Some of the U.S. Air Force’s A-10 Warthog pilots are now training, in part, using a literal computer game, albeit a highly sophisticated and realistic one, known as Digital Combat Simulator World, more commonly referred to simply as DCS. The 355th Training Squadron at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona is using DCS together with commercially available virtual reality headsets and other gaming peripherals to provide a low-cost way of augmenting more traditional training regimens on the ground and in the air. This underscores the growing and at times controversial interest within the Air Force, as well as elsewhere across the U.S. military, in using VR to help expand training capacity and do so on the cheap.

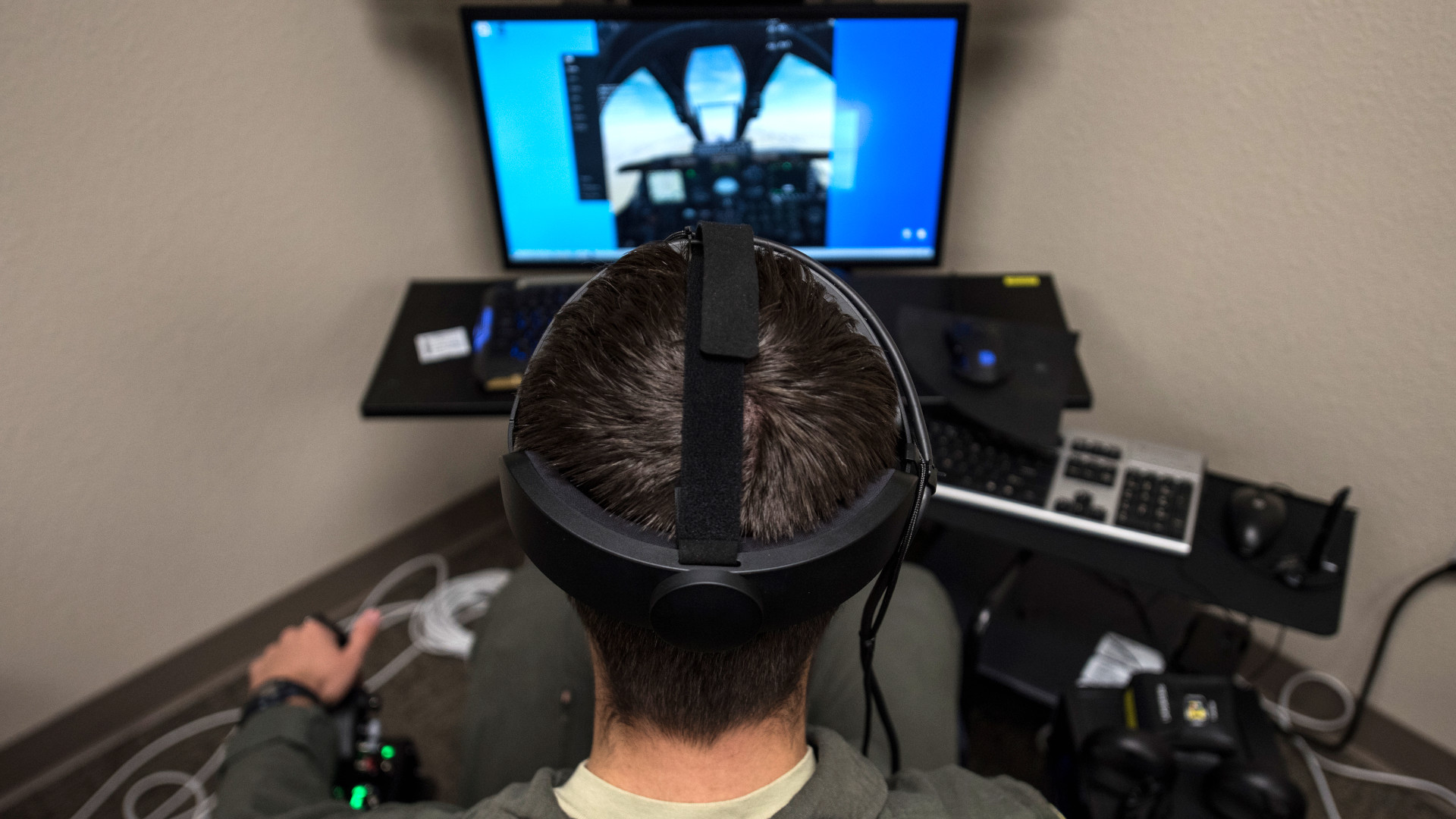

The 355th Training Squadron’s A-10 Simulator Laboratory has been using a staple of the flight simulator gaming world, including DCS, as well as Oculus Quest and Rift VR headsets, Thrustmaster HOTAS Warthog joysticks and throttles, and Thrustmaster TPR pendular rudder pedals. The computer workstations in the lab, from Volair Sim, are specifically designed for use together with flight simulator games and their associated peripherals.

The unit had begun the process of setting up this training lab back in 2018 and personnel subsequently used money from a fund set aside for “innovation” projects to procure the commercial off-the-shelf software and hardware.

Davis-Monthan is a major hub for Air Force A-10 operations and is presently home to three Warthog squadrons, two of which are combat-coded units assigned to the active-duty 355th Wing. The 45th Fighter Squadron, an Air Force Reserve squadron assigned to the 924th Fighter Group, is a dedicated Warthog training unit.

“VR has proven to be a tremendous tool for showing specific sight pictures that would otherwise be impossible to show via 2D pictures and traditional academic material,” a spokesperson for the 355th Wing told The War Zone, who also confirmed that technology was being used in conjunction with the DCS gaming software. “We are also using VR headsets for students to view 360-degree training footage, and communities all across the Air Force are starting to adopt similar platforms for multiple different career fields.”

In a video the Air Force released last year, seen below, Air Force Major Drew Glowa, a 355th Training Squadron instructor pilot, said that, prior to the establishment of the A-10 simulator lab, training for Warthog pilots on the ground at Davis-Monthan consisted only of a mix of “classroom instruction, computer-based training, and full-mission trainers.”

The FMTs are more traditional full-motion simulators where an individual sits inside a physical replica of the A-10 cockpit positioned in front of a large screen, onto which is projected a simulated environment. Whoever is “flying” the mock Warthog then goes about performing various simulated tasks with other personnel in an adjacent control center managing the entire scenario.

“We are using virtual reality simulation to provide an immersive trainer for students,” Air Force Major Drew Glowa, a 355th Training Squadron instructor pilot, had also said an interview for an official Air Force news item last year. “Training includes all aspects of operating the A-10 to include, but not limited to: ground operations, start-taxi-take offs, landings, formation flying, weapons employment, threat reactions, air-to-air refueling and other critical capabilities.”

“There are two distinct lines of effort in our VR program,” Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Tim Manning, the commanding officer of the 355th Training Squadron, added in a separate interview at that time. “First is the lab where students can fly the A-10 and practice tasks and the second, is having actual flights filmed in 360-degree video, viewed on VR headsets.”

The U.S. military’s use of computer and video games, or derivatives of them, for training purposes is hardly new. In 1996, the U.S. Marine Corps famously acquired a unique version of Doom II, the sequel to the equally iconic first-person shooter game Doom. Bohemia Interactive, best known for the Operation Flashpoint and Arma series of realistic military simulator games, has also supplied related software to the U.S. military.

The 355th Wing’s use of DCS for A-10-related training is hardly surprising given the extreme realism the game offers, as well as the fact that an official Warthog “module” had already been created for it and was just upgraded recently to offer even more ‘extreme fidelity.’ Most DCS aircraft models feature fully ‘clickable’ cockpits and extreme realism down to controlling the aircraft’s subsystems. Even starting an aircraft in DCS is nearly identical to doing so in reality.

Developed by Eagle Dynamics, which was founded in Russia, but now has its main headquarters in Switzerland, DCS was first released in 2008. DCS was an evolution of the earlier Lock On: Modern Air Combat (LOMAC) series. The underlying software is free to download, but the company sells modules for the game with new aircraft and other additional features. More than a decade on, new aircraft and more, as well as updates to existing content, are under development for this highly detailed combat flight simulator.

Calling DCS simply a game may be somewhat unfair given how realistic it is, especially when combined with a VR headset, as The War Zone

has noted in the past. Eagle Dynamics certainly has a commitment to authenticity and, two years ago, one of the company’s programmers actually found themselves in a jail cell in Utah after on charges of attempting to acquire sensitive flight manuals for the F-16 Viper and F-22 Raptor fighter jets in violation of U.S. arms exports laws. After his arrest, Oleg Tishchenko, a Russian national, said he needed the manuals for work, but Eagle Dynamics denied ever signing off on any plans of his to acquire the documents and insisted he was not involved in the development of the F-16 module for DCS. In June 2019, he was convicted of a number of charges, but sentenced to time served, immediately released, and deported.

Using DCS, “we can now demonstrate exactly what it looks like flying on the wing of a tanker and subsequently flying to the correct position behind it to refuel,” the 355th spokesperson told us an example of the training that is now available through the A-10 simulator lab. “Leveraging DCS’s impressive visuals in VR, we are able to have students fly and practice the correct positions themselves, which is very valuable training for a single-seat aircraft. No 2D screen can show the same level of depth perception required to accurately fly these types of close formations.”

“This prepares them for flying events better than any other training tool we have at a higher availability,” Major Glowa, the A-10 instructor pilot, said last year. “Now we can review specific tasks in a real-world environment by supplementing our four traditional simulator bays and giving students 22 more cockpits to practice on their own or with an instructor. We can expedite ground training to prepare students for flights at a pace we have never seen. We are transforming the way we train pilots and will be able to actually increase quality faster and add remedial training at almost any time. This will expedite the time it takes to get students ready for their flights.”

The ability to carry out this kind of training with a high degree of realism on the ground is especially important for A-10 units. There is no two-seat trainer version of the Warthog, which means that pilots who are new to the type have no alternative but to actually fly it for the first time solo.

The larger, more traditional FMT provides important simulated flight experience before then, but these are also limited in number and can be expensive to operate and maintain. As such, the A-10 simulator lab, through DCS and VR, also offers very low-cost additional simulator capacity.

“It’s always challenging for us with the three squadrons here to basically find time to make sure everyone’s got enough slots to get a certain amount of training done,” according to Major Glowa. “The biggest benefit for this is that you have a low-cost option to get students actually chair-flying realistic events and sight pictures that they’ve never had before.”

“You have to be able to practice like you play,” he added in the 2020 video interview. “The more we can do that, the more opportunities we have to train before we go fight the better, so this leverages that big time.”

The cost savings and added capacity that VR, in general, can offer have already made this an area of great interest across the U.S. military. The Air Force, in particular, has focused on leveraging VR for simulated ground-based flight training as one way to help generate sufficient numbers of new pilots, something the service has struggled to do in recent years.

The use of VR is already expanding into other kinds of training, too. Augmented reality (AR) is also emerging as another lower-cost avenue to provide additional training capacity.

The A-10 simulator lab isn’t even the only VR-based training going on at Davis-Monthan. The 355th Operational Support Squadron has also been using VR-based simulations to help train ground personnel to conduct various tasks.

“The 355 TRS [Training Squadron] is a key leader and trailblazer in this space and is leading the combat Air Force,” he added. “We have moved out on the Chief of Staff of the Air Forces’ message to ‘accelerate change or lose.'”

At the same time, there have already been criticisms leveled at the increasing use of simulated training, with some warning that this could leave new pilots with a worrying lack of actual flying experience. Lieutenant Colonel Manning, the 355th Training Squadron commander, spoke directly to those concerns last year.

“We are not cutting flights or flying hours in the syllabus, but instead we are using this technology to produce more lethal, efficient and safer A-10 pilots,” he said. “Better ground training methods will result in making the most of every flight hour. It also has the potential to be more cost-efficient for the Air Force, and maybe even a faster way to accomplish training.”

As Manning makes clear, VR training using software like DCS is not a substitute for real flight training. At the same time, it certainly opens the door to significant changes to how various portions of a larger flight training program are carried out. The War Zone‘s own Tyler Rogoway had similar observations in the past regarding how high-fidelity commercial flight simulators could be used to help with training, writing:

Nothing is like the real thing. No matter how good the sim is, it isn’t actually flying. But the fact that this level of technology is now available to the consumer means that a lot of the basics can be learned at home, in VR. From mastering core procedures, to working an aircraft’s avionics, to basic flying skills, they can be learned in your living room or in a nearby office building. Instructors can be right there to help guide a pilot’s skillset without even being in the same country.

The Air Force certainly appears to be continuing to refine how it uses commercially available VR, as well as things like DCS, to support its training requirements. At the same time, the experience of A-10 pilots assigned to the 355th Wing shows that there is a clear value, both in terms of cost and capacity, to expanding the use of this technology going forward.

With all this in mind, DCS users can feel even more confident in the game’s fidelity. If it is good enough for A-10 pilots to learn essential skills, it has to be pretty damn good.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com