield with multiple targets and a tower for scoring, located just above the two dry lake beds (coordinates 35°17’01.9″N 117°05’42.6″W) at the bottom center of the map below.

Why Did The Ladybug Story Spread So Widely?

News reports published at the time detail just how the ladybug story began. In their coverage, the L.A. Times

quoted Joe Dandrea, a meteorologist with NWS San Diego, who said he called a single weather spotter in Wrightwood, California, to ask what they were seeing at the time of the reported bloom. “I don’t think they’re dense like a cloud,” Dandrea said. “The observer there said you could see little specks flying by.”

The Washington Post quoted Mark Moede, a NWS meteorologist at the San Diego office, who likewise said the office called a single volunteer weather observer in Wrightwood, who told the office they saw “ladybugs everywhere.” Moede told The Washington Post that the reported swarm was so large that “it does raise the question of whether it could be something else.” In particular, Moede said it’s possible the bloom seen on radar was due to chaff.

Chaff is a radar countermeasure first developed for use in World War Two, which typically consists of aluminum strips or metalized glass fibers dispersed into the air to reflect radar waves. This, in turn, creates radar returns that can hinder an adversary’s ability to track aircraft, missiles, or other aerial threats. Chaff is sometimes released in military exercises and occasionally drifts into civilian areas outside of MOAs.

The Guardian quoted yet another NWS meteorologist in San Diego, Alexander Tardy, who stated “It’s definitely not birds, and it’s not bats. But we’re still not sure if it’s ladybugs.” Once again, Tardy stated it could have been chaff. “Because this was at night, the visibility would have been low,” Tardy said. “And whatever we caught on the radar was pretty high up – more than 5,000ft in the air.” The Guardian contacted both Edwards Air Force Base and the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center at Twentynine Palms, but neither responded to requests for comment.

The Guardian also cited several entomology experts who stated that it would be unusual for such a high concentration of ladybugs in California to migrate all at once. “They tend to move gradually rather than in huge clusters,” Steve Heydon, a curator of the Bohart Museum of Entomology, told The Guardian. “It’s not like they’re caribou or something.” A University of California, Davis entomologist was quoted in the same piece as saying it was rather late in the year for ladybugs to be migrating.

Meanwhile, NPR spoke with NWS San Diego meteorologist Casey Oswant who said “we were seeing something that indicated there was something out there.” Once again, Oswant cited the single weather spotter in Wrightwood, California as the source of the ladybug explanation.

By the time the “mass of ladybugs” was closest to being directly over Wrightwood, where the weather spotter was said to have been located, it was 02:15 UTC, or 7:15 PM local time. The sun set in Wrightwood, California at 7:59 PM, with twilight ending at 8:28 PM, so it’s quite possible for the spotter to have seen ladybugs in the area at the time.

Do Massive Swarms Of Ladybugs Really Bloom Out Of The Mojave?

On the online forum WrightwoodCalif.com, Wrightwood residents have been discussing ladybug blooms and infestations for years. In a thread dating back to May 28, 2003, one forum member wrote that large amounts of ladybugs appear each year in Wrightwood.

The day after the NWS reported the ladybug swarm in June 2019, one WrightwoodCalif.com member wrote “In this area, ladybugs emerge from their wintering locations in crevices in the mountains at this time. They over-winter in large groups, often a foot or more thick. When the weather warms, they emerge. No one drops them from helicopters. They show up every year. This is nothing new. Welcome to Wrightwood.”

Continuing this helicopter theme, on May 10, 2012, the administrator of the WrightwoodCalif forum, username “Wrightwood,” jokingly wrote “they haven’t started releasing ladybugs from the black helicopters yet.” Apparently, in some locations, there are conspiracy theories and urban legends about helicopters releasing clouds of ladybugs in order to reduce aphid populations and boost agriculture output. Similar unfounded claims about airdropped insects have been made in other parts of the country, and an urban legend about helicopters dropping ladybugs grew so rampant in Virginia that the entomology department at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University ran a story in 2012 in the Virginia Tech Daily to address the rumors.

It is worth noting that the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) does actually oversee a program that involves airdropping sterile Mediterranean fruit flies, or Medflies, not ladybugs, for pest control purposes. You can read more about that operation here.

Conspiracy theories, as well as the very real Medfly Preventative Release Program, aside, these forum posts would suggest that Wrightwood and the surrounding mountains are home to large ladybug populations every year. That would make sense, given that some 50 miles to the west in the San Gabriel mountains, the aptly named Ladybug Canyon has long been known as a hibernation location for ladybugs, also known in some parts of the world as “ladybirds” or “ladybird beetles.” Another nearby canyon is home to large swarms of ladybugs in late Spring.

So, there is plenty of evidence of dense ladybug populations in the San Gabriel Mountains south of the Mojave Desert. Could such a bloom come out of the desert below the mountains, though? According to the ecologists and entomologists The War Zone spoke with, such an event at that time of year would be rare, to say the least.

Dr. Peter Brown, Senior Lecturer in Zoology at Anglia Ruskin University and co-lead of the UK Ladybird Survey, found the size of the bloom as odd. “I am struggling to see how a ladybird swarm could be so massive,” Brown told The War Zone by email, “so I am skeptical about that part.”

In emails provided to The War Zone, Phillip Stepanian, a research assistant professor at the University of Notre Dame who specializes in Biometeorology and Animal migration and dispersal, stated that some members of the radar meteorology community had their doubts about the reported swarm at the time of the incident:

Based on discussions within the weather radar community, we’ve come to the consensus that the “bloom” detected by radar was most likely a release of military chaff, probably associated with training flights out of Edwards Air Force Base. Among some of the evidence leading to this conclusion were estimates of aerial densities of ladybugs, which as [others] have similarly noted would be quite extreme. It would have been nearly impossible for such high numbers to have been present in highly populated areas with no records of observations. Similarly, the bloom extended to altitudes that would have been far too cold to support ladybug flight.

James Cornett, senior scientist with James W. Cornett Ecological Consultants, told The War Zone that since ladybugs are exothermic, it is highly unlikely that they can fly at all at the kinds of altitudes reported on June 4, 2019. Furthermore, when compared with other environments, “the desert does not usually spawn masses of organisms,” Cornett said. Shortly after the ladybug swarm was reported, Cornett was quoted in the Desert Sun newspaper as saying there would have been “unbelievable numbers of telephone calls to the police” if such a massive swarm as was indicated by radar descended on Southern California.

When The War Zone reached out to Cornett, he told us that while the case is strange, pinning down a definitive answer could be difficult due to the scarcity of data surrounding such anomalous incidents:

If they were ladybug swarms (they are actually beetles, technically not bugs), why were there no visual reports? At the time, I checked with several people in the Victorville area, all biologists or naturalists, none reported seeing the swarm. Again, if it was a ladybug swarm, perhaps our detecting equipment was not sensitive enough in the past. We didn’t detect them because we did not have the sophisticated equipment that we have today?

Climate change is very real but I’m not prepared to go there first with the paucity of information that we have. Sometimes it seems that any anomaly is blamed on climate change. It’s on the tip of everyone’s tongue. I am not saying that such a swarm, if there was one, might not be somehow associated with climate change, just that we have no way of knowing.

The darn thing about any anomaly is that it’s almost always a single data point: no trends, no second chances and no trace.

The War Zone reached out to multiple local news outlets in the area, some of whom asked readers to send in pictures of the ladybug swarm in their coverage of the event. None responded for comment.

In fact, it seems there are no pictures of any anomalously large concentrations of ladybugs on social media during the week following the reported swarm. Many of the largest forums on social news aggregator Reddit that are related to the area in which the swarm was reported (r/Wrightwood; r/InlandEmpire; r/SanGabrielMountains; and r/CaliforniaPics) contain zero posts that include the term “ladybugs.” The only result on the subreddit r/California is a link to CBS News’ coverage of the ladybug swarm from June 4, 2019.

Similarly, there are no pictures of masses of ladybugs to be found on Twitter for the day of the swarm and the week proceeding it.

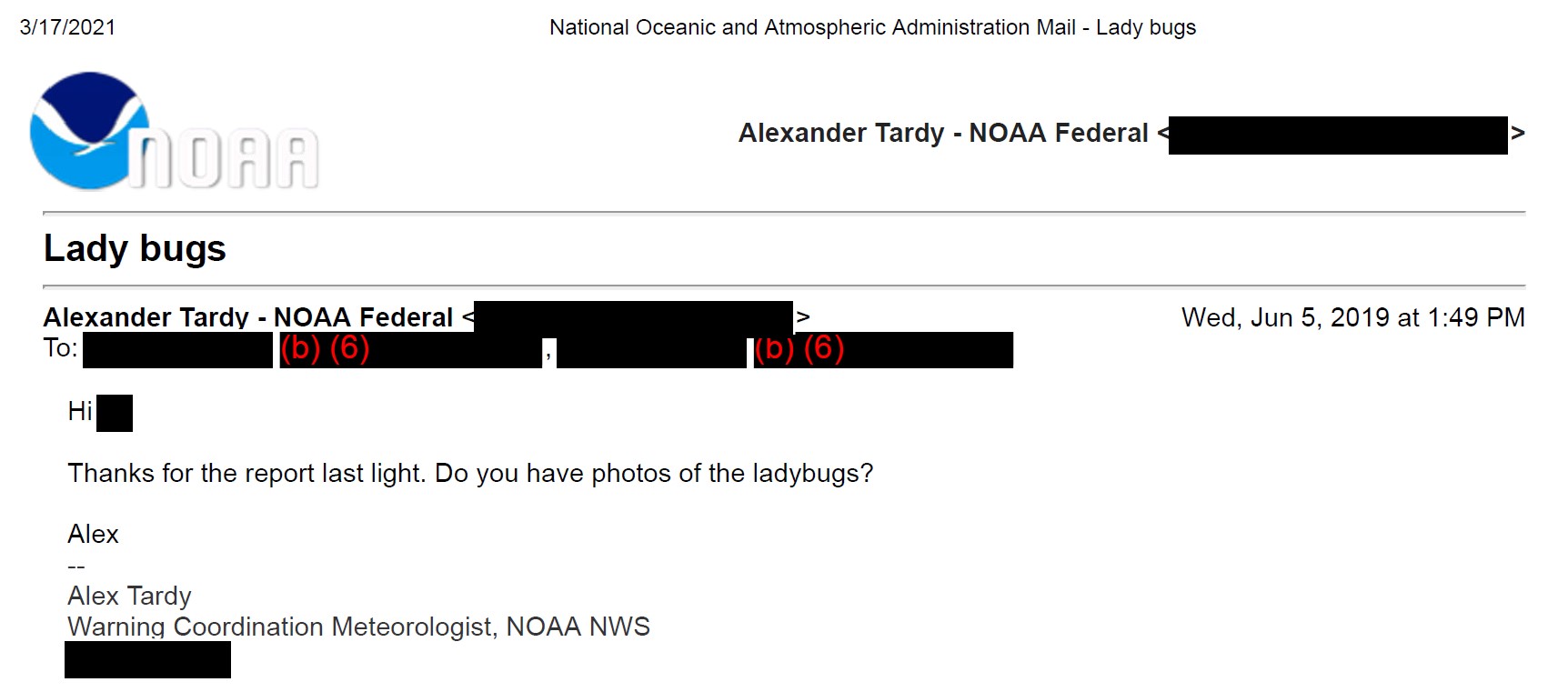

In NOAA emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), a NWS San Diego meteorologist reached out to the weather spotter who first reported the ladybugs to see if they had any pictures of the insects. It does not appear the spotter responded with any, as this is the only email in this chain in the FOIA releases.

What Does The Radar Data Show?

There is a precedent for insects to show up on weather radar, and NWS meteorologists have been quoted before as saying insect swarms detected by radar may not be dense enough to be visible from the ground.

A spokesperson for the NEXRAD Radar Operations Center at NOAA told The War Zone via email that while it is common for NEXRAD to detect non-meteorological features such as insects, birds, bats, or even wind turbines, NOAA does not track specific dates or times of insect blooms, and NOAA is rarely sure what type of insects or birds are detected by their NEXRAD systems. “On occasion,” NOAA’s email reads, “National Weather Service offices will post on social media about these detections.”

One way of telling what the radar bloom may have been is to examine what is known as dual polarization data. By 2013, National Weather Service Next-Generation Radar (NEXRAD) systems had been upgraded to be able to more accurately determine the shape, orientation, and distribution of various scattered elements that make up a radar return. The resulting measurement, known as a correlation coefficient, can provide a picture of how similar the different particles within a radar return are. If that data was available, one would be able to more accurately determine if a given return was chaff, precipitation, or a swarm of insects or other organisms.

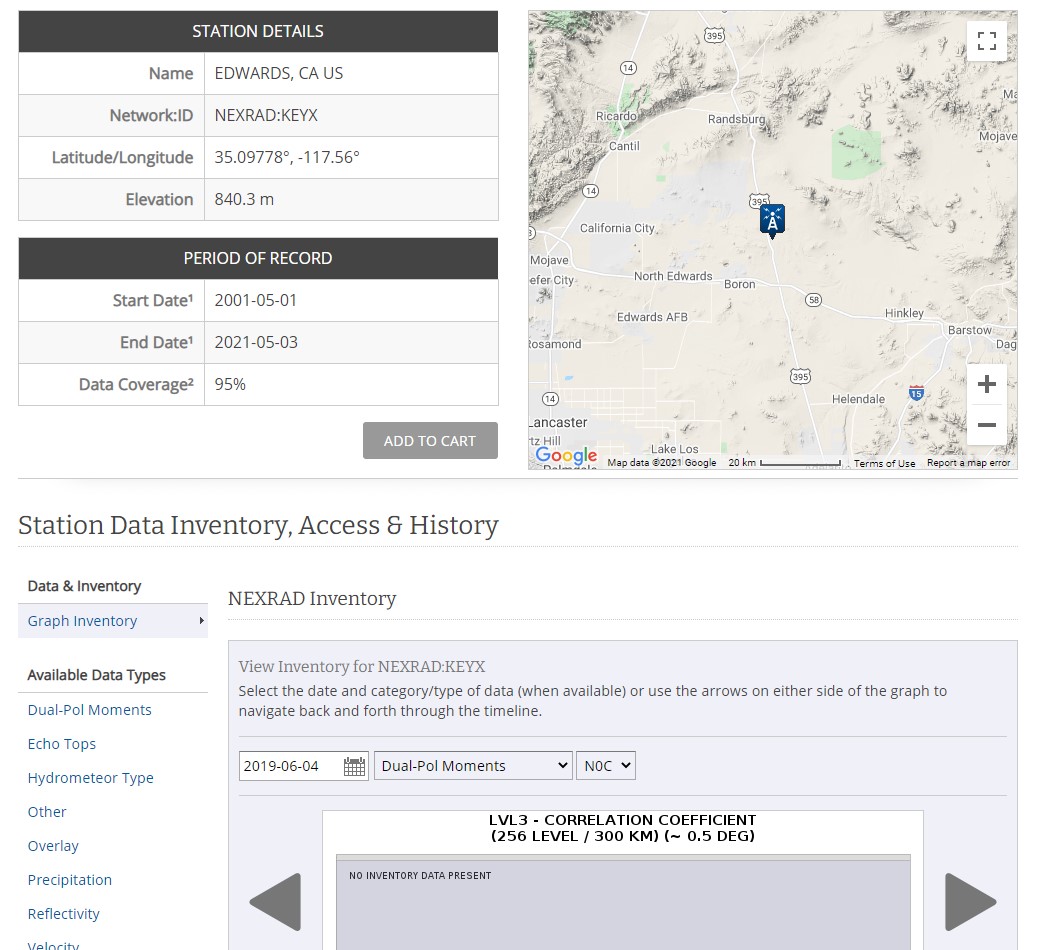

NOAA’s NEXRAD III archives have a 95% data coverage of the NEXRAD station at Edwards, California. That means for 95% of dates between May 1, 2001, and May 3, 2021, the archive contains comprehensive radar data, including correlation coefficient, for the area in which the ladybug swarm was reported. However, there is no correlation coefficient data available at this particular station’s archive between May 28, 2019 and the evening of June 6, 2019, meaning the alleged ladybug bloom fell into the 5% of total dates over the last twenty years for which there is no data. A NOAA spokesperson told The War Zone “there was likely an outage of certain components, causing loss of the dual pol data” at the time.

Emails Reveal Even NOAA Didn’t Buy The Ladybug Story

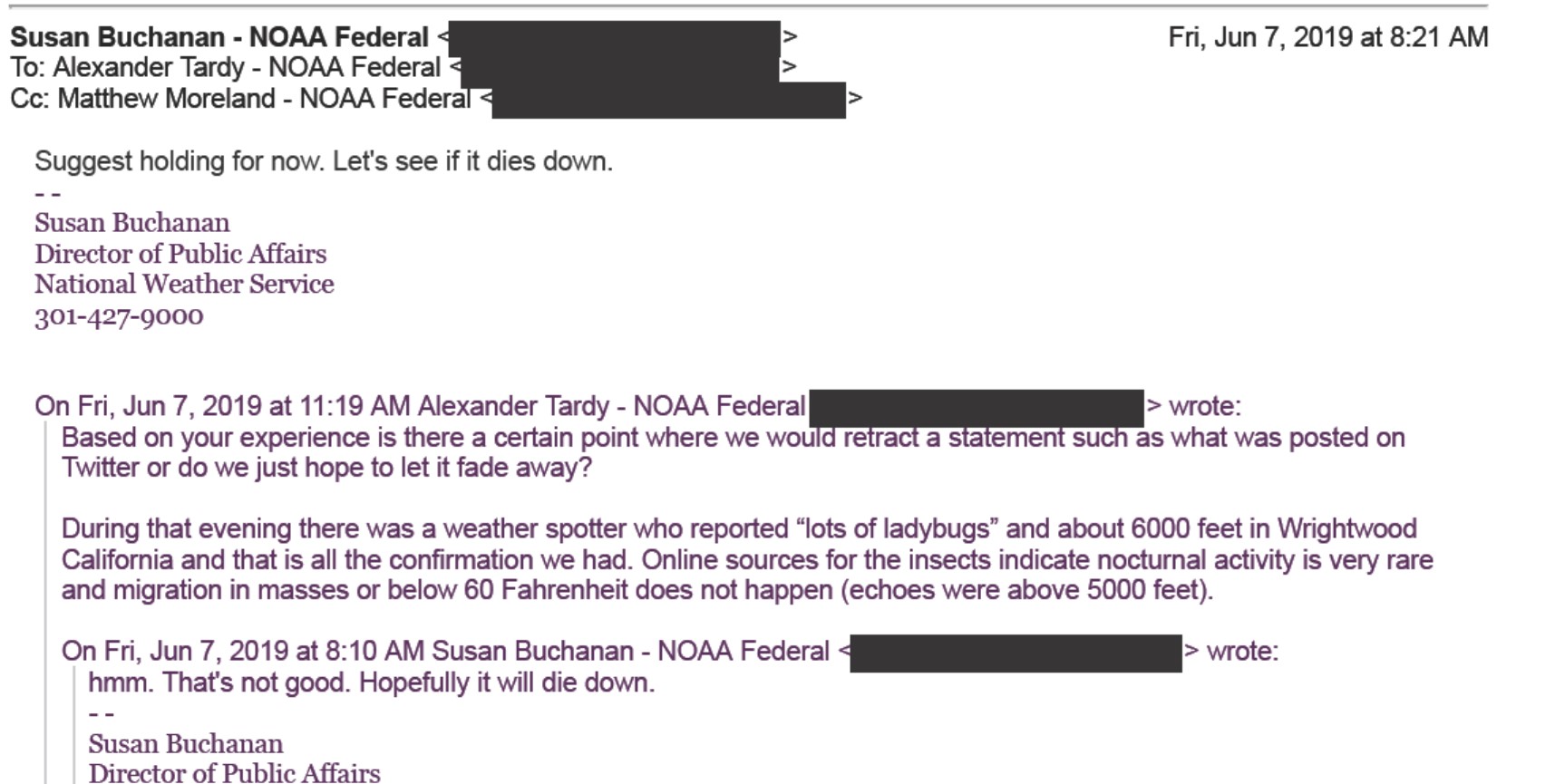

Despite the scarcity of detailed radar data, internal NOAA communications obtained through FOIA show that several NWS San Diego meteorologists and staff members doubted the ladybug story themselves even as they confirmed the story to the media, all while inquiring amongst themselves if their initial tweet about the swarm should be retracted.

Susan Buchanan, who was at the time Director of Public Affairs for NWS, stated three days after the bloom was reported that it’s “not good” that the specifics of the incident do not match traditional ladybug behaviors. “Hopefully it will die down,” Buchanan wrote. The same email confirms that the entire ladybug story was based on a single weather spotter’s observations.

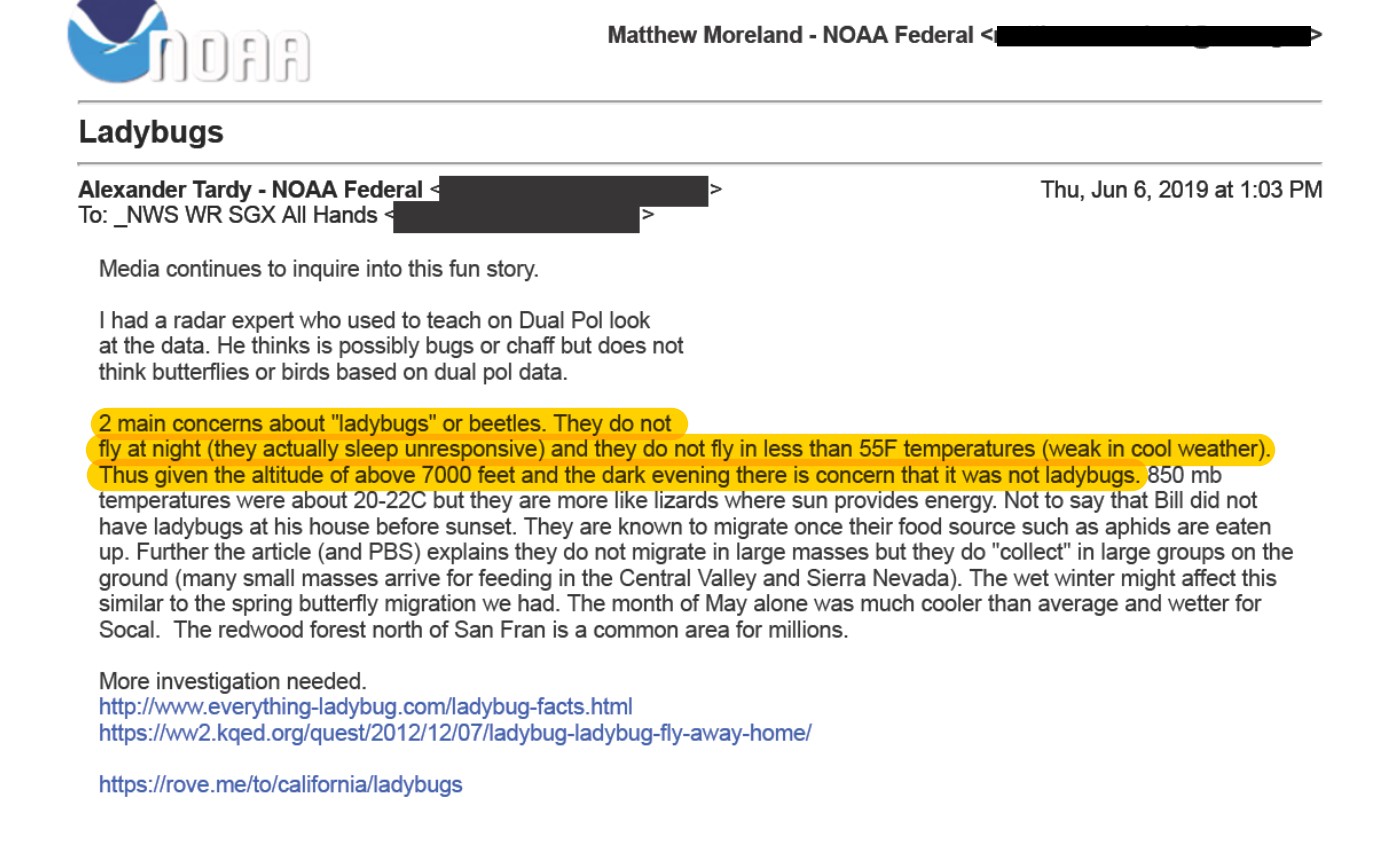

NWS San Diego meteorologist Alexander Tardy confirms the suspicions of the entomologists cited above, noting that the altitude, time of day, and temperature seem anomalous, adding “there is some concern that it was not ladybugs” and that “more investigation [is] needed:”

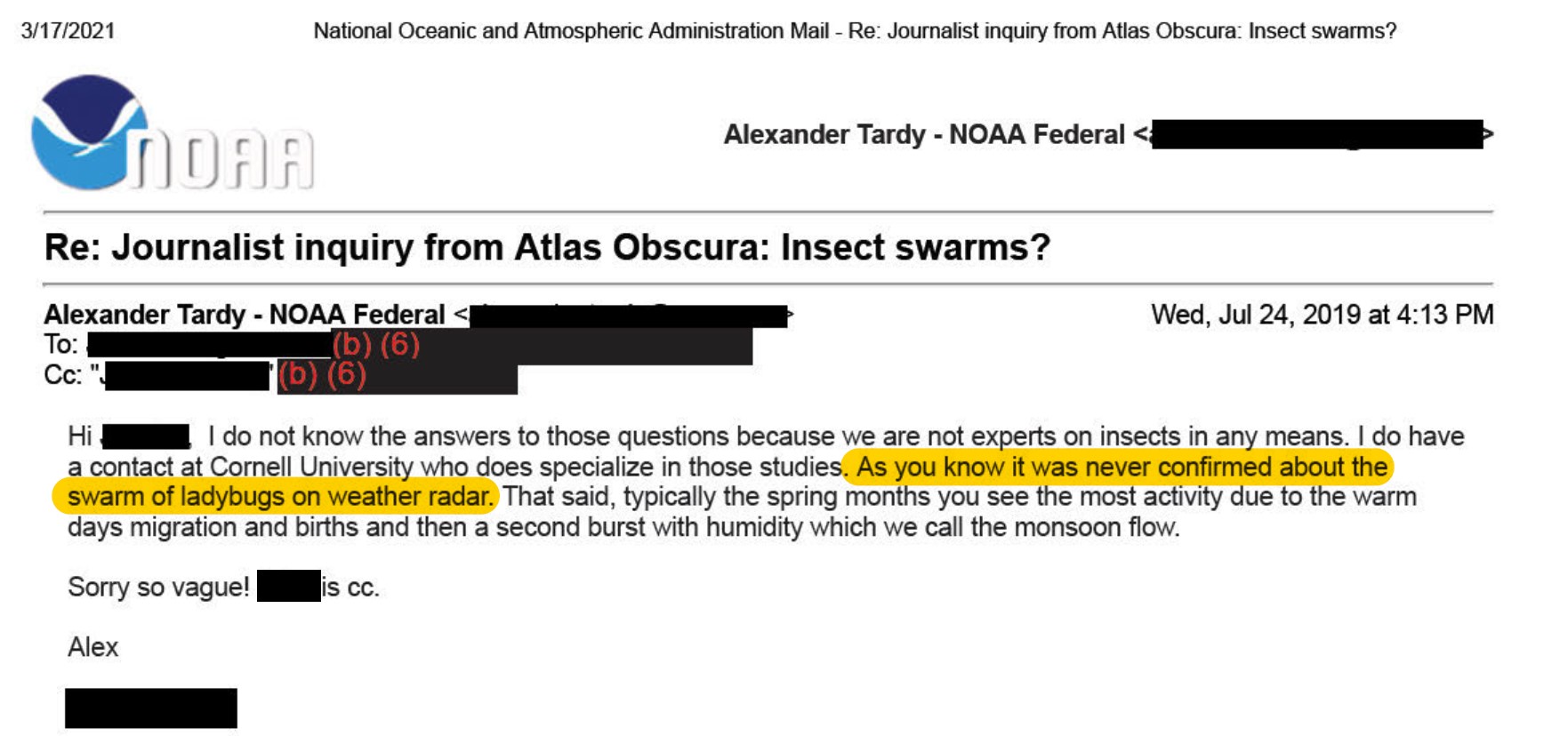

Tardy builds on these concerns in another email, dated July 24, 2019, when he responds to a journalist’s inquiry with “As you know it was never confirmed about the swarm of ladybugs on weather radar.”

In a June 11, 2019 email sent to a Cornell University entomologist, Tardy wrote that “Military chaff can look like this but typically not this wide unless something is spreading it out and trapping it like the inversion.” Another email between the two states that there was indeed a strong temperature inversion and an “unstable layer at that altitude” on the night of the alleged ladybug bloom, which would “support suspending any type of small particle” in a drifting pattern from north to south.

A June 6, 2019, email between a NOAA affiliate and Tardy strikes a joking tone, noting in reference to the doubts about the ladybug story “But NPR did a story about it, therefore it MUST be true!!” followed by a smiley face emoji.

Tardy wrote another NOAA employee on June 6, 2019 adding that chaff releases take many “sizes and shapes” on radar in the area and that he believed he had seen chaff released from ground-level sources in the past.

Building on this, Tardy wrote to NWS Director of Public Affairs Buchannan three days after the incident, writing that “the bottom line is we do not know if this is insects and it’s not consistent with ladybug behavior.” Tardy then adds that chaff in the area frequently takes on various forms on radar.

We reached out to NWS San Diego and Tardy, specifically, on multiple occasions to inquire about the ladybug swarm, but did not receive any replies.

FOIA requests made to the 412th Test Wing Public Affairs Office and all other Public Affairs Offices at Edwards Air Force Base turned up no records for any communications containing the term “ladybugs.” Similarly, the Table Mountain Facility, operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory near Wrightwood, returned zero records containing the term “ladybugs” or “ladybug swarm.” The War Zone is still pursuing FOIA requests related to the incident with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the U.S. Army’s Fort Irwin, and the U.S. Navy’s Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake.

If It Wasn’t Ladybugs, What Was It?

The SoCal “ladybug swarm” of June 4, 2019, is similar in many ways to a separate incident that occurred at the Army’s Redstone Arsenal, also referred to as RSA, near Huntsville, Alabama. On June 4, 2013, a strange radar bloom appeared on weather radar operated by the NWS in Huntsville. The bloom did not disperse into the wind, but instead lingered in the air for over nine hours. Due to widespread media coverage of the event, Redstone issued a press statement on June 6, 2013, stating that they were, in fact, responsible for the strange radar bloom, which was caused by a release of chaff:

During these tests RR-188 (chaff) was dropped from aircraft. This chaff showed as an anomaly on local weather screens as weather conditions caused it to linger longer than normal. This substance is commonly used by the military in training and testing operations. There are no known environmental effects caused by RR-188.

According to a study of the Redstone incident published in the Journal of Operational Meteorology, the media fervor over the ordeal was made worse by “RSA’s initial reluctance to confirm the chaff release as the source of the radar echo and the fact that radar-observed chaff echoes are uncommon near RSA.” The study’s authors write that “the unusual nature of the event presented unique operational challenges for the NWS Weather Forecast Office (WFO) in Huntsville,” as meteorologists had to “balance scientific expertise and transparency with potential military operations impacts.”

There were several similar chaff incidents throughout 2018 and 2019. In late 2018, The War Zone reported that a mysterious plume lit up weather radar screens across Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky, and was confirmed the next day to have been chaff ejected from a West Virginia Air National Guard C-130H Hercules cargo plane. The same day the C-130H was confirmed to have been the cause of that plume, two more anomalous radar blooms were detected over Maine and Florida. No cause has yet been identified for those, but they happened close to, or inside of, Military Operations Areas. Once more, in March 2019, a chaff cloud was observed in New Mexico near Cannon Air Force Base. The base did not respond to The War Zone when asked about the cloud.

These are just a few outstanding examples of military chaff releases caught on weather radar in recent years, and there have been plenty of others that have not received widespread media attention.

While the Redstone Arsenal and West Virginia Air National Guard incidents were confirmed as chaff, the others were not – nor was the “ladybug swarm.” Yet based on the fact that tests and training exercises are conducted in the area of the bloom’s origin, it’s very likely that chaff was responsible for the event.

For instance, in the United States Air Force F-35A Operational Beddown Air National Guard Environmental Impact Statement published in August 2019, the authors stated that “the ARM-210 chaff proposed for use by the F-35A is currently unavailable and undergoing operational testing” but that “it is expected to be ready for use in 2020.” If operational testing of chaff systems was occurring in August 2019, and presumably prior to that while that impact statement was being drafted, then it’s possible that at least some of the 2018 and 2019 radar blooms and/or chaff incidents could have been among those operational tests.

Of course, this is only one possible explanation, as there are many other testing and training events that could have been the culprit, given that the area in which the swarm was reported to have originated is a major nexus for the U.S. military’s training and testing. Aircraft use those ranges daily for all sorts of needs. And given that a bombing range was directly underneath where the swarm appeared to have originated, the origins of the chaff cloud seem fairly clear. Even a release by accident is possible.

It is also worth noting that the ladybug swarm was reported in the midst of Green Flag-West 19-8, a live-fire air-land integration combat training exercise which took place at Fort Irwin, but included aircraft from around the region.

Letting The Ladybugs Out Of The Bag

The circumstances surrounding the SoCal “ladybug swarm” incident and subsequent media feeding frenzy are important for a number of reasons. For one, it shows how even relatively benign military aircraft activities – releases of chaff – can be denied or ignored by the Department of Defense. After all, why reveal elements of your aircraft testing or even minorly disruptive exercises when you really don’t have to?

Secondly, the ladybug swarm case demonstrates how a click-worthy, attention-grabbing headline can circulate wildly throughout a media that is very hungry for readers’ eyeballs. Note just how many outlets cast doubts on the ladybug story, or even mentioned chaff as a potential counter-explanation, yet still ran the “massive ladybug swarm” headline anyway. Even the NWS had its doubts about the story, and considered retracting its initial tweet, but let the ladybug story proliferate wildly nevertheless.

Now consider how many tests or exercises are conducted that involve aircraft or weapons systems that are much more sensitive than chaff countermeasures. Obviously, the DOD would need a much bigger headline than simply a large swarm of bugs to cover for such tests when or if they occur within sight of prying eyes. It’s possible that similar major headlines about other anomalies that could have been related to military testing went by uncorrected.

When it isn’t absolutely critical information, it seems that the media is game to go along with the sensationalism even if they are aware more mundane explanations exist. Of course, in this case it is merely some phantom ladybugs at stake, but next time it may be a matter of greater importance, and regardless, accuracy should still matter.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com