The U.S. government and defense contractor Honeywell have reached a settlement over alleged violations of portions of the Arms Export Control Act, or AECA, and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR. The matter at hand had to do with Honeywell’s alleged unauthorized export of dozens of technical drawings relating to components of various aircraft, missiles, and tanks, including the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the F-22 Raptor stealth fighter, the B-1B bomber, the Tomahawk cruise missile, and the M1A1 Abrams, to multiple countries, including China. American officials contend that some of the disclosures harmed national security, something that Honeywell denies.

The U.S. State Department announced the deal, in which Honeywell agreed to pay $13 million in civil penalties, among other things. Of that amount, the payment of $5 million was immediately suspended on the condition that the company put it toward “remedial compliance measures.” In addition, the U.S. government chose not to pursue more serious action based on Honeywell “voluntarily” disclosing the exports that violated the AECA and ITAR, which the State Department also continues to describe as alleged as a result of the settlement.

“The settlement demonstrates the Department’s role in strengthening U.S. industry by protecting U.S.-origin defense articles, including technical data, from unauthorized exports,” according to a press release from the State Department. “The settlement also highlights the importance of obtaining appropriate authorization from the Department for exporting controlled articles.”

“Honeywell voluntarily disclosed to the Department the alleged violations that are resolved under this settlement. Honeywell also acknowledged the serious nature of the alleged violations, cooperated with the Department’s review, and instituted a number of compliance program improvements during the course of the Department’s review,” according to that statement. “For these reasons, the Department has determined that it is not appropriate to administratively debar Honeywell at this time.”

The charging document in the case, now made public through the State Department’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls, says that “Honeywell ultimately identified 71 ITAR-controlled drawings that between July 2011 and October 2015 it had exported without authorization,” in a disclosure it voluntarily made in 2016. Two years later, the firm acknowledged a second set of unapproved exports “that were similar to the violations disclosed in the first voluntary disclosure,” according to the State Department.

All of these alleged exports had to do with drawings that “contained engineering prints showing layouts, dimensions, and geometries for manufacturing castings and finished parts for multiple aircraft, military electronics, and gas turbine engines” used on various aircraft and ground vehicles. The documents were shared via DEXcenter, “a file exchange platform” that the Honeywell employees in question typically use to “transfer drawings to suppliers.”

That document includes the following list of impacted platforms, with a caveat that this was only some of the examples, rather than a full accounting:

- F-35 Joint Strike Fighter

- B-1B Lancer Long-Range Strategic Bomber

- F-22 Fighter Aircraft

- C-130 Military Transport Aircraft

- A-7H Corsair Aircraft

- A-10 Aircraft

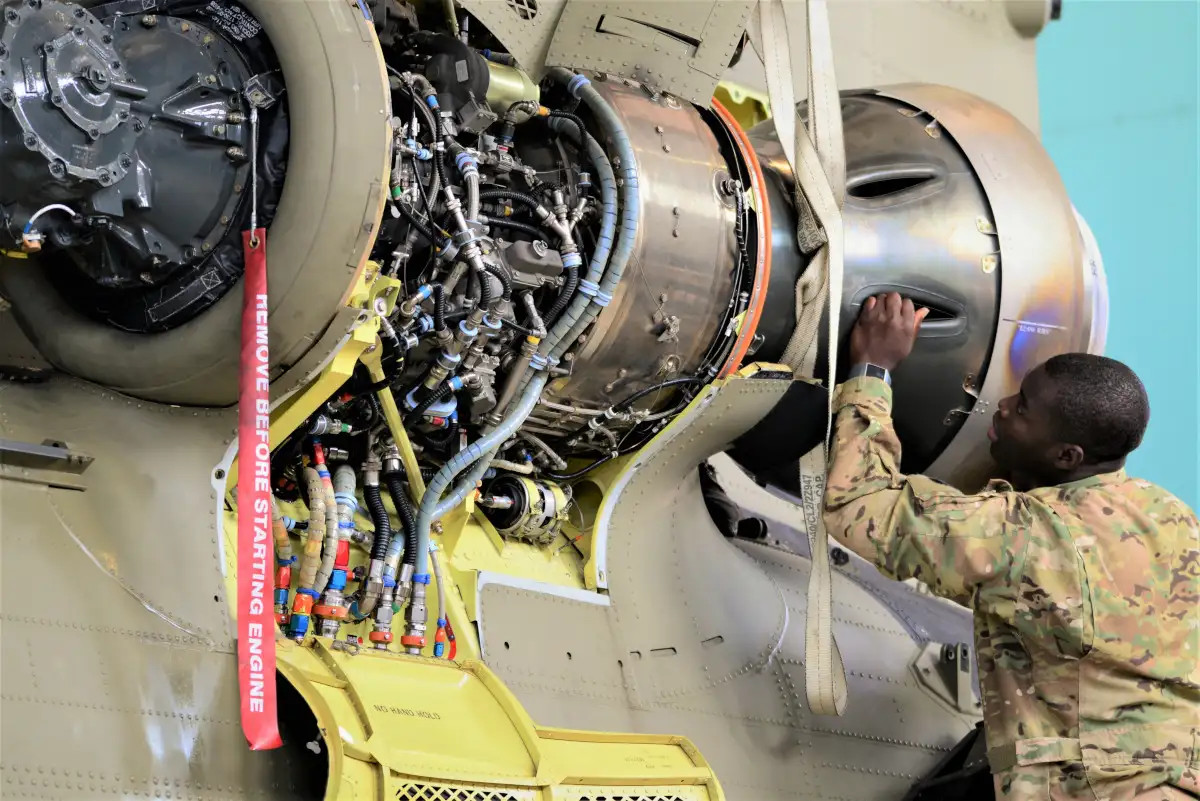

- Apache Longbow Helicopter

- M1A1 Abrams Tank

- Tactical Tomahawk Missile

- T55 Turboshaft Engine

It’s worth pointing out that the A-7H was a variant of the A-7E developed specifically for Greece’s Hellenic Air Force and that the Corsair II series, as a whole, has been out of U.S. military service now for decades. The Greeks formally retired the last of their A-7s in 2014.

Variants of the T55 turboshaft engine have been used on platforms over the years, most notably the CH-47 Chinook series of helicopters. The Boeing Sikorsky SB>1 Defiant advanced compound helicopter now under test by the U.S. Army also uses versions of the T55.

Honeywell is alleged to have made unauthorized exports of drawings related to components “that are used in platforms including in the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, M1A1 Abrams Tank, Tactical Tomahawk Missile, B-1B Lancer Long-Range Strategic Bomber, and F-22 Fighter Aircraft platforms as well as the T55 and CTS800 turboshaft engines to the PRC [People’s Republic of China],” specifically, according to the State Department. “The U.S. Government reviewed copies of the 71 drawings and determined that exports to and retransfers in the PRC of drawings for certain parts and components for the engine platforms for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, B-1B Lancer Long-Range Strategic Bomber, and the F-22 Fighter Aircraft harmed U.S. national security.”

The CTS800 engine, not mentioned in the earlier list, was originally designed to power the RAH-66A Comanche stealth helicopter. Today, it is found in the Leonardo AW159 Wildcat helicopter, used by the U.K. Royal Navy, among others, and the Turkish T129 ATAK attack helicopter, among others.

Additional alleged unauthorized exports of drawings were made to Canada, Mexico, Ireland, and Taiwan. However, the U.S. government did not assess any of these incidents to have directly impacted national security, according to the charging document.

Honeywell has disputed the national security implications of the transfers, which it first disclosed to the U.S. government in 2018.

“The issues Honeywell reported involved technology that was assessed as having no impact on national security and is commercially available throughout the world,” the company said in a statement. “No detailed manufacturing or engineering expertise was shared.”

It is also worth noting that the provisions of the AECA and ITAR are extremely stringent. They even place serious penalties on the foreign export of seemingly innocuous items, such as certain unclassified technical manuals that can otherwise be freely bought and sold by U.S. citizens.

At the same time, even if details about the core technology in question are freely available internationally, it seems hard to see how exporting drawings that could relate to the use of said technology on sensitive platforms, such as the F-35, F-22, B-1, or Tomahawk cruise missile, would not be at least concerning.

The Chinese government has a long history of conducting industrial espionage with the aim of acquiring various military and commercial technology, especially aviation-related systems, with a particular focus on aircraft engines. In 2018, U.S. and Belgian authorities notably worked together to apprehend a Chinese spy accusing of stealing aerospace information from various American firms, including General Electric. The country’s intelligence services have already obtained other more sensitive information about various modern American weapon systems, including the F-35 and F-22, as well.

“In my discussions — in my discussions with President Xi, I told him, ‘We welcome the competition. We’re not looking for conflict,'” President Joe Biden said last week, referring to Chinese President Xi Jinping, in an address to a joint session of Congress on April 28, 2021. “But I made absolutely clear that we will defend America’s interests across the board. America will stand up to unfair trade practices that undercut American workers and American industries, like subsidies from state — to state-owned operations and enterprises and the theft of American technology and intellectual property.”

It’s certainly possible, now that this settlement is public, that more information about the specifics of what was allegedly exported and the operational security issue at play may now emerge. Whatever the case, the alleged violations are certainly disconcerting given the lengths Chinese authorities are known to go to secure similar information illicitly.

UPDATE, 5/4/21:

After the publishing of this story, Honeywell reached out, saying the initial company statement that had been sent out contained errors and to provide an updated statement, which is as follows:

Honeywell is fully committed to compliance with all applicable export control laws, including International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). Several years ago, we voluntarily informed the U.S. Department of State’s Defense Trade Controls Compliance (DTCC) unit in two Voluntary Disclosures where Honeywell designs were inadvertently shared during normal business discussions.

The issues Honeywell reported involved technology that was assessed as having an impact on national security, though is commercially available throughout the world. No detailed manufacturing or engineering expertise was shared.

Under an agreement reached with the State Department to resolve these issues, Honeywell will pay a fine, engage an external compliance officer to oversee the Consent Agreement for a minimum of 18 months, and will conduct an external audit of our compliance program. Since Honeywell voluntarily self-reported these disclosures, we have taken several actions to ensure there are no repeat incidents. These actions included enhancing export security, investing in additional compliance personnel, and increasing compliance training.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com