The U.S. Air Force has, for the first time, live-streamed data directly from the F-35A stealth fighter and onto a commercial computer tablet in the cockpit, during ground tests at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. The March 31 trial, part of the Fighter Optimization eXperiment, or FoX, demonstrated that data from the jet could be used to communicate with mobile apps running on the tablet and there are hopes that the same concept could be used in the future on other manned fighters, as well as drones.

In the initial trial, the flight test instrumentation system was streamed from the F-35’s onboard systems and onto the tablet, on which apps were running. The first two such apps, developed under Project FoX, are designed to help the pilot of the stealth jet negotiate hostile air defense systems, and to use artificial intelligence (AI) to combat the same types of threat.

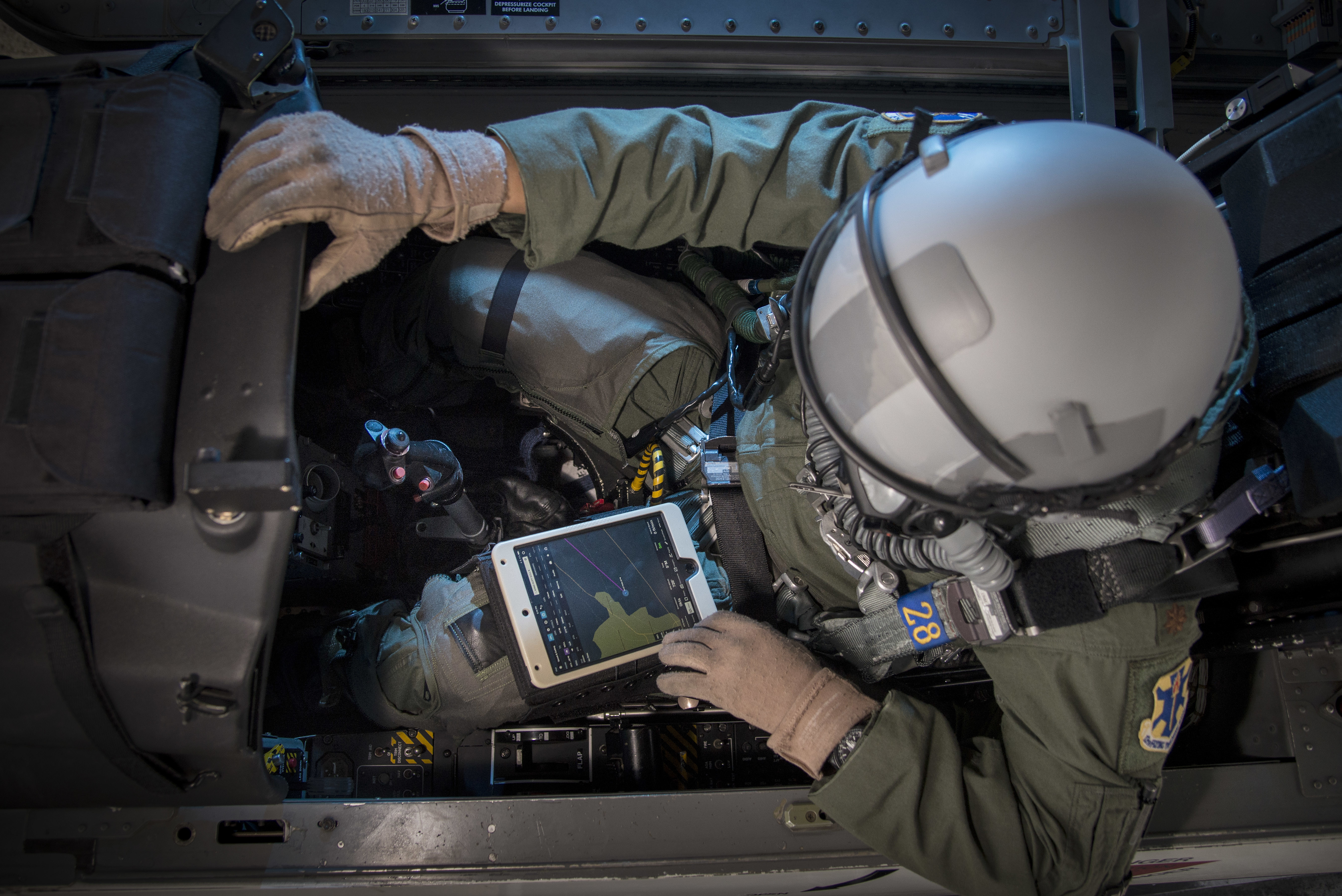

Until now, although F-35 pilots regularly fly with a tablet on their knee, these haven’t been fully integrated with the cockpit and were not able to be physically plugged into the jet and receive real-time data from its own mission computers and its hugely powerful sensor suite. Now, as well as at Nellis, F-35s at Edwards Air Force Base and at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, both in California, are also trialing the FoX Tablet interface. So far, the work had only been conducted with the jets on the ground but, once safety and security aspects are addressed, they will be used in the air, too.

The first of the apps being run on the F-35’s FoX Tablet is the Battlefield Management Portal, which provides the pilot with surface-to-air threat information “in a new format designed to maximize pilot effectiveness in the suppression of air defenses [SEAD] mission.“

The second app, developed by Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Development Programs branch, uses AI to “increase the F-35’s advantages against advanced surface-to-air threats.“

Previously, this type of information would be presented to the F-35 pilot on the all-glass touchscreen display, which can be customized to present different data, and via the helmet-mounted sight. Both have been the subject of various criticisms in the past, with pilots, for example, pointing to the apparent high degree of latency in information reaching the helmet, which has also been compared unfavorably to a traditional head-up display. The touchscreen doesn’t have any tactile feel or feedback, which can make tapping-in commands a bit challenging during certain environmental and combat conditions.

Even with these existing cockpit interfaces working seamlessly, there is still an argument to be made for having an additional source of situational awareness (SA), especially for the demanding SEAD mission, or other highly complex roles that the F-35 is increasingly finding itself used for, in the form of a tablet. A tablet is portable and, thanks to apps, can present a different tactical picture, or data set, than the other displays. Indeed, tablets are now a frequent fixture in the cockpits of — typically older-generation aircraft — to provide, for example, a means of displaying targeting pod data, or datalink-provided tactical and SA information, as well as flight manual and procedural info.

As mentioned at the top of this article, while Project FoX is being tested now with the F-35, there are plans for it to be migrated to potentially all U.S. military aircraft, both for use in combat missions and for development and test work. Since Project FoX is intended to insert advanced software and hardware quickly, it could play a big role in Air Force and Navy plans to develop new fighter aircraft and supporting systems, at a rapid pace.

That fact that speed is of the essence in what the Project FoX hopes to achieve was reinforced by Lieutenant Colonel Raven “Rost“ LeClair, a test flight commander stationed at Edwards and an F-35 command chief instructor test pilot: “We are trying to find ways to go faster for less money, to bring more capability per dollar, and to push more capabilities to the warfighter more quickly… We want to shift timelines from capabilities being fielded in years to being fielded in a matter of months or weeks; both hardware and software.”

While we often think about the F-35 in terms of its bleeding-edge cockpit interface and integrated avionics architectures, the fact is the technologies involved are no longer the latest and greatest, and actually tinkering with the software for an upgrade, for example, is not necessarily straightforward. Part of that is due to the way the Joint Strike Fighter has been talked about — and marketed. At one time, it was confidently predicted the F-35 would be able to have new software updates downloaded automatically, allowing new capabilities to become reality very quickly.

The realization that the F-35 is not the same as an iPhone seems to have helped driven Project FoX. The initiative started life at the 461st Flight Test Squadron’s (FLTS) Future Technology Team and, according to an Air Force news release “was formed with the mission of pursuing advanced aerospace technology and rapid innovation for the F-35… after identifying capability gaps between the vision for agile software development and reality.”

For the F-35, at least, while an integrated, missionized tablet offers all kinds of SA advantages for pilots flying into future battlespaces, it is likely that, at the beginning, Project FoX will be a tool to smooth the testing and fielding of new capabilities, such as the forthcoming Block 4 software package. This promises to enable enhanced radar and electronic warfare capabilities, as well as the ability to carry new weapons.

And beyond the Joint Strike Fighter, the Project FoX team is hopeful that the technology developed will filter down not only to other aircraft, but should “eventually optimize capabilities for every DoD platform through state-of-the-art methods, combat autonomous toolsets, and hardware and software solutions.”

That sounds incredibly ambitious, but combining the cockpit-integrated tablet with a “DoD Combat App Store” could be the way to achieve it, borrowing concept and terminology from the commercial sector. Ultimately, an app developed to help an F-35 pilot fly a SEAD mission could be downloaded onto a tablet used by an EA-18G Growler pilot, or the pilot of any other relevant platforms, including training assets, for that matter.

“There is no reason why I can’t test the same capability and app on F-18 before F-35 or risk reduce software on F-35 for use by unpiloted aircraft,” LeClair explained. “By connecting a tablet to an aircraft’s data bus, the warfighter and tester will be able to utilize an entire DoD Combat App store of tools, customized to help solve tactical problems in real time.”

“It also opens up a whole new world of opportunity for live-fly modeling and simulation,” LeClair added. “We will be able to find software bugs that escape the lab sooner and fix them faster, rapidly integrate AI tools that could never be run on the actual aircraft due to hardware limitations, provide unprecedented cyber-attack awareness and protection, and crowdsource testing on multiple platforms.”

Returning to the smartphone analogy, Lieutenant Colonel James Valpiani, 461st’s commander and F-35 integrated test force director, explained that the jet “has tens of millions of lines of code. And, of course, it’s different than an iPhone or Tesla in that people are trying to shoot it down. It is a very complex aircraft with a very complex mission and an adversarial mission.”

So while it has been acknowledged that the F-35 needs to be able to embody software and hardware changes fast, the path to actually realizing agile development has taken two years, according to Valpiani.

As to how pilots will adapt to the FoX Tablet, LeClair said that “They want this, and they want it yesterday,” noting the “tremendous support from combat aviators.” LeClair likened the tablet concept to an electronic flight bag, the electronic information management device that has replaced the paperwork previously used for flight management tasks. In this way, the FoX Tablet would likely include flight maps, operating manuals, and perhaps even aircraft diagnostic data, as well as a range of apps optimized for different missions or test programs.

The tablet could also allow data to be displayed differently than what an aircraft’s cockpit displays will allow. For instance, 3D situational awareness display rendering, where threats and other situational and navigational information are displayed in a spatially volumetric form, can provide a huge advantage for aircrews trying to survive in a very dynamic and hostile environment. Some of the latest aircraft have wide area displays and graphics capabilities to do this. As far as we know, the F-35, whose systems are based on nearly 20-year-old tech today, is not capable of being able to generate this type of visual interface. But a tablet could be able to without upgrading the entire cockpit and its backend computing systems that drive its visual interfaces.

After the FoX Tablet comes the FoX BoX, which should optimize its utility in the cockpit. This is being developed at NAWS China Lake, home to ongoing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet mission systems test work. It aims to use a cyber-secure chipset to run “high-level, AI-capable computer processors that will serve as an operating system to communicate to aircraft, allowing the FoX Tablet to function mainly as a visual interface for aircrew.“

Meanwhile, ground tests of the tablet will continue on the F-35, before moving to the F/A-18, F-16, and the F-22. A first test flight — aboard an as yet unconfirmed platform — should take place later this year.

It’s a program that could have a significant impact in the cockpits of a whole range of aircraft, and one that we will continue to watch with interest.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com