The U.S. Army has finally provided an official range for its future Long Range Hypersonic Weapon, or LRHW. This range figure notably means it would have been prohibited under the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, that the United States and Russia were parties to until 2019. This disclosure also follows criticism earlier this year from a senior Air Force officer about the utility of this weapon, especially in the Pacific region.

“The Long Range Hypersonic Weapon provides a capability at a distance greater than 2,775 km,” an Army spokesperson said, according to Breaking Defense. This means that the LRHW can strike targets at least 1,725 miles away. For comparison, the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) short-range ballistic missile, the longest-range ground-based missile system currently in Army service, can only reach targets out to 300 kilometers, or close to 186 miles.

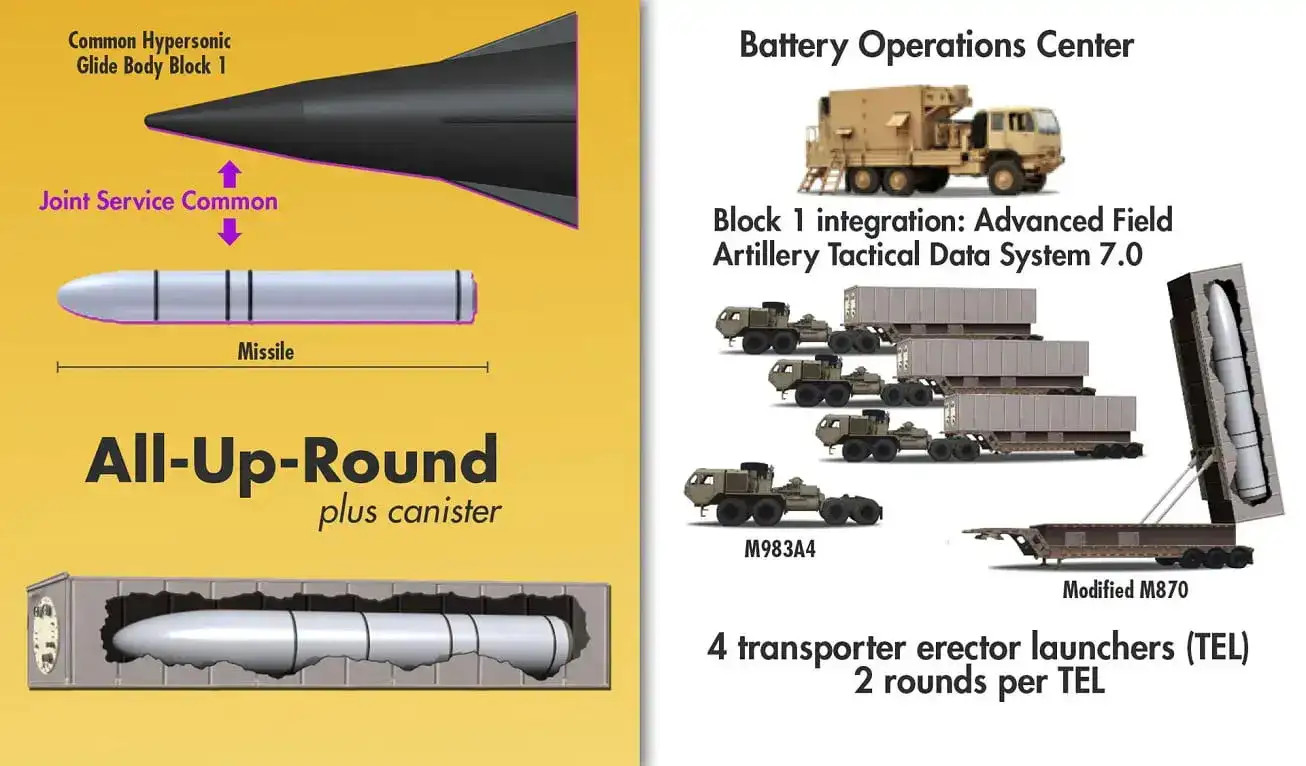

The complete LRHW missile consists of a large rocket booster with an unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle on top. The rocket is used to loft the conical boost-glide vehicle to a desired speed and altitude. The vehicle then detaches and comes zooming back down toward its target along an atmospheric flight trajectory at hypersonic velocity, defined as anything above Mach 5.

Hypersonic boost-glide vehicles are designed to have a high degree of maneuverability, especially compared to traditional ballistic missiles, even those with advanced maneuverable reentry vehicles. This makes them ideal for striking time-sensitive or other high-value targets protected by dense enemy air and missile defenses and doing so on short notice, even at extended ranges. The combination of speed and maneuvering makes it very difficult for opponents to spot and track these weapons, let alone try to defend against them, including just trying to relocate critical assets or otherwise seek cover.

It had first emerged in 2018 that the Army, together with the U.S. Navy and Air Force, were working together on a tri-service hypersonic weapons program. LRHW is the Army’s component of this program, while the Navy’s portion is known as the Intermediate-Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IRCPS) system. Last year, the Air Force announced that it was abandoning its segment, the Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW) program, in favor of the AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW), which uses a wedge-shaped boost-glide vehicle.

The LRHW and IRCPS systems both use the same core missile and boost-glide vehicle, but are being adapted for launch from ground-based and naval platforms, respectively. Details have been slowly trickling out about this joint-service hypersonic weapon in recent years, but, as already noted, the statement to Breaking Defense is the first time an actual official range has been given.

The figure is immediately interesting in the context of the INF treaty, which had prohibited the United States and Russia from deploying nuclear or conventionally-armed ground-based cruise and ballistic missiles with ranges between 310 and 3,420 miles. The Army withdrew its nuclear-armed Pershing II medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBM), which had a maximum range of around 1,100 miles, from service as a result of that deal. The last of these missiles were decommissioned in 1991.

With all this in mind, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the weapon’s range has been kept under wraps for so long. The U.S. government, under President Donald Trump, only formally withdrew from the INF in 2019, ostensibly over Russia’s fielding of a prohibited ground-based cruise missile system, something the Kremlin continues to deny it has done. At that point, work on at least the underlying components of the LRHW had been going on for years. In 2017, the Navy even conducted the first flight test of what subsequently emerged was a common boost-glide vehicle design, launching it from an Ohio class submarine. The INF did not place any limitations on the development or fielding of ship- or submarine-launched cruise or ballistic missiles.

In 2017, reports also emerged that the United States had begun at least exploring the development of an INF-busting missile in response to Russia’s treaty-violating cruise missile. The INF did not expressly ban the research and development of ground-based weapons with prohibited ranges, providing no actual tests were carried out and that no such weapon was actually fielded.

It’s also interesting to note that the Navy consistently describes its version of this weapon, which, again, will use the exact same core missile packaged for launch from submarines and ships, as being “intermediate range.” Intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM) are defined as having maximum ranges between 1,864 and 3,418 miles, the lower end of which is still greater than the 1,725 miles figure that the Army has now provided for LRHW.

LRHW is also just one of a number of post-INF land-based missiles that the Army, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps, is now pursuing. Both services are looking at the possibility of fielding ground-launched versions of the Tomahawk cruise missile. The INF had led to the scrapping of a previous land-based Tomahawk variant, the BGM-109G Gryphon, which had been in service with the U.S. Air Force.

The Army is also developing a replacement for ATACMS, the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM), the range of which is no longer limited by that treaty. Just yesterday, Lockheed Martin announced that it had demonstrated the ability of that weapon to hit targets out to nearly 250 miles and there has already been talk of pushing that out further to somewhere between 340 to 372 miles.

There is also another ground-based hypersonic weapon program, Operational Fires (OpFires), that the Army is working on, together with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The OpFires missile also carries an unpowered boost-glide vehicle and it is unclear exactly how this weapon differs from the LRHW design.

The disclosure of the LRHW’s range now is also not entirely surprising. While a guest on an episode of Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute’s Aerospace Advantage podcast in March, Air Force General Timothy Ray, head of Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC), said, in no uncertain terms, that he felt the LRHW program was “stupid.” Ray was especially critical of the weapon’s utility in the Pacific, where a number of American allies, including Australia and South Korea, have already said they have no interest in hosting them. There have been reports that Japanese authorities could be inclined to allow future Army missile units onto its soil, possibly through rotating deployments.

“There are a lot of countries that have to agree to this. I could see some of them probably agreeing in the European theater, maybe in the Central Asian theater, but I don’t see it coming together with any credibility in the Pacific any time real soon,” Ray said. He also touted the Air Force’s own work on the ARRW program, as well its experience with the kinds of long-range bomber operations into which those weapons are expected to be integrated, including in the Pacific.

Ray’s comments ultimately led to a meeting between the Army and Air Force chiefs of staff and prompted public statements of support for the LRHW from other senior U.S. military officials. Land-based hypersonic weapons, as well as other ground-launched longer-range missiles, are a core component of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI) concept that the U.S. military has proposed as a way to counter China in that region, which you can read about more in detail here.

As Breaking Defense pointed out, with a range of 1,725 miles, LRHWs fired from the U.S. island of Guam, where the weapons would be based without any need for foreign consent, could reach Taiwan. This would allow their potential use in response to a Chinese invasion of that island. Officials in Beijing see that island, which presently has a completely autonomous government, as an integral part of China and they routinely threaten to use military force should authorities in Taipei declare full independence from the mainland.

LRHWs capable of striking targets 1,725 miles or more away would be able to reach deep inside the Chinese mainland if they could be positioned in Japan, or the Philippines, another country that has come up in discussions about basing these weapons. Having these missiles in Japan would also mean they could prosecute targets in North Korea or Russia’s Far East region.

“You might aggregate Navy and Army; you might aggregate Air Force and Army, but if someone shows up to the battle and they don’t have long-range fires and the adversary does, you can’t effectively operate in that theater,” Air Force General John Hyten, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said in April, speaking about future operations generally. “This means you want each service to bring those long-range fires; so, the joint warfighting concept succeeds if all of the force can apply fires wherever they happen to be, wherever the target is, whatever the lines of conflict, that is the joint warfighting concept.”

All this being said, budgets are likely to be a key factor in any future discussions about Army ground-based hypersonic or other longer-range missile capabilities. The Air Force notably abandoned HCSW, its companion to the LRHW/IRCPS program, in order to refocus resources on the ARRW project.

As it stands now, the Army hopes to have a prototype battery ready to begin live-fire testing of the LRHW sometime in the 2022 Fiscal Year. That unit is then expected to form the core of a limited operational capability with this weapon in the next fiscal cycle.

By disclosing the LRHW’s range, the Army seems to be making a new pitch for that weapon’s place in the future mix of long-range strike capabilities across the U.S. military. In doing so, the service has also made clear that the U.S. military has now left the limitations that the INF treaty had imposed far behind.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com