One of America’s most closely guarded secrets is the procedure to ensure the survival of the president and his or her senior defense advisors in the event of a national emergency. Until the advent of nuclear weapons, this was easily accomplished by means of secure basement-level rooms at the White House and the Pentagon. Soviet acquisition of “the bomb” changed this calculus, necessitating the relocation of the president and his advisors to long-term facilities outside of Washington DC, such as the Alternate National Military Command Center at Raven Rock, Maryland. As nuclear weapons became more powerful, the increasing vulnerability of even these bunkers reduced their value to America’s post-crisis Continuity of Government (CoG) program.

Two options enhanced this survivability equation: airborne and shipborne command posts. In July 1960 Strategic Air Command (SAC) evaluated the use of five Boeing KC-135As as backups to the SAC underground command post at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. This test proved successful, and on February 1, 1961, SAC began 24/7 Looking Glass airborne alert, so named because it mirrored the capabilities of SAC’s primary command post. At the same time, the Air Force recommended a similarly configured KC-135 be stationed at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland as a National Emergency Airborne Command Post (NEACP) for the president and his advisors. The Navy suggested using the modified cruiser USS Northampton located in the Chesapeake Bay as a National Emergency Command Post Afloat (NECPA).

NIGHT WATCH

NEACP operations began on February 19, 1962 with three KC-135A airborne command post aircraft assigned to the Night Watch program. One KC-135A, manned by a Joint Alternate Command Element battle staff (known by their static “back-end” call sign Silver Dollar), was on 24/7 alert and could be launched within 15 minutes. A second KC-135A was on a one-hour alert. The third jet was used for training when it wasn’t undergoing maintenance.

Acquisition of KC-135Bs equipped with turbofan engines, receiver air refueling capability, and enhanced communication gear resulted in the March 1966 delivery of three replacement NEACP EC-135Js. The USS Northampton assumed NECPA duties in March 1962, augmented the following year with the USS Wright. By 1964, one ship was on alert at all times. The battle staff included 17 officers and 22 enlisted personnel. You can read all about these obscure but fascinating ships in this past War Zone feature.

Surprisingly, there is no record of any NEACP inspection visits—let alone flights—by either President John F. Kennedy or Lyndon B. Johnson. Indeed, the very first presidential NEACP flight took place on May 11, 1969, when Richard M. Nixon flew from Homestead Air Force Base in Florida back to Andrews on an EC-135J. Among those accompanying Nixon on the two-hour and eight-minute, 900 nautical mile flight were his assistant for national security affairs Henry Kissinger, advisors H. R. “Bob” Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, press secretary Ron Ziegler, military aide Air Force Colonel James Hughes, U.S. Army Major General Charles Myer (a signals and communications expert), Air Force One pilot Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Albertazzie, Nixon’s physician Dr. Walter Tkach, and Secret Service agents Ronald Pontius and Arthur Godfrey.

Considering the absence of windows, the presence of a 15-member battle staff, and the paucity of “executive seats,” the flight must have been uncomfortable and claustrophobic, to say the least. Haldeman recorded the experience in his journal:

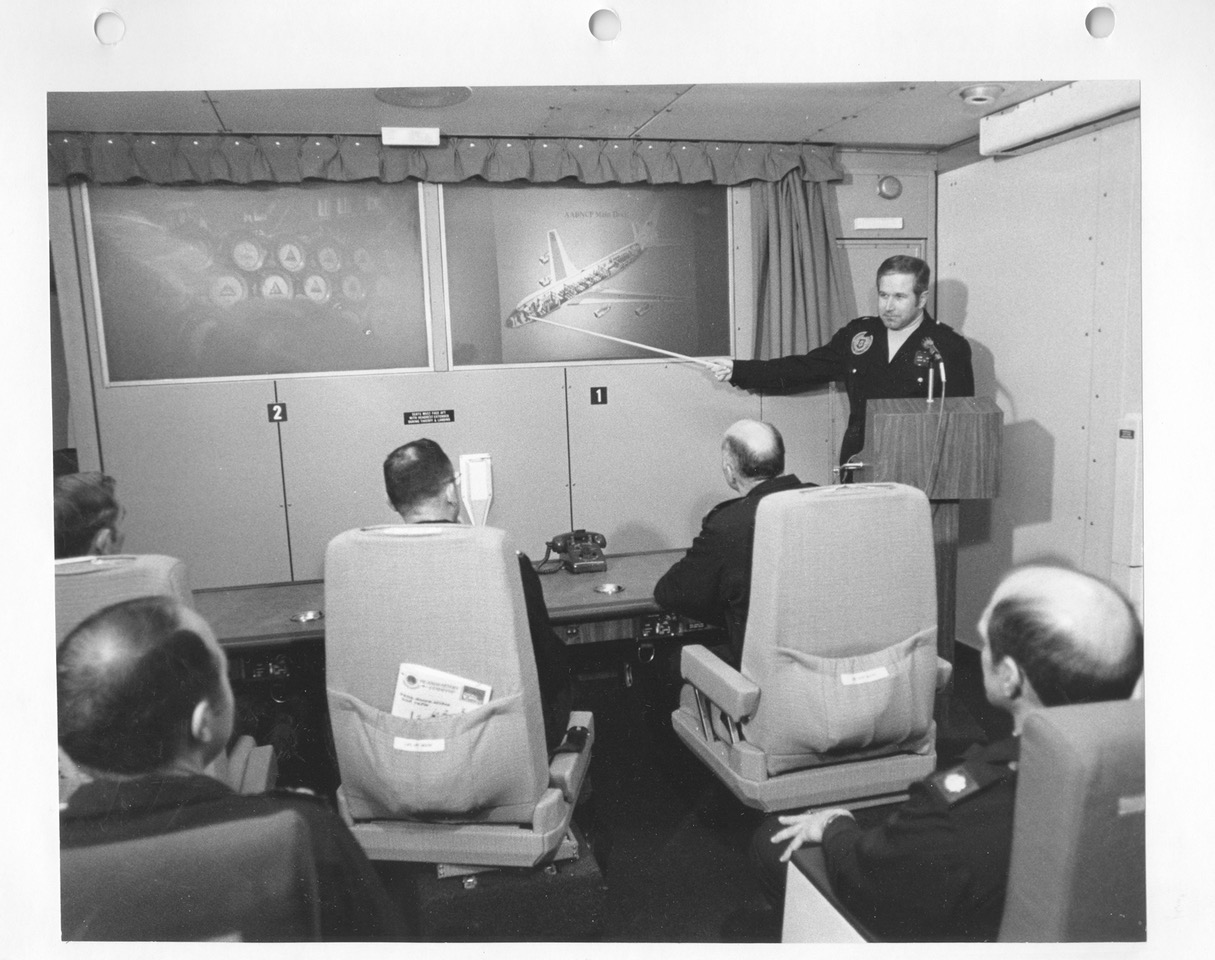

Came back to DC on the Airborne Command Post—and they staged a briefing and a test exercise. Pretty scary. They went through the whole intelligence + operational briefings—with interruptions, etc. to make it realistic. Exercise proved to P. that when the Russians appear to be launching an attack our options are pretty limited + our retaliatory strike power is pretty weak.

Fascinating plane—with command room set up—all kinds of communications, display boards, rear projection, etc. Took P. a while to get into the thing (his mind was on the peace plan) but he finally did—and was quite interested. Asked a lot of questions re: our nuclear capability—and kill results. Obviously worried about the lightly tossed-about millions of deaths.

Nonetheless, press reaction was negative to the very notion of the president surviving a nuclear strike while the nation floundered in devastation. In an April 1974 Washington Monthly article “Nixon’s Flying Füherbunker,” Mary Meehan quoted Arkansas Senator William Fulbright’s 1972 lament that if Americans heard “that danger was threatening the country [and] the President and all his staff…boarded a plane and [had] taken off and left the United States to whatever fate it may suffer … I am sure that in England, during World War II, when Churchill was standing there, trying to encourage his people to resist, it would have been a strange sight if he had taken off in a plane instead.” Meehan continued, saying that after a nuclear exchange killed 80% of the American population, “…your Commander-in-Chief will be flying around above the wreckage, getting even with the Russians and making plans for the next generation of peace.” It is hard to disentangle the media hatred of Nixon from the issue of presidential survival, but other critics wondered if there was a need for the Secretary of the Treasury to survive in order to collect income taxes in a post-apocalyptic hell and the Post Master General to register the millions of dead.

Bigger is Better

The EC-135J NEACPs were arguably only second-generation systems, vulnerable to electromagnetic pulse (EMP), as well as having inadequate crew space, limited computational and data storage facilities, and outdated communication suite technology. Planning for a replacement Advanced Airborne Command Post (AABNCP) began in the early 1960s.

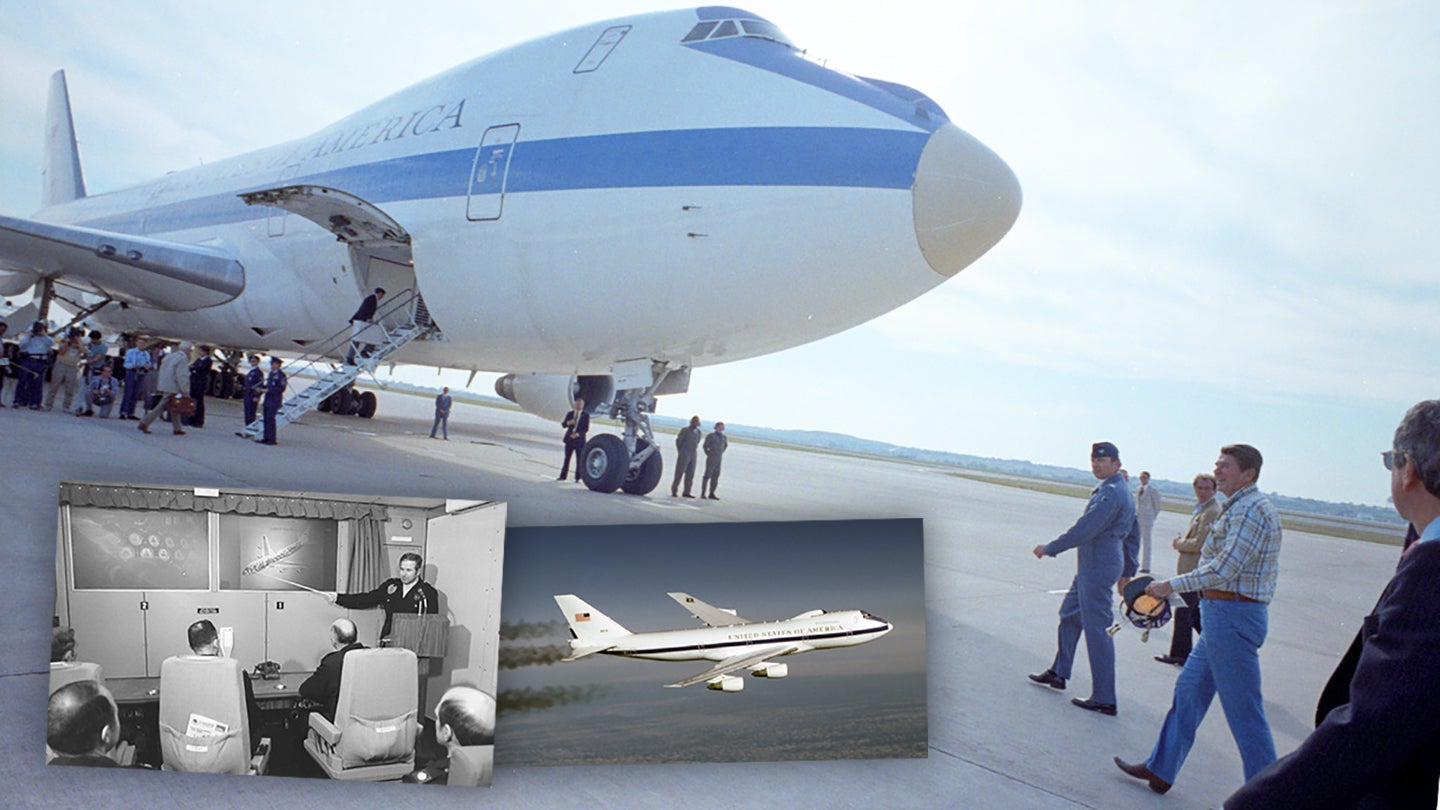

SAC originally wanted a fleet of Lockheed ‘EC-5s’, but the airplane’s troubled production and political considerations resulted instead in the selection of Boeing’s 747. In addition, SAC intended that the E-4A (later modified to E-4B standards) would replace both the entire Looking Glass EC-135C and Night Watch NEACP EC-135J fleet based at Andrews on a one-to-one basis.

In 1971, then-Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird directed the procurement of seven E-4s, with the planned first delivery in 1975. Three of these would be delivered as part of Phase I, Block I as E-4As, with the fourth delivery as an E-4B under Phase I, Block II. Options for the remaining three jets would be exercised contingent upon satisfactory completion of initial operational testing and evaluation (OT&E).

On July 28, 1975, then-Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger, under President Gerald Ford, eliminated the seventh planned jet, and, due to excessive cost overruns, deferred any decision on the remaining two unbuilt jets until FY79. One month later, Schlesinger articulated specific duty assignments for the four extant E-4s:

- One airborne 24/7 for SAC’s Commander-in-Chief (CINCSAC)

- One on ground “hot alert” (crisis or increased defense condition—DEFCON) for NEACP

- One “common” backup

- One flight crew and battle staff trainer

Obviously, these plans were unrealistic, especially the 24/7 CINCSAC mission (it was not clear if this was a replacement for the Looking Glass or if this was CINCSAC’s dedicated alert jet). Moreover, the “common” requirements meant that all E-4s would have to be configured for both the SAC and NEACP missions.

Cancellation

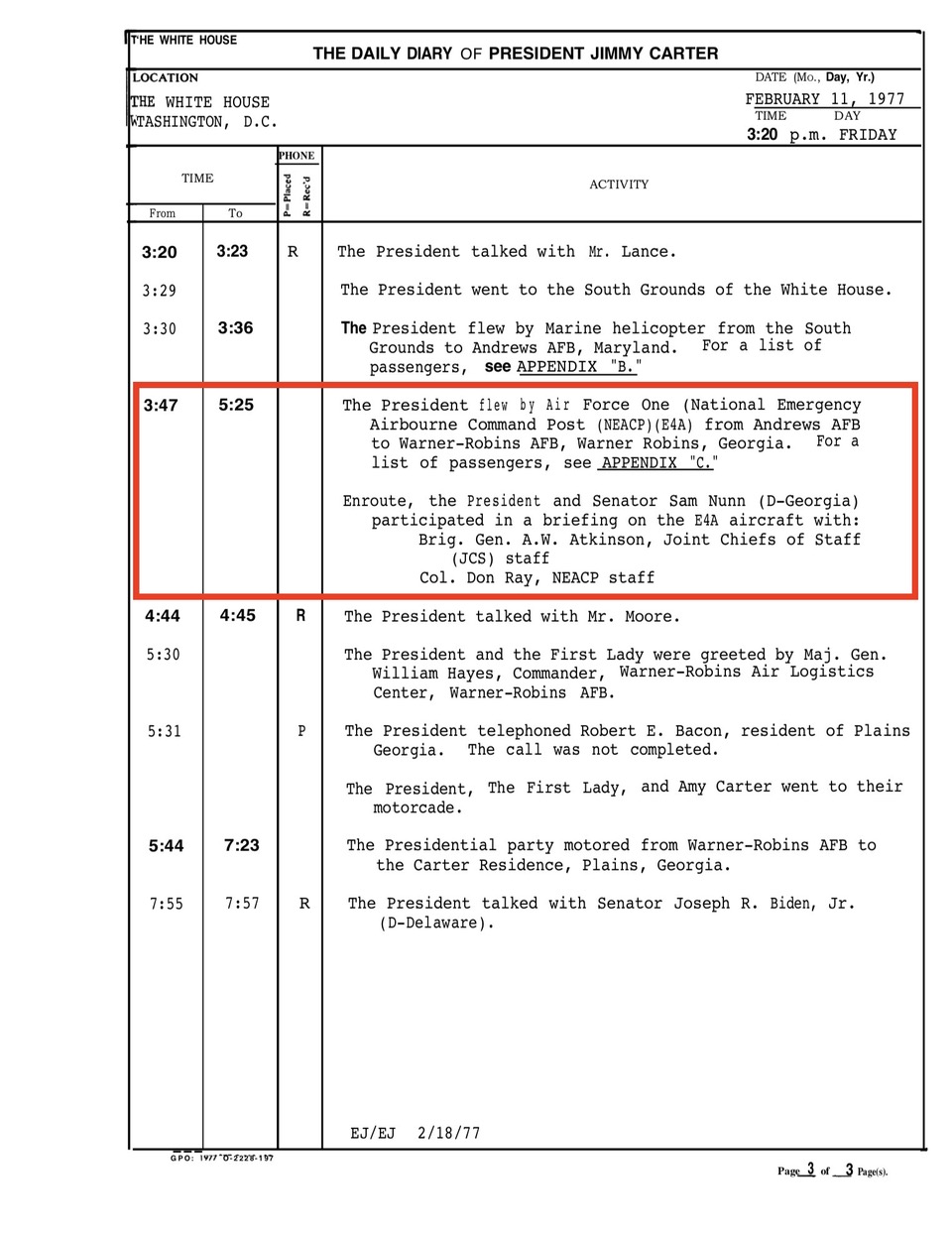

Jimmy Carter was the first president to fly aboard an E-4 NEACP on February 11, 1977, some three weeks after his inauguration. During the 1-hour, 33-minute flight covering some 500 nautical miles from Andrews to Warner Robins Air Force Base in Georgia, Carter and Georgia Senator Sam Nunn were briefed on the NEACP mission and capabilities by U.S. Air Force Brigadier General Anderson W. Atkinson, the Joint Chiefs of Staff Deputy Director for National Military Command System (NMCS). Three days later, Carter directed then-Secretary of Defense Harold Brown to cancel all remaining E-4 orders claiming they were expensive and unnecessary. Carter had made clear that, in the event of a nuclear attack on the United States, he would remain in Washington DC, and allow Vice President Walter Mondale to assume the presidential mantle after becoming airborne in the NEACP at DEFCON 2. However, gallant and patriotic this might seem, Soviet SS-N-6 Serbs fired from Yankee class boomers would reach the White House in six to 10 minutes, making this a meaningless gesture.

Of the seven original E-4s, one was canceled under Ford, two under Carter, and four remain operational today. And no, the E-4 doesn’t sit alert with one (or all four) engines running. At normal alert locations such as Offutt or Grissom Air Force Base (now Grissom Air Reserve Base) in Indiana, facilities are in place that obviate the need for power-on alert. At remote locations, leaving one engine running is an option.

Ronald Reagan was the second president to fly aboard an E-4 on November 15, 1981, from Kelly Air Force Base in Texas to Andrews. As with Carter, he received a briefing by Lieutenant General Philip C. Gast on the communications systems linking the NEACP with the National Military Command Center at the Pentagon and the ANMCC at Raven Rock. He spent the balance of the flight working alone in a forward cabin. Interestingly, the entry for November 15 is missing from the presidential Daily Diary file at the Reagan Library, so the full details of the flight and its manifest are not known.

In February 1982, then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Frank C. Carlucci invited Vice President George H. W. Bush to participate in the Ivy League command post exercise by flying in the NECAP, but Bush declined. There is no record of Bush flying in the E-4B NEACP while president, nor is there any record of his successor William J. Clinton doing so prior to the August 23, 1990, introduction into service of the Boeing VC-25A, which duplicated some of the NEACP’s command and control functions. In 1994, the E-4B NEACP was renamed the National Airborne Operations Center (NAOC), with its duties expanded to include support of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) responses to natural disasters and other non-nuclear crises.

In the absence of declassified official documents, it appears that under an extreme crisis, such as a nuclear or biochemical attack on the entire United States, the President and his NCA advisors would not become airborne in the traditional VC-25A, popularly referred to as Air Force One, but would instead relocate to the E-4B NAOC. This was apparently contradicted during the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center and Pentagon in 2001, when President George W. Bush remained aboard a VC-25A after stopping briefly at Offutt, where one E-4B was ready for his immediate use. Another E-4B was caught on camera launching out of Andrews right after the attacks, resulting in a rash of conspiracy theories, and yet another one was shortly airborne over the Midwest.

One can assume that Bush and his advisors determined that he did not require the full services of the NAOC and could continue using his VC-25A. This proved unwise, as there were reportedly significant constraints on the VC-25A’s communications that would have been alleviated by the E-4B’s suite.

Official records have not indicated that Presidents Barack H. Obama, Donald J. Trump, or newly elected Joseph R. Biden have flown in the NAOC. With the future of the E-4 up for grabs in the proposed Survivable Airborne Operations Center (SAOC), Biden or his successor may be the first to fly in the next generation of airborne command posts.

Robert S Hopkins, III, flew the RC-135S and RC-135X as a copilot from 1987-1990. In 1989, he was part of the crew that flew the first operational reconnaissance mission of the RC-135X, for which they became the first RC-135 crew to receive the General Jerome F “Jerry” O’Malley Award for the best reconnaissance crew in the Air Force. Hopkins has written extensively about the Cobra Ball and other RC-135 operations.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com