The Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne was the world’s most advanced attack helicopter in its heyday, sporting revolutionary features that were far ahead of their time. Unfortunately, the Cheyenne program never fully succeeded due to technical issues, program management shortfalls, changing procurement priorities, high cost, and a crash in 1969 that left a test pilot dead. Despite never entering service, the Cheyenne left a profound impact on the concept of close air support and attack helicopter design, and today holds a special place in military aviation history. Looking back, one of its wildest features was a gunner’s seat that literally swiveled 360 degrees along with its weapons. Over half a century after appearing on the AH-56, that gunner’s station looks like something straight out of a Star Wars space battle sequence.

The need for a U.S. Army attack helicopter presented itself quickly when the United States entered the Vietnam War, although the Army’s search for a close air support and/or attack helicopter dates back to at least 1957. When the U.S. Army deployed the 57th Medical Detachment to Vietnam in March 1962, it sent along Bell UH-1 Iroquois, better known as “Hueys.” Large numbers of additional Hueys followed as more divisions were deployed to Vietnam. Many of these Hueys in Vietnam were subsequently armed, including with improvised weapon systems crafted by troops in the field. By the late 1960s, the U.S. Army was testing a wide variety of weapons on the Huey, including various automatic weapons, anti-tank guided missiles, and rocket launchers.

After seeing the clear need for a well-armed multi-mission attack helicopter for its involvement in the worsening Vietnam War, the U.S. Army established the Advanced Aerial Fire Support System (AAFSS) in 1964 to develop and procure a new attack helicopter. In 1965, the service declared Lockheed as the winner of the AAFSS program contract, and 10 prototypes of their proposed attack helicopter were ordered. The Army designated the helicopter the AH-56A and nicknamed it the Cheyenne.

The Cheyenne sported aerodynamic features not seen on other helicopters of its time. A nearly 4,000-horsepower turbine engine and a pusher propeller on the tail boom allowed the helicopter to hit a 224-mile-per-hour cruise speed and dash at speeds up to 240 miles per hour. The Cheyenne had 26.7-foot fixed wings to supply lift, which, combined with the pusher propeller, took much of the aerodynamic load off of its rigid main rotor. Supplying thrust with the pusher propeller meant that, unlike standard helicopters, the Cheyenne could quickly accelerate and decelerate without pitching its nose up or down. Conversely, the Cheyenne could also pitch its nose up or down while hovering without moving forward or backward.

Bob Mitchell, the curator of the U.S. Army Aviation Museum, says that this combination of aerodynamic features gave the Cheyenne a key advantage over other attack helicopters at the time. “One of the key factors in gunship operations – certainly when conducting diving fire – is that your speed builds exponentially, so you only have a couple of seconds to acquire, engage then start your recovery,” Mitchell said in an interview for an official Army story on the AH-56 in 2018. “On the Cheyenne, the pilot could enter his dive, then reverse thrust on the pusher to slow the aircraft down considerably, allowing him to fixate on the target, fire and then start his recovery. For that reason alone it was a beautiful gunship.”

The Cheyenne’s unique ability to distribute fire during its attack runs didn’t stop there.

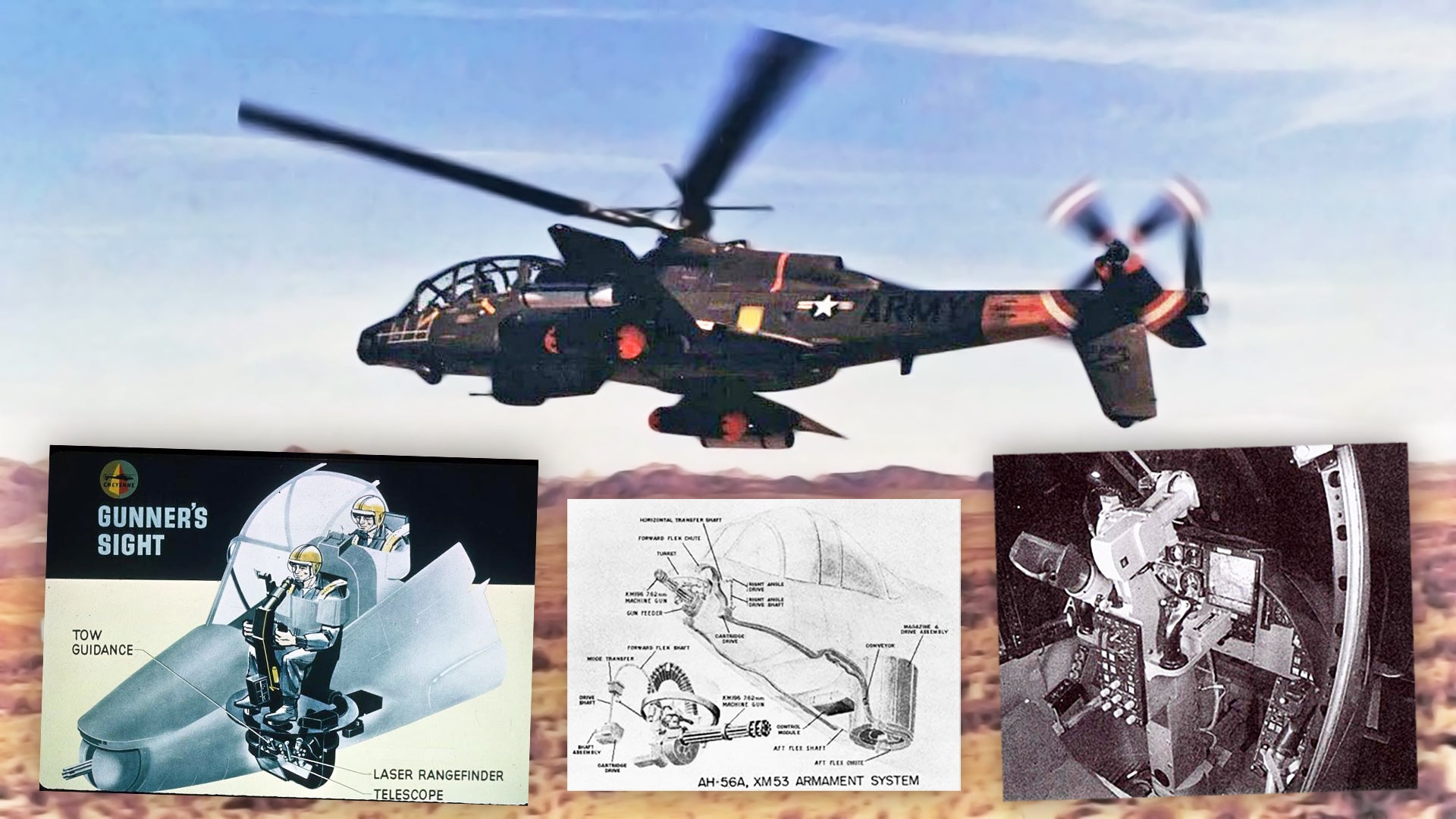

The Cheyenne had a two-seat tandem cockpit with the pilot in the rear and an advanced fire control suite for the gunner in the front seat. One of the craziest features of the Cheyenne was this gunner’s seat and control station.

Reminiscent of the gun turrets on World War II bombers, and like the swiveling gunner seats in the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars, the Cheyenne’s gunner’s seat, sighting system, and firing controls rotated a full 360 degrees to allow the gunner to face the direction in which he was firing, even completely to the rear.

A periscope sight allowed the gunner to aim the 30mm XM140 cannon in the belly turret with 360-degree direct fire capability. This drastically expanded what a potential attack run could look like for a helicopter of the era and increased the tactical flexibility of the helicopter overall.

The pilot wore a then-cutting-edge helmet-mounted display (HMD) that would also allow them to independently aim the helicopter’s nose-mounted turret. This forward turret could accommodate either a 7.62mm Minigun or a 40mm M129 grenade launcher.

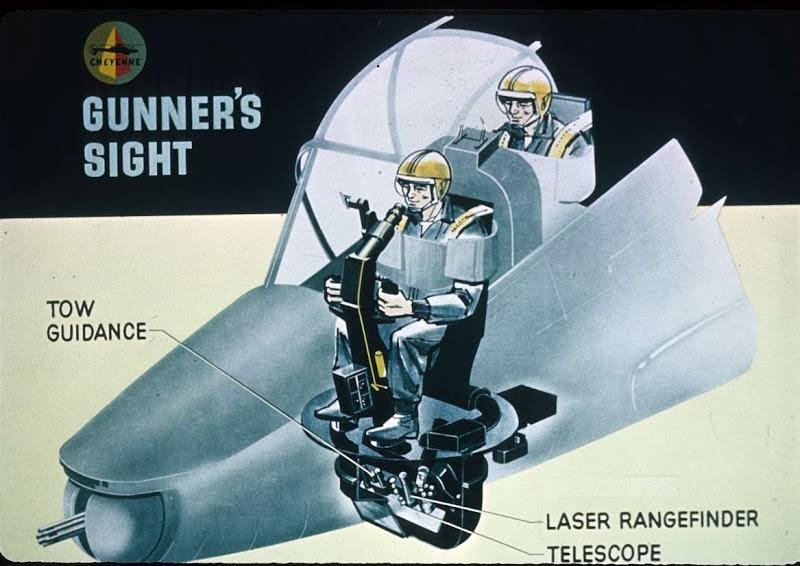

In addition to the turrets, the Cheyenne featured six hardpoints on its stub wings on which it could carry pods loaded with 2.75-inch rockets, wire-guided BGM-71 TOW antitank missiles, or external fuel tanks, among other stores. The Cheyenne’s fire control system featured doppler radar and a laser range finder, both well ahead of their time.

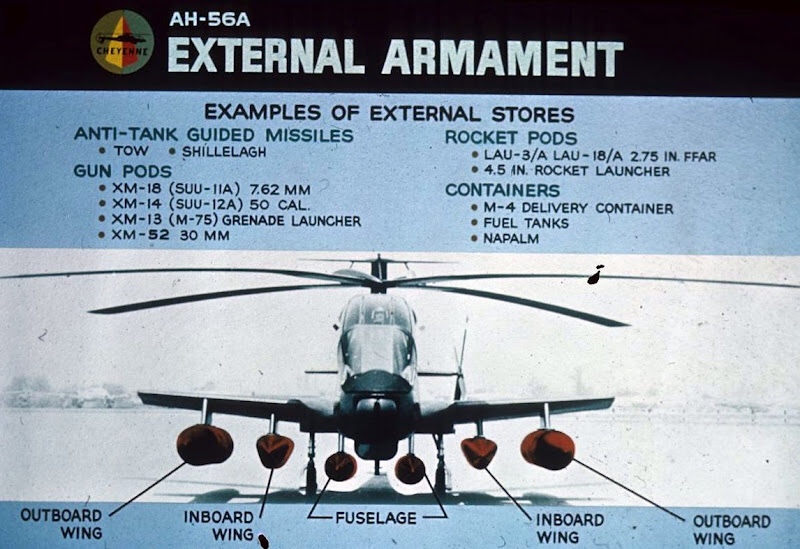

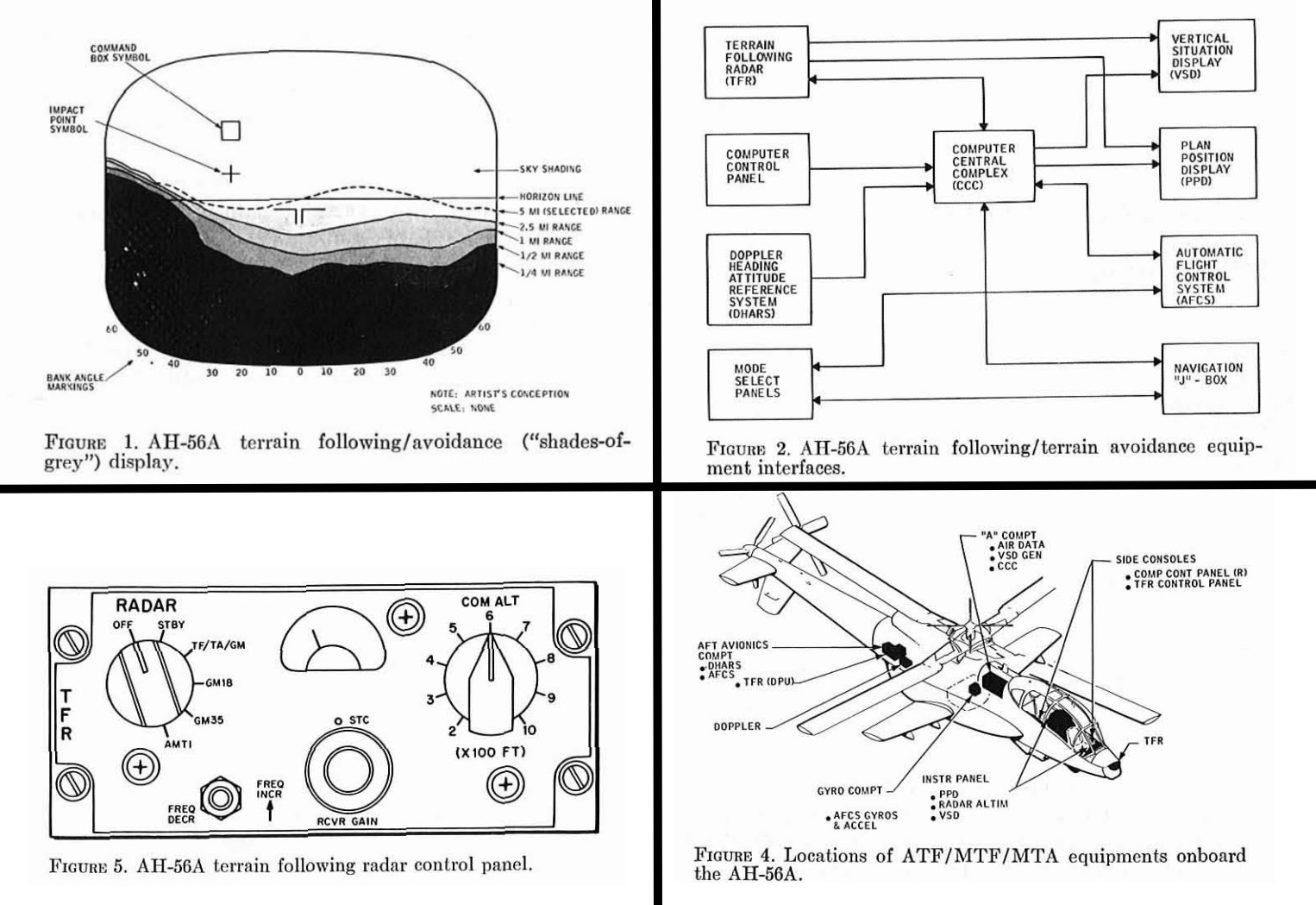

Many elements of the Cheyenne’s avionics systems were revolutionary, as well. The AH-56 sported an automatic flight control system and multiple radar systems, all connected to a then-state-of-the-art digital “Computer Central Complex” (CCC), allowing it to safely operate at low altitudes. Central to this was the Cheyenne’s AN/APQ-118 terrain-following radar system, manufactured by Norden, which could be used in both manual terrain-following (MTF) and automatic terrain-following (ATF) modes.

According to a 1971 study of the Cheyenne’s radar system published in the Journal of the American Helicopter Society, the computing suite in the AH-56 combined what were then cutting-edge avionics, including a forward-looking radar (terrain-following radar, or TFR), an automatic flight control system (AFCS), a vertical situation display (VSD), and a plan position display (PPD), enabling “safe, low altitude penetration of territories under IFR and night conditions.” Other sensor capabilities, including infrared and electronic support measures, as well as datalink systems, could help the unique helicopter act in an advanced scout and forward fire support director role.

The Cheyenne entered flight testing in 1967, including an initial test at Van Nuys Airport in which the Cheyenne wowed onlookers with its ability to “bow” to the crowd, that is, lowering its nose while in a stationary hover. Testing continued until March 1969, when the third Cheyenne prototype experienced unexpected vibration of its main rotor during a flight test. The vibrations caused the rotor to strike the canopy and tail boom of the aircraft, killing pilot David A. Beil instantly. In the aftermath of the crash, the Army immediately issued Lockheed a Cure Notice, a statement made by the government that a contractor has failed to meet its requirements. Two months later, the service’s Cheyenne production contract with Lockheed was terminated.

The Cheyenne program then languished in bureaucratic purgatory for several years until the Army officially canceled it in 1972. Not that long after, the Army launched the Advanced Attack Helicopter (AAH) program, which would eventually lead to the AH-64 Apache.

Official reasons for the AH-56’s cancellation were numerous, as we previously stated. However, according to the “Abridged History of Army Attack Helicopter Program” prepared by the Office of the Assistant Vice Chief of Staff of the Army (OAVCSA), there were numerous other problems related to the management of the program and not the helicopter itself, including the OAVCSA’s claim that Lockheed did not have “adequate helicopter experience.” Lockheed never pursued the development of another helicopter, although today’s Lockheed Martin Corporation develops helicopters through its Sikorsky subsidiary.

Another reason for the program’s demise was that the Cheyenne was designed at somewhat of a transitional period between analog and digital avionics. By the time the Army canceled the AH-56 program, digital avionics, which were lighter, faster, more reliable, more precise, and had better night and all-weather capabilities, were beginning to be developed. The cost of transitioning the AH-56 over to these new systems was also cited as a factor in its cancellation. The far simpler Bell Cobra, which was developed adjacent to Cheyenne as a low-risk alternative, was seen as a far cheaper and readily available option, in part due to it sharing an engine, transmission, and rotor system with variants of the Bell UH-1 Iroquois already in service.

Out of the 10 AH-56 prototypes that Lockheed built, four aircraft survive to this day: two are on display at the Army Aviation Museum at Fort Rucker in Alabama, one is at Fort Polk in Louisiana, and another at Kentucky’s Fort Campbell.

Many of the features found on the Cheyenne would later show up on other aircraft. For instance, by the time the Boeing AH-64 Apache entered service in 1986, helmet-mounted targeting displays were standard, although with far more capabilities than Cheyenne’s system had. The Apache also integrated the digital sensor and cockpit technologies that the AH-56 was just too early to incorporate.

As for swiveling gunner’s seats and sighting systems, just making the sensors themselves swivel, as well as the gun turret, and projecting the video feed in front of the pilot’s eye and on cockpit screens was a far more attractive option that was largely made possible by technological progress during the 1970s.

While the Cheyenne never officially entered service, it nevertheless had a profound impact on the design of future attack helicopters and helped unlock the possibilities of an advanced close air support aircraft concept. In his 2018 interview, U.S. Army Aviation Museum curator Bob Mitchell said that without the Cheyenne, there would be no A-10.

“I like to refer to the Cheyenne as the father of the A-10 program, because after that, the next aircraft the Air Force would design would be the A-10 Thunderbolt for close air support,” he explained. “Now, because of the Cheyenne, we finally got a dedicated aircraft for close air support.”

In addition, the Cheyenne’s high-speed, compound helicopter configuration has been reborn, at least to a certain degree, in the form of the Sikorsky S-97 Raider, a variant of which could very well become the Army’s next scout helicopter. Other variants of Sikorsky’s X-2 technology, namely the SB-1 Defiant, which is in the running to satisfy a huge component of the Army’s Future Vertical Lift program, also have some general similarities to AH-56. Even Boeing recently was looking to pitch a major refresh of their Apache by adding a pusher propeller and stub wings, which would have given it a very similar configuration to Cheyenne’s.

Maybe Cheyenne’s biggest problem was that it was too ambitious, and it definitely pioneered its share of wacky technological dead-ends, like the gunner’s rotating seat, but it also got an amazing amount right and should be remembered in that light.

Contact the author: Brett@TheDrive.com