The U.S. military has confirmed that the secretive Joint Special Operations Command, or other U.S. government entities operating in cooperation with it, has been flying a new type of drone in the Middle East that is designed to be extremely quiet and have an innocuous outward appearance. The new details about the Long Endurance Aircraft Program have come to light after one of these unmanned planes, derived from the Pipistrel Sinus powered glider, crashed at Erbil International Airport in Iraq last year.

The Long Endurance Aircraft Program (LEAP) drone in question, identified only as AV009, crashed at Erbil on July 24, 2020, according to a heavily redacted copy of the official accident report that The War Zone obtained via the Freedom of Information Act. The unmanned aircraft suddenly and unexpectedly pitched nose down while coming in to land at the airport after a sortie. The drone hit the ground, bounced back up into the air, and then came back down, eventually coming to rest alongside the runway. The mishap resulted in the front-mounted propeller striking ground and the landing gear collapsing. It also caused significant enough damage to the right wing that fuel leaked onto the ground.

The immediate cause of the accident and any associated factors, as well as any details about recommended disciplinary action or changes to tactics, techniques, and procedures made in light of the mishap, are entirely redacted. The report does mention poor weather over Erbil, as well as an unspecified mission area, during the sortie. The Air Force said that aircraft, valued at $3.4 million, was a “total loss.”

Air Force Magazine

had been first to disclose that a mishap involving what was then described as an unidentified “remotely piloted vehicle,” or RPA, had occurred at an “undisclosed location” overseas on July 24, 2020. That outlet had obtained a spreadsheet of all Class A and B mishaps the Air Force had suffered during the 2020 Fiscal Year, which ended on Sept. 30, 2020. There had been speculation at the time that the crashed drone could have been an RQ-170 Sentinel, though the spreadsheet said that the unmanned aircraft belonged to Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC). Units assigned to Air Combat Command (ACC) are the only ones publicly known to fly the stealthy RQ-170.

The official accident report does not provide a detailed description of the LEAP aircraft, but does say that at least this particular example was government-owned and contractor-operated at the time of the incident. The document also identifies the individual who was operating the drone during the mishap as an employee of Technology Service Corporation (TSC). The Pentagon announced on April 14, 2020, that SOCOM had raised the cost ceiling on an existing contract with TSC to support the LEAP, which “provides aircraft, turrets and spares required for a full multi-intelligence capability at Joint Special Operations Command [JSOC],” to $63 million. In February of this year, that ceiling was again increased, to $75 million, “to accommodate a longer performance period.”

In December 2019, the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) had also announced that its Center for Rapid Innovation had completed a series of flight tests at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah in support of what was referred to as the Ultra Long Endurance Aircraft Platform (Ultra LEAP) program. That testing ended with “a two and a half-day continuous flight demonstration” of a “high-performance, cost-effective, sport-class commercial airframe converted to a fully automated system with autonomous takeoff and landing capabilities.”

AFRL said at the time that “the system could be ready for operational fielding as soon as 2020.” The Air Force said it had only taken 10 months to go from “concept to first flight” and that the “high level of automation” would simply operator training and logistics support requirements, as well as help keep operating and maintenance costs low.

“U.S. Special Operations Command’s long-endurance aircraft program includes Pipistrel Sinus aircraft converted by the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory into an unmanned aerial system,” U.S. Navy Commander Tim Hawkins, a SOCOM spokesperson, subsequently confirmed to The War Zone. “SOCOM has been assessing this platform as an option as we work with our military services and industry partners to identify low-cost, high-endurance airborne intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance solutions. This unmanned aerial system is contractor-operated and has a payload that includes a combination of full-motion video and signals intelligence sensors.”

The original Pipistrel Sinus design dates back to the mid-1990s and numerous subvariants, including easier-to-store versions marketed as the Virus line, have been produced since then. The company, which has its main headquarters in Slovenia, says that the current Sinus 912 model has a maximum speed of just under 137 miles per hour, has a cruise speed closer to 124 miles per hour, and has a stall speed of just under 40 miles per hour with its flaps deployed.

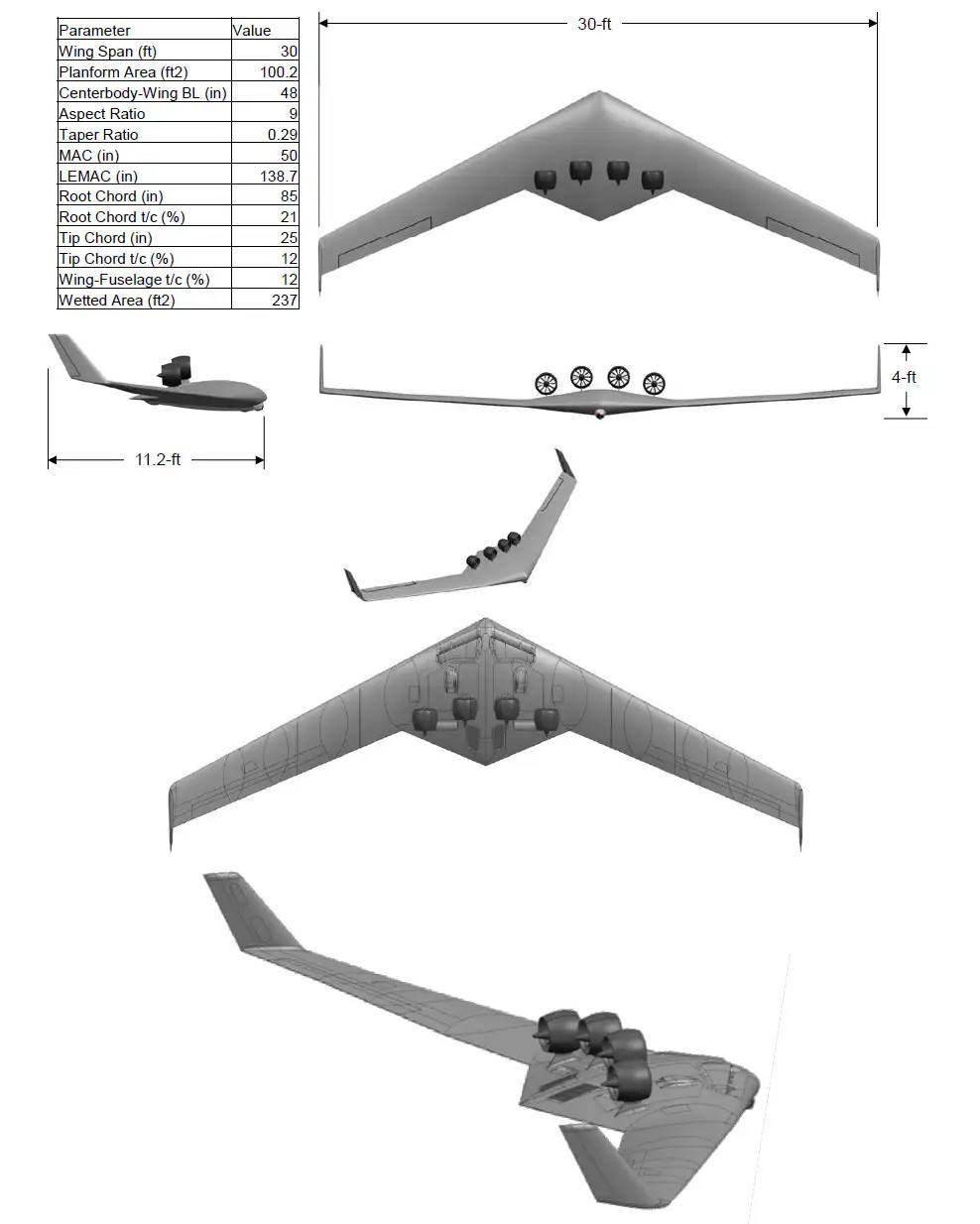

Beyond details about its endurance, there are very limited specifics about the U.S. military’s LEAP derivative and its configuration. An artist’s conception that AFRL released in 2019 shows a substantially different planform with no traditional cockpit and an even longer and more slender wing than is seen on a typical Sinus. It also has no visible landing gear suggesting the LEAP design has retractable undercarriage or other means of recovery, unlike the Sinus.

“The Air Force research laboratory (AFRL) has demonstrated the suitability of Pipistrel light aircraft for SOCOM, installing sensors to collect full motion video, lidar [light detection and ranging] and signals intelligence with many units already deployed and operating around the globe,” Pipistrel’s subsidiary in the United States, Pipistrel-USA, disclosed last year. LIDAR provides a laser imaging capability that can also reveal objects that might be buried at certain depths beneath the ground, such as improvised explosive devices or weapons caches.

Pipistrel is also now marketing an unmanned derivative of its Surveyor aircraft, which is related to the Sinus design, for military use. The company says this drone can fly at altitudes up to 30,000, remain aloft for up to 30 hours, and cover a total distance up to nearly 2,800 miles, depending on payload, altitude, mission profile, and other factors.

SOCOM would not provide any details about what unit or units are operating these drones or how many it has in inventory. The official accident report identified AFSOC as the “owning MAJCOM [major command]” for the LEAP drone and Hurlburt Field in Florida as the “owning base.” Interestingly, however, it said that the “owning service” for the associated ground control station was an “Other US Govt Agency (Federal, State or Local).” The term “other government agency,” often abbreviated OGA, is typically used by elements of the U.S. military to refer to entities outside of the Department of Defense, particularly the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Reports over the years have provided significant evidence of a very close working relationship between JSOC, and units tasked with supporting its operations, and the CIA, especially when it comes to unmanned aircraft. In addition, it is known that highly secretive SOCOM aviation elements have supported JSOC operations from Erbil in the past.

It’s not clear exactly where the LEAP aircraft that crashed last year had been flying before the mishap, though the accident report says that it had completed an orbit lasting between 7 and 10 hours. The operator had asked about retasking the drone to another area before the decision was made to bring it back to Erbil. It’s also unclear if LEAP drones have or may still be operating from any other locations in the Middle East or elsewhere around the world.

It’s also not entirely clear how long JSOC has been flying the LEAP drones, or any manned, unmanned, or pilot-optional predecessors based on Pipistrels designs. Despite AFRL’s press release talking about fielding the unmanned aircraft in 2020, the mishap report says that the example that crashed in Iraq had been modified in January 2019, then performed five test and checkout flights at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, and then subsequently deployed to Erbil in March of that year.

In May 2020, Pipistrel-USA revealed in an edition of its official company newsletter that contractors had been operating unmanned Surveyor aircraft in support of SOCOM since 2013. This public disclosure was made, in part, in response to uncertainty about SOCOM’s Armed Overwatch program, which is seeking a manned light attack aircraft to replace Air Force Special Operations Command’s (AFSOC) U-28A Dracos, and SOCOM’s interest in lower-cost alternatives to the MQ-1C Gray Eagle and MQ-9 Reaper.

“Budget constraints in the armed overwatch program have opened the way for evaluation of different lower-cost platforms,” Pipistrel-USA’s newsletter read. “On 13th of May as part of the virtual Special Operations Forces Industry Conference where Colonel Melissa Johnson, the program executive officer for fixed wing aircraft acquisition, showed a picture of an operational Pipistrel Surveyor aircraft on a presentation slide adjacent to the Gray Eagle and Reaper aircraft. As part of the presentation, Johnson told the audience of industry attendees that SOCOM is actively seeking new, low-cost alternatives to the MQ-1 and MQ-9 for long endurance surveillance missions. We beleive [sic] this is the first public acknowledgement of the Pipistrel surveyor program existence by SOCOM.”

From a budgetary perspective, the LEAP aircraft definitely appears to present a lower-cost alternative to existing unmanned aircraft. In March, the Air Force announced it had awarded General Atomics a contract to build a single MQ-9 for the U.K. Ministry of Defense at a cost of nearly $13 million as part of a Foreign Military Sales (FMS) arrangement. That figure also included various sensors, but it’s not clear if any other ancillary costs might have been factored in. Still, that price point is nearly four times the stated value of the LEAP aircraft that smashed into the runway at Erbil.

With all this in mind, it’s also possible, if not plausible that the drone that AFRL described last year as the Ultra LEAP is an improved variant or derivative of prior unmanned Pipistrels that JSOC has been using for years now.

Regardless, based on what we know about this program, overall, it’s not hard to see why JSOC, as well as other “OGAs,” would be interested in this drone. A highly efficient unmanned aircraft able to loiter over a particular area for a protracted period of time, but also with a low acoustic signature and a planform less likely to arouse suspicion if it is detected, offers clear benefits, especially for monitoring the activities of specific individuals or small groups and helping to establish so-called “patterns of life.” Pictures and videos of more traditional drones, such as MQ-9 Reapers, routinely appear on social media, showing that it is relatively easy to identify those aircraft, particularly when they have to fly at lower altitudes.

“They are very quiet, more that [sic; than] 50% quieter than a normal small aircraft,” Pipistrel says in its own brochure for the unmanned version of the Surveyor. “In the air, they look like an inconspicuous sport/recreational aircraft and they are not treated suspiciously.”

“They can be easily dismantled in less than 15 minutes and stored in a dedicated trailer,” that document adds. “Therefore, a hangar is not needed, and a regular vehicle can tow the aircraft in the trailer, no special transport is needed.”

This would also make it easy to deploy and operate these drones very discreetly, even from austere locations with limited infrastructure. “They can take-off and land on grass or unprepared surfaces, not just hard runways,” the unmanned Surveyor brochure also notes.

This is hardly the first time the U.S. military, as well as the CIA, has investigated similar capabilities. The LEAP aircraft, as it is understood now, sounds very much like a spiritual successor to the Vietnam War-era YO-3A Quiet Star and the RG-8A Condor that flew during the latter stages of the Cold War. These were manned aircraft designed with a particular focus on extremely low acoustic signatures.

The U.S. Army flew both the YO-3A and the RG-8A, and subsequently passed examples of the latter type to the U.S. Coast Guard. The CIA also reportedly operated some RG-8As, or other derivatives of the base Schweizer 2-37 powered glider design, including over Somalia, as both intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms (ISR) and communications relay nodes. The Coast Guard, as well as the Department of Justice, also flew RU-38A Twin Condor ISR aircraft, another militarized Schweizer design with a low acoustic signature. You can read more about all of these aircraft, as well as the Coast Guard’s abortive attempt to acquire a new Manned Covert Surveillance Aircraft (MCSA), an effort that spanned from the mid-2000s to the early 2010s, in this past War Zone feature.

It’s also worth remembering that, in 2017, a contractor-operated Grob G 520 configured for ISR missions appeared at an airport in Indiana around the time that U.S. special operations exercise was taking place. This aircraft is another slender-wing design optimized for high-altitude operations. Though it’s not clear if it has features specifically to reduce its acoustic signature, the manufacturer says on its website that the latest G 520NG model has a “very low probability of intercept.” This particular plane’s composite structure would also help reduce its radar signature.

The U.S. military, as well as the U.S. intelligence community, has also long been interested in unmanned aircraft with very low acoustic signatures and/or designed to be innocuous-looking from the outside. One particularly good recent example is the ultra-quiet, high-efficiency XRQ-72A, which Scaled Composites, a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman, developed as part of the Great Horned Owl program. The Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency (IARPA) led this project, which was first publicly announced in 2011 and that you can read about in much more detail here, in cooperation with AFRL.

The CIA’s Cold War-era Aquiline project is another prime example. Aquiline sought to develop a bird-shaped drone with extremely long-range, potentially powered, in part, by a nuclear battery, for discreet surveillance deep inside denied areas within the Soviet Union.

These are just some of the low-acoustic-signature drones that are known about, not to mention developments that are almost certainly occurring in the classified realm. Various companies market many of these designs publicly, in part, around how quiet they are, just as Pipistrel is doing with its militarized unmanned Surveyor.

These drones have come in various shapes and sizes, too, beyond types that are the size of small planes, or simply converted from them, such as the LEAP aircraft. These include relatively small catapult and hand-launched designs, such as the Lockheed Martin Stalker, which SOCOM reportedly bought some of in 2006, and that company’s more recent Fury propeller-driven, flying-wing unmanned aircraft.

Unmanned variants and derivatives of the Pipistrel can now be added to the list of such designs that have been used by the U.S. military operationally. Information about these drones is trickling out and, with the public acknowledgement of the loss of one of these discreet drones in Iraq last year, perhaps more details about how they have been employed will now begin to emerge.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com